The Ed of the Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Impressions: James Baroud Horizon Vision Roof Top Tent | Expedition Portal

First Impressions: James Baroud Horizon Vision Roof Top Tent | Expedition Portal EXPEDITION PORTAL FIRST IMPRESSIONS: JAMES BAROUD HORIZON VISION ROOF TOP TENT Light and compact, the newest tent from James Baroud is an innovative approach to tent design. by Christophe Noel Published on December 2nd, 2014 ike many overlanders, there was a time a few years ago when the allure of a roof top tent spurred me to search for the perfect specimen, something that would be quick to set up, offer comfortable sleep, and hopefully endure years of hard use. I thought I found the perfect solution, but the setup proved arduous, the sleep quality so-so, and then there were the host of negative attributes I didn’t fully appreciate at the time of purchase. LMy chief complaint with most roof top tents was relative to weight and collapsed size. Even on my rather large Land Rover Discovery II, most tents sat atop my roof like a pallet of bricks. Even the lighter options tipped the scales at well over 100 pounds, and as an avid backpacker, I just couldn’t believe there wasn’t a lighter more compact alternative, one that could be used on a smaller vehicle if desired. Pundits of the then current offerings were quick to tell me it just wasn’t possible to create such a tent, something I knew couldn’t be true. Fortunately, James Baroud felt the same way. The new James Baroud Horizon Vision is the tent I had been looking for years ago. At 88 pounds it is easily 20 to even 50 pounds lighter than similar tents. -

Canadian Signature Experiences Member List

Last updated November 2019 Member List New member as of May 2019 The National Classification of Services in French was created to inform visitors of the level of service available at tourist sites. There are 3 levels of service: French services at anytime French services upon request Promotional items and/or documentation available in French British Columbia West Coast Overlanding Escape – Hastings Overland The Sea to Sky Experience – Scenic Rush Driving Experiences Desolation Sound Widerness Discovery Cruise – Pacific Coastal Cruises and Tours Hot Springs Cove Excursion – West Coast Aquatic Safaris A Lodge on the Edge of the Rainforest – Farewell Harbour Resort Lodge Experience Life on the Edge: The West Coast Trail – Ecosummer Expeditions Grizzly Bears of the Wild: A First Nations Wildlife Journey into the Great Bear Rainforest – Sea Wolf Adventures Historic Li-Lik-Hel Mine Tour – Copper Cayuse Outfitters The Ultimate Day Tour – Prince of Whales Whale Watching and Marine Adventures A Culinary Tour through Canada’s Desert – Watermark Beach Resort/Covert Farms The Ambassador Guided Tour – Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre Sea Safari in the Fjord of Howe Sound – Sewell’s Marina Wildlife Tracking the Elk River Valley – Strathcona Park Lodge and Outdoor Education Centre Sea Otter Kayak Tour – West Coast Expeditions Gastronomic Gastown Tour – Vancouver Foodie Tours Crystal Hut Fondue by Snowmobile – Canadian Wilderness Adventures The Inside Passage Wilderness Circle Tour – BC Ferries Vacations Sail the Great Bear Rainforest – Bluewater Adventures -

Overlandguide2014.Pdf

This edition published by 4xoverland in 2014 6 The Kippings, Thurlby, Lincolnshire England PE10 0HY +944 (0) 7946 650541 www.4xoverland.com First published as The Complete Guide To Four-Wheel Drive in 1993 in South Africa by International Motoring Productions. 8th edition, 1st imprint. © Andrew St. Pierre White 2014 All rights reserved. Photographs: © Andrew St. Pierre White, unless otherwise indicated Diagrams: © Andrew St. Pierre White, unless otherwise indicated This book and its contents is copyright under the Berne Convention in terms of the Copyright Act (Act 98 of 1978). No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. THOSE OF US LUCKY ENOUGH TO FIND OURSELVES IN THE EARTH’S SECRET PLACES HAVE OUR DEBTS TO PAY. IF WE ABUSE THE ENVIRONMENT WITH OUR 4X4s, OR TAKE FOR GRANTED OUR RIGHT TO GO THERE, ONE DAY THESE RIGHTS WILL BE TAKEN AWAY. Andrew St.Pierre White Andrew St.Pierre White Andrew is one of the world’s most prolific 4x4 and overland writers and film-makers. This book is his 15th on the subject. Born in England, having lived most of his life exploring southern Africa, Andrew’s books, DVDs and TV programmes are known on five continents. His web site, 4xoverland.com, is one of the world’s oldest and busiest dedicated 4x4 web sites. His other professional activity is making TV documentaries and hobbies include flying light aircraft and gliders. -

Industry Trends

LEGISLATIVE ISSUES AFFECTING RV PARKS AND CAMPGROUNDS GROWTH IN OUR INDUSTRY DIGITAL EVOLUTION DRIVING CHANGE SIZE OF THE INDUSTRY POWER OF THE INDUSTRY Outdoor recreation represents 2.2% of US GDP Contributes $734 Billion to the US economy Supports 4.5 million US jobs Source: 2017 US Bureau of Economic Analysis Report ECONOMIC IMPACT $25.6 billion in total economic impact 130k jobs $2 billion paid in local, state and federal taxes LEGISLATIVE ISSUES IN 2020 ADA Website Compliance | Inherent Risk | TIA 1474 ADA WEBSITE COMPLIANCE • WHY is it important? Source: Forbes Magazine ADA WEBSITE COMPLIANCE What can you do? PROTECT YOUR CAMPGROUND! ADA WEBSITE COMPLIANCE ADA WEBSITE COMPLIANCE • Create a link in your footer for “Accessibility” or “ADA Compliance Policy” which drives to a page featuring your policy: • Utilize the ADA Toolkit on Document Library— arvc.org/Document-Library INHERENT RISK • What is it and WHY is it important? INHERENT RISK How to get involved state executive link to ARVC’s contact legislation tracker: arvc.org/Current- 1 information 2 Legislation TIA 1474 TIA 1474 What can you do? •STAY INFORMED •CONTINUE LEARNING •TAKE ACTION GROWTH Profits/Occupancy increasing | Parks expanding/being built | Glamping on the rise PROFITS/OCCUPANCY INCREASING 90% 78% 51% PROFITS OCCUPANCY RATES INCREASED INCREASED INCREASED PARKS EXPANDING/BEING BUILT 44% 27 Parks that reported adding sites in Average number of Sites the past 5 years Added in Past 5 Years 78,253 Approximate New Sites in Past 5 Years PARKS EXPANDING/BEING BUILT 52,169 -

Mindmixer Input Report

1 Topic Name: Where you spend time Idea Title: We love the elk and bison prairie! Idea Detail: Would it be possible to build a wooden observation tower near the areas where the elk and bison are likely to be seen so we could sit outside to watch for them? Idea Author: Sandy L Number of Stars 35 Number of Comments 0 Idea Title: We love Hiking the trails and exploring the forest Idea Detail: LBL offers great hiking opportunities for the family. We love hiking on the trails, exploring the woods, playing in the creeks, and watching the wildlife. Idea Author: Christopher T Number of Stars 31 Number of Comments 0 Address: Woodlands Trce 42055, United States Idea Title: We need more information on the hiking/biking/jeep trails Idea Detail: We know about the main bike trail, but understand there more in the LBL area. We love to ride our bikes, hike and jeep old log roads when we come, but have trouble location info. on all of the trails/roads available for our use. Could you supply more info. on those to the welcome centers? Idea Author: Sandy L Number of Stars 30 Number of Comments 0 Idea Title: Elk and Bison Prairie 2 Idea Detail: Wildlife viewing. Birding. Wildflowers. Idea Author: John P Number of Stars 29 Number of Comments 1 Address: KY-453 42211, United States Comment 1: We buy the 3 pack because we don't always see the Elk. Bison are seen about 60% of the trips and elk about 10%. Wish there was way to increase chance of seeing elk. -

Overlanding the American Southwest by Si Si Penaloza Photography by Douglas Olear

TakeoffTa k e o ff // // C Tr h a a r v t e le r These days, the value of a shift in scenery cannot be overstated. To avoid crowds in National Park campgrounds, I turn to Grand Canyon backcountry options on Hipcamp, a booking app offering up a national network of campsites on private land. Think Airbnb for rural and recreational landowners. Jay-Z’s Marcy Venture Partners and Will Smith’s Dreamers VC have invested in Hipcamp (Series B raise of $25 million led by Andreessen Horowitz, at a valuation of $127 million). Scrolling through options, Sköll Base Camp South Rim had me at hello. The site looked to have ample real estate for the HQ19’s considerable length of 26 feet. On arrival, host Heidi Kaiser emerges from the pinyon pines Birkin in her boho years. The hushed topography of her land fans outlike likea vision, a lotus wearing of relaxation—an a flowing floral idyllic caftan, antidote reminiscent to caffeine of Janeand carbon monoxide. Kaiser has artfully set up hammocks, picnic areas, reading tents, and sculptural vignettes, giving her campsite a deep sense of place. As Douglas sets up the onboard awning, I South Rim. As gruyere melts and mingles with Sauvignon Blanc prep our well-traveled Swissmar fondue set for the first night on We’re camped at the heart of an IDA International Dark Sky Community,over open flame, and stargazing my heart couldn’tmelts at bethe more sight spectacular. of the Milky Way. Overlanding the American Southwest By si si penaloza photography by Douglas Olear here has never been a more meaningful time to make the mode had us sleeping on a queen bed, adorned with a sensual black Waking up in HQ19's high finesse interior feels surreal at journey the primary goal, the reason itself. -

2021-International

2021-International 1 BOILING IS JUST THE BEGINNING You rise before it shines and never fear a headlamp-lit path. Hikes aren’t just reserved for sunny weekends and you’re not traveling because of #wanderlust. No, for JetHeads, adventure is so much more. Aching legs and sore feet be damned, you’re on a mission. A mission to trek farther, climb higher, surf longer and dig deeper. And after a weary, protein bar-filled day on the trail, we know how good a sunset dinner tastes. We’ve also heard the saying that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. That’s why we obsessively engineer and meticulously design our products to boil faster, endure more and give you ultimate backcountry cooking versatility. So whether you’re cheffing up a full spread using our new skillet or rapidly boiling water for morning joe, trust the stove that’s field tested and approved by JetHeads everywhere. 2 3 FAST BOIL SYSTEMS 10 Flash 12 Flash Java Kit 14 Zip PRECISION COOKING SYSTEMS 18 MightyMo 20 MicroMo 22 MiniMo 24 SUMO ACCESSORIES 26 Cookware 28 JetGauge 29 Silicone Coffee Press 30 Hanging Kit & JetSet Utensil Kit 31 JetPower Fuel 32 Spare Cup PRODUCT COMPARISON CHART 34 All Our Stoves In One Spot 4 5 FAST. COMPACT. EFFICIENT. Use Less, Get More—It’s (not) That Simple We’ll spare you the nerdy science jargon and make things simple. We direct every BTU possible toward the cook pot using FluxRing Technology. It helps us harness every possible unit of energy coming from the burner, resulting in highly efficient, lightning-fast boils. -

Northern Trails Safari Make Tracks for Africa

Northern Trails Safari make tracks for Africa This information pack has been put together so that you can prepare for your overland safari. It has been developed over many years of experience overlanding. Please read it carefully. Departure dates for the Northern Trails Depart Cape Town Finish Nairobi Price Local Payment 06 May 2020 17 Jul 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 26 Jun 2020 06 Sep 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 02 Aug 2020 13 Oct 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 27 Aug 2020 07 Nov 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 09 Sep 2020 20 Nov 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 09 Oct 2020 20 Dec 2020 £2,560 US$1,100 30 Oct 2020 10 Jan 2021 £2,560 US$1,100 06 Dec 2020 16 Feb 2021 £2,560 US$1,100 01 Jan 2021 14 Mar 2021 £2,560 US$1,100 16 Jul 2021 26 Sep 2021 £2,560 US$1,100 Countries visited: South Africa • Botswana • Zimbabwe • Zambia • Malawi • Tanzania • Rwanda • Uganda • Kenya Highlights - all departure dates: Cape Town • Robben Island • Cape Point • Shark dive • Cape Agulhas • Ostrich Farm • Cango Caves • Tsitsikamma Forest • Bloukrans Bridge bungee • Blackwater tubing • Port Elizabeth • Addo Elephant National Park • Orange River • Lesotho • The Drakensberg • Johannesburg •Apartheid Museum • Kruger Natonal Park • Khama Rhino Sanctuary • Chobe National Park game drive 1 •Chobe River game cruise • Victoria Falls • Sunset cruise • Whitewater rafting on the Zambezi • Flights over the Falls • Bungee jump • Gorge Swing • Painted Dog Conservation Centre • Hwange National Park • South Luangwa National Park • Lake Malawi • Horse riding • The Rift Valley • Zanzibar Island • Red colobus monkey trek • -

19840304 the Washington Post 4 March 1984

HD Fearless Traveler Overlanding: The Bargain Of Adventure Travel By James T. Yenckel WC 2,022 words PD 4 March 1984 SN The Washington Post SC WP LA English CY (Copyright 1984) LP "Overlanding," a relatively new kind of organized travel that has been popular in Europe for the past two decades, is attracting growing numbers of Americans. Since participants camp instead of staying in hotels, its appeal is to bargain-hunting wanderers with a taste for adventure. The basic idea is that a small group of travelers under the leadership of an experienced guide explores a country (or continent) on a flexible itinerary, going by minibus, full-size coach or -- if the terrain is especially difficult -- by four-wheel-drive truck. The group pitches tents in parks along the way and cooks its own food to cut costs. TD Outfitters in the United States and abroad offer trips as exotic as a five-month London-to-South Africa safari or as close to home as a 12-day jaunt down the Atlantic or Pacific coast. It is one of the cheapest, and friendliest, ways to see large parts of North and South America, Europe, Africa and Asia. Obviously, the traveler must be easy-going, since overlanders spend much of their time together. And, says Pete Fiske, 29, of Allentown, Pa., who has been a Trekamerica guide for four years, they should have stamina, endurance -- and a tolerance for bugs and rainy nights in a tent. Fiske's firm, headquartered in London, has been arranging overland excursions for 12 years in Europe (as Trek Europa) and in the United States, but until this year the trips had been sold primarily to Europeans and other nationalities. -

Make Tracks for Africa This Information Pack Has Been Put Together So That You Can Prepare for Your Overland Tour

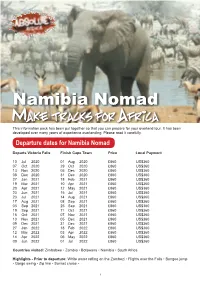

Namibia Nomad Make tracks for Africa This information pack has been put together so that you can prepare for your overland tour. It has been developed over many years of experience overlanding. Please read it carefully. Departure dates for Namibia Nomad Departs Victoria Falls Finish Cape Town Price Local Payment 10 Jul 2020 01 Aug 2020 £860 US$360 07 Oct 2020 29 Oct 2020 £860 US$360 13 Nov 2020 05 Dec 2020 £860 US$360 08 Dec 2020 31 Dec 2020 £860 US$360 27 Jan 2021 18 Feb 2021 £860 US$360 19 Mar 2021 10 Apr 2021 £860 US$360 20 Apr 2021 12 May 2021 £860 US$360 23 Jun 2021 15 Jul 2021 £860 US$360 23 Jul 2021 14 Aug 2021 £860 US$360 17 Aug 2021 08 Sep 2021 £860 US$360 03 Sep 2021 25 Sep 2021 £860 US$360 19 Sep 2021 11 Oct 2021 £860 US$360 16 Oct 2021 07 Nov 2021 £860 US$360 13 Nov 2021 05 Dec 2021 £860 US$360 09 Dec 2021 31 Dec 2021 £860 US$360 27 Jan 2022 18 Feb 2022 £860 US$360 12 Mar 2022 03 Apr 2022 £860 US$360 14 Apr 2022 06 May 2022 £860 US$360 09 Jun 2022 01 Jul 2022 £860 US$360 Countries visited: Zimbabwe • Zambia • Botswana • Namibia • South Africa Highlights - Prior to departure: White water rafting on the Zambezi • Flights over the Falls • Bungee jump • Gorge swing • Zip line • Sunset cruise • 1 Highlights - On Safari: Chobe National Park • Okavango Delta mokoro safari • Flights over the Delta • Bushman visit • Etosha National Park • Africat Carnivore Care • Skeleton Coast • Cape Cross Seal Colony • Swakopmund • Dune quad-biking • Sand-boarding • Tandem skydiving • Horse riding • Township tour • Namib Naukluft National Park • Sossusvlei Dunes • Guided walk on the dunes • Fish River Canyon • Orange River • Stellenbosch • Wine tour • Cape Town Safari structure: Arrive a few days early to enjoy all the fun activities surrounding the Victoria Falls before we head on safari into Botswana’s Chobe National Park and the Okavango Delta, an area of untouched natural beauty. -

22 2020 August Newsletter (Pdf)

8/27/20, 5:11 PM 2020_August_Newsletter Off-Road Safety Academy <[email protected]> Thu 8/27/2020 4:48 PM To: bob.wohlers discoveroffroading.com <[email protected]> Thank you for signing up to receive my newsletters. I hope you’ve found the previous editions informative and helpful for your vehicle- supported adventures. I trust you will enjoy this month’s newsletter. If you have comments, please email me: [email protected]. You can access, download, and read previous newsletters on my website here: NEWSLETTERS Look through the Newsletter Reference for a topic that may interest you, or download them all! Upcoming Four Wheel Camper Death Valley Overland Adventure Tour – October 15-18 https://outlook.office.com/mail/inbox/id/AAQkADg0NWUwMjc3LWUx…tNDI2ZS05ZjUxLTZjNGQ4ZjI0YzI2YgAQAHaDrFT%2Bt5JIuROGJSQ3WjI%3D Page 1 of 15 8/27/20, 5:11 PM There's still time to sign up for this very popular iconic overland Tour. At this moment, there are only SEVEN SPOTS available. This is a not to be missed overlanding-style adventure - each night spent at a different campground. We will visit and camp at some of Death Valley's iconic locations. This tour is ONLY for trucks with Four Wheel Campers on them, trucks with 4WD 4-Low gearing capability, moderate ground clearance, a full-size spare tire, and front and rear frame-mounted recovery points. Once all seven spots are taken, TicketLeap (my ticket and credit card company) will close the Tour. https://outlook.office.com/mail/inbox/id/AAQkADg0NWUwMjc3LWUx…tNDI2ZS05ZjUxLTZjNGQ4ZjI0YzI2YgAQAHaDrFT%2Bt5JIuROGJSQ3WjI%3D Page 2 of 15 8/27/20, 5:11 PM If you have questions after reading all the Tour information on DiscoverOffRoading.com, please call Bob at: 909.844.2583. -

Desert Explorer NCS + Dossier + Predepinfo

DESERT EXPLORER – CAMPING Tag 1 Südafrika - Cederberg Mountain Region Sie verlassen Kapstadt und es gibt einen letzten Foto Stopp in Table View für einen spektakulären Panoramablick auf den Tafelberg. Ihr weiterer Weg führt Sie in die Cederberg Region, wo Sie eine geführte Wanderung machen, nachdem die Zelte aufgebaut sind. Auf Ihrer Wanderung durch die Berge erfahren Sie mehr über die einheimischen Pflanzen, Tiere und einige Felsmalereien. Am späten Nachmittag wird Ihnen ihr Reiseleiter eine ausführliche Einweisung für die Tour geben. Mahlzeiten: Mittagessen, Abendessen Tag 2 Namaqualand - Gariep (Orange) River Nach einem frühen Start geht es in Richtung Norden über Springbok. Diese Region ist bekannt für Diamanten, Kupfer und zum Frühjahr für ihre Blumenpracht. Das Camp befindet sich direkt an dem Flussufer, das die Grenze zwischen Südafrika und Namibia bildet. Wenn der Strom nicht zu stark ist, können Sie nach Namibia schwimmen, aber Sie müssen wieder kommen und Ihren Pass abstempeln lassen, wenn Sie beabsichtigen, weiter durch das Land zu reisen! Mahlzeiten: Frühstück, Mittagessen, Abendessen Tag 3 Namibia - Gariep (Orange) River - Fish River Canyon An diesem Morgen gibt es die Chance, das schöne Tal des Flusses mit dem Kanu zu erleben oder einfach nur im Camp zu entspannen. Nach dem Mittagessen überqueren Sie die Grenze und reisen zum Fish River Canyon. Nach einem schönen Spaziergang entlang der Kante des Canyons genießen Sie Ihr Abendessen, während Sie den Sonnenuntergang beobachten. Optionale Aktivitäten: halber Tag Kanu-Abenteuer. Mahlzeiten: Frühstück, Mittagessen, Abendessen Tag 4 Namib-Naukluft-Nationalpark Sie kommen in den Namib-Naukluft-Nationalpark und nachdem das Camp eingerichtet ist, genießen Sie eine kurze Wanderung in dem Sesriem Canyon.