Art and Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Groningen Frontierstad Bij Het Scheiden Van De Markt

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Frontierstad bij het scheiden van de markt. Deventer Holthuis, Paul IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 1993 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Holthuis, P. (1993). Frontierstad bij het scheiden van de markt. Deventer: militair, demografisch, economisch; 1578-1648. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 12-11-2019 en, 1602, Samenvatting en besluit Berends, wartier', 85. :keningvan 'D, timmer- ., 8 maart Aan de hand van allerlei, soms beperkte gegevens is aangetoond dat Deventer 16r3. gedurende de gewelddadige periode 1578-Í648 afzakte van een aanzienliik han- mei 16zo. -

Layout Version Gerlach

The Brock Review Volume 10 (2008) © Brock University Greenscape as Screenscape: The Cinematic Urban Garden 1 Nina Gerlach Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Abstract : The relationship between city and garden appears in many feature films in order to visualize narrative dualisms. In particular, the character of the boundary - as a fundamental medial characteristic of gardens - determines the meaning of the represented space. According to the Western representation of ideal places and the historically-developed antagonism of city and garden, the boundary defines the latter as the diametrically opposed utopian antithesis to urban life. This antagonism is used, for example, in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970) in the political context of World War II, or as in Being There (1979), embedded in a philosophical discourse centered on Voltaire and Sartre. The dystopian city of Los Angeles in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) lacks space not only for gardens, but for any natural environment in general. The only garden that remains, exists as a kind of Paradise Lost , a placeless topos with a unicorn, banished into and limited by the world of imagination of the protagonist. As this example indicates, the cinematic garden and particularly the more specialized topic of the relationship between the garden and the city within cinema is still an under-examined realm of the research of garden history.2 In cinematic genres where the city is usually presented as the essential character -- such as in Neorealism, Film Noir, and dystopian science fiction -- garden space is hardly discovered. 3 These types of films frequently transport an extremely negative connotation of the city. -

Apeldoorn / Deventer / Zutphen Profiel Cultuurregio Stedendriehoek

Apeldoorn / Deventer / Zutphen Profiel Cultuurregio Stedendriehoek 30 oktober 2018 Gezamenlijk cultuurprofiel van Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zutphen Aanleiding voor het opstellen van een Cultuurprofiel Doelstellingen • Het ministerie van OCW heeft regio’s gevraagd een profiel op te stellen • Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zutphen hebben samen de kans gegrepen om waarin steden hun gezamenlijke visie op kunst en cultuur in de regio het veld te verbinden in de ontwikkeling van een regionaal cultuurprofiel beschrijven, de uitdagingen die zij gezamenlijk zien en willen oppakken en daarmee een agenda voor gezamenlijk cultuurbeleid te creëren en de wijze waarop het landelijke en lokale cultuurbeleid en regionale • Gezien de diversiteit in karakter, bereik en samenwerking in de disciplines samenwerking kunnen bijdragen aan oplossingen hiervoor is gekozen voor een gelaagde, gedifferentieerde aanpak. Dit profiel geeft • Met behulp van deze profielen kunnen het rijk en lagere overheden beter dan ook niet een compleet beeld, maar wel kwaliteiten en keuzes rekening houden met de samenstelling en de behoefte van de bevolking, • Dankzij dit profiel en de beleidsmaatregelen van de overheden die volgen met de identiteit en verhalen uit de regio en met het lokale klimaat voor kunnen bestaande samenwerkingsverbanden een impuls krijgen en de makers en kunstenaars in de verschillende disciplines nieuwe initiatieven, ook bovenregionaal, tot bloei worden gebracht Proces Resultaat • Binnen het Landsdeel Oost hebben gemeenten met provincies bepaald Dit Regionaal Cultuurprofiel bestaat uit vijf programmalijnen die samen de hoe de regionale cultuurprofielen in beeld konden worden gebracht agenda vormen voor samenwerking in onze regio en met andere regio’s: • DSP heeft een verkenning verricht voor Apeldoorn, Deventer en Zwolle A. -

1 Cloisters As a Place of Spiritual Awakening

Cloisters as a Place of Spiritual Awakening | by Manolis Iliakis Workshop DAS | Dance Architecture Spatiality in Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert © Manolis Iliakis The crossroads of daily and spiritual life in medieval monasteries of the West The English word for enclosed garden (cloister) is derived from the Latin parent word claustrum, meaning a bolt which secured the door. The more recent latch is the contemporary version of this bolt. This seems to be symbolic of the monks' isolation from the outside world, facilitating contact with the inner consciousness. The word is also associated with the footpaths outside the monastery courtyard, which were often used by monks for a kind of walking meditation. The English words cloistered and claustral describe the monastic way of life. The metonymic name “Kloster” in German means monastery. The German word for enclosed garden is Kreuzgang (meaning crossroads). Around the perimeter of an outdoor garden, a roofed portico (porch-like gallery) was constructed, its columns terminating in arcades. In larger monasteries, a second-level perimetric portico was built. Often, there was a well, fountain or water basin. This element was not always placed at the centre, as for example at the monastery of Ganagobie Abbey1. The resulting asymmetry, emphasized by the placement of plants and trees, brought another architectural aspect to the typically square floor plan. This typology is a characteristic of most Western medieval monasteries, as well as cathedrals. These spaces were adjacent to the main church or a chapel and are the heart of the monastery. A gateway facilitated direct access from one space to another, the sense that one has in the closed space of the church being conveyed to the cloister and vice-versa. -

Dashboard Statenvoorstel

Dashboard Statenvoorstel Datum GS-kenmerk Inlichtingen bij 21 november 2017 2017/0410970 M ten Heggeler, telefoon 038-499 78 64 e-mail: [email protected] Titel/Onderwerp PS kenmerk Topwerklocaties in West-Overijssel en PS/2017/798 procesfinanciering vervolgaanpak Omschrijving van besluit of onderwerp: GS hebben in opdracht van PS 5 topwerklocaties geselecteerd in West-Overijssel. GS stellen voor aan PS om deze locaties vast te stellen en op te nemen in de Omgevingsvisie bij de eerstvolgende actualisatie. Tevens worden PS gevraagd in te stemmen met de vervolgaanpak topwerklocaties West-Overijssel en de financiering ervan. Participatieladder Vorm van participatie (Rol van participant) Bestuursstijl (Rol van het bestuur) Initiatiefnemer, Beleidseigenaar, Bevoegd gezag Faciliterende stijl Samenwerkingspartner Samenwerkende stijl Medebeslisser Delegerende stijl Adviseur inspraak Participatieve stijl Adviseur eindspraak Consultatieve stijl Toeschouwer, Ontvanger informatie, Informant Open autoritaire stijl Geen rol Gesloten autoritaire stijl Wat wilt u van PS: Fase van het onderwerp/besluit: : Ter kennis geven Informerend Overleg Verkennend Brainstorm Mede-ontwerp/coproductie Samenwerking Besluitvormend Besluitvorming Inspraak Reflectie Uitvoerend Overig, namelijk: Evaluatie Reflectie Overig, namelijk: Toekomstige activiteiten Relevante achtergrondinformatie Als PS instemmen met de financiering van de Advies expertgroep topwerklocaties West-Overijssel, vervolguitvoering kan daarmee worden gestart. Omgevingsvisie paragraaf topwerklocaties -

De NS Wandeling Ijsselvallei

Wandelnet IJsselvallei dag 1 & 2 Startpunt voor wandelend Nederland NS-wandeling Zutphen – Deventer Inleiding Markering van de route Wandelnet heeft in samenwerking met NS een serie U volgt de geel-rode markering van het Hanzestedenpad. De wandelingen van station naar station samengesteld. Deze markering vindt u op een hek, lantaarnpaal of op paaltjes NS-wandelingen volgen een gedeelte van een Lange-Afstand- van wandelnetwerk Salland. Er is vooral daar gemarkeerd Wandelpad (LAW). De tweedaagse route IJsselvallei volgt waar twijfel over de juiste route zou kunnen ontstaan. een deel van het Hanzestedenpad (Streekpad 11, Doesburg– Waar routebeschrijving en markering verschillen, blijft u de Kampen 122 km). De eerste dag loopt u in 18 km van station markering volgen. Tussentijdse veranderingen in het terrein Zutphen naar Deventer. De tweede dag, van Deventer naar worden zo ondervangen. De markering van het pad wordt station Olst, is 14 km. Uiteraard is het ook mogelijk om alleen onderhouden door vrijwilligers van Wandelnet. dag 1 of alleen dag 2 te lopen. Bij (extreem) hoogwater in de IJssel zijn enkele delen van Wandelnet de route niet begaanbaar; alternatieven zijn op de kaart In ons land zijn circa 40 Lange-Afstand-Wandelpaden® weergegeven (met onderbroken lijn). (LAW's), in lengte variërend van 80 tot 725 km, beschreven Veel wandelplezier! en gemarkeerd. Alle activiteiten op het gebied van LAW's in Nederland worden gecoördineerd door Wandelnet. Naast het Heen- en terugreis ontwikkelen en beheren van LAW's behartigt Wandelnet de Station Zutphen (begin route dag 1) is per trein bereikbaar belangen van alle recreatieve wandelaars op lokaal, regionaal vanaf Deventer/Zwolle, Arnhem/Nijmegen/Roosendaal, en en landelijk niveau. -

The Pre-Raphaelite Garden Enclosed Dr. Dinah

Naturally Artificial: The Pre-Raphaelite Garden Enclosed Dr. Dinah Roe 2 Garden historian Brent Elliott tells us that the mid-Victorian revival of the enclosed garden “was not primarily a scholarly movement” but an artistic one, and cites depictions of such gardens in the pictures of “many of the Pre-Raphaelite circle” as evidence.1 WH Mallock’s satirical 1872 “recipe” for making “a modern Pre-Raphaelite poem” also recognizes the prominence of the walled garden motif in Pre-Raphaelite work. Among his key ingredients are “damozels” placed “in a row before a stone wall, with an apple-tree between each, and some larger flowers at their feet.”2 He is probably thinking of the frontispiece of William Morris’s The Earthly Paradise, a volume whose title evokes an enclosed garden; as landscape architects Rob Aben and Saskia De Wit point out, the word “Paradise is derived from the Persian word Pairidaeza, literally meaning “surrounded by walls.”3 I want to demonstrate that it is this sense of what garden theorist Elizabeth Ross calls “surroundedness” that attracts Pre-Raphaelites to the enclosed garden. Ross writes that “being surrounded” provides “a basic sensory and kinesthetic” experience signifying “comfort, security, passivity, rest, privacy, intimacy, sensory focus, and concentrated attention.”4 Walled gardens, in other words, provide the material and metaphorical conditions for experiencing and making art. Focussing on Christina Rossetti’s poems, “On Keats” (1849) and “Shut Out” (1856); Charles Collins’s painting Convent Thoughts (1851) and William Morris’s poem, “The Defence of Guenevere” (1858), I want to examine the ways in which Pre-Raphaelitism begins to conceive of the walled garden as an analogue of both contemporary art and artistic consciousness.5 I will argue that the Pre-Raphaelite revival of the enclosed garden modernizes what was once a medieval space by remaking the traditional hortus conclusus in the image of the nineteenth-century artistic mind. -

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland

Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Woonakkoord Oost Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland Met trots bieden we u het Woonakkoord Oost-Nederland aan en nodigen het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties uit samen hieraan verder te bouwen. Een akkoord dat de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen, de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede en de provincies Overijssel en Gelderland met het Rijk willen sluiten. We zijn blij dat het Rijk de grote urgentie van de woningbouwopgave in Oost-Nederland ziet en daar met ons op verder wil bouwen. We willen in genoemde steden en regio’s in de komende 5 jaar 75.000 woningen bijbouwen voor starters, doorstromers en alleenstaanden. We zijn bereid om naar innovatieve en flexibele bouwwijzen en verstedelijking te kijken om snel en slim mensen van een huis te voorzien. De Randstad verschuift naar het Oosten Alleen al vanuit de Randstad verwachten we de komende 5 jaar zo’n 60.000 nieuwe huishoudens in het oosten. De verhuisstroom uit de Randstad zorgt voor een snelle verstedelijking in onze steden. Er is nog steeds een grote verhuisstroom naar de Randstad, maar dat zijn vooral jonge mensen die geen huis achter laten. De nieuwkomers vanuit de Randstad zijn vooral gezinnen en ouderen die een nieuwe woning zoeken. We delen de grote woonopgave op in een woondeal voor de steden Arnhem en Nijmegen waar de woningnood het meest urgent is en een verstedelijkingsstrategie voor de regio’s Zwolle-Deventer- Enschede en Arnhem-Nijmegen-FoodValley/Ede. Met aandacht voor de bereikbaarheid van de steden en binnen de steden. Het gaat daarbij niet alleen om weg-, spoor- en fietsverbindingen, maar ook om nieuwe vormen van mobiliteit. -

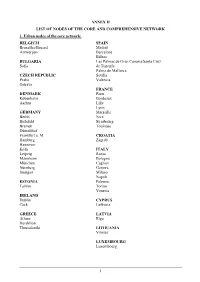

Annex Ii List of Nodes of the Core and Comprehensive Network 1

ANNEX II LIST OF NODES OF THE CORE AND COMPREHENSIVE NETWORK 1. Urban nodes of the core network: BELGIUM SPAIN Bruxelles/Brussel Madrid Antwerpen Barcelona Bilbao BULGARIA Las Palmas de Gran Canaria/Santa Cruz Sofia de Tenerife Palma de Mallorca CZECH REPUBLIC Sevilla Praha Valencia Ostrava FRANCE DENMARK Paris København Bordeaux Aarhus Lille Lyon GERMANY Marseille Berlin Nice Bielefeld Strasbourg Bremen Toulouse Düsseldorf Frankfurt a. M. CROATIA Hamburg Zagreb Hannover Köln ITALY Leipzig Roma Mannheim Bologna München Cagliari Nürnberg Genova Stuttgart Milano Napoli ESTONIA Palermo Tallinn Torino Venezia IRELAND Dublin CYPRUS Cork Lefkosia GREECE LATVIA Athina Rīga Heraklion Thessaloniki LITHUANIA Vilnius LUXEMBOURG Luxembourg 1 HUNGARY SLOVENIA Budapest Ljubljana MALTA SLOVAKIA Valletta Bratislava THE NETHERLANDS FINLAND Amsterdam Helsinki Rotterdam Turku AUSTRIA SWEDEN Wien Stockholm Göteborg POLAND Malmö Warszawa Gdańsk UNITED KINGDOM Katowice London Kraków Birmingham Łódź Bristol Poznań Edinburgh Szczecin Glasgow Wrocław Leeds Manchester PORTUGAL Portsmouth Lisboa Sheffield Porto ROMANIA București Timişoara 2 2. Airports, seaports, inland ports and rail-road terminals of the core and comprehensive network Airports marked with * are the main airports falling under the obligation of Article 47(3) MS NODE NAME AIRPORT SEAPORT INLAND PORT RRT BE Aalst Compr. Albertkanaal Core Antwerpen Core Core Core Athus Compr. Avelgem Compr. Bruxelles/Brussel Core Core (National/Nationaal)* Charleroi Compr. (Can.Charl.- Compr. Brx.), Compr. (Sambre) Clabecq Compr. Gent Core Core Grimbergen Compr. Kortrijk Core (Bossuit) Liège Core Core (Can.Albert) Core (Meuse) Mons Compr. (Centre/Borinage) Namur Core (Meuse), Compr. (Sambre) Oostende, Zeebrugge Compr. (Oostende) Core (Oostende) Core (Zeebrugge) Roeselare Compr. Tournai Compr. (Escaut) Willebroek Compr. BG Burgas Compr. -

Viral and Bacterial Infection Elicit Distinct Changes in Plasma Lipids in Febrile Children

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/655704; this version posted May 31, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Viral and bacterial infection elicit distinct changes in plasma lipids in febrile children 2 Xinzhu Wang1, Ruud Nijman2, Stephane Camuzeaux3, Caroline Sands3, Heather 3 Jackson2, Myrsini Kaforou2, Marieke Emonts4,5,6, Jethro Herberg2, Ian Maconochie7, 4 Enitan D Carrol8,9,10, Stephane C Paulus 9,10, Werner Zenz11, Michiel Van der Flier12,13, 5 Ronald de Groot13, Federico Martinon-Torres14, Luregn J Schlapbach15, Andrew J 6 Pollard16, Colin Fink17, Taco T Kuijpers18, Suzanne Anderson19, Matthew Lewis3, Michael 7 Levin2, Myra McClure1 on behalf of EUCLIDS consortium* 8 1. Jefferiss Research Trust Laboratories, Department of Medicine, Imperial College 9 London 10 2. Section of Paediatrics, Department of Medicine, Imperial College London 11 3. National Phenome Centre and Imperial Clinical Phenotyping Centre, Department of 12 Surgery and Cancer, IRDB Building, Du Cane Road, Imperial College London, 13 London, W12 0NN, United Kingdom 14 4. Great North Children’s Hospital, Paediatric Immunology, Infectious Diseases & 15 Allergy, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon 16 Tyne, United Kingdom. 17 5. Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 18 Kingdom 19 6. NIHR Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre based at Newcastle upon Tyne 20 Hospitals NHS Trust and Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, United 21 Kingdom 22 7. Department of Paediatric Emergency Medicine, St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College 23 NHS Healthcare Trust, London, United Kingdom 24 8. -

Hortus Conclusus: a Visual Discourse Analysis Based on a Critical Literacy Approach to Education

UDC 378.147::811.111](497.11) Milica Stojanović University of Belgrade, Serbia HORTUS CONCLUSUS: A VISUAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS BASED ON A CRITICAL LITERACY APPROACH TO EDUCATION Abstract Some form of critical literacy seems to have become essential to all students today, irrespective of where they are studying, at what level, or what their academic field is. Indeed, in even greater need of developing their critical literacy abilities appear to be students of the Humanities for it is in these areas of study that some critical, cultural and historical perspectives are constantly being re-examined, reassessed, deconstructed and reconstructed in accordance with our age/postmodern/modern theories. By way of illustration, and taking as its premise the assumption that all knowledge is, at least to a certain extent, ideological and related to power, this paper attempts, within the theoretical framework of critical literacy, an analysis of a specific visual discourse relevant to art history studies – the iconography of Hortus Conclusus (Enclosed Garden). Methodologically speaking, the benefits from this kind of approach could be manifold. Students are and feel empowered to critically acquire/deconstruct/reconstruct knowledge in specific content areas – a fact which in itself provides higher motivation in an EAP class (they are primarily focused on gaining knowledge in English rather than that of/about English). All the stages of the above demonstrated process are conducted in English, which gives the teacher an excellent opportunity to cater for the students’ specific needs (e.g. employ concept and semantic mapping and other vocabulary-building strategies relevant to their fields of study). -

Sensory Reality As Perceived Through the Religious Iconography of the Renaissance

Sensory reality as perceived through the religious iconography of the Renaissance Maria Athanasekou, Athens In Della pittura, Leon Battista Alberti wrote: “No one would deny that the painter has nothing to do with things that are not visible. The painter is concerned solely with representing what can be seen.”1 What Alberti does not mention is that during the Trecento, as well as in his own time, painted surfaces were populated with things that are not visible, with saints and angels, seraphims and cherubims, even the Madonna, Jesus and the Almighty God. The reality of all religious paintings of the Renaissance is virtually inhabited by heavenly and otherworldly creatures, taking the viewer onto a metaphysical level of experience and mystical union with the celestial cosmos. Physical space is intertwined with the supernatural environment that holy fig- ures occupy, and religious paintings systematically form another ac- tuality, a virtual reality for the viewer to experience and sense. In most cases this dynamic new world is the result of the com- bined efforts of the artist and the client (or patron), as specific details regarding the execution, content, materials, cost and time of delivery were stipulated in contracts. Hence, the scenographic virtuality of sa- cred images was produced by real people who wished to construct an alternative sensory reality in which they are portrayed alongside holy men and women. During the period ranging from the later Middle Ages to the end of the seventeenth century, Europeans believed that their heads contained three ventricles. In these, they were told, their faculties were processed, circulated and stored the sensory 1 Alberti 1967, 43.