Level 1 Coaching Course Pre-Course Reading Material Please Complete and Bring to the Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2016/17 Contents Chair Foreword

Annual Report 2016/17 Contents Chair Foreword Chair Foreword 3 I am so proud to be the Chair of Welsh Netball, this resilient organisation capable of real change. CEO Report 4 This year has seen the organisation progress from a position of stability to one of active growth. Community Development 6 Our connectivity across the world of sport has visibly increased, Wendy B White BEM 14 demonstrated most notably by the Swansea University International Catherine Lewis Test Series v Silver Ferns in February. A huge undertaking indeed, Performance 15 Chair of Welsh Netball but one that has placed netball firmly on the map and ensured that the voice of Welsh Netball is now heard globally as well as across Europe. The Swansea University International Test Series 24 Welsh Netball’s workforce remains active across the country with Celtic Dragons 28 participation increasing across members, officials and coaches. Our dedicated family of volunteers continue to support netball on every Communications 32 level, allowing women and girls to participate from their very first steps onto court. We are very thankful for their time and endless efforts. Our family of sponsors also continues to grow as more and more partners recognise the impact and importance of women’s sport. Their support and resources power our squads, improving performance and allowing our players more ways to engage with the wider sporting audience. Many thanks to the Welsh Netball Board for their unwavering support. All volunteers, they give their time and effort willingly. Also to our staff, your commitment and resourcefulness has been clearly demonstrated this year and we thank you for always going the extra mile. -

Annual Report 2018-19

Annual Report 2018-19 i CONTENTS 01 2018-19 Highlights 02 CEO and Chairman’s Statements 04 Participation 06 Coaching 08 Officiating 10 Goalden Globe Awards 12 Vitality Roses 14 Performance Pathway 16 Vitality Netball World Cup 2019 18 Vitality Netball Superleague 20 Community Competition 22 Membership 24 Commercial and Marketing 28 Governance, Compliance and Inclusion 29 Heritage 30 Regions 32 Financial Review Vitality Roses VNWC2019/international photos and Vitality Netball Superleague Winners photo: Getty Images ii 2018-19 HIGHLIGHTS Commonwealth Games GOLD medallists England Netball crowned Sports Organisation of the Year at the BT Sport Industry Awards Vitality Roses awarded Team of the Year and Greatest Sporting Moment at the BBC Sports Personality of the Year Awards Vitality Roses ranked 2nd in INF World Rankings Significant reduction in reliance on public funding with 50.4% of revenue generated from our own sources, a real term increase of £1.1m from 2017-18 Back to Netball 10 year anniversary 100k Back to Netball participants 1,403 Walking Netball participants from the Women’s Institute 5,506 students engaged in the UNO programme 1,200+ deaf and disabled participants Over 900 new Level 1 and Level 2 coaches qualified 655 new official qualifications 33 players selected for the Roses Academy programme 106 grants awarded for athletes through Backing the Best, SportsAid, TASS and DiSE Vitality announced as title sponsor of the Vitality Netball World Cup 2019 Sky Sports and BBC confirmed as UK broadcast partners for the Vitality Netball World Cup 2019 500 “Pivoteers” recruited for the Vitality Netball World Cup 2019 Over 100k members for the fourth year running Partnerships signed with Vitality, Jaffa Fruit, Nike, Gilbert, Red Bull, The British Army, Elastoplast and Oasis iv 1 CEO AND CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENTS 2018-19 has been one of the biggest and most exciting years for England Colin Povey The Board has continued To top all of this off we have been Chairman of England Netball to maintain best practice in preparing for the Vitality Netball Netball to date. -

La Federación Internacional De Netball

LA FEDERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL DE NETBALL PAUTAS PARA ESTABLECER UNA ASOCIACIÓN DE NETBALL NUEVA: COMPONENTES BÁSICOS DE UNA CONSTITUCIÓN Introducción El netball es el principal deporte femenino en equipo y mediante la creciente participación, los eventos destacados y la búsqueda de la excelencia en la organización aspira a ser uno de los deportes en equipo más populares y excitantes. La Federación Internacional de Netball (INF, International Netball Federation) lidera el desarrollo del deporte en todo el mundo y sus miembros son las Asociaciones Nacionales de Netball de aquellos países donde el deporte es jugado y está organizado. La INF le da la bienvenida a aquellos individuos o entidades que expresen su interés por establecer una asociación nacional de netball con el objeto de desarrollar este deporte en su país. Cada asociación nacional nueva deberá contar con un documento constituyente que establezca los principios según los cuales la asociación será organizada y gobernada. El documento constituyente deberá tomar en cuenta los intereses de la asociación, de sus miembros y de la comunidad a la cual la asociación brindará sus servicios. Deberá también cumplir con la ley nacional del país en el cual la asociación será establecida. Aquellos que deseen establecer una asociación nacional de netball necesitarán elegir la forma legal apropiada para que dicha asociación adopte (por ejemplo: una asociación sin personería jurídica, una sociedad limitada por garantía, una sociedad de responsabilidad limitada, una asociación benéfica registrada, etc.1). La forma legal de la asociación determinará el tipo de documento constituyente que se requiere y también la estructura de la asociación. Generalmente, una asociación nacional de netball es organizada como una entidad sin fines de lucro y los ingresos de la asociación se usan para administrar las actividades de la organización y apoyar y desarrollar el deporte en toda la nación. -

Netball Shines in Glasgow a Round-Up of the Commonwealth Games 2014

The Official Quarterly Newsletter of the International Netball Federation November 2014 netballnews world inside FAST5 Action in Auckland We preview Netball World Series 2014 Netball's Rapid Rise in Asia New countries joining the netball family Netball Shines Netball World Cup 2015 in Glasgow Sixteen teams are on their way to Sydney netball.org | 1 IFNA Mag Spread July 2014_Layout 1 26/06/2014 16:39 Page 1 GILBERT NETBALL proud sponsors of the international netball federation Gilbert Netball is the only truly global Netball brand. Teamwear The Gilbert netball teamwear range offers We sell products in every Netball playing country a combination of high-performance fabrics around the world and assist the development of in conjunction with a comfortable and the game by developing links in countries where functional fit to meet a player’s match and Netball is emerging. training kit requirements at every level. We are proud to be the Official and Exclusive Clothing Suppliers to the IUA (International Netball Federation’s Umpires) and the Barbados, Botswana, Jamaica, Malawi, For a full listing of our Official Distributors Scotland, Trinidad and Tobago Netball Federations. We are also the exclusive clothing supplier Please visit www.gilbert-netball.com to Manchester Thunder and Yorkshire Jets UK Superleague teams. or visit our online merchandising store at www.netballshop.org BALL SUPPLIERS http://www.facebook.com/GILBERTNETBALL We are proud to be the official and Exclusive Ball Suppliers to the INF (International Netball Federation) as well as Argentina, Australia, Barbados, Botswana, Proud to be a Canada, Jamaica, Malawi, New Supporter of Zealand, Scotland, St. -

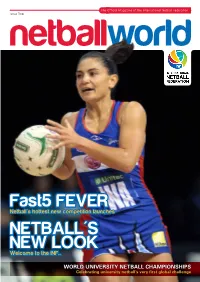

Fast5 FEVER NETBALL's NEW LOOK

The Official Magazine of the International Netball Federation Issue Two netballworld Fast5 FEVER Netball's hottest new competition launches NETBALL'S NEW LOOK Welcome to the INF... WORLD UNIVERSITY NETBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS Celebrating university netball’s very first global challenge IFNA Mag Spread.qxd_Layout 1 24/10/2012 15:04 Page 1 GILBERT NETBALL proud sponsors of the international netball federation Gilbert Netball is the only truly global Netball brand. Teamwear The Gilbert netball teamwear range offers We sell products in every Netball playing country a combination of high-performance fabrics around the world and assist the development of in conjunction with a comfortable and the game by developing links in countries where functional fit to meet a player’s match and Netball is emerging. training kit requirements at every level. We are proud to be the Official and Exclusive Clothing Suppliers to the IUA (International Netball Federation’s Umpires) and the Barbados, Botswana, Jamaica, Malawi, For a full listing of our Official Distributors Scotland, Trinidad and Tobago Netball Federations. We are also the exclusive clothing supplier Please visit www.gilbert-netball.com to Manchester Thunder and Yorkshire Jets UK Superleague teams. or visit our online merchandising store at www.gilbert-netball.com/inf BALL SUPPLIERS http://www.facebook.com/GILBERTNETBALL We are proud to be the official and Exclusive Ball Suppliers to the INF (International Netball Federation) as well as Argentina, Australia, Barbados, Botswana, Canada, Israel, Jamaica, Malawi, New Zealand, Nigeria, Scotland, St. Lucia, Tanzania, Trinidad and Tobago, USA and Wales. Customised luggage and OTHER products are also available upon request. -

Annual Report 2017/18 Contents

Annual Report 2017/18 Contents Chair Foreword 3 CEO Summary 4 Community Development 6 Performance 17 Communications 26 Celtic Dragons 28 Acknowledgements 29 2 www.welshnetball.com Chair Foreword Another year of my tenure has passed as Chair of Welsh Netball and I remain proud of the organisation as it continues to stabilise and grow in a tough economic climate. The performance of the Home Countries at this year’s Commonwealth Games showed the world the power of netball and female empowerment through the medium of sport. All four UK countries showed what they can do within the limits of funding available to them. The professionalism Catherine Lewis of the sport at the elite level and England winning the gold illustrates that Chair of Welsh Netball female team sport athletes given the chance to train, eat and sleep as full- time professionals, will deliver. That is what Welsh Netball aspires for its elite arm of the game and now more than ever the links that we Can seCure with commercial sponsorship and assistance is the key to the progression of the performance side of our beautiful sport. Our national squads, Celtic Flames and Celtic Dragons have represented Wales on the world stage over the course of the last year and whilst they have been highs and lows, that’s sport and we are justifably proud of our players, coaches, team managers, umpires and whole army of volunteers who make this sport tiCk. I wish to thank all those past and present who have supported and sculpted these squads and we thank you for what you have given to our sport. -

“Gateway to the Sideline”: Brand Communication on Social Media at Large-Scale Sporting Events

“GATEWAY TO THE SIDELINE”: BRAND COMMUNICATION ON SOCIAL MEDIA AT LARGE-SCALE SPORTING EVENTS Portia Vann Bachelor of Media and Communication (Hons.), Bachelor of Business (Marketing) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Digital Media Research Centre Queensland University of Technology 2018 Keywords Social media, sport, netball, soccer, football, digital media, branding, sport communications, sport media “Gateway to the Sideline”: Brand communication on social media at large-scale sporting events i Abstract Social media platforms have become an essential component of a transmedia sport experience for fans. This has significant implications for sport organisations, which now need to strategically incorporate social media platforms into a communications plan alongside their traditional media counterparts. The emergence of social media as a popular form of communication in sport also provides opportunities for sport organisations, as they no longer rely on one-way methods of distribution through mainstream media platforms, and instead can connect with fans directly via social media. Initially, sport organisations took an ad hoc approach to social media strategy, yet as the use of social media in sport becomes increasingly normalised, and the affordances of social media platforms present opportunities to engage with new and existing sport fans, approaches to social media communications have become more strategic. Existing research has examined many aspects of the role social media plays in the transmedia sport experience, from the perspectives of fans and organisations. However, the approaches and strategies social media teams use within sport organisations remain largely unexamined from an inside perspective. Thus, the aim of this research is to document exactly how sport organisations use social media for communication, the motivations and considerations behind this use, and the tensions between sport fans and organisations that arise on social media surrounding the discussion of sport. -

England Netball Association

ALL ENGLAND NETBALL ASSOCIATION A History of Netball in England Through the Ages - To Present Day England Netball, Sports Park, 3 Oakwood Drive, Loughborough, Leicestershire. LE11 3QF www.ournetballhistory.org.uk EARLY BEGININGS 1891 • Game invented in USA by a YMCA Secretary, where it was then, and is now, called Basketball. First match recorded in America1900 (Boston) 1895 • Visit of Dr Justin Toles, an American, to Madam Österberg’s Physical Training College (then at Hampstead). Students were taught Basket Ball - indoors – there were no printed rules - no lines, circles or boundaries. The goals were two waste paper baskets hung on walls at each end of the hall. • Within Madame Bergman Österberg’s Report, dated 1895 the following was recorded : Basket Ball is an American game introduced into our College by Dr Toles ; its aim is to get the ball into the opponents’ basket or goal, the basket being placed at a height of about seven or eight feet. The play is entirely with the hands, and no player is allowed to hold the ball for more than 5 seconds. It is a good winter game and can be played by any number. We played a few games in the gymnasium under Dr Toles’ supervision. 1897 • Game played out of doors on grass. An American lady paid a visit to the College (who moved to Dartford), and taught the game as then played by women in America. • The students at Dartford introduced rings instead of baskets, the large ball and the division of the ground into three courts. • After completing the physical training course, graduates of the college were virtually guaranteed employment in girls’ schools throughout the country, with an ample yearly salary of £100! 1900 • The newly formed Ling Association (now the Physical Education Association) set up a sub-committee 1901 to revise and publish the first set of rules, 250 copies were published and many changes were adopted. -

Welsh Netball Annual Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 / 20 01 CONTENTS WELSH NETBALL BOARD 2019/20 Welsh Netball Board 01 President Merle Hamilton Chair Foreword 02 Vice-President Sheila Cooksley Annual Report 2019 / 20 Highlights 03 Vice-President Wendy Pressdee BEM CEO Summary 04 Chair Catherine Lewis Summer Tests 08 Vice-Chair Cath Hares Growth of the Business 09 Elected Director (Performance) Julia Longville Communications 10 Elected Director (Development) Melanie Hellerman Development 12 Elected Director (Compliance and Engagement) Carol Anthony Regional Reports 16 Appointed Director (Finance and Risk) Mike Bobbett Competitions 18 Appointed Director (Commercial) Kerry McDonald Performance 20 Appointed Director (Policy & Governance) Rhian Edwards Wales Age Group Teams and Performance Pathway 22 Appointed Director (HR) Zoe Grainger U17 Netball Europe 23 Appointed Director (Legal) Karen Meggit Celtic Dragons 24 Appointed Director (IT & Digital) Rob Rees Acknowledgements & Partners 26 Appointed Director (Communications & Marketing) Lowri Williams www.welshnetball.com 02 HIGHLIGHTS 03 OVER CHAIR FOREWORD CELTIC DRAGONS FAST5 SEMI-FINALISTS 2019 10,000 MEMBERS SILVER MEDALS WALES RETURNS TO This has been an exceptional season for Welsh Netball for lots of different AT NETBALL EUROPE CHAMPIONSHIP, reasons and as ever I thank the Welsh Netball Board, staff and the wider UNDER 21 AND UNDER 17 WORLD’S Welsh netball family for pulling together and driving forward. TOP 10 Annual Report 2019 / 20 Whilst we did not make the 2019 Netball World Cup, the Wales squad more than made up for it with some amazing performances in our 2019 Summer WALES’ SECOND EVER Tests in Cardiff. We welcomed netball nations from across the world and AFTER achieved fantastic wins against Malawi, Trinidad & Tobago and Grenada TEST NETBALL 45 7 TEST countries to ensure that our world rankings did not suffer. -

NETBALL EUROPE CONSTITUTION Approved at AGM, June 2020

NETBALL EUROPE CONSTITUTION Approved at AGM, June 2020 1 DEFINITIONS AND INTERPRETATION 1.1 In this Constitution: Accredited Delegate A person who is appointed by a Member National Association to represent it at a meeting of Netball Europe. Accredited Deputy A person who is appointed by resolution and is a voting Member of the body being represented. Associate Member Those National Governing Bodies of Netball Associations in Europe in Associate Membership of Netball Europe as defined under this Constitution. Byelaws The Byelaws of Netball Europe made by the Board as defined under this Constitution. Chair The person elected from time to time to be the Chair of Netball Europe as defined under this Constitution. Constitution The Constitution of Netball Europe. Council The meeting of the Members and Associate Members of Netball Europe. Director of Officiating (DO) The person elected from time to time to be the Director of Officiating of the Board of Netball Europe as defined under this Constitution. Emerging Member A country who has expressed interest in joining Netball Europe but does not yet meet NE requirements to become an Associate Member. Employee A person employed by a Member under a contract of service (employee on the payroll) or a contract for service (self-employed person). Finance Director The person elected from time to time to be the Finance Director of Netball Europe as defined under this Constitution. INF The International Netball Federation. Lapsed Member A Member who has not paid their subscription for more than one year. The Board The Board of Directors of Netball Europe elected from time to time as defined under this Constitution. -

Events Calendar 2012-2016

EVENTS CALENDAR 2012-2016 DATE EVENT HOST COUNTRY Last updated: 11 December 2012 2012 Jan 13-15 Hong Kong v Chinese Taipei v Thailand Hong Kong Mar 9-11 Netball Europe Championships - U17 Scotland Mar 9-11 Netball Europe Championships - U21 Northern Ireland Mar 8-10 Inter Gulf Tournament Al Ain, UAE Mar 16-18 IFNA Board Meeting Los Angeles Apr 10-14 England v Barbados England May 8-12 8 African Countries v 8 African Countries Tanzania May 21-25 Sportaccord Quebec, Canada May 25-27 Netball Europe Championships – Open England Jun 8-10 Netball Europe AGM & Council & Festival Gibraltar Jun 14 to 19 Sunshine Girls v South Africa Jamaica Jun 22-24 IFNA Board Meeting Glasgow Jun 26 to 30 Pacific Netball Series Fiji Jul 2-7 World University Netball Championship Cape Town Jul 6-7 Fiji v Singapore Fiji Jul 9-10 Fiji U21 v Singapore Fiji Jul 9-11 South Africa v Northern Ireland Cape Town Jul 11 to 21 AFNA (9) Countries Trinidad & Tobago Aug 15 to 18 Diamond Challenge, Malawi, Zambia, Botswana, SA Pretoria, South Africa Aug 25-31 8th Asian Championships Sri Lanka Sept 16 Australian Diamonds v Silver Ferns Australia Sept 18-26 England v Sunshine Girls England Sept 20 & 23 Silver Ferns v Australian Diamonds New Zealand Oct 11-16 Cook Islands v Scotland v Wales Cook Islands Oct 14- 1 Nov Aus. Diamonds v England v Silver Ferns v SA Australia/New Zealand Oct 20, 22, 24 Samoa v Scotland Samoa Nov 8-9 IFNA Board Meeting Auckland, New Zealand Nov 9-11 Fast5 Netball World Series Auckland, New Zealand Nov 24 & 25 Northern Ireland v Ireland Northern Ireland