Thesis Constructing the Polar World: the German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Landscapes of Exploration' Education Pack

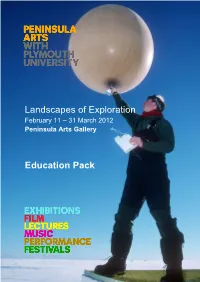

Landscapes of Exploration February 11 – 31 March 2012 Peninsula Arts Gallery Education Pack Cover image courtesy of British Antarctic Survey Cover image: Launch of a radiosonde meteorological balloon by a scientist/meteorologist at Halley Research Station. Atmospheric scientists at Rothera and Halley Research Stations collect data about the atmosphere above Antarctica this is done by launching radiosonde meteorological balloons which have small sensors and a transmitter attached to them. The balloons are filled with helium and so rise high into the Antarctic atmosphere sampling the air and transmitting the data back to the station far below. A radiosonde meteorological balloon holds an impressive 2,000 litres of helium, giving it enough lift to climb for up to two hours. Helium is lighter than air and so causes the balloon to rise rapidly through the atmosphere, while the instruments beneath it sample all the required data and transmit the information back to the surface. - Permissions for information on radiosonde meteorological balloons kindly provided by British Antarctic Survey. For a full activity sheet on how scientists collect data from the air in Antarctica please visit the Discovering Antarctica website www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk and select resources www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk has been developed jointly by the Royal Geographical Society, with IBG0 and the British Antarctic Survey, with funding from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) supports geography in universities and schools, through expeditions and fieldwork and with the public and policy makers. Full details about the Society’s work, and how you can become a member, is available on www.rgs.org All activities in this handbook that are from www.discoveringantarctica.org.uk will be clearly identified. -

Our Arctic Nation a U.S

Connecting the United States to the Arctic OUR ARCTIC NATION A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative Cover Photo: Cover Photo: Hosting Arctic Council meetings during the U.S. Chairmanship gave the United States an opportunity to share the beauty of America’s Arctic state, Alaska—including this glacier ice cave near Juneau—with thousands of international visitors. Photo: David Lienemann, www. davidlienemann.com OUR ARCTIC NATION Connecting the United States to the Arctic A U.S. Arctic Council Chairmanship Initiative TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Alabama . .2 14 Illinois . 32 02 Alaska . .4 15 Indiana . 34 03 Arizona. 10 16 Iowa . 36 04 Arkansas . 12 17 Kansas . 38 05 California. 14 18 Kentucky . 40 06 Colorado . 16 19 Louisiana. 42 07 Connecticut. 18 20 Maine . 44 08 Delaware . 20 21 Maryland. 46 09 District of Columbia . 22 22 Massachusetts . 48 10 Florida . 24 23 Michigan . 50 11 Georgia. 26 24 Minnesota . 52 12 Hawai‘i. 28 25 Mississippi . 54 Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. Photo: iStock.com 13 Idaho . 30 26 Missouri . 56 27 Montana . 58 40 Rhode Island . 84 28 Nebraska . 60 41 South Carolina . 86 29 Nevada. 62 42 South Dakota . 88 30 New Hampshire . 64 43 Tennessee . 90 31 New Jersey . 66 44 Texas. 92 32 New Mexico . 68 45 Utah . 94 33 New York . 70 46 Vermont . 96 34 North Carolina . 72 47 Virginia . 98 35 North Dakota . 74 48 Washington. .100 36 Ohio . 76 49 West Virginia . .102 37 Oklahoma . 78 50 Wisconsin . .104 38 Oregon. 80 51 Wyoming. .106 39 Pennsylvania . 82 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE AN ARCTIC NATION? oday, the Arctic region commands the world’s attention as never before. -

Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion

Chapter 3 Adam of Bremen on Slavic Religion 1 Introduction: Adam of Bremen and His Work “A. minimus sanctae Bremensis ecclesiae canonicus”1 – in this humble manner, Adam of Bremen introduced himself on the pages of Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum, yet his name did not sink into oblivion. We know it thanks to a chronicler, Helmold of Bosau,2 who had a very high opinion of the Master of Bremen’s work, and after nearly a century decided to follow it as a model. Scholarship has awarded Adam of Bremen not only with a significant place among 11th-c. writers, but also in the whole period of the Latin Middle Ages.3 The historiographic genre of his work, a history of a bishopric, was devel- oped on a larger scale only after the end of the famous conflict on investiture between the papacy and the empire. The very appearance of this trend in histo- riography was a result of an increase in institutional subjectivity of the particu- lar Church.4 In the case of the environment of the cathedral in Bremen, one can even say that this phenomenon could be observed at least half a century 1 Adam, [Praefatio]. This manner of humble servant refers to St. Paul’s writing e.g. Eph 3:8; 1 Cor 15:9, and to some extent it seems to be an allusion to Christ’s verdict that his disciples quarrelled about which one of them would be the greatest (see Lk 9:48). 2 Helmold I, 14: “Testis est magister Adam, qui gesta Hammemburgensis ecclesiae pontificum disertissimo sermone conscripsit …” (“The witness is master Adam, who with great skill and fluency described the deeds of the bishops of the Church in Hamburg …”). -

Tides-Of-The-Desert.Pdf

UNIVERSITÄT ZU KÖLN Heinrich -Barth -Institut für Archäologie und Geschichte Afrikas 14 A F R I C A P R A E H I S T O R I C A Monographien zur Archäologie und Umwelt Afrikas Monographs on African Archaeology and Environment Monographies sur l'Archéologie et l'Environnement d'Afrique Herausgegeben von Rudolph Kuper KÖLN 2002 Tides of the Desert – Gezeiten der Wüste Contributions to the Archaeology and Environmental History of Africa in Honour of Rudolph Kuper Beiträge zu Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte Afrikas zu Ehren von Rudolph Kuper Edited by Jennerstrasse 8 Jennerstrasse 8 comprises Tilman Lenssen-Erz, Ursula Tegtmeier and Stefan Kröpelin as well as Hubert Berke, Barbara Eichhorn, Michael Herb, Friederike Jesse, Birgit Keding, Karin Kindermann, Jörg Linstädter, Stefanie Nußbaum, Heiko Riemer, Werner Schuck and Ralf Vogelsang HEINRICH-BARTH-INSTITUT © HEINRICH-BARTH - INSTITUT e.V., Köln 2001 Jennerstraße 8, D – 50823 Köln http://www.uni-koeln.de/hbi/ Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Reproduktionen jeglicher Art nur mit ausdrücklicher Genehmigung. CIP – Titelaufnahme der Deutschen Bibliothek Tides of the desert : contributions to the archaeolo- gy and environmental history of Africa in honour of Rudolph Kuper = Gezeiten der Wüste : Beiträge zu Archäologie und Umweltgeschichte Afrikas zu Ehren von Rudolph Kuper / Heinrich-Barth-In- stitut. Ed. by Jennerstrasse 8. - Köln : Heinrich- Barth-Inst., 2002 (Africa praehistorica ; 14) ISBN 3-927688-00-2 Printed in Germany Druck: Hans Kock GmbH, Bielefeld Typographisches Konzept: Klaus Kodalle Digitale Bildbearbeitung: Jörg Lindenbeck Satz und Layout: Ursula Tegtmeier Titelgestaltung: Marie-Theres Erz Redaktion: Jennerstrasse 8 Gesetzt in Palatino ISSN 0947-2673 Contents Prolog Jennerstrasse 8 – The Editors Eine Festschrift für Rudolph Kuper.......................... -

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

E:\Teksty\2016 Teksty\PH 4 2015\Wersja Elektroniczna

PRZEGLĄD HUMANISTYCZNY 4, 2015 Florian Krobb (National University of Ireland Maynooth) FROM TRACK TO TERRITORY: GERMAN CARTOGRAPHIC PENETRATION OF AFRICA, C. 1860–1900 I On page 130, the Cambridge History Atlas juxtaposes two maps of Africa. The larger, page-filling map shows the African continent’s political division in the first decade of the twentieth century: apart from Morocco, Liberia and Abyssinia, the entire landmass and all adjacent islands are shaded in the cha- racteristic colours of their European owners. Geographical features, mountains, rivers and the names of those features which do not lend themselves to graphic representation, such as the Kalahari Desert, appear very much subordinate to the bold reds, yellows and blues of the European nations. History, at the beginning of the twentieth century, is the development of nation states, and Africa had been integrated into its trajectory by being partitioned into dependencies of those very nation states. The Atlas integrates itself into, on the eve of the First World War even represents a pinnacle of, the European master narrative of the formation of nations, their expansion beyond domestic borders in the process of colonisation, the consolidation of these possessions into global empires, and the vying for strategic advantage and dominance on the global stage in imperialist fashion. On the inset in the bottom left corner, the same geographical region is depicted as it was in the year 1870. The smaller size leaves even less room for geographical information: some large rivers and lakes are marked in the white expanse that is only partly surrounded by thin strips of land shaded in the European nations’ identifying colours. -

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Representations of Antarctic Exploration by Lesser Known Heroic Era Photographers

Filtering ‘ways of seeing’ through their lenses: representations of Antarctic exploration by lesser known Heroic Era photographers. Patricia Margaret Millar B.A. (1972), B.Ed. (Hons) (1999), Ph.D. (Ed.) (2005), B.Ant.Stud. (Hons) (2009) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science – Social Sciences. University of Tasmania 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. ………………………………….. ………………….. Patricia Margaret Millar Date ii Abstract Photographers made a major contribution to the recording of the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. By far the best known photographers were the professionals, Herbert Ponting and Frank Hurley, hired to photograph British and Australasian expeditions. But a great number of photographs were also taken on Belgian, German, Swedish, French, Norwegian and Japanese expeditions. These were taken by amateurs, sometimes designated official photographers, often scientists recording their research. Apart from a few Pole-reaching images from the Norwegian expedition, these lesser known expedition photographers and their work seldom feature in the scholarly literature on the Heroic Era, but they, too, have their importance. They played a vital role in the growing understanding and advancement of Antarctic science; they provided visual evidence of their nation’s determination to penetrate the polar unknown; and they played a formative role in public perceptions of Antarctic geopolitics. -

German Exploration of the Polar World: a History, 1870–1940, by David T. Murphy

394 • REVIEWS the derived surnames are Scandinavian. Following each VARJOLA, P. 1990. The Etholén Collection: The ethnographic of these three divisions is a long list of names. In Madsen’s Alaskan collection of Adolf Etholén and his contemporaries in home, the women spoke English and Russian, and the men the National Museum of Finland. Helsinki: National Board of spoke English, various European languages, and some- Antiquities. times multiple Native languages, raising questions (espe- cially when combined with essays by Jeff Leer and Lydia Karen Wood Workman Black) about multilingualism in the past. In what situa- 3310 East 41st Avenue tions were which language(s) used, and by whom? Multi- Anchorage, Alaska, U.S.A. ple language use is a foreign concept to many Americans, 99508 and perhaps we pay too little attention to its possibilities. So many people are involved in this volume that no one person using it could know all of them. One deficit is that GERMAN EXPLORATION OF THE POLAR WORLD: the essays have only self-identification of the authors. A HISTORY, 1870–1940. By DAVID T. MURPHY. Lin- This is also and more expectably the case of the nine coln, Nebraska, and London: University of Nebraska Alutiiq Elders in the final chapter, although there is a Press, 2002. ISBN 0-8032-3205-5. xii + 273 p., maps, listing of Alutiiq Elders, their places of birth and present b&w illus., notes, bib., index. Hardbound. US$49.95; residences (xi–xii), and the three editors are given very UK£37.95. brief biographical sketches (p. 265). A list of contributors would have been helpful. -

Influences of German Science and Scientists on Melbourne Observatory

CSIRO Publishing The Royal Society of Victoria, 127, 43–58, 2015 www.publish.csiro.au/journals/rs 10.1071/RS15004 INFLUENCES OF GERMAN SCIENCE AND SCIENTISTS ON MELBOURNE OBSERVATORY Barry a.J. Clark Astronomical Society of Victoria Inc. PO Box 1059, GPO Melbourne 3001 Correspondence: Barry Clark, [email protected] ABSTRACT: The multidisciplinary approach of Alexander von Humboldt in scientific studies of the natural world in the first half of the nineteenth century gained early and lasting acclaim. Later, given the broad scientific interests of colonial Victoria’s first Government Astronomer Robert Ellery, one could expect to find some evidence of the Humboldtian approach in the operations of Williamstown Observatory and its successor, Melbourne Observatory. On examination, and without discounting the importance of other international scientific contributions, it appears that Melbourne Observatory was indeed substantially influenced from afar by Humboldt and other German scientists, and in person by Georg Neumayer in particular. Some of the ways in which these influences acted are obvious but others are less so. Like the other Australian state observatories, in its later years Melbourne Observatory had to concentrate its diminishing resources on positional astronomy and timekeeping. Along with Sydney Observatory, it has survived almost intact to become a heritage treasure, perpetuating appreciation of its formative influences. Keywords: Melbourne Observatory, 19th century, Neumayer, German science The pioneering holistic approach of Alexander von (Geoscience Australia 2015). In 1838 Carl Friedrich Gauss Humboldt in his scientific expeditions to study the natural helped put Humboldt’s call into practice by setting up world had a substantial, lasting and international influence the Göttinger Magnetische Verein (Göttingen Magnetic on a broad range of scientific fields. -

Geography in Higher Education in the UK NOT to BE CITED WITHOUT

Geography in Higher Education in the UK J D SIDAWAY* and R J JOHNSTON** 1 * Department of Geography, Loughborough University, Loughborough, Leicestershire, LE11 3TU, UK ** School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1SS, UK This paper was invited for a special issue of Journal of Geography in Higher Education NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT THE AUTHORS’ PERMISSION ABSTRACT Geography is firmly established as a separate discipline within British higher education, a position founded on its strength in the country’s school system throughout the twentieth century. This position has enabled the discipline to prosper and it has been at the core of many intellectual developments. With changes in the nature of universities, however, that position has increasingly to be rethought. KEY WORDS: Geography, United Kingdom British geography’s emerging place Geography as a subject has a long history in the UK, but it was only clearly recognised as a separate academic discipline at the end of the nineteenth century. Before that, elements of geography were taught in the country’s universities and there was a short-lived appointment of a Professor at University College London in the 1830s – the decade that also saw the foundation of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). But it was in the country’s schools that the foundations of the academic discipline were laid. Officers of the RGS identified a need for geography to be taught there, as part of the formation of an educated citizenry, for whom knowledge about the world – and, especially, of Britain’s position at the centre of the largest empire within that world – was deemed necessary.