Tense, Aspect, Mood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

On Root Modality and Thematic Relations in Tagalog and English*

Proceedings of SALT 26: 775–794, 2016 On root modality and thematic relations in Tagalog and English* Maayan Abenina-Adar Nikos Angelopoulos UCLA UCLA Abstract The literature on modality discusses how context and grammar interact to produce different flavors of necessity primarily in connection with functional modals e.g., English auxiliaries. In contrast, the grammatical properties of lexical modals (i.e., thematic verbs) are less understood. In this paper, we use the Tagalog necessity modal kailangan and English need as a case study in the syntax-semantics of lexical modals. Kailangan and need enter two structures, which we call ‘thematic’ and ‘impersonal’. We show that when they establish a thematic dependency with a subject, they express necessity in light of this subject’s priorities, and in the absence of an overt thematic subject, they express necessity in light of priorities endorsed by the speaker. To account for this, we propose a single lexical entry for kailangan / need that uniformly selects for a ‘needer’ argument. In thematic constructions, the needer is the overt subject, and in impersonal constructions, it is an implicit speaker-bound pronoun. Keywords: modality, thematic relations, Tagalog, syntax-semantics interface 1 Introduction In this paper, we observe that English need and its Tagalog counterpart, kailangan, express two different types of necessity depending on the syntactic structure they enter. We show that thematic constructions like (1) express necessities in light of priorities of the thematic subject, i.e., John, whereas impersonal constructions like (2) express necessities in light of priorities of the speaker. (1) John needs there to be food left over. -

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

Classifiers: a Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J

Western Washington University Western CEDAR Modern & Classical Languages Humanities 3-2002 Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization Edward J. Vajda Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Vajda, Edward J., "Review of: Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Categorization" (2002). Modern & Classical Languages. 35. https://cedar.wwu.edu/mcl_facpubs/35 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Humanities at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern & Classical Languages by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J. Linguistics38 (2002), I37-172. ? 2002 CambridgeUniversity Press Printedin the United Kingdom REVIEWS J. Linguistics 38 (2002). DOI: Io.IOI7/So022226702211378 ? 2002 Cambridge University Press Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald, Classifiers: a typology of noun categorization devices.Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 2000. Pp. xxvi+ 535. Reviewedby EDWARDJ. VAJDA,Western Washington University This book offers a multifaceted,cross-linguistic survey of all types of grammaticaldevices used to categorizenouns. It representsan ambitious expansion beyond earlier studies dealing with individual aspects of this phenomenon, notably Corbett's (I99I) landmark monograph on noun classes(genders), Dixon's importantessay (I982) distinguishingnoun classes fromclassifiers, and Greenberg's(I972) seminalpaper on numeralclassifiers. Aikhenvald'sClassifiers exceeds them all in the number of languages it examines and in its breadth of typological inquiry. The full gamut of morphologicalpatterns used to classify nouns (or, more accurately,the referentsof nouns)is consideredholistically, with an eye towardcategorizing the categorizationdevices themselvesin terms of a comprehensiveframe- work. -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Prosodic Focus∗

Prosodic Focus∗ Michael Wagner March 10, 2020 Abstract This chapter provides an introduction to the phenomenon of prosodic focus, as well as to the theory of Alternative Semantics. Alternative Semantics provides an insightful account of what prosodic focus means, and gives us a notation that can help with better characterizing focus-related phenomena and the terminology used to describe them. We can also translate theoretical ideas about focus and givenness into this notation to facilitate a comparison between frameworks. The discussion will partly be structured by an evaluation of the theories of Givenness, the theory of Relative Givenness, and Unalternative Semantics, but we will cover a range of other ideas and proposals in the process. The chapter concludes with a discussion of phonological issues, and of association with focus. Keywords: focus, givenness, topic, contrast, prominence, intonation, givenness, context, discourse Cite as: Wagner, Michael (2020). Prosodic Focus. In: Gutzmann, D., Matthewson, L., Meier, C., Rullmann, H., and Zimmermann, T. E., editors. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley{Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118788516.sem133 ∗Thanks to the audiences at the semantics colloquium in 2014 in Frankfurt, as well as the participants in classes taught at the DGFS Summer School in T¨ubingen2016, at McGill in the fall of 2016, at the Creteling Summer School in Rethymnos in the summer of 2018, and at the Summer School on Intonation and Word Order in Graz in the fall of 2018 (lectures published on OSF: Wagner, 2018). Thanks also for in-depth comments on an earlier version of this chapter by Dan Goodhue and Lisa Matthewson, and two reviewers; I am also indebted to several discussions of focus issues with Aron Hirsch, Bernhard Schwarz, and Ede Zimmermann (who frequently wanted coffee) over the years. -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> in ROMANCE and ENGLISH

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diego A. de Acosta May 2006 © 2006 Diego A. de Acosta <HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY Diego A. de Acosta, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 Synopsis: At first glance, the development of the Romance and Germanic have- perfects would seem to be well understood. The surface form of the source syntagma is uncontroversial and there is an abundant, inveterate literature that analyzes the emergence of have as an auxiliary. The “endpoints” of the development may be superficially described as follows (for English): (1) OE Ic hine ofslægenne hæbbe > Eng I have slain him The traditional view is that the source syntagma, <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle>, is structured [have [noun participle]], and that this syntagma undergoes change as have loses its possessive meaning. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the traditional view is untenable and readdress two fundamental questions about the development of have-perfects: (i) how is the early ability of have to predicate possession connected with its later role in the perfect?; (ii) what are the syntactic structures and meanings of <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> before the emergence of the have-perfect? With corpus evidence, I show that that the surface string <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> corresponds to three different structures in Old English and Latin; all of these survive into modern English and the Romance languages. -

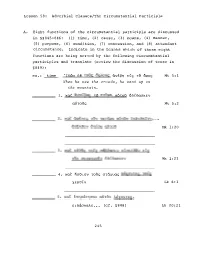

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation.