If You Are Poor You Are Killed”: Extrajudicial Executions in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippine Election ; PDF Copied from The

Senatorial Candidates’ Matrices Philippine Election 2010 Name: Nereus “Neric” O. Acosta Jr. Political Party: Liberal Party Agenda Public Service Professional Record Four Pillar Platform: Environment Representative, 1st District of Bukidnon – 1998-2001, 2001-2004, Livelihood 2004-2007 Justice Provincial Board Member, Bukidnon – 1995-1998 Peace Project Director, Bukidnon Integrated Network of Home Industries, Inc. (BINHI) – 1995 seek more decentralization of power and resources to local Staff Researcher, Committee on International Economic Policy of communities and governments (with corresponding performance Representative Ramon Bagatsing – 1989 audits and accountability mechanisms) Academician, Political Scientist greater fiscal discipline in the management and utilization of resources (budget reform, bureaucratic streamlining for prioritization and improved efficiencies) more effective delivery of basic services by agencies of government. Website: www.nericacosta2010.com TRACK RECORD On Asset Reform and CARPER -supports the claims of the Sumilao farmers to their right to the land under the agrarian reform program -was Project Director of BINHI, a rural development NGO, specifically its project on Grameen Banking or microcredit and livelihood assistance programs for poor women in the Bukidnon countryside called the On Social Services and Safety Barangay Unified Livelihood Investments through Grameen Banking or BULIG Nets -to date, the BULIG project has grown to serve over 7,000 women in 150 barangays or villages in Bukidnon, -

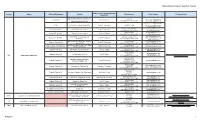

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Download the Full Report

H U M A N “They Treat Us Like Animals” R I G H T S Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s WATCH Drug Detention Centers “They Treat Us Like Animals” Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s Drug Detention Centers Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0817 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0817 “They Treat Us Like Animals” Mistreatment of Drug Users and “Undesirables” in Cambodia’s Drug Detention Centers Map 1: Closed Drug Detention Centers and the Planned National Center .............................. i Map 2: Current Drug Detention Centers in Cambodia .......................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .............................................................................................................. 7 To the Government of Cambodia .............................................................................................. -

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

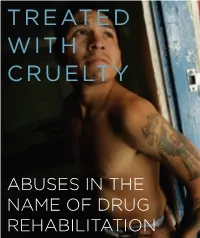

TREATED with CRUELTY: ABUSES in the NAME of DRUG REHABILITATION Remedies

TREATED WITH CRUELTY ABUSES IN THE NAME OF DRUG REHABILITATION Copyright © 2011 by the Open Society Foundations All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form. For more information, contact: International Harm Reduction Development Program Open Society Foundations www.soros.org/harm-reduction Telephone: 1 212 548 0600 Fax: 1 212 548 4617 Email: [email protected] Cover photo: A heroin user stands in the doorway at the Los Tesoros Escondidos Drug Rehabilita- tion Center in Tijuana, Mexico. Addiction treatment facilities can be brutal and deadly places in Mexico, where better, evidence-based alternatives are rarely available or affordable. (Sandy Huf- faker/ Getty Images) Editing by Roxanne Saucier, Daniel Wolfe, Kathleen Kingsbury, and Paul Silva Design and Layout by: Andiron Studio Open Society Public Health Program The Open Society Public Health Program aims to build societies committed to inclusion, human rights, and justice, in which health-related laws, policies, and practices reflect these values and are based on evidence. The program works to advance the health and human rights of marginalized people by building the capacity of civil society leaders and organiza- tions, and by advocating for greater accountability and transparency in health policy and practice. International Harm Reduction Development Program The International Harm Reduction Development Program (IHRD), part of the Open Society Public Health Program, works to advance the health and human rights of people who use drugs. Through grantmaking, capacity building, and advocacy, IHRD works to reduce HIV, fatal overdose and other drug-related harms; to decrease abuse by police and in places of detention; and to improve the quality of health services. -

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines EDITED BY ARIES A. ARUGAY HERMAN JOSEPH S. KRAFT PUBLISHED BY University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies Diliman, Quezon City First Printing, 2020 UP CIDS No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publishers. Recommended Entry: Towards an enhanced strategic policy in the Philippines / edited by Aries A. Arugay, Herman Joseph S. Kraft. -- Quezon City : University of the Philippines, Center for Integrative Studies,[2020],©2020. pages ; cm ISBN 978-971-742-141-4 1. Philippines -- Economic policy. 2. Philippines -- Foreign economic relations. 2. Philippines -- Foreign policy. 3. International economic relations. 4. National Security -- Philippines. I. Arugay, Aries A. II. Kraft, Herman Joseph S. II. Title. 338.9599 HF1599 P020200166 Editors: Aries A. Arugay and Herman Joseph S. Kraft Copy Editors: Alexander F. Villafania and Edelynne Mae R. Escartin Layout and Cover design: Ericson Caguete Printed in the Philippines UP CIDS has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ______________________________________ i Foreword Stefan Jost ____________________________________________ iii Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem _____________________________v List of Abbreviations ___________________________________ ix About the Contributors ________________________________ xiii Introduction The Strategic Outlook of the Philippines: “Situation Normal, Still Muddling Through” Herman Joseph S. Kraft __________________________________1 Maritime Security The South China Sea and East China Sea Disputes: Juxtapositions and Implications for the Philippines Jaime B. -

Psychographics Study on the Voting Behavior of the Cebuano Electorate

PSYCHOGRAPHICS STUDY ON THE VOTING BEHAVIOR OF THE CEBUANO ELECTORATE By Nelia Ereno and Jessa Jane Langoyan ABSTRACT This study identified the attributes of a presidentiable/vice presidentiable that the Cebuano electorates preferred and prioritized as follows: 1) has a heart for the poor and the needy; 2) can provide occupation; 3) has a good personality/character; 4) has good platforms; and 5) has no issue of corruption. It was done through face-to-face interview with Cebuano registered voters randomly chosen using a stratified sampling technique. Canonical Correlation Analysis revealed that there was a significant difference as to the respondents’ preferences on the characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across respondents with respect to age, gender, educational attainment, and economic status. The strength of the relationships were identified to be good in age and educational attainment, moderate in gender and weak in economic status with respect to the characteristics of the presidentiable. Also, there was a good relationship in age bracket, moderate relationship in gender and educational attainment, and weak relationship in economic status with respect to the characteristics of a vice presidentiable. The strength of the said relationships were validated by the established predictive models. Moreover, perceptual mapping of the multivariate correspondence analysis determined the groupings of preferred characteristic traits of the presidential and vice presidential candidates across age, gender, educational attainment and economic status. A focus group discussion was conducted and it validated the survey results. It enumerated more characteristics that explained further the voting behavior of the Cebuano electorates. Keywords: canonical correlation, correspondence analysis perceptual mapping, predictive models INTRODUCTION Cebu has always been perceived as "a province of unpredictability during elections" [1]. -

1. CAMBODIA 1.1 General Situation 1.1.1 Drug Use There Are No

COUNCIL OF Brussels, 15 April 2014 THE EUROPEAN UNION (OR. en) 8990/14 CORDROGUE 26 ASIE 22 NOTE From: Japanese Regional Chair of the Dublin Group To: Dublin Group No. prev. doc.: 14715/13 Subject: Regional Report on South East Asia and China 1. CAMBODIA 1.1 General situation 1.1.1 Drug use There are no consistent statistics as to the exact number of people who use drugs in Cambodia. However the general consensus among the Royal Government of Cambodia and international agencies is that there are currently between 12,000 and 28,000 people who use drugs. Methamphetamine pills are the most widely used drug in Cambodia, although crystalline methamphetamine is becoming more widely available, with use on the rise, particularly in Phnom Penh and among unemployed youth. Whereas illicit drug use was previously concentrated primarily in urban settings, in recent years it has been expanding into rural areas, in particular in the provinces adjacent to Lao PDR and Thailand (INCSR Cambodia 2012). Drug use among women and within prisons appears to be on the rise (UNODC 2013). 8990/14 JV/fm 1 DG D 2C EN Table 1. Rank of primary drugs of concern in Cambodia, 2008-2012 Drug type 2008 2009 2010** 2011*** 2012**** Methamphetamine pills ● 2* 1 2 2 Crystalline methamphetamine ● 1* 2 1 1 Ecstasy ● ● ● 6 ● Cannabis ● ● 4 4 4 Heroin ● ● 3 5 ● Inhalants ● ● ● 3 3 Opium ● ● ● ● ● ● = Not reported Source(s): *NACD 2010a. **2010 rankings based on DAINAP data and Cambodia country reports. ***NACD 2012b. ****2012 rankings are based on data provided by the National Authority for Combating Drugs. -

Demographic Dividend Is Crucial to Philippines' Growth | Cebu Business

THE PHILIPPINE STAR PILIPINO STAR NGAYON THE FREEMAN PANG-MASA BANAT Wed | 11/15/2017 10:59pm | Forex: $1:51.180 Follow Us: The Freeman Metro Cebu Cebu News Region Cebu Business Cebu Lifestyle HoSOUmTH CHINA NEWeSLAB: 31 YEARS OF MOBILE DOWNLOADS EPAPER SEA AMNESIA Demographic dividend is crucial to Philippines’ growth By Carlo S. Lorenciana (The Freeman) | Updated November 14, 2017 - 12:00am LATEST STORIES TRENDING 0 0 googleplus 0 0 Like 0 Bong Go 'surprised, flattered' that selfies went viral CEBU, Philippines — The National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) is urging government November 15, 2017 - 9:01pm agencies and partners to work towards attaining and maximizing the country’s demographic dividend, Iniong steps in for Angela Lee in ONE's which is crucial to the country’s growth. Singapore card November 15, 2017 - 8:45pm The demographic dividend is attained through the transition that takes place when birth and mortality rates decline, and the government is spending less on the needs of the youngest and oldest age groups Review: Not even Wonder Woman can save in the country. This allows a country to use its resources for investment in economic development and 'Justice League' family welfare. November 15, 2017 - 7:32pm Zimbabwe army has President, control of “Maximizing the demographic dividend will ensure that the economy will expand even faster beyond the capital country’s medium-term plan and thus achieve the AmBisyon Natin 2040,” NEDA Undersecretary November 15, 2017 - 6:53pm Rosemarie Edillon said at the recent 2nd National Family Planning Conference held in Waterfront Cebu 14 agreements between China and Philippines City Hotel and Casino. -

![THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7828/the-humble-beginnings-of-the-inquirer-lifestyle-series-fitness-fashion-with-samsung-july-9-2014-fashion-show-667828.webp)

THE HUMBLE BEGINNINGS of the INQUIRER LIFESTYLE SERIES: FITNESS FASHION with SAMSUNG July 9, 2014 FASHION SHOW]

1 The Humble Beginnings of “Inquirer Lifestyle Series: Fitness and Fashion with Samsung Show” Contents Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ................................................................ 8 Vice-Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................... 9 Popes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Board Members .............................................................................................................. 15 Inquirer Fitness and Fashion Board ........................................................................... 15 July 1, 2013 - present ............................................................................................... 15 Philippine Daily Inquirer Executives .......................................................................... 16 Fitness.Fashion Show Project Directors ..................................................................... 16 Metro Manila Council................................................................................................. 16 June 30, 2010 to June 30, 2016 .............................................................................. 16 June 30, 2013 to present ........................................................................................ 17 Days to Remember (January 1, AD 1 to June 30, 2013) ........................................... 17 The Philippines under Spain ...................................................................................... -

Tourism and Crime: Evidence from the Philippines

Kyoto University Tourism and Crime: Evidence from the Philippines Rosalina Palanca-Tan,* Len Patrick Dominic M. Garces,* Angelica Nicole C. Purisima,* and Angelo Christian L. Zaratan* Using panel data gathered from 16 regions of the Philippines for the period 2009–11, this paper investigates the relationship between tourism and crime. The findings of the study show that the relation between tourism and crime may largely depend on the characteristics of visitors and the types of crime. For all types of crime and their aggregate, no significant correlation between the crime rate (defined as the number of crime cases divided by population) and total tourist arrivals is found. However, a statistically significant positive relation is found between foreign tour- ism and robbery and theft cases as well as between overseas Filipino tourism and robbery. On the other hand, domestic tourism is not significantly correlated with any of the four types of crimes. These results, together with a strong evidence of the negative relationship between crime and the crime clearance efficiency, present much opportunity for policy intervention in order to minimize the crime externality of the country’s tourism-led development strategy. Keywords: tourism, crime, negative externality, sustainable development Introduction The tourism industry in the Philippines has expanded rapidly in recent years due primar- ily to intensified marketing of the country’s rich geographical and biological diversity and of its historical and cultural heritage. In 2000–10, the tourism sector consistently made substantial contribution to the Philippine economy, averaging about 5.8% of gross domes- tic product (GDP) on an annual basis. -

1-Listing of the Directors with Attached Resume

CAAP BOARD OF DIRECTORS PROFILE ATTY. ARTHUR P. TUGADE DESIGNATION: Secretary, Department of Transportation Board Chairperson, CAAP Board EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENTS: • Elementary to Law School-cum laude & magna cum laude in Liberal Arts, San Beda College WORK EXPERIENCE: • He founded Perry’s Group of Companies, a corporation that is into trucking, logistics, shipping, fuel distribution, travel, and fashion. • Executive Assistant of the Delgado family’s Transnational Diversified Group Inc. in 1973 and climbed up the ladder to become President and Chief Operating Officer. • Secretary Tugade was appointed President and Chief Executive Officer of the Clark Development Corporation. • 18th Secretary of the Department of Transportation GIOVANNI ZINAMPAN LOPEZ DESIGNATION: Assistant Secretary for Procurement and Project Implementation, Department of Transportation Alternate Board Chairperson, CAAP Board EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENTS: • San Beda College of Law Mendiola, Manila (2001-2006) Ranked 9th of the graduating class • St. Paul University, Tuguegarao City Bachelor of Science in Accountancy Graduated Cum Laude (2000) • Secondary Education St. Louis College of Tuguegarao Batch 1996 • Primary Education Tuguegarao East Central School Batch 1992 • Admitted to the Philippine Bar (2007) with a weighted average of 84.40% • Passed the CPA Board Exams (2000) WORK EXPERIENCE: • Chief of Staff – Office of the Secretary (November 09, 2020 – present) • Assistant Secretary for Procurement and Project Implementation (December 22, 2017 – present) Department of Transportation