The Trump Transition and the Afghan War: the Need for Decisive Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF-Dokument

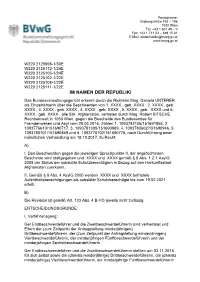

Postadresse: Erdbergstraße 192 – 196 1030 Wien Tel: +43 1 601 49 – 0 Fax: +43 1 711 23 – 889 15 41 E-Mail: [email protected] www.bvwg.gv.at W220 2125098-1/30E W220 2125112-1/24E W220 2125105-1/24E W220 2125102-1/22E W220 2125108-1/22E W220 2125111-1/22E IM NAMEN DER REPUBLIK! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht erkennt durch die Richterin Mag. Daniela UNTERER als Einzelrichterin über die Beschwerden von 1. XXXX , geb. XXXX , 2. XXXX , geb. XXXX , 3. XXXX , geb. XXXX , 4. XXXX , geb. XXXX , 5. XXXX , geb. XXXX und 6. XXXX , geb. XXXX , alle StA. Afghanistan, vertreten durch Mag. Robert BITSCHE, Rechtsanwalt in 1050 Wien, gegen die Bescheide des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl vom 28.03.2016, Zahlen 1. 1093782106/151691055, 2. 1093776610/151690717, 3. 1093781305/151690989, 4. 1093780602/151690946, 5. 1093780101/151690849 und 6. 1093778702/151690776, nach Durchführung einer mündlichen Verhandlung am 19.10.2017, zu Recht: A) I. Den Beschwerden gegen die jeweiligen Spruchpunkte II. der angefochtenen Bescheide wird stattgegeben und XXXX und XXXX gemäß § 8 Abs. 1 Z 1 AsylG 2005 der Status der subsidiär Schutzberechtigten in Bezug auf den Herkunftsstaat Afghanistan zuerkannt. II. Gemäß § 8 Abs. 4 AsylG 2005 werden XXXX und XXXX befristete Aufenthaltsberechtigungen als subsidiär Schutzberechtigte bis zum 19.02.2021 erteilt. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG jeweils nicht zulässig. ENTSCHEIDUNGSGRÜNDE: I. Verfahrensgang: Der Erstbeschwerdeführer und die Zweitbeschwerdeführerin sind verheiratet und Eltern der (zum Zeitpunkt der Antragstellung minderjährigen) Drittbeschwerdeführerin, der (zum Zeitpunkt der Antragstellung minderjährigen) Viertbeschwerdeführerin, der minderjährigen Fünftbeschwerdeführerin und der minderjährigen Sechstbeschwerdeführerin. -

Taliban Narratives

TALIBAN NARRATIVES THOMAS H. JOHNSON with Matthew DuPee and Wali Shaaker Taliban Narratives The Use and Power of Stories in the Afghanistan Conflict A A Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Copyright © Thomas H. Johnson, Matthew DuPee and Wali Shaaker 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Thomas H. Johnson, Matthew DuPee and Wali Shaaker. Taliban Narratives: The Use and Power of Stories in the Afghanistan Conflict. -

Ghani Hails Launch of South Asia Satellite

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:XI Issue No:273 Price: Afs.20 www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes SUNDAY . MAY 07. 2017 -Sawar 17, 1396 HS Ghani hails launch of South Asia Satellite KABUL : President Ashraf Ghani on Friday took part in celebrating the launch of the Indian gifted sat- ellite for South Asia though a vid- eo conference, his office said on Saturday. Ghani congratulated the Indi- an Space Department on the suc- uct,” he told Fox News in an ex- cannot be any other tool,” he went cessful launch of South Asian Sat- clusive interview Wednesday in on. “First, the Daesh comes to ellite, hailing it as a huge step to- Kabul, using the Arabic word for drive people away and then the ward regional cooperation, a state- the extremist Muslim group. “The U.S. comes and drops that big ment from the Presidential Palace Daesh — which is clearly foreign bomb ... come on.” In Karzai’s — emerged in 2015 during the U.S. view, the U.S. simply wants to use said. Indian Prime Minister Naren- presence.” Karzai, who was pres- Afghanistan terrain to “test” its dra Modi, who came to office ident from December 2004 to Sep- toys. “They [America] think this promising stronger relations with tember 2014, said he routinely re- is no man’s land for testing and neighbours such as Sri Lanka, Ne- ceives reports about unmarked he- abuse, but they are wrong about pal and even Pakistan, called the licopters dropping supplies to the that,” he said. -

Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan

ENHANCING SECURITY AND STABILITY IN December 2016 (This page left intentionally blank) Enhancing Security and Stability in Afghanistan December 2016 Report to Congress In Accordance With Section 1225 of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2015 (P.L. 113-291), as amended. Preparation of this report cost the Department of Defense a total of approximately $234,000 in Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017. This includes $22,000 in expenses and $211,000 in labor. Generated on November 3, 2016 Ref ID: 5-C4C5E62 This report is submitted in accordance with Section 1225 of the Carl Levin and Howard P. “Buck” McKeon National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year (FY) 2015 (P.L. 113-291) as amended by Sections 1213 and 1531 of the NDAA for FY 2016 (P.L. 114-92). This report includes a description of the strategy of the United States for enhancing security and stability in Afghanistan, a current and anticipated threat assessment, as well as a description and assessment of the size, structure, strategy, budget, and financing of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces. This report is the fourth in a series of reports required semi- annually through calendar year 2017, and it was prepared in coordination with the Secretary of State. This report describes efforts to enhance security and stability in Afghanistan from June 1 through November 30, 2016. This report complements other reports and information about Afghanistan provided to Congress, and is not intended to be the single source of all information about the combined efforts or the future strategy of the United States, its coalition partners, or Afghanistan. -

Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites the First Half of April 2016

ICT Jihadi Monitoring Group PERIODIC REVIEW Bimonthly Report Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites The First Half of April 2016 International Institute for Counter Terrorism (ICT) Additional resources are available on the ICT Website: www.ict.org.il This report summarizes notable events discussed on jihadist Web forums during the first half of April 2016. Following are the main points covered in the report: The Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan announces the launch of “Operation Omari”, named after Mullah Omar, which is meant to include widespread attacks against enemy posts throughout Afghanistan as well as strikes against enemy commanders in the cities in an effort to liberate Afghanistan from the foreign occupation. According to the organization, its members will establish government systems in the areas under its control, and Afghans serving in enemy ranks will be integrated into the establishment of an Islamic government following negotiations and after they join the ranks of the Emirate. Al-Qaeda, its branches and Salafi-jihadist individuals who support them, eulogize Sheikh Abu Firas al-Suri, a senior Al-Nusra Front leader in Syria who was killed in an American drone strike. Members of the organization vow to continue jihad operations against their enemies until they achieve victory. Al-Shabab Al-Mujahideen, Al-Qaeda’s branch in Somalia, publishes a video documenting an attack by its fighters against a Kenyan army base belonging to the African Union Force in El- Adde in Somalia. According to the organization, over 100 Kenyan soldiers were killed in the attack. The Islamic State publishes documents that it claims prove that it is expanding its operations in the Somali arena. -

EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation

European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security Situation December 2017 SuppORt IS OuR mISSIOn European Asylum Support Office EASO Country of Origin Information Report Afghanistan Security situation December 2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00800 numbers or these calls may be billed. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9494-837-3 doi: 10.2847/574136 © European Asylum Support Office 2017 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © DVIDSHUB (Flickr) Afghan Convoy Attacked Neither EASO nor any person acting on its behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained herein. EASO COI REPORT AFGHANISTAN: SECURITY SITUATION — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge the following national asylum and migration departments as the co-authors of this report: Belgium, Office of the Commissioner General for Refugees and Stateless Persons, Cedoca (Center for Documentation and Research) France, Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless persons (OFPRA), Information, Documentation and Research Division Poland, Country of -

Page 01 May 09.Indd

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESS | 21 SPORT | 29 Ezdan Holding La Liga side set to open Villareal rope in two hotels Qatari striker MONDAY 9 MAY 2016 • 2 SHA’BAAN 1437 • Volume 21 • Number 6791 thepeninsulaqatar @peninsulaqatar @peninsula_qatar El Jaish beat Al Ahli Kuwaiti Emir World Stadium welcomes two Qatari boys Congress to lay QNA KUWAIT: Emir of Kuwait H H Sheikh Sabah Al Ahmad Al Jaber pitch for 2022 Al Sabah welcomed at Bayan Pal- ace yesterday two Qatari boys, Ghanim Mohammad Al Muftah and Ahmad Mohammad Al Muf- come,” said Eng Othman Zarzour, tah and the team of “Ghanim Competition Venues Deputy Exec- Around-the-World Tour”, in the Meeting to bring utive Director at the SC. presence of Kuwait’s Minister of together biggest The summit will host some of the Information and Minister of State biggest names in sports and stadi- for Youth Affairs Sheikh Salman names in sports ums including FIFA, the SC, UEFA, Sabah Salem Al Humoud Al Sabah. and stadiums. DFL Bundesliga and more and act as Ghanim Al Muftah said he a precursor to 2022 FIFA World Cup was honoured to meet the Emir of Qatar. It will outline the best venue Action from El Jaish’s Emir Cup quarter-final clash against Al Ahli at Abdullah Bin Khalifa Stadium Kuwait, adding that his visit came and event security systems. yesterday. El Jaish won 4-2. Earlier in the evening at the same venue, Lekhwiya edged past Al Sailiyah at the invitation of the Kuwaiti The Peninsula “With presentations from gov- 1-0 when Youssef Msakni fired home a late winner in the 87th minute. -

