Growing the Game: the NWHL As a Microcosm Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Weekly Release

Pete Souris Assistant Commissioner WOMEN’S for Public Relations Hockey East Association WEEKLY 591 North Ave – #2 Wakefield, MA 01880 RELEASE Office: (781) 245-2122 Cell: (603) 512-1166 www.HockeyEastOnline.com [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: MONDAY, MARCH 7, 2011 WEEKLY RELEASE #21 BOSTON COLLEGE WINS FIRST WHEA CHAMPIONSHIP IN SCHOOL HISTORY ~ Eagles and Terriers host NCAA Tournament games on Saturday ~ PURE HOCKEY PLAYER OF THE WEEK RECENT RESULTS #16 KELLI STACK, BOSTON COLLEGE (Senior Forward; Brooklyn Heights, Ohio) Friday, February 18 No. 4 Boston U. 2 at Maine 0 * Stack captured tournament MVP honors; recorded one goal and tallied two assists in the two-game tournament over the weekend. She buried the overtime game-winning goal vs. Saturday, February 19 Providence in the semifinal victory on Saturday at Walter Brown at No. 9 Providence 3, Vermont 2 * Arena. at Maine 3, No. 4 Boston U. 2 (OT)* Connecticut 4 at Northeastern 2 * New Hampshire 0 at No. 7 Boston College 0 (OT) * PRO AMBITIONS ROOKIE OF THE WEEK Sunday, February 20 #4 MELISSA BIZZARI, BOSTON COLLEGE (Freshman Forward; Stowe, Vt.) at No. 9 Providence 6, Vermont 1* No. 7 Boston College 2 at New Hampshire 1* Bizzari tallied a team-high three points (1g,2a) in league tournament victories Northeastern 1 at Connecticut 1 (OT) * over Providence and Northeastern over the weekend at Walter Brown Arena to help the Eagles to their first WHEA title in school history. Saturday, February 26 WHEA Quarterfinals Northeastern 4 at Connecticut 0 at Providence 5, Maine 2 WHEA DEFENSIVE PLAYER OF THE WEEK Saturday, March 5 #41 FLORENCE SCHELLING, NORTHEASTERN (Jr. -

2015 US Women's National Team

2015 U.S. Women’s National Team Four Nations Cup • USA vs. CAN • Sat., Nov. 8, 2015 Energi Arena • Sundsvall, Sweden LEFT WING CENTER RIGHT WING Coyne, Kendall Decker, Brianna Knight, Hilary 26 14 21 5-2 • 125 Palos Heights, Ill. 5-4 • 148 Dousman, Wis. 5-11 • 172 Sun Valley, Idaho Left Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: 5/25/92 Northeastern University (HEA) 5/13/91 Boston Pride (NWHL) 7/12/89 Boston Pride (NWHL) 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 2-1--3 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 1-2--3 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 2-2--4 Darkangelo, Shiann Stack, Kelli Thunstrom, Allie 27 16 20 5-9 • 145 Brighton, Mich. 5-5 • 136 Brooklyn Heights, Ohio 5-5 • 145 Mablewood, Minn. Left Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: 11/28/93 Connecticut Whale (NWHL) 1/13/88 Connecticut Whale (NWHL) 4/20/88 Minnesota Whitecaps (WWHL) 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 0-1--1 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 2-5--7 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP 1-0--1 Anderson, Stephanie Lamoureux, Jocelyne Pelkey, Amanda 18 17 11 5-9 • 165 North St. Paul, Minn. 5-6 • 155 Grand Forks, N.D. 5-3 • 130 Montpelier, Vt. Left Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: Right Shot Current Team: 11/27/92 Bemidji State University (WCHA) 7/3/89 Minnesota Whitecaps (WWHL) 5/29/93 Boston Pride (NWHL) 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 0-1--1 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 4-1--5 2015 Four Nations: 3 GP, 0-0--0 Norby, Presley Duggan, Meghan - C Hickel, Zoe 28 10 36 5-5 • 129 Shorewood, Minn. -

2010-11 WCHA Men's Season-In-Review

Western Collegiate Hockey Association Bruce M. McLeod Commissioner Carol LaBelle-Ehrhardt Assistant Commissioner of Operations Greg Shepherd Supervisor of Officials Administrative Office April 25, 2011 Western Collegiate Hockey Association 2211 S. Josephine Street, Room 302 Denver, CO 80210 2010-11 WCHA Men’s Season-in-Review p: 303 871-4491. f: 303 871-4770 email: [email protected] Minnesota Duluth Reigns as 2011 National Champions as WCHA Doug Spencer Marks Record 37th NCAA Men’s Team Title Since 1951 Associate Commissioner for Public Relations Bulldogs Capture Program’s First National Championship with Wins Over Notre Dame & Michigan Public Relations Office April 7 & 9 at Xcel Energy Center in Saint Paul; WCHA Now Owns Record 37 NCAA Div. 1 Titles Western Collegiate Hockey Association 559 D’Onofrio Drive, Ste. 103 Since 1951; North Dakota Claims WCHA Regular Season Championship and MacNaughton Cup; Madison, WI 53719-2096 Sioux Earn 2011 Red Baron WCHA Final Five Playoff Title, Broadmoor Trophy; North Dakota, p: 608 829-0100. f: 608 829-0200 Denver, Minnesota Duluth, Nebraska Omaha, Colorado College Earn NCAA Tournament Berths; email: [email protected] Sioux are NCAA Midwest Regional Champs, Bulldogs Earn NCAA East Regional Crown; Seven Home of a Record 36 Men’s WCHA Players Earn All-American Honors; Final 2010-11 Div. 1 Men’s National Polls Have UMD National Championship No. 1, UND No. 2/3, DU No. 7, CC No. 11, UNO No. 14; WCHA Teams Go 56-27-12 (.653) in Div. 1 Teams Since 1951 Non-Conference Play 1952, 1953, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1964, SAINT PAUL, Minn. -

Wcha Alumni Ready for 2016-17 Professional

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WCHA ALUMNI READY FOR 2016-17 PROFESSIONAL CAMPAIGN Three dozen former Association players, representing all eight member institutions, to play for NWHC, CWHL and Minnesota Whitecaps EDINA, Minn. – Oct. 3, 2016 – Three dozen former Western Collegiate Hockey Association (WCHA) Women’s League players will start the season on the rosters of the two professional women’s hockey leagues this season. Eighteen WCHA alumni are spending the 2016-17 season playing in the National Women's Hockey League (NWHL), while 18 former Association players are competing in the Canadian Women's Hockey League (CWHL). The NWHL season begins its second season Friday, Oct. 7, when the Buffalo Beauts host the Boston Pride, the defending champions. Minnesota and Wisconsin each have seven players competing in the four-team NWHL, while Bemidji State, Ohio State, St. Cloud State and Minnesota Duluth all have one player apiece in the league. Former Wisconsin star and 2012 Patty Kazmaier Award winner Brianna Decker was voted the NWHL’s Most Valuable Player during the league’s inaugural 2015-16 campaign. The 2016-17 season marks the 10th season for the Canadian Women’s Hockey League, with the opening weekend set for Saturday, Oct. 15 and Sunday, Oct. 16. Minnesota Duluth has eight former players in the CWHL, while Ohio State and Wisconsin have three alums on CWHL rosters. Minnesota has two alums and Bemidji State and St. Cloud State each have one player in the league. Former UMD star Caroline Ouellette, a four-time Olympic gold medalist for Team Canada, is the all-time leading scorer in the CWHL. -

Women's Ice Hockey Award Winners

WOMEN’S ICE HOCKEY AWARD WINNERS National Collegiate Awards 2 Division III Awards 4 Special Awards 7 NATIONAL COLLEGIATE AWARDS Second Team F–Sabrina Harbec, St. Lawrence 2012-13 CCM ALL- G–Shari Vogt, Minn. St. Mankato F–Dominique Thibault, UConn D–Carla MacLeod, Wisconsin First Team AMERICA D–Julianne Vasichek, Minn. Duluth 2008-09 G–Noora Raty, Minnesota F–Nicole Corriero, Harvard D–Megan Bozek, Minnesota TEAMS F–Natalie Darwitz, Minnesota First Team D–Monique Lamoureux-Kolls, North F–Gina Kingsbury, St. Lawrence G–Jessie Vetter, Wisconsin Dakota The CCM Hockey All-America D–Kacey Bellamy, New Hampshire F–Brianne Jenner, Cornell Ice Hockey Teams are sponsored 2004-05 D–Jocelyne Larocque, Minn. Duluth F–Amanda Kessel, Minnesota by CCM Hockey and chosen by F–Meghan Agosta, Mercyhurst F–Jocelyne Lamoureux, North Dakota members of the American Hockey First Team F–Hilary Knight, Wisconsin Coaches Association. G–Desi Clark, Mercyhurst F–Sarah Vaillancourt, Harvard Second Team G–Alex Rigsby, Wisconsin D–Molly Engstrom, Wisconsin Second Team D–Lyndsay Wall, Minnesota G–Molly Schaus, Boston College D–Blake Bolden, Boston College 2000-01 F–Natalie Darwitz, Minnesota D–Lauriane Rougeau, Cornell D–Melanie Gagnon, Minnesota F–Alex Carpenter, Boston College First Team F–Caroline Ouellette, Minn. Duluth D–Sasha Sherry, Princeton G–Erika Silva, Northeastern F–Krissy Wendell, Minnesota F–Kendall Coyne, Northeastern F–Rebecca Johnston, Cornell F–Brianna Decker, Wisconsin D–Correne Bredin, Dartmouth Second Team F–Monique Lamoureux, Minnesota D–Courtney Kennedy, Minnesota G–Jody Horak, Minnesota F–Kelli Stack, Boston College F–Jennifer Botterill, Harvard D–Carla MacLeod, Wisconsin 2013-14 F–Maria Rooth, Minn. -

USA Hockey’S Director of Women’S Hockey

T E A M U S A G A M E N O T E S U.S. Women’s National Team vs. Russia Monday, April 18, 2011 • Hallenstadion • 4 p.m. (10 a.m. EDT) TELEVISION: N/A Team USA Communications Manager WEBCAST: N/A Christy Cahill - [email protected] LIVE STATS: bit.ly/WWCLiveStats 617.777.4489 / 079.411.57.18 GAME DAY: The top-seeded and two-time defending world champion United States (1-0-0-0) and No. 5 seed Russia (0-0-0-1) meet in the in the second preliminary-round game of Group A for both teams TEAM USA SCHEDULE & RESULTS at Hallenstadion (capacity: 10,630). The U.S. is coming off a 5-0 blanking of Slovakia to open the tour- Date Opponent Time (Local/EDT)/Result nament yesterday (April 17), while Russia fell to Sweden by a 7-1 score. Team USA arrived in Zurich Thurs., April 7 Canada* L, 1-3 on April 13 after holding a selection/training camp in Ann Arbor, Mich., from April 4-12. Prior to the Fri., April 8 Canada* W, 4-1 final U.S. roster being announced on April 9, the 30-player preliminary team played Canada in a pair Sun., April 17 Slovakia W, 5-0 of pre-tournament games on April 7 and 8. Canada won the first game by a 3-1 score before the U.S. Mon., April 18 Russia 4 p.m./10 a.m. garnered the second win, 4-1. Wed., April 20 Sweden 8 p.m./2 p.m. -

