Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

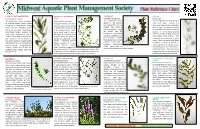

Red Names=Invasive Species Green Names=Native Species

CURLY-LEAF PONDWEED EURASIAN WATERMIL- FANWORT CHARA (Potamogeton crispus) FOIL (Cabomba caroliniana) (Chara spp.) This undesirable exotic, also known (Myriophyllum spicatum) This submerged exotic Chara is typically found growing in species is not common as Crisp Pondweed, bears a waxy An aggressive plant, this exotic clear, hard water. Lacking true but management tools are cuticle on its upper leaves making milfoil can grow nearly 10 feet stems and leaves, Chara is actually a limited. Very similar to them stiff and somewhat brittle. in length forming dense mats form of algae. It’s stems are hollow aquarium species. Leaves The leaves have been described as at the waters surface. Grow- with leaf-like structures in a whorled are divided into fine resembling lasagna noodles, but ing in muck, sand, or rock, it pattern. It may be found growing branches in a fan-like ap- upon close inspection a row of has become a nuisance plant with tiny, orange fruiting bodies on pearance, opposite struc- “teeth” can be seen to line the mar- in many lakes and ponds by the branches called akinetes. Thick ture, spanning 2 inches. gins. Growing in dense mats near quickly outcompeting native masses of Chara can form in some Floating leaves are small, the water’s surface, it outcompetes species. Identifying features areas. Often confused with Starry diamond shape with a native plants for sun and space very include a pattern of 4 leaves stonewort, Coontail or Milfoils, it emergent white/pinkish early in spring. By midsummer, whorled around a hollow can be identified by a gritty texture flower. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

(BCF), Translocation Factor (TF) and Metal Enrichment Factor (MEF) Abilities of Aquatic Macrophyte Species Exposed to Metal Contaminated Wastewater

ISSN(Online): 2319-8753 ISSN (Print): 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (A High Impact Factor, Monthly, Peer Reviewed Journal) Visit: www.ijirset.com Vol. 8, Issue 1, January 2019 Evaluation of Bioaccumulation Factor (BAF), Bioconcentration Factor (BCF), Translocation Factor (TF) and Metal Enrichment Factor (MEF) Abilities of Aquatic Macrophyte Species Exposed to Metal Contaminated Wastewater S. S. Shingadgaon1, B.L. Chavan2 Research Scholar, Department of Environmental Science, School of Earth Sciences, Solapur University, Solapur, MS, India1 Former Professor and Head, Department of Environmental Science, Solapur University Solapur and presently working at Department of Environmental Science, Dr.Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University, Aurangabad, MS, India 2 ABSTRACT: Wastewaters receiving aquatic bodies are quiet complex in terms of pollutants, the transport and interactions with heavy metals. This complexity is primarily due to high variability of pollutants, contaminants and related parameters. The macrophytes are plausible bio-indicators of the pollution load and level of metals within the aquatic systems than the wastewater or sediment analyses. The potential ability of aquatic macrophytes in natural water bodies receiving municipal sewage from Solapur city was assessed. Data from the studies on macrophytes exposed to a mixed test bath of metals and examined to know their potentialities to accumulate heavy metals for judging their suitability for phytoremediation technology -

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

(Potamogetonaceae), Según Las Categorías Uicn-2001

Flora Montiberica 39: 37-46 (VI-2008). ISSN 1138-5952 RECATALOGACIÓN DE POTAMOGETON PRAELONGUS WULFEN (POTAMOGETONACEAE), SEGÚN LAS CATEGORÍAS UICN-2001 José Luis BENITO ALONSO*, Esperança GACIA**, Enric BALLESTEROS**, Eglantine CHAPPUIS** & Empar CARRILLO*** *Jolube Consultoría Ambiental. Jaca (Huesca) [email protected] - www.jolube.net **Centre d'Estudis Avançats de Blanes, CSIC - www.ceab.csic.es ***Departamento de Biología Vegetal. Facultad de Biología. Universidad de Barcelona - www.bio.ub.es RESUMEN: Proponemos la recatalogación de la espiga de agua Potamogeton praelongus Wulfen, a la categoría de «En Peligro Crítico (CR)» según criterios UICN-2001, así como su inclusión en los catálogos oficiales de especies amenazadas de España, Aragón y Cataluña en la categorías de «En peligro de extinción». Pa- labras clave: Vegetación hidrofítica, macrófitos acuáticos, Potamion, fitosociología, flora amenazada, categorías UICN 2001, análisis de agua, Pirineos, Aragón, Catalu- ña, España. SUMMARY: We propose to recatalogue Potamogeton praelongus Wulfen, into the category of «Critically Endangered (CR)» according to IUCN-2001 criteria, and its inclusion in the official catalogue of threatened species of Spain, Aragon and Ca- talonia in the categories of «Danger Extinction». Keywords: Hydrophytic vegetation, aquatic macrophytes, Potamion, phytosociology, threatened flora, IUCN 2001 categories, water analysis, Pyrenees, Aragon, Catalonia, Spain. INTRODUCCIÓN y funcionamiento de comunidades de ma- crófitos de lagos de alta montaña» (GA- La espiga -

Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps

Appendix 11.5.1: Aquatic Vascular Plant Species Distribution Maps These distribution maps are for 116 aquatic vascular macrophyte species (Table 1). Aquatic designation follows habitat descriptions in Haines and Vining (1998), and includes submergent, floating and some emergent species. See Appendix 11.4 for list of species. Also included in Appendix 11.4 is the number of HUC-10 watersheds from which each taxon has been recorded, and the county-level distributions. Data are from nine sources, as compiled in the MABP database (plus a few additional records derived from ancilliary information contained in reports from two fisheries surveys in the Upper St. John basin organized by The Nature Conservancy). With the exception of the University of Maine herbarium records, most locations represent point samples (coordinates were provided in data sources or derived by MABP from site descriptions in data sources). The herbarium data are identified only to township. In the species distribution maps, town-level records are indicated by center-points (centroids). Figure 1 on this page shows as polygons the towns where taxon records are identified only at the town level. Data Sources: MABP ID MABP DataSet Name Provider 7 Rare taxa from MNAP lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 8 Lake plant surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 35 Acadia National Park plant survey C. Greene et al. 63 Lake plant surveys A. Dieffenbacher-Krall 71 Natural Heritage Database (rare plants) MNAP 91 University of Maine herbarium database C. Campbell 183 Natural Heritage Database (delisted species) MNAP 194 Rapid bioassessment surveys D. Cameron, MNAP 207 Invasive aquatic plant records MDEP Maps are in alphabetical order by species name. -

![Vascular Plants of Williamson County Potamogeton Nodosus − LONGLEAF PONDWEED [Potamogetonaceae]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5932/vascular-plants-of-williamson-county-potamogeton-nodosus-longleaf-pondweed-potamogetonaceae-455932.webp)

Vascular Plants of Williamson County Potamogeton Nodosus − LONGLEAF PONDWEED [Potamogetonaceae]

Vascular Plants of Williamson County Potamogeton nodosus − LONGLEAF PONDWEED [Potamogetonaceae] Potamogeton nodosus Poiret, LONGLEAF PONDWEED. Aquatic perennial herb, clonal, rhizomatous, fibrous-rooted, not rosetted, mostly submersed with floating leaves; shoots with only cauline leaves with long petioles and stems and rhizomes with long internodes, glabrous; rhizomes cylindric, internodes to 190 × 3 mm, white; adventitious roots nodal, slender. Stems: ± cylindric, to 210 × 3 mm, white to green lacking purple spots; with elongate air canals in “cortex” (aerenchyma). Leaves: alternate distichous, simple, petiolate, with stipules; stipule 1, attached across node, V-folded along midvein, 35−65 mm long, translucent with many parallel veins; of submersed leaf petiole ± hemicylindric with rounded edges, 40−105 mm long, with aerenchyma, blade linear-oblanceolate to narrowly elliptic to narrowly oblanceolate, 18−53 × 6−9 mm, long-tapered at base, entire, blunt acute at tip lacking fine point at tip, midrib giving rise to 8 ascending, parallel lateral veins, midrib slightly raised on both surfaces; of floating leaf petiole ± hemicylindric with rounded edges, 20−210 mm long, with aerenchyma, blade elliptic, 28−95 × 20−37 mm, tapered at base, entire, broadly acute to obtuse or rounded at tip, midrib giving rise to 20 ascending, parallel lateral veins with veins slightly raised on lower surface, upper surface flat, water repellent, and many stomates, lower surface wettable and lacking stomates. Inflorescence: spike, axillary, emergent at anthesis, -

Download the Full Report Pdf, 2.9 MB

VKM Report 2016:50 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety Report from the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) 2016:50 Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Opinion of the Panel on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety 01.11.2016 ISBN: 00000-00000 Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety (VKM) Po 4404 Nydalen N – 0403 Oslo Norway Phone: +47 21 62 28 00 Email: [email protected] www.vkm.no www.english.vkm.no Suggested citation: VKM (2016). Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants. Scientific Opinion on the on Alien Organisms and Trade in Endangered species of the Norwegian Scientific Committee for Food Safety ISBN: 978-82-8259-240-6, Oslo, Norway. VKM Report 2016:50 Title: Assessment of the risks to Norwegian biodiversity from the import and keeping of aquarium and garden pond plants Authors preparing the draft opinion Hugo de Boer (chair), Maria G. Asmyhr (VKM staff), Hanne H. Grundt, Inga Kjersti Sjøtun, Hans K. Stenøien, Iris Stiers. Assessed and approved The opinion has been assessed and approved by Panel on Alien organisms and Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Members of the panel are: Vigdis Vandvik (chair), Hugo de Boer, Jan Ove Gjershaug, Kjetil Hindar, Lawrence Kirkendall, Nina Elisabeth Nagy, Anders Nielsen, Eli K. -

LACON: Lake Assessment for Conservation Version 1 Manual

Scottish Natural Heritage Archive Report No. 175 LACON: Lake Assessment for Conservation Version 1 Manual ARCHIVE REPORT Archive Report No. 175 LACON: Lake Assessment for Conservation Version 1 Manual For further information on this report please contact: Alison Lee Scottish Natural Heritage Silvan House 231 Corstorphine Road EDINBURGH EH12 7AT Telephone: 0131 316 2620 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Palmer, M.A. 2008. LACON: Lake Assessment for Conservation – Version 1 Manual. Scottish Natural Heritage Archive Report No. 175. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2019. Archive Reports Scottish Natural Heritage is committed to making the findings of all of its research publicly available whenever possible. In the past, a number of reports from staff and contractors were produced as paper documents and lodged in the SNH library or file systems. Some related to Site Condition Monitoring, others covered a range of subjects. These were not published as Research Reports for a number of reasons. In order to make these reports more available, we have decided to publish them online under the series title of Archive Reports. These will be numbered consecutively in the order that they are prepared for web publication. Their publication date, authors and title will be recorded as presented in the original report. The Archive Reports will be published as scanned PDF files of the original reports. -

WETLAND PLANTS – Full Species List (English) RECORDING FORM

WETLAND PLANTS – full species list (English) RECORDING FORM Surveyor Name(s) Pond name Date e.g. John Smith (if known) Square: 4 fig grid reference Pond: 8 fig grid ref e.g. SP1243 (see your map) e.g. SP 1235 4325 (see your map) METHOD: wetland plants (full species list) survey Survey a single Focal Pond in each 1km square Aim: To assess pond quality and conservation value using plants, by recording all wetland plant species present within the pond’s outer boundary. How: Identify the outer boundary of the pond. This is the ‘line’ marking the pond’s highest yearly water levels (usually in early spring). It will probably not be the current water level of the pond, but should be evident from the extent of wetland vegetation (for example a ring of rushes growing at the pond’s outer edge), or other clues such as water-line marks on tree trunks or stones. Within the outer boundary, search all the dry and shallow areas of the pond that are accessible. Survey deeper areas with a net or grapnel hook. Record wetland plants found by crossing through the names on this sheet. You don’t need to record terrestrial species. For each species record its approximate abundance as a percentage of the pond’s surface area. Where few plants are present, record as ‘<1%’. If you are not completely confident in your species identification put’?’ by the species name. If you are really unsure put ‘??’. After your survey please enter the results online: www.freshwaterhabitats.org.uk/projects/waternet/ Aquatic plants (submerged-leaved species) Stonewort, Bristly (Chara hispida) Bistort, Amphibious (Persicaria amphibia) Arrowhead (Sagittaria sagittifolia) Stonewort, Clustered (Tolypella glomerata) Crystalwort, Channelled (Riccia canaliculata) Arrowhead, Canadian (Sagittaria rigida) Stonewort, Common (Chara vulgaris) Crystalwort, Lizard (Riccia bifurca) Arrowhead, Narrow-leaved (Sagittaria subulata) Stonewort, Convergent (Chara connivens) Duckweed , non-native sp. -

NJ Native Plants - USDA

NJ Native Plants - USDA Scientific Name Common Name N/I Family Category National Wetland Indicator Status Thermopsis villosa Aaron's rod N Fabaceae Dicot Rubus depavitus Aberdeen dewberry N Rosaceae Dicot Artemisia absinthium absinthium I Asteraceae Dicot Aplectrum hyemale Adam and Eve N Orchidaceae Monocot FAC-, FACW Yucca filamentosa Adam's needle N Agavaceae Monocot Gentianella quinquefolia agueweed N Gentianaceae Dicot FAC, FACW- Rhamnus alnifolia alderleaf buckthorn N Rhamnaceae Dicot FACU, OBL Medicago sativa alfalfa I Fabaceae Dicot Ranunculus cymbalaria alkali buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot OBL Rubus allegheniensis Allegheny blackberry N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, FACW Hieracium paniculatum Allegheny hawkweed N Asteraceae Dicot Mimulus ringens Allegheny monkeyflower N Scrophulariaceae Dicot OBL Ranunculus allegheniensis Allegheny Mountain buttercup N Ranunculaceae Dicot FACU, FAC Prunus alleghaniensis Allegheny plum N Rosaceae Dicot UPL, NI Amelanchier laevis Allegheny serviceberry N Rosaceae Dicot Hylotelephium telephioides Allegheny stonecrop N Crassulaceae Dicot Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine N Fumariaceae Dicot Centaurea transalpina alpine knapweed N Asteraceae Dicot Potamogeton alpinus alpine pondweed N Potamogetonaceae Monocot OBL Viola labradorica alpine violet N Violaceae Dicot FAC Trifolium hybridum alsike clover I Fabaceae Dicot FACU-, FAC Cornus alternifolia alternateleaf dogwood N Cornaceae Dicot Strophostyles helvola amberique-bean N Fabaceae Dicot Puccinellia americana American alkaligrass N Poaceae Monocot Heuchera americana