Substance Abuses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Full Report

H U M A N “They Treat Us Like Animals” R I G H T S Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s WATCH Drug Detention Centers “They Treat Us Like Animals” Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s Drug Detention Centers Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0817 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0817 “They Treat Us Like Animals” Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s Drug Detention Centers Map 1: Closed Drug Detention Centers and the Planned National Center .............................. i Map 2: Current Drug Detention Centers in Cambodia .......................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 7 To the Government of Cambodia .............................................................................................. -

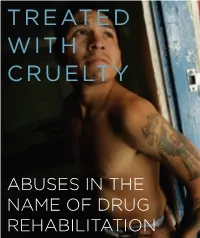

TREATED with CRUELTY: ABUSES in the NAME of DRUG REHABILITATION Remedies

TREATED WITH CRUELTY ABUSES IN THE NAME OF DRUG REHABILITATION Copyright © 2011 by the Open Society Foundations All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For more information, contact: International Harm Reduction Development Program Open Society Foundations www.soros.org/harm-reduction Telephone: 1 212 548 0600 Fax: 1 212 548 4617 Email: [email protected] Cover photo: A heroin user stands in the doorway at the Los Tesoros Escondidos Drug Rehabilita- tion Center in Tijuana, Mexico. Addiction treatment facilities can be brutal and deadly places in Mexico, where better, evidence-based alternatives are rarely available or affordable. (Sandy Huf- faker/ Getty Images) Editing by Roxanne Saucier, Daniel Wolfe, Kathleen Kingsbury, and Paul Silva Design and Layout by: Andiron Studio Open Society Public Health Program The Open Society Public Health Program aims to build societies committed to inclusion, human rights, and justice, in which health-related laws, policies, and practices reflect these values and are based on evidence. The program works to advance the health and human rights of marginalized people by building the capacity of civil society leaders and organiza- tions, and by advocating for greater accountability and transparency in health policy and practice. International Harm Reduction Development Program The International Harm Reduction Development Program (IHRD), part of the Open Society Public Health Program, works to advance the health and human rights of people who use drugs. Through grantmaking, capacity building, and advocacy, IHRD works to reduce HIV, fatal overdose and other drug-related harms; to decrease abuse by police and in places of detention; and to improve the quality of health services. -

1. CAMBODIA 1.1 General Situation 1.1.1 Drug Use There Are No

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 15 April 2014 THE EUROPEAN UNION (OR. en) 8990/14 CORDROGUE 26 ASIE 22 NOTE From: Japanese Regional Chair of the Dublin Group To: Dublin Group No. prev. doc.: 14715/13 Subject: Regional Report on South East Asia and China 1. CAMBODIA 1.1 General situation 1.1.1 Drug use There are no consistent statistics as to the exact number of people who use drugs in Cambodia. However the general consensus among the Royal Government of Cambodia and international agencies is that there are currently between 12,000 and 28,000 people who use drugs. Methamphetamine pills are the most widely used drug in Cambodia, although crystalline methamphetamine is becoming more widely available, with use on the rise, particularly in Phnom Penh and among unemployed youth. Whereas illicit drug use was previously concentrated primarily in urban settings, in recent years it has been expanding into rural areas, in particular in the provinces adjacent to Lao PDR and Thailand (INCSR Cambodia 2012). Drug use among women and within prisons appears to be on the rise (UNODC 2013). 8990/14 JV/fm 1 DG D 2C EN Table 1. Rank of primary drugs of concern in Cambodia, 2008-2012 Drug type 2008 2009 2010** 2011*** 2012**** Methamphetamine pills ● 2* 1 2 2 Crystalline methamphetamine ● 1* 2 1 1 Ecstasy ● ● ● 6 ● Cannabis ● ● 4 4 4 Heroin ● ● 3 5 ● Inhalants ● ● ● 3 3 Opium ● ● ● ● ● ● = Not reported Source(s): *NACD 2010a. **2010 rankings based on DAINAP data and Cambodia country reports. ***NACD 2012b. ****2012 rankings are based on data provided by the National Authority for Combating Drugs. -

UNODC, Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia

Synthetic Drugs in East and Southeast Asia Latest developments and challenges May 2020 Global SMART Programme Copyright © 2020, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNODC would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the Global Synthetic Monitoring: Analyses, Reporting and Trends (SMART) Programme, Laboratory and Scientific Section with the support of the UNODC Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Supervision, direction and review Justice Tettey, Chief, Laboratory and Scientific Section Jeremy Douglas, Regional Representative, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Research and drafting Martin Raithelhuber, Illicit Synthetic Drugs Expert Tun Nay Soe, Inter-regional Programme Coordinator Inshik Sim, Drug Programme Analyst, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Joey Yang Yi Tan, Junior Professional Officer in Drug Research Graphic design and layout Akara Umapornsakula, Graphic Designer Administrative support Jatupat Buasipreeda, Programme Assistant The present report also benefited from the expertise and valuable contributions of UNODC colleagues in the Laboratory and Scientific Section and the Regional Office for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, including Tsegahiwot Abebe Belachew, Rebecca Miller, Reiner Pungs, and John Wojcik. Disclaimer This report has not been formally edited. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNODC or the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Assessment of Compulsory Treatment of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam: an Application of Selected Human Rights Principles

Assessment of compulsory treatment of people who use drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam: An application of selected human rights principles Western Pacific Region WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Assessment of compulsary treatment of people who use drugs in Cambodia, China, Malaysia and Viet Nam: an application of selected human rights principles. 1. Substance abuse, Intravenous - rehabilitation. 2. Substance abuse treatment centers. 3. Human rights. 4. HIV infections – transmission. ISBN 978 92 9061 417 3 (NLM Classification: WM 270) © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. The World Health Organization does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). -

Overview of Drug Situation in Asia: Emerging Concerns

OVERVIEW OF DRUG SITUATION IN ASIA: EMERGING CONCERNS Methamphetamine is the main drug of concern in treatment in Asia. Since the latter part of the 2000s, there has been a strong shift in the drug market in East and South-East Asia, from opiates to methamphetamine; 13 countries in the region reported methamphetamine as their primary drug of concern in 2018 or the latest year available; Annual prevalence of methamphetamine use ranges between 0.5 and 1.1 per cent, which is rather high compared with the global average; 2 OVERVIEW OF DRUG SITUATION IN ASIA: EMERGING CONCERNS South-East Asia emerges as the world’s fastest-growing methamphetamine market; Quantities of methamphetamine seized in East and South-East Asia rose more than eightfold between 2007 and 2017 to 82 tons – 45 per cent of global seizures; In 2017, seizures of methamphetamine tablets in the region amounted to nearly 450 million tablets, a 40% increase compared to the preceding year; Preliminary data for 2018 indicate a further steep increase of seizure to roughly 116 tons; 3 OVERVIEW OF DRUG SITUATION IN ASIA: EMERGING CONCERNS Increased quantities of methamphetamine seizures and decreases in retail prices of the drug in East and South-East Asia suggest that the supply of the drug has expanded; Viet Nam authorities have reported a price of US $ 8,000 for 1 kg of crystalline methamphetamine perceived to have originated from the Golden Triangle in 2017, down from the US $ 13,500 reported in 2016; Transnational organized crime (TOC) groups operating in the region have been increasingly involved in the manufacture and trafficking of methamphetamine and other drugs in the Golden Triangle in recent years; 4 OVERVIEW OF DRUG SITUATION IN ASIA: EMERGING CONCERNS Methamphetamine related treatment admissions account for a large majority of all drug related treatment admissions in the region; This included countries such as Myanmar, who traditionally have a larger proportion of other drug related admissions, other than methamphetamine. -

Pregnant Women and Drugs in Phnom Penh

Advanced Medical Science – International Health (01518) “No need to spend time on them, they are useless” The specific needs, perceptions and vulnerabilities of and surrounding pregnant women who use drugs in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Haylee Rae Walsh (314929) Supervised by Dr Nick Thomson May 2011 WALSH 314929 Abstract This study took place in Phnom Penh, Cambodia and explored the specific needs and perceptions and subsequently the vulnerabilities that pregnant women who use drugs experience in their day-to-day life. Women who use drugs make up 6.5% of all people who use drugs in Cambodia, and NGO Friends-International identified an increase in the number of pregnant women accessing their various programs and services. The study involved 18 participant interviews with women who use(d) drugs during their pregnancy and 21 interviews with key informants from various organisations in Cambodia, conducted in January and February 2011. Oral consent was obtained to preserve the identities of participants and KIs. Thematic analysis of transcripts identified that women who use drugs during pregnancy have needs associated with survival on the street, harm reduction, and reintegration into their community. In addition to these general needs, pregnant women who use drugs also have specific needs concerning their health and that of their unborn child. Stigma in the community and discrimination towards pregnant women who use drugs was also identified. Contributing factors to the vulnerability of women who use drugs during pregnancy were fear of or actual -

“Skin on the Cable”

H U HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH M HUMAN A th N 350 Fifth Avenue, 34 Floor R I New York, NY 10118-3299 G RIGHTS H T S W WATCH A www.hrw.org T C H | J a n u a r “Skin on the Cable” y 2 0 The Illegal Arrest, Arbitrary Detention and Torture of People Who Use Drugs in Cambodia 1 0 In Cambodia, “undesirable” people such as the homeless, beggars, street children and sex workers are often arrested and detained in government centers. “Skin on the Cable” documents the treatment of one such “undesirable” group—people who use drugs—by law enforcement officials and staff working at government drug detention centers. In 2009 there were 11 government detention centers claiming to provide drug “treatment” and “rehabilitation”. These centers hold people rounded up by police or arrested on the request- and payment- of family members. Their detention is without any judicial oversight. In 2008 over 2,300 people were detained in such centers, including many children under 15 and people with mental illnesses. The Cambodia government’s policy of compulsory drug “treatment” in detention centers is both ineffective and abusive. People are detained even if they are not dependent on drugs. The mainstays of "treatment" in such centers are arduous physical exercises and forced labor. Indeed, sweating while exercising or laboring appears to be the most common means to “cure” drug dependence. Compounding the therapeutic ineffectiveness of detention is the extreme cruelty experienced at the hands—and C boots, truncheons and electric batons—of staff in these centers. -

Embargoed: 8 November 2013 - 11H00 ICT (Bangkok) 53 Global SMART Programme 2013

CAMBODIA CAMBODIA Emerging trends and concerns • Transnational and Asian drug trafficking groups continue to target Cambodia as a source, transit and desti- nation country for amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS) and other illicit drugs. • The availability and use of methamphetamine in pill and crystalline form continues to expand. A large and growing majority of persons arrested for drug-related offences or persons submitted for drug treatment in- volve methamphetamine. • Crystalline methamphetamine and cocaine seizures in Cambodia in 2012 are the highest ever reported from the country. Overview of the drug situation There is continued increase in the availability and use of methamphetamine in pill and crystalline form. In The manufacture, trafficking and use of ATS is signifi- 2012, record amounts of crystalline methamphetamine cant and is becoming increasingly problematic in Cam- and cocaine were seized in Cambodia. bodia. Drug law enforcement authorities continue to dismantle a significant number of facilities that illicitly manufacture methamphetamine or produce precursor Patterns and trends of drug use chemicals for the manufacture of methamphetamine and MDMA. In 2012, several ATS manufacturing fa- There are no consistent statistics available on the ex- cilities were dismantled, most of which were located in act number of drug users in Cambodia. In 2012, the Phnom Penh. National Authority for Combating Drugs (NACD) estimated the number of drug users in Cambodia at Transnational organized criminal groups, particularly 4,057.2 However, in March 2013, NACD officials sug- from Asia and West Africa, continue to use Cambodia to gested that the number of drug users was considerably manufacture and transit ATS, their precursor chemicals, higher and likely to be in excess of 10,000.3 In recent and other illicit drugs such as cocaine and heroin. -