Cornell Hockey Friday, March 19, 2010 Semifinal Losers • 4 P.M

This Week’s Games ECAC Hockey Championship Weekend Saturday, March 20, 2010 CORNELL HOCKEY Friday, March 19, 2010 Semifinal losers • 4 p.m. #11 Brown vs. #2 Cornell • 4 p.m. Semifinal winners • 7 p.m. For more information, contact Cornell Assistant Director of Athletic Communications Kevin Zeise #5 St. Lawrence vs. #3 Union, 7 p.m. Times Union Center • Albany, N.Y. PH: (607) 255-5627 • EMAIL: [email protected] • FAX: (607) 255-9791 • CELL: (603) 748-1268 2009-10 Schedule & Results Men’s Hockey Heads To Albany In Search Of Tournament Title October ITHACA, N.Y. -- The Cornell men’s hockey team will head games on WHCU 870 AM, while Cornell Redcast subscrib- 23 WINDSOR (exhib.) W, 7-0 to Albany, N.Y., for the ECAC Hockey semifinals and cham- ers will also get live streaming audio of both contests. 24 U.S. UNDER-18 TEAM (exhib.) L, 2-3 pionship this weekend, to be played at the Times Union Additionally, live video of the game is available on the 30 NIAGARA W, 3-2 (ot) Center in downtown Albany. The Big Red will face upstart internet through B2 Networks. November Brown in the semifinal before facing either Union or St. 6 DARTMOUTH* W, 5-1 Lawrence in the consolation or championship game on ABOUT THE BIG RED 7 HARVARD* W, 6-3 Saturday. Both semifinals on Friday night will be tele- Cornell advanced to its third straight league champion- 13 at Yale* L, 2-4 vised by the NHL Network, while Saturday’s champion- ship weekend after knocking off ninth-seeded Harvard 14 at Brown* W, 6-0 ship game will be televised live on Fox College Sports and last weekend in the quarterfinal round at Lynah Rink. -

THE LATEST in BOBCAT HOCKEY Fri 2 at Union * 6:00 P.M

Quinnipiac Women’s Ice Hockey 2016-17 Schedule 2016-17 QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY WOMEN’S ICE HOCKEY Date Opponent Time/Result GAME #19: NO. 8/8 QUINNIPIAC VS. UNION September Sun 25 Guelph (Exhibition) W, 6-1 Date: Friday, Dec. 2, 2016 (6 p.m.) Fri 30 Maine W, 5-4 Location: Messa Rink | Schenectady, NY October All-Time Series vs. Union: 25-0-4 Sat 1 Maine W, 3-0 Last 5 vs. Union: 5-0-0 Fri 7 at UConn W, 3-0 Sat 8 at New Hampshire W, 3-0 No. 8/8 Quinnipiac Union Last Meeting: W, 9-0 (Feb. 19, 2016) 11-4-3 Overall 2-12-0 Overall Fri 14 at Mercyhurst L, 2-3 Head Coach Cassie Turner vs. Union: 2-0 Sat 15 at Mercyhurst W, 1-0 5-2-1 ECAC 0-6-0 ECAC Fri 21 at Boston College T, 0-0 Sat 22 Boston College L, 4-1 Fri 28 at Yale * W, 4-1 GAME #20: NO. 8/8 QUINNIPIAC VS. RPI Sat 29 at Brown * W, 8-0 Date: Saturday, Dec. 3, 2016 (3 p.m.) November Location: Houston Field House | Troy, NY Fri 4 Clarkson * L, 4-1 All-Time Series vs. RPI: 14-12-2 Sat 5 St. Lawrence * L, 1-0 Fri 11 at Dartmouth * W, 2-1 Last 5 vs. RPI: 4-0-1 Sat 12 at Harvard * W, 2-1 No. 8/8 Quinnipiac Rensselaer Last Meeting: W, 2-1 ( 2OT - Feb. 27, 2016) 11-4-3 Overall 5-12-1 Overall Fri 18 Cornell * T, 3-3 3-0-1 Sat 21 Colgate * W, 3-1 5-2-1 ECAC 2-4-0 ECAC Head Coach Cassie Turner vs. -

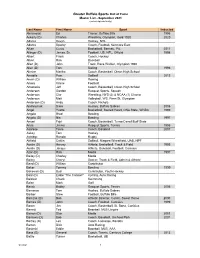

Master List 2019.Xlsx

Greater Buffalo Sports Hall of Fame Master List - September 2021 (sorted alphabetically) Last Name First Name Sport Inducted Abramoski Ed Trainer, Buffalo Bills 1996 Ackerly (D) Charles Wrestling, Olympian, Gold 1920 2020 Adams Kevyn Hockey, NHL Adams Sparky Coach, Football, Kenmore East Aiken Curtis Basketball, Bennett, Pitt 2011 Ailinger (D) James, Dr. Football, UB, NFL, Official 1998 Albert Frank Coach, Hockey Albert Rick Baseball Allen (D) John Track, Race Walker, Olympian 1960 Allen (D) Tom Sailing 1996 Altmire Martha Coach, Basketball, Olean High School Amabile Pam Softball 2013 Aman (D) William Rowing Amoia Vinnie Football Anastasia Jeff Coach, Basketball, Olean High School Anderson Gordon Racquet Sports, Squash Anderson Clar Wrestling, NYS (2) & NCAA (1) Champ Anderson Matt Volleyball, WS, Penn St, Olympian Anderson (D) Andy Coach, Nichols Andreychuk Dave Hockey, Buffalo Sabres 2006 Angel Yvette Basketball, Sacred Heart, Ohio State, WNBA 1999 Angelo Brad Bowling Angelo (D) Nin Bowling 1997 Ansari Fajri Coach, Basketball, TurnerCarroll/Buff State Arias Jimmy Racquet Sports, Tennis 1995 Asarese Tovie Coach, Baseball 2007 Askey Tom Hockey Astridge Ronald Rugby Attfield Caitlin Softball, Niagara Wheatfield, UAB, NPF Austin (D) Harvey Athlete, Basketball, Track & Field 1995 Austin (D) Jacque Athlete, Baseball, Football, Canisius Azar (D) Rick Media 1997 Bailey (D) Charley Media Bailey Cheryl Soccer, Track & Field, Admin & Athlete Baird (D) William Contributor Baker Tommy Bowling 1999 Bakewell (D) Bud Contributor, Youth Hockey Bald (D) Eddie "The Cannon" Cycling, Auto Racing Baldwin Chuck Swimming Balen Mark Golf Banck Bobby Racquet Sports, Tennis 2006 Barrasso Tom Hockey, Buffalo Sabres Barber Stew Football, Buffalo Bills Barczak (D) Bob Athletic Director, Coach, Sweet Home 2000 Barnes (D) John Coach, Football, Canisius 1999 Baron Jim Coach, Basketball, St. -

WCHA SENDS FIVE to the NWHL in the 2020 DRAFT the Minnesota Whitecaps Selected Forward Alex Woken in the First Round

Contact: Todd Bell, Marketing & Communications Manager /O: 952-681-7668 / C: 972-825-6686 / Email: [email protected] Website: wcha.com / Twitter: @wcha_whockey / IG: @wcha_whockey / FB: facebook.com/wchawomenshockey / Watch on FloHockey.tv FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE WCHA SENDS FIVE TO THE NWHL IN THE 2020 DRAFT The Minnesota Whitecaps selected forward Alex Woken in the first round BLOOMINGTON, Minn. – April 30, 2020 – Five alumnae of the Western Collegiate Hockey Association are continuing their hockey careers after being selected in the 2020 National Women’s Hockey League Draft. Alex Woken and Patti Marshall of the University of Minnesota, Presley Norby and Maddie Rowe of the University of Wisconsin and Haley Mack of Bemidji State University were selected by the Minnesota Whitecaps in this year’s draft. The first and second rounds aired on April 28 while the final three rounds were concluded on April 29. Woken earned the first nod of the former WCHA skaters. The Fargo, N.D., native heard her name called in the first round as the Minnesota Whitecaps claimed the 2019-20 WCHA Student-Athlete of the Year with the fifth-overall pick. Marshall followed her former teammate when the Whitecaps selected her in the second round with the 11th-overall pick. Norby joins Woken and Marshall on the Whitecaps roster after Minnesota selected the Wisconsin forward in the third round with the 17th-overall pick. Bemidji State became the third university to see one of their players selected in this year’s draft as Mack went to the Whitecaps with 23rd-overall pick. Rowe rounded out the handful of Whitecaps draftees as the 2019 Isobel Cup Champions chose the former Badgers defender in the fifth round with the 28th -overall pick. -

Team History 20 YEARS of ICEHOGS HOCKEY

Team History 20 YEARS OF ICEHOGS HOCKEY MARCH 3, 19 98: United OCT. 15, 1999: Eighteen DEC. 1, 1999: The awards FEB. 6, 2000: Defenseman Sports Venture launches a months after the first an - continue for Rockford as Derek Landmesser scores the ticket drive to gauge interest nouncement, the IceHogs win Jason Firth is named the fastest goal in IceHogs his - in professional hockey in their inaugural game 6-2 over Sher-Wood UHL Player of tory when he lights the lamp Rockford. the Knoxville Speed in front the Month for November. six seconds into the game in of 6,324 fans at the Metro - Firth racked up 24 points in Rockford’s 3-2 shootout win AUG. 9, 1998: USV and the Centre. 12 games. at Madison. MetroCentre announce an agreement to bring hockey to OCT. 20, 1999: J.F. Rivard DEC. 10, 1999: Rockford al - MARCH 15, 2000: Scott Rockford. turns away 32 Madison shots lows 10 goals for the first Burfoot ends retirement and in recording Rockford’s first time in franchise history in a joins the IceHogs to help NOV. 30, 1998: Kevin Cum - ever shutout, a 3-0 win. 10-5 loss at Quad City. boost the team into the play - mings is named the fran - offs. chise’s first General Manager. NOV. 1, 1999: IceHogs com - DEC. 21, 1999: Jason Firth plete the first trade in team becomes the first IceHogs MARCH 22, 2000: Rock- DEC. 17, 1998: The team history, acquiring defense - player to receive the Sher- ford suffers its worst loss in name is narrowed to 10 names man David Mayes from the Wood UHL Player of the franchise history in Flint, during a name the team con - Port Huron Border Cats for Week award. -

Daily Press Clips March 9, 2021

Buffalo Sabres Daily Press Clips March 9, 2021 Sabres' Rasmus Dahlin experiencing growing pains in new role on defense By Lance Lysowski The Buffalo News March 9, 2021 PHILADELPHIA – Rasmus Dahlin did not hang his head. He didn’t even glance at a group of New York Islanders swarming forward Matt Martin to celebrate their fifth goal Thursday night. Dahlin, now a 20-year-old defenseman and 164 games into a National Hockey League career that began with his selection first overall at the 2018 draft, skated toward the Buffalo Sabres’ bench and used his right hand to lift his stick in the air to signal for a line change. Martin, a fourth-line grinder known more for his right hook than scoring touch, had just skated by Dahlin and across the front of the Sabres’ net before jamming the puck past goalie Jonas Johansson to seal the Islanders' 5- 2 win. In years past, Dahlin’s frustration might have boiled over. One of the NHL’s bright young defensemen, Dahlin has grown accustomed to the sometimes overwhelming emotion that comes with failure. He’s experienced more than his fair share during his third season in the NHL. Entering Monday, Dahlin owned a league-worst minus-21 rating – on pace for minus-75 if this were an 82-game season – and advanced metrics illustrate how he’s struggling at times to adjust to a bigger role defensively. “It comes (down to forgetting) things, it comes (down) to working harder,” Dahlin said matter of factly. “You are allowed to get (upset) at yourself.