Bassil-Morozow-“Loki Then and Now: the Trickster Against Civilization”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Norse Myth Guide

Norse Myth If it has a * next to it don’t worry about it for the quiz. Everything else is fair game within reason as I know this is a lot. Just make sure you know the basics. Heimdall -Characteristics -Can hear grass grow -Needs only as much sleep as a bird -Guards Bifrost -Will kill and be killed by Loki at Ragnarok -He is one of the Aesir -Has foresight like the Vanir -Other Names -Vindhler -Means "wind shelter" -The White God As -Hallinskidi -Means "bent stick" but actually refers to rams -Gullintani -Received this nickname from his golden teeth -Relationships -Grandfather to Kon the Young -Born of the nine mothers -Items -Gjallarhorn -Will blow this to announce Ragnarok -Sword Hofund -Horse Golltop -Places -Lives on "heavenly mountain" Himinbjorg -Stories -Father of mankind -He went around the world as Rig -He slept with many women -Three of these women, Edda, Amma, and Modir, became pregnant -They gave birth to the three races of mankind -Jarl, Karl, and Thrall -Recovering Brisingamen -Loki steals Brisingamen from Freya -He turns himself into a seal and hides -Freya enlists Heimdall to recover the necklace -They find out its Loki, so Heimdall goes to fight him -Heimdall also turns into a seal, and they fight at Singasteinn -Heimdall wins, and returns the necklace to Freya -Meaning of sword -A severed head was thrown at Heimdall -After this incident, a sword is referred to as "Heimdall's head" -Possession of knowledge -Left his ear in the Well of Mimir to gain knowledge Aegir* -Characteristics -God of the ocean/sea -Is sometimes said -

Old Norse Mythology — Comparative Perspectives Old Norse Mythology— Comparative Perspectives

Publications of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature No. 3 OLd NOrse MythOLOgy — COMParative PersPeCtives OLd NOrse MythOLOgy— COMParative PersPeCtives edited by Pernille hermann, stephen a. Mitchell, and Jens Peter schjødt with amber J. rose Published by THE MILMAN PARRY COLLECTION OF ORAL LITERATURE Harvard University Distributed by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England 2017 Old Norse Mythology—Comparative Perspectives Published by The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, England Copyright © 2017 The Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature All rights reserved The Ilex Foundation (ilexfoundation.org) and the Center for Hellenic Studies (chs.harvard.edu) provided generous fnancial and production support for the publication of this book. Editorial Team of the Milman Parry Collection Managing Editors: Stephen Mitchell and Gregory Nagy Executive Editors: Casey Dué and David Elmer Production Team of the Center for Hellenic Studies Production Manager for Publications: Jill Curry Robbins Web Producer: Noel Spencer Cover Design: Joni Godlove Production: Kristin Murphy Romano Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Hermann, Pernille, editor. Title: Old Norse mythology--comparative perspectives / edited by Pernille Hermann, Stephen A. Mitchell, Jens Peter Schjødt, with Amber J. Rose. Description: Cambridge, MA : Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, 2017. | Series: Publications of the Milman Parry collection of oral literature ; no. 3 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017030125 | ISBN 9780674975699 (alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Mythology, Norse. | Scandinavia--Religion--History. Classifcation: LCC BL860 .O55 2017 | DDC 293/.13--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017030125 Table of Contents Series Foreword ................................................... -

The Avengers (Action) (2012)

