Approaches to Media History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Mass Media in the USA»

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BSU Digital Library Mass Media In The USA K. Khomtsova, V. Zavatskaya The topic of the research is «Mass media in the USA». It is topical because mass media of the United States are world-known and a lot of people use American mass media, especially internet resources. The subject matter is peculiarities of different types of mass media in the USA. The aim of the survey is to study the types of mass media that are popular in the USA nowadays. To achieve the aim the authors fulfill the following tasks: 1. to define the main types of mass media in the USA; 2. to analyze the popularity of different kinds of mass media in the USA; 3. to mark out the peculiarities of American mass media. The mass media are diversified media technologies that are intended to reach a large audience by mass communication. There are several types of mass media: the broadcast media such as radio, recorded music, film and tel- evision; the print media include newspapers, books and magazines; the out- door media comprise billboards, signs or placards; the digital media include both Internet and mobile mass communication. [4]. In the USA the main types of mass media today are: newspapers; magazines; radio; television; Internet. NEWSPAPERS The history of American newspapers goes back to the 17th century with the publication of the first colonial newspapers. It was James Franklin, Benjamin Franklin’s older brother, who first made a news sheet. -

The Blogization of Journalism

DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Board of School of Communication, Media and Theatre of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Lecture Room Linna K 103, Kalevantie 5, Tampere, on May 17th, 2014, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE DMITRY YAGODIN The Blogization of Journalism How blogs politicize media and social space in Russia Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Tampere University Press Tampere 2014 ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Communication, Media and Theatre Finland Copyright ©2014 Tampere University Press and the author Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Distributor: [email protected] http://granum.uta.fi Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1934 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1418 ISBN 978-951-44-9450-5 (print) ISBN 978-951-44-9451-2 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://tampub.uta.fi Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print 441 729 Tampere 2014 Painotuote Preface I owe many thanks to you who made this work possible. I am grateful to you for making it worthwhile. It is hard to name you all, or rather it is impossible. By reading this, you certainly belong to those to whom I radiate my gratitude. Thank you all for your attention and critique, for a friendly talk and timely empathy. My special thanks to my teachers. To Ruslan Bekurov, my master’s thesis advisor at the university in Saint-Petersburg, who encouraged me to pursue the doctoral degree abroad. To Kaarle Nordenstreng, my local “fixer” and a brilliant mentor, who helped me with my first steps at the University of Tampere. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A

Marquette Law Review Volume 77 | Issue 2 Article 7 Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics Kristine A. Oswald Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Kristine A. Oswald, Mass Media and the Transformation of American Politics, 77 Marq. L. Rev. 385 (2009). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol77/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASS MEDIA AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICAN POLITICS I. INTRODUCTION The importance of the mass media1 in today's society cannot be over- estimated. Especially in the arena of policy-making, the media's influ- ence has helped shape the development of American government. To more fully understand the political decision-making process in this coun- try it is necessary to understand the media's role in the performance of political officials and institutions. The significance of the media's influ- ence was expressed by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: "The Press has become the greatest power within Western countries, more powerful than the legislature, the executive, and the judiciary. One would then like to ask: '2 By what law has it been elected and to whom is it responsible?" The importance of the media's power and influence can only be fully appreciated through a complete understanding of who or what the media are. -

Journalism (JRN) 1

Journalism (JRN) 1 Journalism (JRN) Courses JRN 1101. Elements of Writing. 2 Credit Hours. This course focuses on the fundamentals of style and language usage necessary for effective writing. Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. JRN 1111. Journalism and Society. 3 Credit Hours. The purpose of this course is to acquaint students with concepts and functions of journalism and the related industries of advertising and public relations in American society. Students will gain knowledge about the history, economics and industry structure of these industries, focusing on how mass media content is determined and disseminated. We will explore underlying values associated with journalism, relationships between journalism and other social institutions, and current issues facing journalists. NOTE: (1) Departmental core course. Normally taken as the first Journalism course. A grade of C or higher is required in order to take higher-level Journalism courses. (2) This course can be used to satisfy the university Core Individual and Society (IN) requirement. Although it may be usable towards graduation as a major requirement or university elective, it cannot be used to satisfy any of the university GenEd requirements. See your advisor for further information. Course Attributes: IN Repeatability: This course may not be repeated for additional credits. JRN 1113. Audio/Visual Newsgathering. 3 Credit Hours. This course will present students with additional story-telling tools by introducing them to basic techniques of reporting with and editing sound and video. The emphasis of this course will be on the use of digital audio and video recorders in the field to produce news stories for radio, television and the web. -

Media Studies and Production Diploam Program Guide

Media Studies and Production Diploma - 31 credits Program Area: Media Studies (Fall 2019) ***REMEMBER TO REGISTER EARLY*** Program Description Required Courses This program is designed to Course Course Title Credits Term prepare the graduate for a wide MCOM 1400* Intro to Mass 3 Communication variety of positions in media MCOM 1420* Digital Video 3 production. Graduates are trained Production for jobs ranging from highly visible MCOM 1422* Audio for the Media 3 on-the-air assignments to positions ENGL 1106* College Composition I 3 on production or news teams. MCOM 1424 Digital Video Editing 3 Graduates can also gain skills MCOM 1426 Project/Production 3 needed for careers in multimedia, Management DVD authoring, film style MCOM 1428* Interactive Media 3 production, and media project & Production MCOM 1795* Portfolio Production 1 production management. Lake MCOM 1797* Media Studies 3 Superior College media studies Internship students receive valuable hands- Electives 6 on experience in LSC’s own audio (refer to Table 1) and video studios, as well as Total credits 31 through internships and *Requires a prerequisite or instructor’s consent experiences at local broadcast stations and media agencies. Program Outcomes Upon graduation, students will be able to: • Shoot and edit single camera media productions using both analog and digital equipment. • Participate in cooperative media production teams. • Voice, record, edit, and produce audio projects, promotions, and commercials using both analog and digital equipment. • Use terms and techniques common to media production and process. Pre-program Requirements Successful entry into this program requires a specific level of skill in the areas of English, mathematics, and reading. -

The Mass Media, Democracy and the Public Sphere

Sonia Livingstone and Peter Lunt The mass media, democracy and the public sphere Book section Original citation: Originally published in Livingstone, Sonia and Lunt, Peter, (eds.) Talk on television audience participation and public debate. London : Routledge, UK, 1994, pp. 9-35. © 1994 Sonia Livingstone and Peter Lunt This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/48964/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2013 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s submitted version of the book section. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Original citation: Livingstone, S., and Lunt, P. (1994) The mass media, democracy and the public sphere. In Talk on Television: Audience participation and public debate (9-35). London: Routledge. Chapter 2 The mass media, democracy and the public sphere INTRODUCTION In this chapter we explore the role played by the mass media in political participation, in particular in the relationship between the laity and established power. -

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies (JAMS)

Journalism, Advertising, and Media Studies Interested in This Major? Current Students: Visit us in Bolton Hall, Room 510B, call us at 414-229-4436 or email [email protected] Not a UWM Student yet? Call our Admissions Counselor at 414-229-7711 or email [email protected] Web: uwm.edu/journalism-advertising-media-studies JAMS at UWM Career Opportunities Media has never been more dynamic. The worlds JAMS students have a wide range of career paths open of journalism, advertising, public relations and film to them. Many seek careers in media, marketing, and are changing and growing at a rapid pace, and the communication. Others go on to pursue graduate work in the Department of Journalism, Advertising, and Media social sciences, humanities, and law. Studies (JAMS) is a great place to learn about them. Our alumni can be found in many prestigious organizations: Whether students see themselves working in news, entertainment, social media, advertising, public • Groupon • SC Johnson relations, or are fascinated by media, JAMS courses • Boston Globe • Milwaukee Brewers enable students to customize their education and • Milwaukee Journal • A.V. Club (Onion, Inc.) prepare for their chosen careers. Sentinel • WI Air National Guard Students choose courses to gain a broad • TMJ4 • United Nations understanding of the media’s place in society and • Foley & Lardner University culture, but also concentrate more closely in one of • Vice News • Boys & Girls Clubs of three areas: • WI State Legislature Greater Milwaukee Journalism. The Journalism concentration emphasizes • Bader Rutter writing, information gathering, critical thinking • New England Journal and technology skills in courses taught by media of Medicine • HSA Bank professionals. -

D4d78cb0277361f5ccf9036396b

critical terms for media studies CRITICAL TERMS FOR MEDIA STUDIES Edited by w.j.t. mitchell and mark b.n. hansen the university of chicago press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2010 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2010 Printed in the United States of America 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5 isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53254- 7 (cloth) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53254- 2 (cloth) isbn- 13: 978- 0- 226- 53255- 4 (paper) isbn- 10: 0- 226- 53255- 0 (paper) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Critical terms for media studies / edited by W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark Hansen. p. cm. Includes index. isbn-13: 978-0-226-53254-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53254-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-13: 978-0-226-53255-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-53255-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Literature and technology. 2. Art and technology. 3. Technology— Philosophy. 4. Digital media. 5. Mass media. 6. Image (Philosophy). I. Mitchell, W. J. T. (William John Th omas), 1942– II. Hansen, Mark B. N. (Mark Boris Nicola), 1965– pn56.t37c75 2010 302.23—dc22 2009030841 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48- 1992. Contents Introduction * W. J. T. Mitchell and Mark B. N. Hansen vii aesthetics Art * Johanna Drucker 3 Body * Bernadette Wegenstein 19 Image * W. -

J366E HISTORY of JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010

J366E HISTORY OF JOURNALISM University of Texas School of Journalism Fall Semester 2010 Instructor: Dr. Tom Johnson Office: CMA 5.155 Phone: 232-3831 email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 1-3:30, by appointment and when you least expect it Class Time: 3:30-5 Tuesday and Thursday, CMA 5.136 REQUIRED READINGS Wm David Sloan, The Media in America: A History (7th Edition). Reading packet: available on library reserve website (see separate sheet for instructions) COURSE DESCRIPTION Development of the mass media; social, economic, and political factors that have contributed to changes in the press. Three lecture hours a week for one semester. Prerequisite: Upper-division standing and a major in journalism, or consent of instructor. OBJECTIVES J 366E will trace the development of American media with an emphasis on cultural, technological and economic backgrounds of press development. To put it more simply, this course will examine the historic relationship between American society and the media. An underlying assumption of this class is that the content and values of the media have been greatly influenced by changes in society over the last 300 years. Conversely, the media have helped shape our society. More specifically, this course will: 1. Examine how journalistic values such as objectivity have evolved. 2. Explain how the media influenced society and how society influenced the media during different periods of our nation's history. 3. Examine who controlled the media at different periods of time, how that control was exercised and how that control influenced media content. 4. Investigate the relationship between the public and the media during different periods of time. -

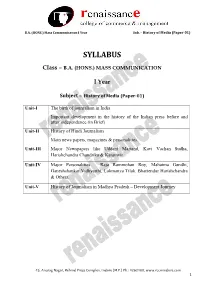

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618).