Global State HRI 2020 2.1 Asia

Regional Overview 2.1 Asia 63 2.1 ASIA AFGHANISTAN BANGLADESH BHUTAN BRUNEI CAMBODIA CHINA HONG KONG INDIA INDONESIA JAPAN LAOS MACAU MALAYSIA MALDIVES MONGOLIA MYANMAR NEPAL NORTH KOREA PAKISTAN PHILIPPINES SINGAPORE SOUTH KOREA SRI LANKA TAIWAN THAILAND VIETNAM 64 Global State of Harm Reduction 2020 TABLE 2.1.1: Epidemiology of HIV and viral hepatitis, and harm reduction responses in Asia Country/ People who HIV prevalence Hepatitis C Hepatitis B Harm reduction response territory with inject drugs among people (anti-HCV) (anti-HBsAg) reported who inject drugs prevalence prevalence injecting drug (%) among people among Peer use who inject people who NSP1 OAT2 distribution DCRs3 drugs (%) inject drugs of naloxone (%) 139,000 Afghanistan 4.4-20.7[2] 31.2[2] 6.6[2] 24[3] 8[3] [3] x (88,000-190,500)[1] 68,500 Bangladesh 18.1[4] 39.6 - 95[4] 7.0 (4.7-10)[5] 88[6] 7[7] x x (63,500-74,000)[1] Bhutan nk nk nk nk x x x x Brunei nk nk nk nk x x x x Cambodia 4,136 (3,267-4,742)[8] 15.2[8] 30.4[8] nk 5[6] 2[9] x x 1,930,000 China 2.6[11] 29.8 [11] 23.4[5] 814[6] 785[12] x x (1,310,000-2,540,000)[10] Hong Kong 1,078[13] 1.1[14] 56[15] nk[15] x 20[16] x x India 850,000[17] 6.3[10] 40 (33.9-46.1)[5] 4.7 (0.9-.8.5)[5] 266[6] 225[18] [19] x 33,492 Indonesia 28.76-44.5[10][5] 63.5-89.2[10][5] 6.7[10] 215[6] 92[21] x x (14,016-88,812)[20] Japan nk 0.02[10] 40[10] 8.6[10] x x x x Laos 1,600[10] 17.4 (7.8-31.4)[5] nk nk x[23] x[24] x x Macau 189[10] 0[10] 67[10] 17[10] 1[25] 4[25] x x Malaysia 75,000[26] 13.4[26] 67.1[10] nk 501[26] 891[27] x x Maldives 793[10] -

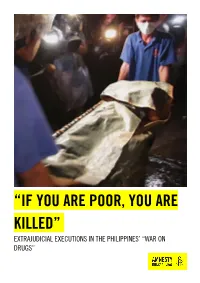

If You Are Poor You Are Killed”: Extrajudicial Executions in The

“IF YOU ARE POOR, YOU ARE KILLED” EXTRAJUDICIAL EXECUTIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES’ “WAR ON DRUGS” Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. Cover photo: The body of one of four men killed by unknown armed persons is taken out of the alleged © Amnesty International 2017 ‘drug den’ where the shootings took place, 12 December 2016, Pasig City, Metro Manila. The case was Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons one of two documented by Amnesty International delegates observing journalists’ night-shift coverage of (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. police activities. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Screengrab, © Amnesty International (photographer Alyx Ayn Arumpac) For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 35/5517/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 9 1. BACKGROUND 10 2. APPLICABLE LAW 13 2.1 INTERNATIONAL LEGAL OBLIGATIONS 13 2.2 NATIONAL FRAMEWORK 15 3. -

Cambodia's Country Report

The 11 th Meeting of the AIPA Fact Finding Committee to Combat the Drug Menace (11 TH AIFOCOM) 12-16 May 2014, Vientiane, Lao PDR CAMBODIA’S COUNTRY REPORT I- INTRODUCTION Since the 90s, cross-border criminal and illegal activities relating to drugs have come into Cambodia’s territory and have increasingly been rising in recent years. Cambodia has therefore suffered from the drug trafficking, distribution and utilization. It has even become recently exposed to drug syndicates who use Cambodia as a drug production site of ATS. II- Drug Situation in Cambodia a. Drug trafficking Cambodia still continues to be affected by the import of drugs from the Golden Triangle, Golden Crescent and Latin America regions. ATS, Heroin has been imported into Cambodia from the Golden Triangle through the northeastern provinces of Cambodia. Besides, Cocaine and Methamphetamine-ice powder have been imported by the international drug criminals from Latin America and Golden Crescent through Phnom Penh and Siem Reap International Airports. Through this import and transit of these drugs, it has been used to supply domestically and export to other countries in the region and other regions by land and water ways and posts. b. Processing and Production of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants (ATS), Plantation and Extraction of Plants Oil. Through cooperation on the suppression of drugs crime, it shows that the drug criminal groups still continue their action to process and produce drugs illegally. In fact, in 2013 competent authorities suppressed a case where it was at the preparation for drugs processing and production through which a lot of the production materials including molds (logo999) and ingredient substances for drugs processing and production were seized in Sankat Toeuk Laok, Khan Tuol Kork, Phnom Penh.