Operation Freedom's Sentinel Report to the United States Congress

LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL FOR OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATION FREEDOM'S SENTINEL REPORT TO THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS OCTOBER 1, 2017‒DECEMBER 31, 2017 LEAD INSPECTOR GENERAL MISSION The Lead Inspector General for Overseas Contingency Operations coordinates among the Inspectors General specified under the law to carry out five primary activities: • Develop a joint strategic plan to conduct comprehensive oversight over the contingency operation. • Ensure independent and effective oversight of programs and operations of the Federal Government in support of the contingency operation through either joint or individual audits, inspections, and investigations. • Promote economy, efficiency, and effectiveness and prevent, detect, and deter fraud, waste, and abuse related to the contingency operation. • Perform analyses to ascertain the accuracy of information provided by federal agencies relating to obligations and expenditures, costs of programs and projects, accountability of funds, and the award and execution of major contracts, grants, and agreements. • Report quarterly and biannually to the Congress and the public on the contingency operation and activities of the Lead Inspector General. (Pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978) FOREWORD We are pleased to submit the Lead Inspector General (Lead IG) quarterly report on Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). This is our 11th quarterly report on this overseas contingency operation in compliance with our individual and collective agency oversight responsibilities pursuant to sections 2, 4, and 8L of the Inspector General Act of 1978. OFS has two complementary missions: 1) the U.S. counterterrorism mission against al Qaeda, the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria-Khorasan, and their affiliates in Afghanistan; and 2) U.S. -

Country of Origin Report on Afghanistan

Country of Origin Report on Afghanistan November 2016 1 Country of Origin Report on Afghanistan November 2016 Edited bij Sub-Saharan Africa Department, The Hague Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. 2 Country of Origin Report on Afghanistan November 2016 Table of contents Table of contents .........................................................................................3 Introduction ................................................................................................5 1 Country information ................................................................................. 7 1.1 Political developments...................................................................................7 1.1.1 Government of National Unity ........................................................................7 1.1.2 Provincial elections.......................................................................................9 1.1.3 Government corruption .................................................................................9 1.2 High Peace Council (HPC) ............................................................................10 1.2.1 Peace talks with the Taliban.........................................................................10 1.3 Power factors ............................................................................................11 1.3.1 Formal power brokers -

KT 9-5-2016 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, MAY 9, 2016 SHAABAN 2, 1437 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Religious Lebanon holds Alvarez KOs Barca, Real co-habitation local elections Khan to retain set up final day brings together amid tight middleweight showdown, all communities3 security 8 WBC16 title Atletico20 beaten Yemen talks struggle as Min 25º Max 39º air strikes shake truce High Tide 01:57 & 12:53 Low Tide Committee talks indefinitely postponed • UN envoy bids to break impasse 07:35 & 20:20 40 PAGES NO: 16868 150 FILS KUWAIT: Yemen’s Houthi movement accused a Saudi- conspiracy theories led coalition of launching air strikes that killed seven people yesterday, shaking a truce that has largely held through more than two weeks of UN-backed peace Well done, London talks in Kuwait. The Iran-allied Houthis and Yemen’s Saudi-backed exiled government are trying to broker a peace through the talks in Kuwait and ease a humani- tarian crisis in the Arabian Peninsula’s poorest country. The year-long conflict has drawn in regional powers and killed at least 6,200 people, according to the United By Badrya Darwish Nations. “The aggressor’s planes bombed various dis- tricts in the Nehm district, leading to the death of seven martyrs and wounding three,” the Houthis said in a statement. Political sources from the Houthi group’s rivals in Yemen’s government say the bombing in the [email protected] Nehm area east of the capital Sanaa was directed at Houthi forces that were massing in the area in violation of a ceasefire that began on April 10.