Ideas of Love That We Will Be Exploring Hereafter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Living in Hope

Armenian-American Museum Advances • Rose McGowan, Ever Brave ® APRIL 27 - MAY 3, 2018 / VOL. 40 / NO. 23 LAWEEKLY.COM LIVINGAS BOYLE HEIGHTS THEATER COMPANY IN CASA 0101HOPE FIGHTS FOR ITS LIFE, FUNDING TO IMPROVE ARTISTIC DIVERSITY DWINDLES BY BILL RADEN | 2 | WEEKLY JACOBY&MEYERS LA INJURY LAWYERS AUTO & TRUCK ACCIDENTS • MOTORCYCLE ACCIDENTS • PERSONAL INJURY America’s Most Trusted Law Firm For over 40 years, Jacoby & Meyers has been “ protecting injury victims and their families. “ Call us today for a free confidential consultation. www.laweekly.com www.laweekly.com 3, 2018 // // April 27 - May - LEONARD JACOBY Founding Attorney OVER ONE BILLION DOLLARS IN VERDICTS & SETTLEMENTS Our experienced team of lawyers is here to help you if you’ve been injured and it’s not your fault. 98.7% Win Rate 100% Free Consultation Not your average law firm. Clients hire us because Get a free no-obligation consultation to find we’re committed, relentless, and we win. out how we can help you if you have a case. No Fees Unless We Win Immediate Response 24/7 We work on a contingency basis, which means we Our staff is always available for you when you don’t charge a penny unless we win your case. need to get in touch with us. Award Winning Attorneys Over $1 Billion+ Recovered Our team consists of some of the the nation’s top We have a 40+ year track record of winning attorneys, retired judges and former prosecutors. and helping our clients get to a better place. INJURED? CALL FOR FREE CONSULTATION 1-800-992-2222 www.JacobyandMeyers.com © 2018 Jacoby & Meyers - All rights reserved. -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

Poetry Library

Poetry Library All your ‘Poems of the Week’ in one collection w/c 14.05.20 Atlas by U.A Fanthorpe There is a kind of love called maintenance Which stores the WD40 and knows when to use it; Which checks the insurance, and doesn’t forget The milkman; which remembers to plant bulbs; Which answers letters; which knows the way The money goes; which deals with dentists And Road Fund Tax and meeting trains, And postcards to the lonely; which upholds The permanently ricketty elaborate Structures of living, which is Atlas. And maintenance is the sensible side of love, Which knows what time and weather are doing To my brickwork; insulates my faulty wiring; Laughs at my dryrotten jokes; remembers My need for gloss and grouting; which keeps My suspect edifice upright in air, As Atlas did the sky. w/c 21.05.20 This week we've chosen a couple of poems written by Dorset HealthCare colleagues. The first is by Suzie Thomas after undergoing an operation and she'd like to dedicate it to all the frontline staff who are putting themselves in harms way for the rest of us. The second is by Adele Sales, imagining the world on the other side of the pandemic. Walking Angels (NHS) by Suzie Thomas, E-procurement Co-ordinator If only there were people who toiled and cared for everyone out there? If only there were people who at our darkest moments of turmoil and fear were there to care? People who would tuck you in bed with love and compassion Even though they’d been dashing to another, even though they themselves are crashing. -

Fu ~ !;; Uad When

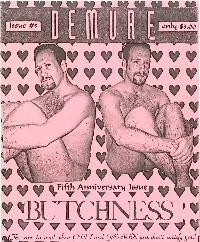

• v ~fu_~ !;;_uad when <D'llCJ and §CdVJ?E juit don't iatii{y you! [ FROM THE EDITOR Sloppy Sentimentality from your favorite person Here we go again! I myself can't believe this is #5. What staned out as a.fun little hobby has mushroom-clouded into a rather popular underground extravaganza. I'm now gelling more out ofstate orders than Minnesota sales. I've got/en groovy reviews from Wisconsin, Chicago and California and people send me free books and eds to review. I've even had the pleasure ofpissing offsome tight-asses (and will no doubtedly do it again with this issue!) Yes, zinedom is the life! Thanks/or reading this shit! Big news! In special celebration of the 5th Anniversary Issue, I am very hooored to bring back one ofmy original co-editors to write some columns. And I can even reveal his true identity. Yes, the bitch Sarah Tynge-Mayhem from DB #1 is none other than Mssr. Michael Moeglin, the laziest, most talented· writer I personally know (besides Troy Tradup and Michael Dahl). He's back to wreak havoc on DB and to generally ... entenain! Welcome back Michael! About this issue: In addition to our regular columnists (write in to which ones you like and don't like), this is a retro anniversary of sequels. Hence, a new queer quiz, more men I'm embarrassed to like, and another drag hag review. Ifyou like these, go back and order back issues for the originals (SSP ALERT!!!) I always keep back issues in stock (WARNING! SSP ALERT!!!) and some loyal readers are even ordering complete sets for the perfect Christmas gift (WARNING! SSP JS NOW AT A TOXIC LEVEL!!!). -

The Donation Dedicated to Jerry and Karen's Parents Various The

The Donation Dedicated To Jerry and Karen's Parents Various The Golden Greats CPS 291 Columbia VG/ Easy Special VG+ Listening Products Andy Williams The Great Songs LE Columbia F+/ Easy From My Fair 10097 G- Listening Lady Andy Williams Moon River And CS 8609 Columbia F+/ ft. The Williams Easy G- Brothers, Claudine Listening Other Great Movie Williams And The Themes Entire Williams Family Andy Williams The Wonderful CS 8937 Columbia VG-/ Easy World Of VG Listening Andy Williams Solitaire KC Columbia VG/ Easy 32383 VG+ Listening Barry Manilow Greatest Hits A2L Arista VG/ Double Easy 8601 VG+ Album/ Listening Gatefold Barry Manilow This One's For You AL 4090 Arista VG/ Easy VG+ Listening Barry Manilow Even Now AB 4164 Arista VG/ Easy VG+ Listening Robert Goulet Always You CS 8476 Columbia VG/ music by De Vo Easy VG+ Listening Robert Goulet Sincerely Yours... CL 1931 Columbia VG/ Easy VG+ Listening Robert Goulet In Person CL 2088 Columbia VG/ recorded live in Easy VG+ concert Listening Englebert Live At The XPAS Parrot VG/ Gatefold Easy Humperdinck Riviera Hotel Las 71051 (London) VG+ Listening Vegas Englebert The Last Waltz PAS- Parrot VG Easy Humperdinck 71015 (London) Listening Eddie Fisher When I Was Young DLP DOT G-/G Easy 3648 Listening Eddie Fisher Games That Lovers LPS RCA Victor VG/ Arr. & Cond. By Easy Play 3726 VG+ Nelson Riddle Listening Mantovani And ...Memories PS 542 London VG Easy His Orchestra Listening Bobby Vinton Ballads Of Love H-1029 Heartland G+/ Easy VG- Listening 1 The Donation Dedicated To Jerry and Karen's Parents Kate Smith The Fabulous CAS- RCA VG/ Easy 2439 (Camden) VG+ Listening Johnny Mathis More Johnny's CL 1344 Columbia VG/ Easy Greatest Hits VG+ Listening Jane Olivor The Best Side Of JC Columbia G+/ Easy Goodbye 36335 VG- Listening Don Ho 30 Hawaiian SMI-1- Suffolk G+/ Easy Favorites 17G Marketing VG- Listening Inc. -

Of ABBA 1 ABBA 1

Music the best of ABBA 1 ABBA 1. Waterloo (2:45) 7. Knowing Me, Knowing You (4:04) 2. S.O.S. (3:24) 8. The Name Of The Game (4:01) 3. I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do (3:17) 9. Take A Chance On Me (4:06) 4. Mamma Mia (3:34) 10. Chiquitita (5:29) 5. Fernando (4:15) 11. The Winner Takes It All (4:54) 6. Dancing Queen (3:53) Ad Vielle Que Pourra 2 Ad Vielle Que Pourra 1. Schottische du Stoc… (4:22) 7. Suite de Gavottes E… (4:38) 13. La Malfaissante (4:29) 2. Malloz ar Barz Koz … (3:12) 8. Bourrée Dans le Jar… (5:38) 3. Chupad Melen / Ha… (3:16) 9. Polkas Ratées (3:14) 4. L'Agacante / Valse … (5:03) 10. Valse des Coquelic… (1:44) 5. La Pucelle d'Ussel (2:42) 11. Fillettes des Campa… (2:37) 6. Les Filles de France (5:58) 12. An Dro Pitaouer / A… (5:22) Saint Hubert 3 The Agnostic Mountain Gospel Choir 1. Saint Hubert (2:39) 7. They Can Make It Rain Bombs (4:36) 2. Cool Drink Of Water (4:59) 8. Heart’s Not In It (4:09) 3. Motherless Child (2:56) 9. One Sin (2:25) 4. Don’t We All (3:54) 10. Fourteen Faces (2:45) 5. Stop And Listen (3:28) 11. Rolling Home (3:13) 6. Neighbourhood Butcher (3:22) Onze Danses Pour Combattre La Migraine. 4 Aksak Maboul 1. Mecredi Matin (0:22) 7. -

Voices of Compton ������������������ Compton Literary / Arts Journal Dr

Acknowledgements Voices of Compton Compton Literary / Arts Journal Dr. Keith Curry, CEO Ms. Barbara Perez, Vice President Mr. Robert Butler, Student Life Office Mr. Cleveland Palmer, Contributor of Student Artwork Ms. Chelvi Subramaniam, Humanities Chair Dr. Ruth Roach, Publication Coordinator & English Faculty Mr. Jose Bernaudo, Reader & English Faculty Mr. David Maruyama, Reader & English Faculty Ms. Toni Wasserberger, Reader & English Faculty Mr. Patrick McLaughlin, First Year Experience & English Faculty Ms. Amber Gillis, Advisory Team Member and Faculty Member Associated Student Body & Humanities Division Faculty Cover Artwork: Jennifer Deese, Dalia Cornejo, Tyler Sims, Luis Mota, Amy Huerta Cruz, Violeta Martinez, Adriana Sanchez, Marysol Ortiz 2011-2012 Publisher: Southern California Graphics® ©Copyright 2012 All rights reserved. 1 2 Table of Contents |30| Poem about My Own People (Poem) by Lonnie Manuel UPTOWN |31| Man-child: My |40| Emergency Room Pages [13] My Sense of Identity Experience (Essay) (Essay) [4] A Father’s Love (Poem) (Essay) by David Richardson by Jaime Yoshida by Stephanie Bentley by Desiree Lavea |32| Poverty: My Experience |43| “Underdog” (Poem) [4] Self Portrait (Sketch) [15] Love Is (Poem) (Essay) by Carlos Ornelas by Tony McGee by Erica Monique Greer by Rodney Bunkley |43| The Joker (Painting) [5] Untitled (Sketch) [16] Love Confessions |34| Depression from by Ricardo Villeda (Guest) by Tony McGee by Danny Westbrook Oppression (Essay) |44| Children of the Universe [5] Rikki (Poem) [16] Have You Seen the -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

December 1978 College of Boca Raton Vol

DECEMBER 1978 COLLEGE OF BOCA RATON VOL. VII NO. III Dr. Ross Views Fall Semester by Catherine Amann who come with' different ideas foreign countries and from 40 Associate Editor - visions of surfboards and states, we have a truly swimming. They've found that international student body, and As the Fall semester draws to there is more to this institution Dr. Ross went on tosaythatthis an end, Dr. Donald Ross, than its beautiful facilities. mixture of many different President of CBR, summarizes There is a real seriousness of types of people has succeeded in these past three and a half purpose. After all, there are blending well together. months and shares his feelings few colleges in this country with us. where the students can get Sometimes Dr. Ross is small classes with such a invited to visit other institu "I think the college has tions, and other college repre developed a real sense of dedicated faculty. More than that, to be able to walk into the sentatives likewise are invited academic seriousness in our to visit us. Dr. Ross says that student body. I am amazed at dean's office and the president's office, and have that kind of whenever we have visitors, and the number of students sitting they stroll around the campus in the library night and day, personal relationship is what this institution is all about." grounds, they are impressed and in the cafeteria with books with the many friendly smiles open intensely studying. The Realistically, Dr. Ross and the numerous hellos and college dorms are relatively mentioned that with every new the generally friendly attitude quiet and in talking to the year, we do lose some students of the students on this campus, upperclassmen, they tell me who find they cannot fit in with more so than other institutions. -

Alexander O'neal Album and 1985 and Download and Blog Alexander O'neal Album and 1985 and Download and Blog

alexander o'neal album and 1985 and download and blog Alexander o'neal album and 1985 and download and blog. 1) Select a file to send by clicking the "Browse" button. You can then select photos, audio, video, documents or anything else you want to send. The maximum file size is 500 MB. 2) Click the "Start Upload" button to start uploading the file. You will see the progress of the file transfer. Please don't close your browser window while uploading or it will cancel the upload. 3) After a succesfull upload you'll receive a unique link to the download site, which you can place anywhere: on your homepage, blog, forum or send it via IM or e-mail to your friends. IsraBox - Music is Life! Alexander O'Neal - This Thing Called Love The Greatest Hits of Alexander O'Neal (1992) Artist : Alexander O'Neal Title : This Thing Called Love The Greatest Hits of Alexander O'Neal Year Of Release : 1992 Label : EPIC Genre : Soul, RnB Quality : FLAC (image+.cue, log) Total Time : 1:01:43 Total Size : 414 MB. Alexander O'Neal - Greatest Hits (2004) FLAC. Artist : Alexander O'Neal Title : Greatest Hits Year Of Release : 2004 Label : Virgin [7243 5 78502 2 3] Genre : R&B, Soul, Funk Quality : FLAC (tracks+cue, log) Total Time : 1:17:21 Total Size : 566 mb. Alexander O'Neal - Greatest Hits (2004) Artist : Alexander O'Neal Title : Greatest Hits Year Of Release : 2004 Label : Virgin Genre : R&B, Soul, Funk Quality : mp3 / CBR 320 kbps Total Time : 01:17:22 Total Size : 187 mb (+5%rec.) Alexander O'Neal - Lovers Again (1997) Artist : Alexander O'Neal Title : Lovers Again Year Of Release : 1997 Label : Orange Leisure Genre : Funk, Soul, R&B Quality : MP3/320 kbps Total Time : 00:57:20 Total Size : 131 mb. -

Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien De Troyes

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Honors Theses Student Research 2014 Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien de Troyes Adele Priestley Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses Part of the Other English Language and Literature Commons Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Priestley, Adele, "Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chretien de Troyes" (2014). Honors Theses. Paper 717. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/honorstheses/717 This Honors Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Failures of Chivalry and Love in Chrétien de Troyes Adele Priestley Honors Thesis Fall 2013 Advisor: Megan Cook Second Reader: James Kriesel Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………… 1-18 Erec and Enide …………………………………………………………….. 19-25 Cliges ……………………………………………………………………….. 26-34 The Knight of the Cart …………………………………………………….. 35-45 The Knight with the Lion ……………………………………………….…. 46-54 The Story of the Grail …………………………………………………….. 55-63 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………. 64-67 Works Cited ……………………………………………………………….. 68-70 1 Introduction: Chrétien’s Chivalry and Courtly Love Although there are many authors to consider in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Chrétien de Troyes stands out as a forerunner in early romances. It is commonly accepted that he wrote his stories between 1160 and 1191, which was a time period marked by a new movement of romantic literature.