Porcine Neural Progenitor Cells Derived from Tissue at Different

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Synergistic Genetic Interactions Between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models

BASIC RESEARCH www.jasn.org Synergistic Genetic Interactions between Pkhd1 and Pkd1 Result in an ARPKD-Like Phenotype in Murine Models Rory J. Olson,1 Katharina Hopp ,2 Harrison Wells,3 Jessica M. Smith,3 Jessica Furtado,1,4 Megan M. Constans,3 Diana L. Escobar,3 Aron M. Geurts,5 Vicente E. Torres,3 and Peter C. Harris 1,3 Due to the number of contributing authors, the affiliations are listed at the end of this article. ABSTRACT Background Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) are genetically distinct, with ADPKD usually caused by the genes PKD1 or PKD2 (encoding polycystin-1 and polycystin-2, respectively) and ARPKD caused by PKHD1 (encoding fibrocys- tin/polyductin [FPC]). Primary cilia have been considered central to PKD pathogenesis due to protein localization and common cystic phenotypes in syndromic ciliopathies, but their relevance is questioned in the simple PKDs. ARPKD’s mild phenotype in murine models versus in humans has hampered investi- gating its pathogenesis. Methods To study the interaction between Pkhd1 and Pkd1, including dosage effects on the phenotype, we generated digenic mouse and rat models and characterized and compared digenic, monogenic, and wild-type phenotypes. Results The genetic interaction was synergistic in both species, with digenic animals exhibiting pheno- types of rapidly progressive PKD and early lethality resembling classic ARPKD. Genetic interaction be- tween Pkhd1 and Pkd1 depended on dosage in the digenic murine models, with no significant enhancement of the monogenic phenotype until a threshold of reduced expression at the second locus was breached. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Anti-IDH3A Antibody (ARG42205)

Product datasheet [email protected] ARG42205 Package: 100 μl anti-IDH3A antibody Store at: -20°C Summary Product Description Rabbit Polyclonal antibody recognizes IDH3A Tested Reactivity Hu, Ms, Rat Tested Application ICC/IF, IHC-P, WB Host Rabbit Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Target Name IDH3A Antigen Species Human Immunogen Recombinant fusion protein corresponding to aa. 28-366 of Human IDH3A (NP_005521.1). Conjugation Un-conjugated Alternate Names Isocitrate dehydrogenase [NAD] subunit alpha, mitochondrial; EC 1.1.1.41; NAD; Isocitric dehydrogenase subunit alpha; + Application Instructions Application table Application Dilution ICC/IF 1:50 - 1:200 IHC-P 1:50 - 1:200 WB 1:500 - 1:2000 Application Note * The dilutions indicate recommended starting dilutions and the optimal dilutions or concentrations should be determined by the scientist. Positive Control Raji Calculated Mw 40 kDa Observed Size ~ 40 kDa Properties Form Liquid Purification Affinity purified. Buffer PBS (pH 7.3), 0.02% Sodium azide and 50% Glycerol. Preservative 0.02% Sodium azide Stabilizer 50% Glycerol Storage instruction For continuous use, store undiluted antibody at 2-8°C for up to a week. For long-term storage, aliquot and store at -20°C. Storage in frost free freezers is not recommended. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw www.arigobio.com 1/3 cycles. Suggest spin the vial prior to opening. The antibody solution should be gently mixed before use. Note For laboratory research only, not for drug, diagnostic or other use. Bioinformation Gene Symbol IDH3A Gene Full Name isocitrate dehydrogenase 3 (NAD+) alpha Background Isocitrate dehydrogenases catalyze the oxidative decarboxylation of isocitrate to 2-oxoglutarate. -

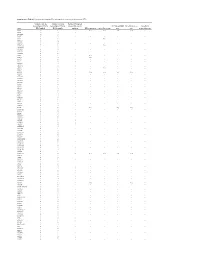

Supplementary Table S1. Prioritization of Candidate FPC Susceptibility Genes by Private Heterozygous Ptvs

Supplementary Table S1. Prioritization of candidate FPC susceptibility genes by private heterozygous PTVs Number of private Number of private Number FPC patient heterozygous PTVs in heterozygous PTVs in tumors with somatic FPC susceptibility Hereditary cancer Hereditary Gene FPC kindred BCCS samples mutation DNA repair gene Cancer driver gene gene gene pancreatitis gene ATM 19 1 - Yes Yes Yes Yes - SSPO 12 8 1 - - - - - DNAH14 10 3 - - - - - - CD36 9 3 - - - - - - TET2 9 1 - - Yes - - - MUC16 8 14 - - - - - - DNHD1 7 4 1 - - - - - DNMT3A 7 1 - - Yes - - - PKHD1L1 7 9 - - - - - - DNAH3 6 5 - - - - - - MYH7B 6 1 - - - - - - PKD1L2 6 6 - - - - - - POLN 6 2 - Yes - - - - POLQ 6 7 - Yes - - - - RP1L1 6 6 - - - - - - TTN 6 5 4 - - - - - WDR87 6 7 - - - - - - ABCA13 5 3 1 - - - - - ASXL1 5 1 - - Yes - - - BBS10 5 0 - - - - - - BRCA2 5 6 1 Yes Yes Yes Yes - CENPJ 5 1 - - - - - - CEP290 5 5 - - - - - - CYP3A5 5 2 - - - - - - DNAH12 5 6 - - - - - - DNAH6 5 1 1 - - - - - EPPK1 5 4 - - - - - - ESYT3 5 1 - - - - - - FRAS1 5 4 - - - - - - HGC6.3 5 0 - - - - - - IGFN1 5 5 - - - - - - KCP 5 4 - - - - - - LRRC43 5 0 - - - - - - MCTP2 5 1 - - - - - - MPO 5 1 - - - - - - MUC4 5 5 - - - - - - OBSCN 5 8 2 - - - - - PALB2 5 0 - Yes - Yes Yes - SLCO1B3 5 2 - - - - - - SYT15 5 3 - - - - - - XIRP2 5 3 1 - - - - - ZNF266 5 2 - - - - - - ZNF530 5 1 - - - - - - ACACB 4 1 1 - - - - - ALS2CL 4 2 - - - - - - AMER3 4 0 2 - - - - - ANKRD35 4 4 - - - - - - ATP10B 4 1 - - - - - - ATP8B3 4 6 - - - - - - C10orf95 4 0 - - - - - - C2orf88 4 0 - - - - - - C5orf42 4 2 - - - - -

Multi-Targeted Mechanisms Underlying the Endothelial Protective Effects of the Diabetic-Safe Sweetener Erythritol

Multi-Targeted Mechanisms Underlying the Endothelial Protective Effects of the Diabetic-Safe Sweetener Erythritol Danie¨lle M. P. H. J. Boesten1*., Alvin Berger2.¤, Peter de Cock3, Hua Dong4, Bruce D. Hammock4, Gertjan J. M. den Hartog1, Aalt Bast1 1 Department of Toxicology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2 Global Food Research, Cargill, Wayzata, Minnesota, United States of America, 3 Cargill RandD Center Europe, Vilvoorde, Belgium, 4 Department of Entomology and UCD Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California Davis, Davis, California, United States of America Abstract Diabetes is characterized by hyperglycemia and development of vascular pathology. Endothelial cell dysfunction is a starting point for pathogenesis of vascular complications in diabetes. We previously showed the polyol erythritol to be a hydroxyl radical scavenger preventing endothelial cell dysfunction onset in diabetic rats. To unravel mechanisms, other than scavenging of radicals, by which erythritol mediates this protective effect, we evaluated effects of erythritol in endothelial cells exposed to normal (7 mM) and high glucose (30 mM) or diabetic stressors (e.g. SIN-1) using targeted and transcriptomic approaches. This study demonstrates that erythritol (i.e. under non-diabetic conditions) has minimal effects on endothelial cells. However, under hyperglycemic conditions erythritol protected endothelial cells against cell death induced by diabetic stressors (i.e. high glucose and peroxynitrite). Also a number of harmful effects caused by high glucose, e.g. increased nitric oxide release, are reversed. Additionally, total transcriptome analysis indicated that biological processes which are differentially regulated due to high glucose are corrected by erythritol. We conclude that erythritol protects endothelial cells during high glucose conditions via effects on multiple targets. -

Involvement of CRH Receptors in the Neuroprotective Action of R-Apomorphine in the Striatal 6-OHDA Rat Model

Neuroscience & Medicine, 2013, 4, 299-318 299 Published Online December 2013 (http://www.scirp.org/journal/nm) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/nm.2013.44044 Involvement of CRH Receptors in the Neuroprotective Action of R-Apomorphine in the Striatal 6-OHDA Rat Model Mustafa Varçin1, Eduard Bentea1, Steven Roosens1, Yvette Michotte1, Sophie Sarre1,2* 1Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry and Drug Analysis, Center for Neurosciences, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Brussels, Belgium; 2Belgian Pharmacists Association, Medicines Control Laboratory, Brussels, Belgium. Email: *[email protected] Received October 21st, 2013; revised November 20th, 2013; accepted December 10th, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Mustafa Varçin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ABSTRACT The dopamine D1-D2 receptor agonist, R-apomorphine, has been shown to be neuroprotective in different models of Parkinson’s disease. Different mechanisms of action for this effect have been proposed, but not verified in the striatal 6-hydroxydopamine rat model. In this study, the expression of a set of genes involved in 1) signaling, 2) growth and differentiation, 3) neuronal regeneration and survival, 4) apoptosis and 5) inflammation in the striatum was measured after a subchronic R-apomorphine treatment (10 mg/kg/day, subcutaneously, during 11 days) in the striatal 6-hydroxy- dopamine rat model. The expression of 84 genes was analysed by using the rat neurotrophins and receptors RT2 Pro- filer™ PCR array. The neuroprotective effects of R-apomorphine in the striatal 6-hydroxydopamine model were con- firmed by neurochemical and behavioural analysis. -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

MBT1 to Promote Repression of Notch Signaling Via Histone Demethylase

1 RBPJ/CBF1 interacts with L3MBTL3/MBT1 to promote repression 2 of Notch signaling via histone demethylase KDM1A/LSD1 3 Tao Xu1,†, Sung-Soo Park1,†, Benedetto Daniele Giaimo2,†, Daniel Hall3, Francesca Ferrante2, 4 Diana M. Ho4, Kazuya Hori4, Lucas Anhezini5,6, Iris Ertl7,8, Marek Bartkuhn9, Honglai Zhang1, 5 Eléna Milon1, Kimberly Ha1, Kevin P. Conlon1, Rork Kuick10, Brandon Govindarajoo11, Yang 6 Zhang11, Yuqing Sun1, Yali Dou1, Venkatesha Basrur1, Kojo S. J. Elenitoba-Johnson1, Alexey I. 7 Nesvizhskii1,11, Julian Ceron7, Cheng-Yu Lee5, Tilman Borggrefe2, Rhett A. Kovall3 & Jean- 8 François Rual1,* 9 1Department of Pathology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; 10 2Institute of Biochemistry, University of Giessen, Friedrichstrasse 24, 35392, Giessen, Germany; 11 3Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry and Microbiology, University of Cincinnati 12 College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA; 13 4Department of Cell Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA; 14 5Life Sciences Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; 15 6Current address: Instituto de Ciências Biológicas e Naturais, Universidade Federal do 16 Triângulo Mineiro, Uberaba, MG 38025-180, Brasil; 17 7Cancer and Human Molecular Genetics, Bellvitge Biomedical Research Institute, L’Hospitalet 18 de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain; 19 8Current address: Department of Urology, Medical University of Vienna, Währiger Gürtel 18-20, 20 Vienna, Austria; 21 9Institute for Genetics, University of Giessen, Heinrich-Buff-Ring 58, 35390, Giessen, Germany; 22 10Center for Cancer Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 23 48109, USA; 24 11Department of Computational Medicine & Bioinformatics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 25 MI 48108, USA; 26 †These authors contributed equally to this work; 27 *Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.F.R. -

Dominant Negative Selection of Heterologous Genes

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 89, pp. 9410-9414, October 1992 Genetics Dominant negative selection of heterologous genes: Isolation of Candida albicans genes that interfere with Saccharomyces cerevisiae mating factor-induced cell cycle arrest MALCOLM WHITEWAY*, DANIEL DIGNARD, AND DAVID Y. THOMAS Eukaryotic Genetics Group, National Research Council of Canada, Biotechnology Research Institute, Montr6al, Qu6bec, Canada, H4P 2R2 Communicated by Ira Herskowitz, June 30, 1992 (receivedfor review December 2, 1991) ABSTRACT We have used a genomic library of Candida analysis of the pheromone response pathway. Recessive albicans to transform Saccharomyces cerevisiae and screened mutations leading to pheromone resistance (7, 8) have iden- for genes that act similarly to dominant negative mutations by tified genes encoding the a-pheromone receptor (9, 10), the interfering with pheromone-mediated cell cycle arrest. Six pheromone response G-protein fB subunit (11), two protein different plasmids were identified from 2000 transformants; kinases (12, 13), a transcription factor (14), and a product four have been sequenced. One gene (CZFI) encodes a protein apparently involved in regulating cyclin activity (8). Domi- with structural motifs characteristic of a transcription factor. nant mutations leading to pheromone resistance led to the A second gene (CCNI) encodes a cyclin homologue, a third isolation of a G1 cyclin (15). In addition, overexpression ofS. (CRLI) encodes a protein with sequence similarity to GTP- cerevisiae genes that reduce pheromone sensitivity has al- binding proteins of the RHO family, and a fourth (CEKI) lowed the identification of a G-protein a subunit (16) as well encodes a putative kinase of the ERK family. Since CEKI as the KSS1 protein kinase (17). -

Supplementary Table S4. FGA Co-Expressed Gene List in LUAD

Supplementary Table S4. FGA co-expressed gene list in LUAD tumors Symbol R Locus Description FGG 0.919 4q28 fibrinogen gamma chain FGL1 0.635 8p22 fibrinogen-like 1 SLC7A2 0.536 8p22 solute carrier family 7 (cationic amino acid transporter, y+ system), member 2 DUSP4 0.521 8p12-p11 dual specificity phosphatase 4 HAL 0.51 12q22-q24.1histidine ammonia-lyase PDE4D 0.499 5q12 phosphodiesterase 4D, cAMP-specific FURIN 0.497 15q26.1 furin (paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme) CPS1 0.49 2q35 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase 1, mitochondrial TESC 0.478 12q24.22 tescalcin INHA 0.465 2q35 inhibin, alpha S100P 0.461 4p16 S100 calcium binding protein P VPS37A 0.447 8p22 vacuolar protein sorting 37 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) SLC16A14 0.447 2q36.3 solute carrier family 16, member 14 PPARGC1A 0.443 4p15.1 peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha SIK1 0.435 21q22.3 salt-inducible kinase 1 IRS2 0.434 13q34 insulin receptor substrate 2 RND1 0.433 12q12 Rho family GTPase 1 HGD 0.433 3q13.33 homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase PTP4A1 0.432 6q12 protein tyrosine phosphatase type IVA, member 1 C8orf4 0.428 8p11.2 chromosome 8 open reading frame 4 DDC 0.427 7p12.2 dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) TACC2 0.427 10q26 transforming, acidic coiled-coil containing protein 2 MUC13 0.422 3q21.2 mucin 13, cell surface associated C5 0.412 9q33-q34 complement component 5 NR4A2 0.412 2q22-q23 nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 2 EYS 0.411 6q12 eyes shut homolog (Drosophila) GPX2 0.406 14q24.1 glutathione peroxidase -

Recount Brain Example with Data from SRP027383

recount_brain example with data from SRP027383 true Abstract This is an example on how to use recount_brain applied to the SRP027383 study. We show how to download data from recount2, add the sample metadata from recount_brain, explore the sample metadata and the gene expression data, and perform a gene expression analysis. Introduction This document is an example of how you can use recount_brain. We will use the data from the SRA study SRP027383 which is described in “RNA-seq of 272 gliomas revealed a novel, recurrent PTPRZ1-MET fusion transcript in secondary glioblastomas” (Bao, Chen, Yang, Zhang, et al., 2014). As you can see in Figure @ref(fig:runselector) a lot of the metadata for these samples is missing from the SRA Run Selector which makes it a great case for using recount_brain. We will show how to add the recount_brain metadata and perform a gene differential expression analysis using this information. Sample metadata Just like any study in recount2 (Collado-Torres, Nellore, Kammers, Ellis, et al., 2017), we first need to download the gene count data using recount::download_study(). Since we will be using many functions from the recount package, lets load it first1. ## Load the package library('recount') Download gene data Having loaded the package, we next download the gene-level data. if(!file.exists(file.path('SRP027383', 'rse_gene.Rdata'))) { download_study('SRP027383') } load(file.path('SRP027383', 'rse_gene.Rdata'), verbose = TRUE) ## Loading objects: ## rse_gene 1If you are a first time recount user, we recommend first reading the package vignette at bioconductor.org/packages/recount. 1 Figure 1: SRA Run Selector information for study SRP027383. -

Centrosome Impairment Causes DNA Replication Stress Through MLK3

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Centrosome impairment causes DNA replication stress through MLK3/MK2 signaling and R-loop formation Zainab Tayeh 1, Kim Stegmann 1, Antonia Kleeberg 1, Mascha Friedrich 1, Josephine Ann Mun Yee Choo 1, Bernd Wollnik 2, and Matthias Dobbelstein 1* 1) Institute of Molecular Oncology, Göttingen Center of Molecular Biosciences (GZMB), University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany 2) Institute of Human Genetics, University Medical Center Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany *Lead Contact. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M. D. (e-mail: [email protected]; ORCID 0000-0001-5052-3967) Running title: Centrosome integrity supports DNA replication Key words: Centrosome, CEP152, CCP110, SASS6, CEP152, Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), DNA replication, DNA fiber assays, R-loops, MLK3, MK2 alias MAPKAPK2, Seckel syndrome, microcephaly. Highlights: • Centrosome defects cause replication stress independent of mitosis. • MLK3, p38 and MK2 (alias MAPKAPK2) are signalling between centrosome defects and DNA replication stress through R-loop formation. • Patient-derived cells with defective centrosomes display replication stress, whereas inhibition of MK2 restores their DNA replication fork progression and proliferation. 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.09.898684; this version posted January 10, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity.