Macrophytes in Drainage Ditches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps

Appendix 11.5.1: Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps These distribution maps are for 116 aquatic vascular macrophyte species (Table 1). Aquatic designation follows habitat descriptions in Haines and Vining (1998), and includes submergent, floating and some emergent species. See Appendix 11.4 for list of species. Also included in Appendix 11.4 is the number of HUC-10 watersheds from which each taxon has been recorded, and the county-level distributions. Data are from nine sources, as compiled in the MABP database (plus a few additional records derived from ancilliary information contained in reports from two fisheries surveys in the Upper St. John basin organized by The Nature Conservancy). With the exception of the University of Maine herbarium records, most locations represent point samples (coordinates were provided in data sources or derived by MABP from site descriptions in data sources). The herbarium data are identified only to township. In the species distribution maps, town-level records are indicated by center-points (centroids). Figure 1 on this page shows as polygons the towns where taxon records are identified only at the town level. Data Sources: MABP ID MABP DataSet Name Provider 7 Rare taxa from MNAP lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 8 Lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 35 Acadia National Park plant survey C. Greene et al. 63 Lake plant surveys A. Dieffenbacher-Krall 71 Natural Heritage Database (rare plants) MNAP 91 University of Maine herbarium database C. Campbell 183 Natural Heritage Database (delisted species) MNAP 194 Rapid bioassessment surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 207 Invasive aquatic plant records MDEP Maps are in alphabetical order by species name. -

Download the Full Report Pdf, 2.9 MB

VKM Report 2016:50 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety Report from the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 2016:50 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety 01.11.2016 ISBN: 00000-00000 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) Po 4404 Nydalen N – 0403 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] www.vkm.no www.english.vkm.no Suggested citation: VKM (2016). Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants. Scientific Opinion on the on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety ISBN: 978-82-8259-240-6, Oslo, Norway. VKM Report 2016:50 Title: Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Authors preparing the draft opinion Hugo de Boer (chair), Maria G. Asmyhr (VKM staff), Hanne H. Grundt, Inga Kjersti Sjøtun, Hans K. Stenøien, Iris Stiers. Assessed and approved The opinion has been assessed and approved by Panel on Alien organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Members of the panel are: Vigdis Vandvik (chair), Hugo de Boer, Jan Ove Gjershaug, Kjetil Hindar, Lawrence Kirkendall, Nina Elisabeth Nagy, Anders Nielsen, Eli K. -

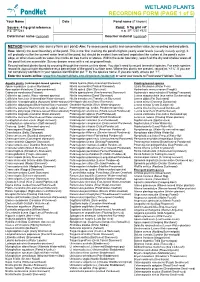

WETLAND PLANTS – Full Species List (English) RECORDING FORM

WETLAND PLANTS – full species list (English) RECORDING FORM Surveyor Name(s) Pond name Date e.g. John Smith (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 (see your map) e.g. SP 1235 4325 (see your map) METHOD: wetland plants (full species list) survey Survey a single Focal Pond in each 1km square Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value using plants, by recording all wetland plant species present within the pond’s outer boundary. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from the extent of wetland vegetation (for example a ring of rushes growing at the pond’s outer edge), or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. After your survey please enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed , non-native sp. -

NJ Native Plants - USDA

NJ Native Plants - USDA Scientific Name Common Name N/I Family Category National Wetland Indicator Status Thermopsis villosa Aaron's rod N Fabaceae Dicot Rubus depavitus Aberdeen dewberry N Rosaceae Dicot Artemisia absinthium absinthium I Asteraceae Dicot Aplectrum hyemale Adam and Eve N Orchidaceae Monocot FAC-, FACW Yucca filamentosa Adam's needle N Agavaceae Monocot Gentianella quinquefolia agueweed N Gentianaceae Dicot FAC, FACW- Rhamnus alnifolia alderleaf buckthorn N Rhamnaceae Dicot FACU, OBL Medicago sativa alfalfa I Fabaceae Dicot Ranunculus cymbalaria alkali buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot OBL Rubus allegheniensis Allegheny blackberry N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, FACW Hieracium paniculatum Allegheny hawkweed N Asteraceae Dicot Mimulus ringens Allegheny monkeyflower N Scrophulariaceae Dicot OBL Ranunculus allegheniensis Allegheny Mountain buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot FACU, FAC Prunus alleghaniensis Allegheny plum N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, NI Amelanchier laevis Allegheny serviceberry N Rosaceae Dicot Hylotelephium telephioides Allegheny stonecrop N Crassulaceae Dicot Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine N Fumariaceae Dicot Centaurea transalpina alpine knapweed N Asteraceae Dicot Potamogeton alpinus alpine pondweed N Potamogetonaceae Monocot OBL Viola labradorica alpine violet N Violaceae Dicot FAC Trifolium hybridum alsike clover I Fabaceae Dicot FACU-, FAC Cornus alternifolia alternateleaf dogwood N Cornaceae Dicot Strophostyles helvola amberique-bean N Fabaceae Dicot Puccinellia americana American alkaligrass N Poaceae Monocot Heuchera americana -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Floristic Account of Submersed Aquatic Angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, Northwestern Pakistan

Penfound WT. 1940. The biology of Dianthera americana L. Am. Midl. Nat. Touchette BW, Frank A. 2009. Xylem potential- and water content-break- 24:242-247. points in two wetland forbs: indicators of drought resistance in emergent Qui D, Wu Z, Liu B, Deng J, Fu G, He F. 2001. The restoration of aquatic mac- hydrophytes. Aquat. Biol. 6:67-75. rophytes for improving water quality in a hypertrophic shallow lake in Touchette BW, Iannacone LR, Turner G, Frank A. 2007. Drought tolerance Hubei Province, China. Ecol. Eng. 18:147-156. versus drought avoidance: A comparison of plant-water relations in her- Schaff SD, Pezeshki SR, Shields FD. 2003. Effects of soil conditions on sur- baceous wetland plants subjected to water withdrawal and repletion. Wet- vival and growth of black willow cuttings. Environ. Manage. 31:748-763. lands. 27:656-667. Strakosh TR, Eitzmann JL, Gido KB, Guy CS. 2005. The response of water wil- low Justicia americana to different water inundation and desiccation regimes. N. Am. J. Fish. Manage. 25:1476-1485. J. Aquat. Plant Manage. 49: 125-128 Floristic account of submersed aquatic angiosperms of Dera Ismail Khan District, northwestern Pakistan SARFARAZ KHAN MARWAT, MIR AJAB KHAN, MUSHTAQ AHMAD AND MUHAMMAD ZAFAR* INTRODUCTION and root (Lancar and Krake 2002). The aquatic plants are of various types, some emergent and rooted on the bottom and Pakistan is a developing country of South Asia covering an others submerged. Still others are free-floating, and some area of 87.98 million ha (217 million ac), located 23-37°N 61- are rooted on the bank of the impoundments, adopting 76°E, with diverse geological and climatic environments. -

Pondnet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5)

WETLAND PLANTS PondNet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5) Your Name Date Pond name (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 e.g. SP 1235 4325 Determiner name (optional) Voucher material (optional) METHOD (complete one survey form per pond) Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value, by recording wetland plants. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from wetland vegetation like rushes at the pond’s outer edge, or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put ’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. Enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ or send your results to Freshwater Habitats Trust. Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Nitella hyalina (Many-branched Stonewort) Floating-leaved species Apium inundatum (Lesser Marshwort) Nitella mucronata (Pointed Stonewort) Azolla filiculoides (Water Fern) Aponogeton distachyos (Cape-pondweed) Nitella opaca (Dark Stonewort) Hydrocharis morsus-ranae (Frogbit) Cabomba caroliniana (Fanwort) Nitella spanioclema (Few-branched Stonewort) Hydrocotyle ranunculoides (Floating Pennywort) Callitriche sp. -

Buglife Ditches Report Vol1

The ecological status of ditch systems An investigation into the current status of the aquatic invertebrate and plant communities of grazing marsh ditch systems in England and Wales Technical Report Volume 1 Summary of methods and major findings C.M. Drake N.F Stewart M.A. Palmer V.L. Kindemba September 2010 Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust 1 Little whirlpool ram’s-horn snail ( Anisus vorticulus ) © Roger Key This report should be cited as: Drake, C.M, Stewart, N.F., Palmer, M.A. & Kindemba, V. L. (2010) The ecological status of ditch systems: an investigation into the current status of the aquatic invertebrate and plant communities of grazing marsh ditch systems in England and Wales. Technical Report. Buglife – The Invertebrate Conservation Trust, Peterborough. ISBN: 1-904878-98-8 2 Contents Volume 1 Acknowledgements 5 Executive summary 6 1 Introduction 8 1.1 The national context 8 1.2 Previous relevant studies 8 1.3 The core project 9 1.4 Companion projects 10 2 Overview of methods 12 2.1 Site selection 12 2.2 Survey coverage 14 2.3 Field survey methods 17 2.4 Data storage 17 2.5 Classification and evaluation techniques 19 2.6 Repeat sampling of ditches in Somerset 19 2.7 Investigation of change over time 20 3 Botanical classification of ditches 21 3.1 Methods 21 3.2 Results 22 3.3 Explanatory environmental variables and vegetation characteristics 26 3.4 Comparison with previous ditch vegetation classifications 30 3.5 Affinities with the National Vegetation Classification 32 Botanical classification of ditches: key points -

Alien Water Lettuce (Pistia Stratiotes L.) Outcompeted Native Macrophytes and Altered the Ecological Conditions of a Sava Oxbow Lake (SE Slovenia)

Acta Bot. Croat. 79 (1), 35–42, 2020 CODEN: ABCRA 25 DOI: 10.37427/botcro-2020-009 ISSN 0365-0588 eISSN 1847-8476 Alien water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes L.) outcompeted native macrophytes and altered the ecological conditions of a Sava oxbow lake (SE Slovenia) Martina Jaklič1, Špela Koren2, Nejc Jogan3* 1University Medical Centre, Zaloska 2, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 2Institute for Water of the Republic of Slovenia, Einspielerjeva ulica 6, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia 3University of Ljubljana, Biotechnical Faculty, Department of Biology, Večna pot 111, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia Abstract – Introduction of an invasive alien macrophyte water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes L.) radically changed the oxbow lake in Prilipe (SE Slovenia) which has thermal springs that enables the winter survival of this tropical in- vader. About 10 years after the first record ofP . stratiotes, the number, abundance and biomass of indigenous and non-indigenous macrophytes as well as different abiotic parameters were measured. In that period, colonized sections (~94% of the oxbow lake) were completely covered with water lettuce, and the only reservoirs of indige- nous macrophyte species were the non-colonized areas (6%). Research in 2011 found only a third of the previ- ously recorded indigenous macrophytes, but then only in small section without P. stratiotes. Three of the species that disappeared were on the Red data list. In the colonized section a higher biomass was observed than in the non-colonized section because of high abundance of water lettuce which remained the only macrophyte. Due to the presence of P. stratiotes, the intensity of light penetrating into the depth and water circulation were reduced, as was the oxygen saturation of the water. -

Wetland Plants Survey Form

WETLAND PLANTS PondNet RECORDING FORM (PAGE 1 of 5) Your Name Date Pond name (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 e.g. SP 1235 4325 Determiner name (optional) Voucher material (optional) METHOD (complete one survey form per pond) Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value, by recording wetland plants. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from wetland vegetation like rushes at the pond’s outer edge, or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. Enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ or send your results to Freshwater Habitats Trust. Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bearded (Chara canescens) Floating-leaved species Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Awlwort (Subularia aquatica) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed, non-native sp. -

(Egeria Densa Planch.) Invasion Reaches Southeast Europe

BioInvasions Records (2018) Volume 7, Issue 4: 381–389 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.4.05 © 2018 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2018 REABIC This paper is published under terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (Attribution 4.0 International - CC BY 4.0) Research Article The Brazilian elodea (Egeria densa Planch.) invasion reaches Southeast Europe Anja Rimac1, Igor Stanković2, Antun Alegro1,*, Sanja Gottstein3, Nikola Koletić1, Nina Vuković1, Vedran Šegota1 and Antonija Žižić-Nakić2 1Division of Botany, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Marulićev trg 20/II, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 2Hrvatske vode, Central Water Management Laboratory, Ulica grada Vukovara 220, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3Division of Zoology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Zagreb, Rooseveltov trg 6, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia Author e-mails: [email protected] (AR), [email protected] (IS), [email protected] (AA), [email protected] (SG), [email protected] (VŠ), [email protected] (NK), [email protected] (AZ) *Corresponding author Received: 12 April 2018 / Accepted: 1 August 2018 / Published online: 15 October 2018 Handling editor: Carla Lambertini Abstract Egeria densa is a South American aquatic plant species considered highly invasive outside of its original range, especially in temperate and warm climates and artificially heated waters in colder regions. We report the first occurrence and the spread of E. densa in Southeast Europe, along with physicochemical and phytosociological characteristics of its habitats. Flowering male populations were observed and monitored in limnocrene springs and rivers in the Mediterranean part of Croatia from 2013 to 2017.