1 The Avengers (Action) (2012) Major Characters Captain America/Steve Rogers...............................................................................................Chris Evans Steve Rogers, a shield-wielding soldier from World War II who gained his powers from a military experiment. He has been frozen in Arctic ice since the 1940s, after he stopped a Nazi off-shoot organization named HYDRA from destroying the Allies with a mystical artifact called the Cosmic Cube. Iron Man/Tony Stark.....................................................................................................Robert Downey Jr. Tony Stark, an extravagant billionaire genius who now uses his arms dealing for justice. He created a techno suit while kidnapped by terrorist, which he has further developed and evolved. Thor....................................................................................................................................Chris Hemsworth He is the Nordic god of thunder. His home, Asgard, is found in a parallel universe where only those deemed worthy may pass. He uses his magical hammer, Mjolnir, as his main weapon. The Hulk/Dr. Bruce Banner..................................................................................................Mark Ruffalo A renowned scientist, Dr. Banner became The Hulk when he became exposed to gamma radiation. This causes him to turn into an emerald strongman when he loses his temper. Hawkeye/Clint Barton.........................................................................................................Jeremy -

1 the Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor E

1 The Legendary Saga of the Volsungs Cecelia Lefurgy Viking Art and Literature October 4, 2007 Professor Tinkler and Professor Erussard Stories that are passed down through oral and written traditions are created by societies to give meaning to, and reinforce the beliefs, rules and habits of a particular culture. For Germanic culture, The Saga of the Volsungs reflected the societal traditions of the people, as well as their attention to mythology. In the Saga, Sigurd of the Volsung 2 bloodline becomes a respected and heroic figure through the trials and adventures of his life. While many of his encounters are fantastic, they are also deeply rooted in the values and belief structures of the Germanic people. Tacitus, a Roman, gives his account of the actions and traditions of early Germanic peoples in Germania. His narration remarks upon the importance of the blood line, the roles of women and also the ways in which Germans viewed death. In Snorri Sturluson’s The Prose Edda, a compilation of Norse mythology, Snorri Sturluson touches on these subjects and includes the perception of fate, as well as the role of shape changing. Each of these themes presented in Germania and The Prose Edda aid in the formation of the legendary saga, The Saga of the Volsungs. Lineage is a meaningful part of the Germanic culture. It provides a sense of identity, as it is believed that qualities and characteristics are passed down through generations. In the Volsung bloodline, each member is capable of, and expected to achieve greatness. As Sigmund, Sigurd’s father, lay wounded on the battlefield, his wife asked if she should attend to his injuries so that he may avenge her father. -

Winds of Salem Pdf Free Download

WINDS OF SALEM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Melissa de La Cruz | 324 pages | 01 May 2015 | Little, Brown & Company | 9781401330224 | English | United States Winds of Salem PDF Book So we finally reach then end of this journey. The vague ending with Freya, Killian, and Loki in the bar. I really enjoyed this series and Ms. Back to the point about characters losing their powers, Freya in the past still has hers which doesn't make sense and is incongruous with how the passage of time works in the novel. I'm sad. Joanna and Norman have never had a stronger marriage. So, overall, it's safe to say I a I received this book via NetGalley. I wish Cruz had not included a spirit harassing Joanna that leads them to Salem. And I loved the Norse mythology. In the present, Ingrid has doubts over her relationship with Matt when she sees how close he is with his daughter's mother, Mariza. However, she is also the author of the children's fairytale series, Descendants, which seems to be doing pretty well. It turns out that Bran is Loki and Killian is Balder, therefore, the end of the plot of the first book is the Beauchamp family prevening Loki from enacting Ragnorak as punishment for Freya choosing Balder. As you were reading this, did you feel her conflict? This in and of itself is highly unoriginal. May Meanwhile, twenty-first-century North Hampton has its own snares. Other Editions Okay, now that I introduced you to our so called wonderful cast of characters again. -

Frigg, Astghik and the Goddess of the Crete Island

FRIGG, ASTGHIK AND THE GODDESS OF THE CRETE ISLAND Dedicated to the goddesses-mothers of Armenia and Sweden PhD in Art History Vahanyan V. G., Prof. Vahanyan G. A. Contents Intrоduction Relations between Frigg and the Goddess of the Crete Island Motifs in Norse Mythology Motifs in Armenian Mythology Artifacts Circle of the World Afterword References Introduction According to conventional opinion, the well-known memorial stone (Fig. 1a) from the Swedish island Gotland (400-600 AC) depicts goddess Frigg holding snakes. The unique statuettes of a goddess holding snakes are discovered on Crete (Fig. 1b), which date to c. 1600 BC1. The depiction of Frigg embodies a godmother with her legs wide open to give birth. In Norse mythology Frigg, Frige (Old Norse Frigg), Frea or Frija (Frija – “beloved”) is the wife of Odin. She is the mother of the three gods Baldr, Hodr and Hermodr. a b Fig. 1. (a) Memorial stone from the Swedish island Gotland (400-600 AC) depicting Frigg holding snakes. (b) Goddess holding snakes, Crete (c. 1600 BCE) The Swedish stone from Gotland island depicts the godmother, who is sitting atop the mountain before childbirth (Fig. 1а). Her hands are raised and she is holding two big snakes-dragons. The composition symbolizes the home/mountain of dragons (volcanic mountain). The composite motif of the depiction on the memorial stone, according to the 1 The findings belong to Crete-Minoan civilization and are found in the upper layers of the New Palace in Knossos. Two items are discovered (Archaeological Museum, Heraklion) authors, stems to the archetypes in the Old Armenian song “The birth of Vahagn” 2. -

Simonson's Thor Bronze Age Thor New Gods • Eternals

201 1 December .53 No 5 SIMONSON’S THOR $ 8 . 9 BRONZE AGE THOR NEW GODS • ETERNALS “PRO2PRO” interview with DeFALCO & FRENZ HERCULES • MOONDRAGON exclusive MOORCOCK interview! 1 1 1 82658 27762 8 Volume 1, Number 53 December 2011 Celebrating The Retro Comics Experience! the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks . COVER ARTIST c n I , s Walter Simonson r e t c a r a COVER COLORIST h C l Glenn Whitmore e v r a BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 M COVER DESIGNERS 1 1 0 2 Michael Kronenberg and John Morrow FLASHBACK: The Old Order Changeth! Thor in the Early Bronze Age . .3 © . Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, and Gerry Conway remember their time in Asgard s n o i PROOFREADER t c u OFF MY CHEST: Three Ways to End the New Gods Saga . .11 A Rob Smentek s c The Eternals, Captain Victory, and Hunger Dogs—how Jack Kirby’s gods continued with i m SPECIAL THANKS o C and without the King e g Jack Abramowitz Brian K. Morris a t i r FLASHBACK: Moondragon: Goddess in Her Own Mind . .19 e Matt Adler Luigi Novi H f Getting inside the head of this Avenger/Defender o Roger Ash Alan J. Porter y s e t Bob Budiansky Jason Shayer r FLASHBACK: The Tapestry of Walter Simonson’s Thor . .25 u o C Sal Buscema Walter Simonson Nearly 30 years later, we’re still talking about Simonson’s Thor —and the visionary and . -

Sample Pages to Thor

1 only A Stranger Arrives The air was dry and cold near the small town of Puente Antiguo, New Mexico. Darcy Lewis sat in the driver’s seatReview of an old van full of expensive scientic equipment. She was a college student working with scientist Jane Foster. Another scientist, ForDr. Erik Selvig, sat in the passenger seat. In the back of the van, Jane- opened the roof and climbed onto it. Selvig followed her, and they looked up into the darkness. “So what exactly are we looking for?” Selvig asked. He was a friend of Jane’s father and knew her well. “Why did you ask me to join you here in New Mexico?” “I told youSample. Something strange is happening in the night sky and I need your help,” Jane replied. “It’s a little dierent each time. Once it was a pool of stars in a corner of the sky. But last week it was a rainbow—” A noise from her computer stopped her. “Wait for it!” she said excitedly. Nothing happened. The sky above them stayed calm and black. Darcy put her head out of the window and looked up at Jane. “Can I turn on the radio?” she asked. She sounded bored. “No!” Jane replied angrily. She and Selvig climbed back inside the van. “I don’t understand,” she said. She opened a small book and looked at her notes. She always carried this notebook—inside it was her life’s work. M01_THOR_SB3_GLB_05991.indd 1 3/6/18 1:53 PM 2 “These changes have happened many times, always at night, Erik!” She checked her computer. -

The Prose Edda

THE PROSE EDDA SNORRI STURLUSON (1179–1241) was born in western Iceland, the son of an upstart Icelandic chieftain. In the early thirteenth century, Snorri rose to become Iceland’s richest and, for a time, its most powerful leader. Twice he was elected law-speaker at the Althing, Iceland’s national assembly, and twice he went abroad to visit Norwegian royalty. An ambitious and sometimes ruthless leader, Snorri was also a man of learning, with deep interests in the myth, poetry and history of the Viking Age. He has long been assumed to be the author of some of medieval Iceland’s greatest works, including the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, the latter a saga history of the kings of Norway. JESSE BYOCK is Professor of Old Norse and Medieval Scandinavian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Professor at UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. A specialist in North Atlantic and Viking Studies, he directs the Mosfell Archaeological Project in Iceland. Prof. Byock received his Ph.D. from Harvard University after studying in Iceland, Sweden and France. His books and translations include Viking Age Iceland, Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, Feud in the Icelandic Saga, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki and The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. SNORRI STURLUSON The Prose Edda Norse Mythology Translated with an Introduction and Notes by JESSE L. BYOCK PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN CLASSICS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., -

Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? 2019

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Tomáš Lukáč Deadpool – Anti-Hero, Trickster? Both, Neither? Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. 2019 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Tomáš Lukáč 2 I would like to thank everyone who helped to bring this thesis to life, mainly to my supervisor, Jeffrey Alan Vanderziel, B.A. for his patience, as well as to my parents, whose patience exceeded all reasonable expectations. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ...…………………………………………………………………………...6 Tricksters across Cultures and How to Find Them ........................................................... 8 Loki and His Role in Norse Mythology .......................................................................... 21 Character of Deadpool .................................................................................................... 34 Comic Book History ................................................................................................... 34 History of the Character .............................................................................................. 35 Comic Book Deadpool ................................................................................................ 36 Films ............................................................................................................................ 43 Deadpool (2016) -

A Saga of Odin, Frigg and Loki Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DARK GROWS THE SUN : A SAGA OF ODIN, FRIGG AND LOKI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matt Bishop | 322 pages | 03 May 2020 | Fensalir Publishing, LLC | 9780998678924 | English | none Dark Grows the Sun : A saga of Odin, Frigg and Loki PDF Book He is said to bring inspiration to poets and writers. A number of small images in silver or bronze, dating from the Viking age, have also been found in various parts of Scandinavia. They then mixed, preserved and fermented Kvasirs' blood with honey into a powerful magical mead that inspired poets, shamans and magicians. Royal Academy of Arts, London. Lerwick: Shetland Heritage Publications. She and Bor had three sons who became the Aesir Gods. Thor goes out, finds Hymir's best ox, and rips its head off. Born of nine maidens, all of whom were sisters, He is the handsome gold-toothed guardian of Bifrost, the rainbow bridge leading to Asgard, the home of the Gods, and thus the connection between body and soul. He came round to see her and entered her home without a weapon to show that he came in peace. They find themselves facing a massive castle in an open area. The reemerged fields grow without needing to be sown. Baldur was the most beautiful of the gods, and he was also gentle, fair, and wise. Sjofn is the goddess who inclines the heart to love. Freyja objects. Eventually the Gods became weary of war and began to talk of peace and hostages. There the surviving gods will meet, and the land will be fertile and green, and two humans will repopulate the world. -

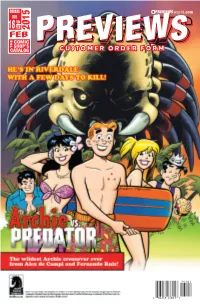

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells”