Côte D'ivoire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O M M U N I Q

MINISTERE DE LA CONSTRUCTION, DU LOGEMENT REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ET DE L'URBANISME Union - Discipline - Travail LE MINISTRE Abidjan, le N ________/MCLAU/CAB/bfe C O M M U N I Q U E Le Ministre de la Construction, de l’Assainissement et de l’Urbanisme a le plaisir d’informer les usagers demandeurs d’arrêté de concession définitive, dont les noms sont mentionnés ci-dessous que les actes demandés ont été signés et transmis à la Conservation Foncière. Les intéressés sont priés de se rendre à la Conservation Foncière concernée en vue du paiement du prix d'aliénation du terrain ainsi que des droits et taxes y afférents. Cinq jours après le règlement du prix d'aliénation suivi de la publication de votre acte au livre foncier, vous vous présenterez pour son retrait au service du Guichet Unique du Foncier et de l'Habitat. -

To the Management of Surface Water Resources in the Ivory Coast Basin of the Aghien Lagoon

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 10, Issue 10, October-2019 1605 ISSN 2229-5518 Application of the water evaluation and planning model (WEAP) to the management of surface water resources in the Ivory Coast basin of the Aghien lagoon 1Dabissi NOUFÉ Djibril, 2ZAMBLE Armand Tra Bi, 1DIALLO Seydou, 1SORO Emile Gnénéyougo, 1DAO Amidou, 1DIOMANDE Souleymane, EFFEBI Kôkôh Rose, 1KAMAGATÉ Bamory, 1GONÉ Droh Laciné, 3PATUREL Jean-Emmanuel, 2MAHE Gil, 1GOULA Bi Tié Albert, 3SERVAT Éric. Abstract —Water, an essential element of life, is of paramount importance in our countries, where it is increasingly scarce and threatened; we are constantly maintained by news where pollution, scarcity, flooding are mixed. As a result of cur- rent rapid climatic and demographic changes, the management of water resources by human being is becoming one of the major challenges of the 21st century, as water becoming an increasingly limited resource. It will now be necessary to use with modera- tion. This study is part of the project "Aghien Lagoon" (Abidjan) and its potential in terms of safe tape water resources. Mega- lopolis of about six million inhabitants (RGPH, 2014), Abidjan encounters difficulties of access to safe tape water due to the de- cline of the underground reserves and the increase the demand related to urban growth. Thus, the Aghien lagoon, the largest freshwater reserve near Abidjan, has been identified by the State of Côte d'Ivoire as a potential source of additive production of safe tape water. However, urbanization continues to spread on the slopes of this basin, while, at the same time, market garden- ing is developing, in order to meet the demand. -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

INSTITUT DES FILLES DE MARIE AUXILIATRICE Province AFO, Mère De Dieu Des Filles De Marie Auxiliatrice

INSTITUT DES FILLES DE MARIE AUXILIATRICE Province AFO, Mère de Dieu des Filles de Marie Auxiliatrice LE CHARISME SALESIEN EN AFRIQUE DE L’OUEST UNE GRAINE EN CROISSANCE Visages – Histoire – Témoignages Pascaline Adjovi AFFOGNON Rome, année 2015-2017 A chaque Fille de Marie Auxiliatrice missionnaire en Afrique A toutes les personnes de bonne volonté qui les ont soutenues dans la mission éducative. 2 INDICE ENTRETIENS SUR LE CHARISME SALÉSIEN EN AFRIQUE DE L’OUEST AVEC: M. Mawulikplimi AFFOGNON ............................................................................................ 6 Mme Thérèse AMEZIAN .................................................................................................... 12 Mlle Synhtia ANVOH ......................................................................................................... 16 Mlle. Pierrette WAKLATI, épouse KPONTON ................................................................. 20 Mlle Lyliane SANOGO ....................................................................................................... 23 Mme Mery PATER MANEAZUE ........................................................................................ 26 Sr. Anne Marie ou Marianne PANWAY ............................................................................. 28 Sr. Jocelyne épouse SIERIAKUE BEDOUMOU................................................................ 31 Sr. Yvette DJOSSOU ........................................................................................................... 34 Sr. Asunción -

Mercury Concentration Profile in Sediment Cores of a Tropical Lagoon Under High Anthropogenic Activities Around an Urban City—Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire

Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 2021, 9, 83-94 https://www.scirp.org/journal/gep ISSN Online: 2327-4344 ISSN Print: 2327-4336 Mercury Concentration Profile in Sediment Cores of a Tropical Lagoon under High Anthropogenic Activities around an Urban City—Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Achille Gueu1,2*, Sébastien Koffi Ouffoué2,3, Bruno Zeli Digbéhi1 1Laboratoire de géologie marine, Université Félix Houphouët BOIGNY, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 2Centre Ivoirien Antipollution, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire 3Laboratoire de chimie organique et de substances naturelles, Université Félix Houphouët BOIGNY, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire How to cite this paper: Gueu, A., Ouffoué, Abstract S. K., & Digbéhi, B. Z. (2021). Mercury Con- centration Profile in Sediment Cores of a The present study focuses on the quantification of mercury in sediment cores Tropical Lagoon under High Anthropo- from Cocody, Banco, Koumassi and Milliardaires bays in Abidjan, Côte genic Activities around an Urban City— d’Ivoire. It aims at assessing the state of mercury contamination of the lagoon Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Journal of Geos- cience and Environment Protection, 9, 83- bottom using DMA-80 (Direct Mercury Analyser). The automatic analyzer 94. DMA-80 mercury is an innovative instrument for the analysis of mercury at https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2021.95007 very low content in solid and liquid samples in five minutes, without requir- Received: March 8, 2021 ing any prior steps of pretreatment wet. The results showed, according to the Accepted: May 25, 2021 lithological description of different bays, that the cored sediments consist of Published: May 28, 2021 mud, sand, sandy mud or muddy sand with occasional shells. -

Liste Des Centres De Collecte Du District D'abidjan

LISTE DES CENTRES DE COLLECTE DU DISTRICT D’ABIDJAN Région : LAGUNES Centre de Coordination: ABIDJAN Nombre total de Centres de collecte : 774 ABIDJAN 01 ABOBO Nombre de Centres de collecte : 155 CODE CENTRE DE COLLECTE 001 EPV CATHOLIQUE ST GASPARD BERT 002 EPV FEBLEZY 003 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LE PROVENCIAL ABOBO 004 COLLEGE PRIVE DJESSOU 006 COLLEGE COULIBALY SANDENI 008 G.S. ANONKOUA KOUTE I 009 GROUPE SCOLAIRE MATHIEU 010 E-PP AHEKA 011 EPV ABRAHAM AYEBY 012 EPV SAHOUA 013 GROUPE SCOLAIRE EBENEZER 015 GROUPE SCOLAIRE 1-2-3-4-5 BAD 016 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINT MOISE 017 EPP AGNISSANKO III 018 EPV DIALOGUE ET DESTIN 2 019 EPV KAUNAN I 020 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABRAHAM AYEBY 021 EPP GENDARMERIE 022 GROUPE SAINTE FOI ABIDJAN 023 G. S. LES AMAZONES 024 EPV AMAZONES 025 EPP PALMERAIE 026 EPV DIALOGUE 1 028 INSTITUT LES PREMICES 030 COLLEGE GRACE DIVINE 031 GROUPE SCOLAIRE RAIL 4 BAD B ET C 032 EPV DIE MORY 033 EPP SAGBE I (BOKABO) 034 EPP ATCHRO 035 EPV ANOUANZE 036 EPV SAINT PAUL 037 EPP N'SINMON 039 COLLEGE H TAZIEFE 040 EPV LESANGES-NOIRS 041 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSAMOI 045 COLLEGE ANADOR 046 EPV LA PROVIDENCE 047 EPV BEUGRE 048 GROUPE SCOLAIRE HOUANTOUE 049 EPV SAINT-CYR 050 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE JEANNE 051 GROUPE SCOLAIRE SAINTE ELISABETH 052 EPP PLATEAU-DOKUI BAD 054 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE ANNEXE 055 GROUPE SCOLAIRE FENDJE 056 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ABOBOTE 057 EPV CATHOLIQUE SAINT AUGUSTIN 058 GROUPE SCOLAIRE LES ORCHIDEES 059 CENTRE D'EDUCATION PRESCOLAIRE 060 EPV REUSSITE 061 EPP GISCARD D'ESTAING 062 EPP LES FLAMBOYANTS 063 GROUPE SCOLAIRE ASSEMBLEE -

Anthropogenic Activities and the Degradation of the Environmental Quality in Poor Neighborhoods of Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire: Abia Koumassi Village

Journal of Environmental Protection, 2013, 4, 1099-1107 1099 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jep.2013.410126 Published Online October 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/jep) Anthropogenic Activities and the Degradation of the Environmental Quality in Poor Neighborhoods of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: Abia Koumassi Village S. Loko1, K. E. Ahoussi2, Y. B. Koffi2, A. M. Kouassi3, J. Biémi2 1Laboratoire de chimie et de Microbiologie, Université Technologique et Tertiaire Loko (UTTLOKO), Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire; 2Unité de Formation et de Recherche (UFR) des Sciences de la terre et des Ressources Minières (STRM), Université de Cocody, Cocody, Côte d’Ivoire; 3Département des Sciences de la Terre et des Ressources Minières (STeRMi), Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët Boigny (INP-HB), Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire. Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received May 22nd, 2013; revised June 27th, 2013; accepted July 29th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 S. Loko et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT This study deals with the degradation of the quality of the water environment in the village of Abia Koumassi, due to the pollution that has risen in Abidjan. The method used in this study is based on piezometric measurements, the physico-chemical and microbiological analysis. The results were processed using statistical and hydrochemical methods. The groundwater in the village is shallow, with a piezometric average level 0.55 m. The groundwater flows from the north of the village to the south. -

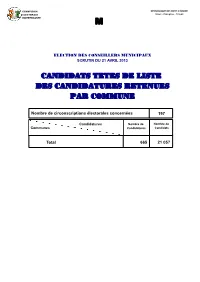

M-Candidats Tetes De Liste Par Commune

COMMISSION REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE ELECTORALE Union - Discipline - Travail INDEPENDANTE M ELECTION DES CONSEILLERS MUNICIPAUX SCRUTIN DU 21 AVRIL 2013 CANDIDATS TETES DE LISTE DES CANDIDATURES RETENUES PAR COMMUNE Nombre de circonscriptions électorales concernées 197 Candidatures Nombre de Nombre de Communes Candidatures Candidats Total 665 21 057 REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE COMMISSION Union - Discipline - Travail ELECTORALE INDEPENDANTE M ELECTION DES CONSEILLERS MUNICIPAUX SCRUTIN DU 21 AVRIL 2013 LISTE DES CANDIDATS TETES DE LISTE PAR COMMUNE N° N° # Commune Candidat Intitulé Liste Groupement Liste Dossier ETTIEN KUMASSI HUMILITE - DISPONIBILITE - 1 027 ABENGOUROU COMMUNE 1 001885 INDEPENDANT DEVELOPPEMENT KABRAN APPIA "ENSEMBLE POUR 2 027 ABENGOUROU COMMUNE 2 001888 INDEPENDANT ABENGOUROU" AMOIKON KOUAKOU BANGA ABENGOUROU, NOTRE 3 027 ABENGOUROU COMMUNE 3 001896 PDCI-RDA AMBITION A TOUS CISSE DAOUDA SALIF VIVRE ENSEMBLE 4 027 ABENGOUROU COMMUNE 4 001899 RDR KONE BRAHIMA BATIR ENSEMBLE 5 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 1 002101 INDEPENDANT LASSANA MEITE ESPOIR POUR LE 6 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 2 002107 INDEPENDANT RENOUVEAU D'ABOBO KONE KIGBAFORY OUSMANE ESPOIR D'ABOBO 7 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 3 002115 INDEPENDANT SOUAGA KOUASSI UNION POUR LE BONHEUR 8 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 4 002116 INDEPENDANT D'ABOBO OUATTARA BRAHIMA UNION ET DEVELOPPEMENT 9 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 5 002210 INDEPENDANT MANDJOBA DIRABOU ALBERIC UNION POUR LE 10 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 6 002219 PDCI-RDA CHANGEMENT TOUNGARA ADAMA VIVRE ENSEMBLE 11 001 ABOBO COMMUNE 7 002580 RDR MAMADOU KANO VIVRE ENSEMBLE -

Côte D'ivoire Country Focus

European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Côte d’Ivoire Country Focus Country of Origin Information Report June 2019 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9476-993-0 doi: 10.2847/055205 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Mariam Dembélé, Abidjan (December 2016) CÔTE D’IVOIRE: COUNTRY FOCUS - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT — 3 Acknowledgements EASO acknowledges as the co-drafters of this report: Italy, Ministry of the Interior, National Commission for the Right of Asylum, International and EU Affairs, COI unit Switzerland, State Secretariat for Migration (SEM), Division Analysis The following departments reviewed this report, together with EASO: France, Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), Division de l'Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches (DIDR) Norway, Landinfo The Netherlands, Immigration and Naturalisation Service, Office for Country of Origin Information and Language Analysis (OCILA) Dr Marie Miran-Guyon, Lecturer at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), researcher, and author of numerous publications on the country reviewed this report. It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. -

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

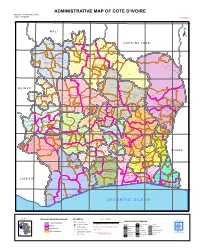

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

Update No. 12 Côte D'ivoire Situation

Update No. 12 Côte d’Ivoire Situation 05 May 2011 HIGHLIGHTS • The inauguration of Mr. Alassane Ouattara as President of Côte d’Ivoire is scheduled to take place on 21 May. • The Ivorian Red Cross reported 60 dead bodies in the Yopougon neighbourhood of Abidjan after ongoing fighting between the “Forces Républicaines de Côte d’Ivoire” and the pro-Gbagbo militias. • On Monday 02 May, Laurent Gbagbo met with the South-African Archbishop, Desmond Tutu alongside former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and former Irish President and UN human rights chief Mary Robinson in Korhogo in the north of Côte d’Ivoire. • The government has started paying civil service salaries, which were on hold during the conflict. • Long queues formed at banks that re-opened on 26 April, after having been closed for two and a half months. Armed robberies of the Banque de l’Habitat de Côte d’Ivoire and Group BNP Paribas vaults were reported on the same day. Community members in Awobo Village, Anyama (Abidjan) met UNHCR, ASAPSU and MESAD at the home of their chief to share the news and express the trauma inflicted upon their community during the period of conflict. (PERHAM S/ UNHCR/29 April 2011). Population Movement Burkina Guinea Sierra Country Guinea Mali Ghana Togo Benin Niger Nigeria Senegal Gambia Faso Bissau Leone Refugees/ Asylum 2,699 107 880 13,508 3,851 239 38 104 41 38 47 10 seekers Liberia 45,729 Ivorian refugees individually registered and 120,192 through the rapid emergency registration. In view of the volatile situation in Côte d’Ivoire, UNHCR is not yet in a position to provide exact figures.