Effects of Political Economy on Development in Cote D'ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O M M U N I Q

MINISTERE DE LA CONSTRUCTION, DU LOGEMENT REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DE L'URBANISME Union - Discipline - Travail LE MINISTRE Abidjan, le N ________/MCLAU/CAB/bfe C O M M U N I Q U E Le Ministre de la Construction, de l’Assainissement et de l’Urbanisme a le plaisir d’informer les usagers demandeurs d’arrêté de concession définitive, dont les noms sont mentionnés ci-dessous que les actes demandés ont été signés et transmis à la Conservation Foncière. Les intéressés sont priés de se rendre à la Conservation Foncière concernée en vue du paiement du prix d'aliénation du terrain ainsi que des droits et taxes y afférents. Cinq jours après le règlement du prix d'aliénation suivi de la publication de votre acte au livre foncier, vous vous présenterez pour son retrait au service du Guichet Unique du Foncier et de l'Habitat. -

To the Management of Surface Water Resources in the Ivory Coast Basin of the Aghien Lagoon

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 10, October-2019 1605 ISSN 2229-5518 Application of the water evaluation and planning model (WEAP) to the management of surface water resources in the Ivory Coast basin of the Aghien lagoon 1Dabissi NOUFÉ Djibril, 2ZAMBLE Armand Tra Bi, 1DIALLO Seydou, 1SORO Emile Gnénéyougo, 1DAO Amidou, 1DIOMANDE Souleymane, EFFEBI Kôkôh Rose, 1KAMAGATÉ Bamory, 1GONÉ Droh Laciné, 3PATUREL Jean-Emmanuel, 2MAHE Gil, 1GOULA Bi Tié Albert, 3SERVAT Éric. Abstract —Water, an essential element of life, is of paramount importance in our countries, where it is increasingly scarce and threatened; we are constantly maintained by news where pollution, scarcity, flooding are mixed. As a result of cur- rent rapid climatic and demographic changes, the management of water resources by human being is becoming one of the major challenges of the 21st century, as water becoming an increasingly limited resource. It will now be necessary to use with modera- tion. This study is part of the project "Aghien Lagoon" (Abidjan) and its potential in terms of safe tape water resources. Mega- lopolis of about six million inhabitants (RGPH, 2014), Abidjan encounters difficulties of access to safe tape water due to the de- cline of the underground reserves and the increase the demand related to urban growth. Thus, the Aghien lagoon, the largest freshwater reserve near Abidjan, has been identified by the State of Côte d'Ivoire as a potential source of additive production of safe tape water. However, urbanization continues to spread on the slopes of this basin, while, at the same time, market garden- ing is developing, in order to meet the demand. -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

Liste Des Centres De Collecte Du District D'abidjan

LISTE DES CENTRES DE COLLECTE DU DISTRICT D’ABIDJAN Région : LAGUNES Centre de Coordination: ABIDJAN Nombre total de Centres de collecte : 774 ABIDJAN 01 ABOBO Nombre de Centres de collecte : 155 CODE CENTRE DE COLLECTE 001 EPV CATHOLIQUE ST GASPARD BERT 002 EPV FEBLEZY 003 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LE PROVENCIAL ABOBO 004 COLLEGE PRIVE DJESSOU 006 COLLEGE COULIBALY SANDENI 008 G.S. ANONKOUA KOUTE I 009 GROUPE SCOLAIRE MATHIEU 010 E-PP AHEKA 011 EPV ABRAHAM AYEBY 012 EPV SAHOUA 013 GROUPE SCOLAIRE EBENEZER 015 GROUPE SCOLAIRE 1-2-3-4-5 BAD 016 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINT MOISE 017 EPP AGNISSANKO III 018 EPV DIALOGUE ET DESTIN 2 019 EPV KAUNAN I 020 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABRAHAM AYEBY 021 EPP GENDARMERIE 022 GROUPE SAINTE FOI ABIDJAN 023 G. S. LES AMAZONES 024 EPV AMAZONES 025 EPP PALMERAIE 026 EPV DIALOGUE 1 028 INSTITUT LES PREMICES 030 COLLEGE GRACE DIVINE 031 GROUPE SCOLAIRE RAIL 4 BAD B ET C 032 EPV DIE MORY 033 EPP SAGBE I (BOKABO) 034 EPP ATCHRO 035 EPV ANOUANZE 036 EPV SAINT PAUL 037 EPP N'SINMON 039 COLLEGE H TAZIEFE 040 EPV LESANGES-NOIRS 041 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSAMOI 045 COLLEGE ANADOR 046 EPV LA PROVIDENCE 047 EPV BEUGRE 048 GROUPE SCOLAIRE HOUANTOUE 049 EPV SAINT-CYR 050 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE JEANNE 051 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE ELISABETH 052 EPP PLATEAU-DOKUI BAD 054 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE ANNEXE 055 GROUPE SCOLAIRE FENDJE 056 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE 057 EPV CATHOLIQUE SAINT AUGUSTIN 058 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LES ORCHIDEES 059 CENTRE D'EDUCATION PRESCOLAIRE 060 EPV REUSSITE 061 EPP GISCARD D'ESTAING 062 EPP LES FLAMBOYANTS 063 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSEMBLEE -

Promoteurs Agrees Dans Le Cadre Du Programme Des Logements Sociaux Et Leurs Differents Sites

MINISTERE DE LA CONSTRUCTION, DU LOGEMENT, REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D’IVOIRE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DE L’URBANISME Union – Discipline – Travail ---------------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DU LOGEMENT ET DU CADRE DE VIE ---------------------- PROMOTEURS AGREES DANS LE CADRE DU PROGRAMME DES LOGEMENTS SOCIAUX ET LEURS DIFFERENTS SITES N° SOCIETE NOM ET CONTACT Parcelles Localités Superficie m² observations PRENOMS attribuées 1 AGINEC GROUPE POGRAWA 22 01 45 36 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 MOUMOUNI 08 16 42 49 INTERIEUR Agboville 64 300 2 BISMACK ENOK KONE MOUSSA 05 82 64 64 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 HOLDING 08 46 68 68 INTERIEUR Toumodi 51 000 3 CNE-CI-TP N’SIKAN Mme GUIRO 08 17 62 87 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 Epse 01 86 79 79 MAGUIRAGA O. 22 42 20 79 04 04 54 65 INTERIEUR Man 70 775 4 EGBV BAMBA 22 00 70 78 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 INTERNATIONALE AMADOU 01 73 73 91 INTERIEUR Bouna 50 000 5 EGC CI KESSIE ADIBO 20 01 10 90 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 AMBROISE 07 04 82 05 07 97 43 18 02 22 06 56 INTERIEUR Gagnoa 35 096 N° SOCIETE NOM ET CONTACT Parcelles Localités Superficie m² observations PRENOMS attribuées 6 ENTREPRISE ADOU KOUADIO 22 43 49 04 ABIDJAN Bassam 110 000 MOUROUFIE 05 05 20 63 01 08 62 23 INTERIEUR Abengourou 53 100 7 ETABLISSEMENT ABDALLAH 21 24 54 95 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 CYGNES TOUFIC 48 10 90 10 07 80 32 76 INTERIEUR Sassandra 52 500 8 GROUPE AMAOS KOUASSI KOFFI 22 43 15 95 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 FELIX 05 05 21 80 09 85 13 66 INTERIEUR Daoukro 34 300 07 53 99 20 9 GROUPE GENIE DIABATE SINKO 21 28 49 40 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 BATIM-THARA IM 07 98 07 98 07 07 16 76 INTERIEUR Odienné 11 200 10 INTERBAT GRANT-YOBOU 22 41 41 37 ABIDJAN Songon 110 000 BESSIKOUA S.F. -

Annual Report 2017

WCF Siège & Secrétariat 69 chemin de Planta, 1223 Cologny, Switzerland WCF Head Office c/o Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Deutscher Platz 6, 04103 Leipzig, Deutschland Internet: www.wildchimps.org Email: [email protected] WCF West Africa Office WCF Guinea Office WCF Liberia Office 23 BP 238 ONG Internationale FDA Compound - Whein Town Abidjan 23, Côte d’Ivoire 1487P Conakry, Guinée Monrovia, Liberia Annual Report 2017 Activities of the Wild Chimpanzee Foundation for improved conservation of chimpanzees and their habitat in West Africa © Sonja Metzger / WCF February 2018 1 Table of Contents 1. Activities in the Taï-Grebo-Sapo Forest Complex, Liberia and Côte d’Ivoire ......... 12 1.1. Creation of Grebo-Krahn National Park ............................................................... 12 1.2. Biomonitoring and Law Enforcement in the Taï-Grebo-Sapo Forest Complex .... 12 1.2.1. Biomonitoring in the Proposed Krahn-Bassa Conservation Area ........................ 12 1.2.2. Biomonitoring in priority sites of Taï National Park ........................................... 15 1.2.3. Biomonitoring with camera traps in Taï National Park ....................................... 16 1.2.4. Eco-guard program at Grebo-Krahn National Park ............................................. 17 1.2.5. Sapo Task Force and law enforcement at Sapo National Park ............................. 17 1.2.6. Monitoring the Cavally Classified Forest ............................................................ 18 1.2.7. Local NGOs’ actions in Cavally Classified Forest .............................................. 19 1.3. Awareness raising campaigns and capacity building in the TGSFC ..................... 20 1.3.1. Awareness raising around Grebo-Krahn National Park ....................................... 20 1.3.2. Theater tour around the Cavally Classified Forest ............................................... 21 1.3.3. Panel discussion about deforestation in Cavally Classified Forest ....................... 22 1.3.4. -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

Assessment of the Implementation of Alternative Process Technologies for Rural Heat and Power Production from Cocoa Pod Husks

Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Master of Science Thesis KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management Department of Energy Technology Division of Heat and Power Technology SE-100 44 STOCKHOLM Master of Science Thesis EGI 2016: 034 MSC EKV1137 Assessment of the implementation of alternative process technologies for rural heat and power production from cocoa pod husks Dimitra Maleka Approved Examiner Supervisors Reza Fakhraie Reza Fakhraie (KTH) David Bauner (Renetech AB) Commissioner Contact person ii Abstract Cocoa pod husks are generated in Côte d’Ivoire, in abundant quantities annually. The majority is left as waste to decompose at the plantations. A review of the ultimate and proximate composition of CPH resulted in the conclusion that, CPH is a high potential feedstock for both thermochemical and biochemical processes. The main focus of the study was the utilization of CPH in 10,000 tons/year power plants for generation of energy and value-added by-products. For this purpose, the feasibility of five energy conversion processes (direct combustion, gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization) with CPH as feedstock, were investigated. Several indicators were used for the review and comparison of the technologies. Anaerobic digestion and hydrothermal carbonization were found to be the most suitable conversion processes. For both technologies an analysis was conducted including technical, economic, environmental and social aspects. Based on the characterization of CPH, appropriate reactors and operating conditions were chosen for the two processes. Moreover, the plants were chosen to be coupled with CHP units, for heat and power generation. -

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

The Trial of Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé at the ICC

Open Society Justice Initiative BRIEFING PAPER The Trial of Laurent Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé at the ICC JAJ January 2016 Laurent Koudou Gbagbo, former president of Côte d’Ivoire, faces charges at the ICC for crimes against humanity committed in the aftermath of contested presidential elections in 2010. Charles Blé Goudé, Gbagbo’s Youth Minister and long-time supporter, is facing similar charges. The two will be tried together before the ICC for allegedly conspiring to keep Gbagbo in office by any means necessary—including by committing crimes against humanity. 224 West 57th Street, New York, New York, 10019, United States | TEL +1-212-548-0600 | FAX +1-212-548-4662 | [email protected] BRIEFING PAPER GBAGBO AND BLÉ GOUDÉ 2 The Defendants Laurent Koudou Gbagbo is the former president of Côte d’Ivoire. Prior to assuming the presidency in 2000, Gbagbo was a historian and a political dissident. After secretly founding the Front Populaire Ivoirien (Ivorian Popular Front (FPI)) as an opposition party to President Felix Houphouët-Boigny’s one-party rule, Gbagbo spent most of the 1980s in exile in France. Gbagbo returned to Côte d’Ivoire in 1988 to compete against incumbent Houphouet-Boigny in the 1990 presidential race, the country’s first multi-party elections. Though defeated for the presidency, Gbagbo later won a seat in the National Assembly. Amid ongoing political and ethnic unrest throughout Côte d’Ivoire, Gbagbo won the highly contentious and violent 2000 Ivorian presidential elections. Gbagbo remained president until 2010, when he was defeated in a highly contentious presidential election by Alassane Ouattara. -

Côte D'ivoire

Côte d’Ivoire Human Rights Violations in Abidjan during an Opposition Demonstration - March 2004 Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper, October 2004 Introduction................................................................................................................................... 1 Background to Events Surrounding the March 25, 2004 Demonstration ........................... 2 The Ivorian Government Position............................................................................................. 4 Violations by Pro-Government forces: Ivorian Police, Gendarmes and Army .................. 6 Violations by Pro-Government Forces: Militias and FPI Militants ..................................... 9 The Role of Armed Demonstrators.........................................................................................12 Mob Violence by the Demonstrators ......................................................................................14 Lack of Civilian Protection by Foreign Military Forces........................................................16 Legal Aspects ...............................................................................................................................17 Conclusion....................................................................................................................................18 Introduction The events associated with a demonstration in the Ivorian commercial capital of Abidjan by opposition groups planned for March 25, 2004, were accompanied by a deadly crackdown by government -

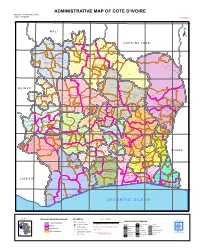

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana