Jul 12 2010 Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Pacific Garbage Patch,' in Name of Research 4 August 2009, by Paul Rogers

Scientists ready to set sail for 'Great Pacific Garbage Patch,' in name of research 4 August 2009, By Paul Rogers Hoping to learn more about one of the most glaring sail for a 30-day voyage from San Francisco. examples of waste and environmental pollution on Earth, a group of scientists will set sail from San The other ship, the 170-foot New Horizon, owned Francisco Tuesday to the "Great Pacific Garbage by the University of California-San Diego, left Patch," a massive vortex of floating plastic trash Southern California on Sunday. It has a crew of estimated by some researchers to be twice the about 20 people, many of them graduate students size of Texas. in marine biology, funded by a $600,000 grant from the University of California. The bobbing debris field, where currents swirl everything from discarded fishing line to plastic Both ships will study the Garbage Patch's size, how bottles into one soupy mess, is located about the plastic affects wildlife, and whether it may be 1,000 miles west of California. possible to clean some of it up. "This is a problem that is kind of out of sight, out of "We are going to try to target the highest plastic mind, but it is having devastating impacts on the areas we see to begin to understand the scope of ocean. I felt we needed to do something about it," the problem," said Miriam Goldstein, chief scientist said Mary Crowley, co-founder of Project Kaisei, a of the Scripps expedition. "The team of graduate non-profit expedition that is partnering on the students will be studying everything from voyage with the Scripps Institution of phytoplankton to zooplankton to small midwater Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif. -

Pressions of Volcanic Rock Outcrops, in Situ Ments Sampled from Kamilo Beach

Kelly Jazvac Rock Record September 9 – October 15, 2017 FIERMAN presents Rock Record, a solo exhibition by Canadian artist Kelly Jazvac. Rock Record features found materials presented both as art objects and as scientific evidence that plastic pollution has irrevocably changed Earth. The show centers on plastiglomerate – a term collaboratively coined by Jazvac, geologist Patricia Corcoran, and oceanographer Charles Moore in 2013—a new type of stone first described on Kamilo Beach, Hawaii, and later identified on beaches around the globe. Plastiglomerate is a hybrid stone produced when plastic debris melts and fuses with naturally-found sediment such as sand, shells, rock, and wood. For several years, Jazvac has presented these stones in art galleries and museums, emphasizing their poetic, affective, and pedagogical potential. Through their simultaneously natural and artificial forms, each plastiglomerate works to visualize the dense entanglements of human consumption and the environments that adapt and react to our overwhelming presence. However, these stones are not simply, nor primarily, artworks. They are also scientific evidence of how anthropogenic materials are altering Earth’s geology, as explained by Jazvac, Corcoran, and Moore in a co-authored scientific paper published in 2014. They argue that plastiglomerate has the potential to sink into Earth’s strata: due to the increased density of this plastic-sediment fusion, as plastiglomerate becomes buried, so too will the material be preserved for centuries to come. Both Corcoran and Jazvac are founding members of an interdisciplinary research team that considers the ways in which art and culture can contribute to scientific research. This team works collaboratively to make largely unseen aspects of plastic pollution visible. -

Trash Travels: the Truth—And the Consequences

From Our Hands to the Sea, Around the Globe, and Through Time Contents Overview introduction from the president and ceo . 02 a message from philippe cousteau . 03 executive summary . 04 results from the 2009 international coastal cleanup . 06 participating countries map . .07 trash travels: the truth—and the consequences . 16 the pacific garbage patch: myths and realities . 24 international coastal cleanup sponsoring partners . .26 international coastal cleanup volunteer coordinators and sponsors . 30 The Marine Debris Index terminology . 39 methodology and research notes . 40 marine debris breakdown by countries and locations . 41 participation by countries and locations . 49 marine debris breakdown by us states . 50 participation by us states . 53. acknowledgments and photo credits . 55. sources . 56 Ocean Conservancy The International Coastal Cleanup Ocean Conservancy promotes healthy and diverse In partnership with volunteer organizations and ecosystems and opposes practices that threaten individuals across the globe, Ocean Conservancy’s ocean life and human life. Through research, International Coastal Cleanup engages people education, and science-based advocacy, Ocean to remove trash and debris from the world’s Conservancy informs, inspires, and empowers beaches and waterways, to identify the sources people to speak and act on behalf of the ocean. of debris, and to change the behaviors that cause In all its work, Ocean Conservancy strives to be marine debris in the first place. the world’s foremost advocate for the ocean. © OCEAN CONSERVANCY . ALL RIGHTS RESERVED . ISBN: 978-0-615-34820-9 LOOKING TOWARD THE 25TH ANNIVERSARY INTERNATIONAL COASTAL CLEANUP ON SEPTEMBER 25, 2010, Ocean Conservancy 01 is releasing this annual marine debris report spotlighting how trash travels to and throughout the ocean, and the impacts of that debris on the health of people, wildlife, economies, and ocean ecosystems. -

SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 the Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011

PICES SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011 Editors: Cathryn Clarke Murray, Thomas W. Therriault, Hideaki Maki, and Nancy Wallace Authors: Stephen Ambagis, Rebecca Barnard, Alexander Bychkov, Deborah A. Carlton, James T. Carlton, Miguel Castrence, Andrew Chang, John W. Chapman, Anne Chung, Kristine Davidson, Ruth DiMaria, Jonathan B. Geller, Reva Gillman, Jan Hafner, Gayle I. Hansen, Takeaki Hanyuda, Stacey Havard, Hirofumi Hinata, Vanessa Hodes, Atsuhiko Isobe, Shin’ichiro Kako, Masafumi Kamachi, Tomoya Kataoka, Hisatsugu Kato, Hiroshi Kawai, Erica Keppel, Kristen Larson, Lauran Liggan, Sandra Lindstrom, Sherry Lippiatt, Katrina Lohan, Amy MacFadyen, Hideaki Maki, Michelle Marraffini, Nikolai Maximenko, Megan I. McCuller, Amber Meadows, Jessica A. Miller, Kirsten Moy, Cathryn Clarke Murray, Brian Neilson, Jocelyn C. Nelson, Katherine Newcomer, Michio Otani, Gregory M. Ruiz, Danielle Scriven, Brian P. Steves, Thomas W. Therriault, Brianna Tracy, Nancy C. Treneman, Nancy Wallace, and Taichi Yonezawa. Technical Editor: Rosalie Rutka Please cite this publication as: The views expressed in this volume are those of the participating scientists. Contributions were edited for Clarke Murray, C., Therriault, T.W., Maki, H., and Wallace, N. brevity, relevance, language, and style and any errors that [Eds.] 2019. The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the were introduced were done so inadvertently. Great Japan Tsunami of 2011, PICES Special Publication 6, 278 pp. Published by: Project Designer: North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES) Lori Waters, Waters Biomedical Communications c/o Institute of Ocean Sciences Victoria, BC, Canada P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, BC, Canada V8L 4B2 Feedback: www.pices.int Comments on this volume are welcome and can be sent This publication is based on a report submitted to the via email to: [email protected] Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, in June 2017. -

Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Biology Faculty Publications Biology 11-11-2016 Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i Alan M. Young Salem State University James A. Elliott Salem State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/biology_facpub Part of the Biology Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Young, Alan M. and Elliott, James A., "Characterization of Microplastic and Mesoplastic Debris in Sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i" (2016). Biology Faculty Publications. 1. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/biology_facpub/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. Marine Pollution Bulletin 113 (2016) 477–482 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Pollution Bulletin journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marpolbul Note Characterization of microplastic and mesoplastic debris in sediments from Kamilo Beach and Kahuku Beach, Hawai'i Alan M. Young ⁎, James A. Elliott Biology Department, Salem State University, 352 Lafayette Street, Salem, MA 01970, United States article info abstract Article history: Sediment samples were collected from two Hawai'ian beaches, Kahuku Beach on O'ahu and Kamilo Beach on the Received 21 September 2016 Big Island of Hawai'i. A total of 48,988 large microplastic and small mesoplastic (0.5–8 mm) particles were Received in revised form 7 November 2016 handpicked from the samples and sorted into four size classes (0.5–1 mm, 1–2 mm, 2–4mm,4–8 mm) and Accepted 9 November 2016 nine color categories. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Gyre Plastic : Science, Circulation and the Matter of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/21w9h64q Author De Wolff, Kim Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Gyre Plastic: Science, Circulation and the Matter of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Communication by Kim De Wolff Committee in charge: Professor Chandra Mukerji, Chair Professor Joseph Dumit Professor Kelly Gates Professor David Serlin Professor Charles Thorpe 2014 Copyright Kim De Wolff, 2014 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Kim De Wolff is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ........................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ....................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................ vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... ix Vita ............................................................................................................................ -

President's Corner Congressional News Ocean Leadership News

1201 New York Avenue, NW z Fourth Floor z Washington, DC 20005 P: (202) 232-3900 z F: (202) 462-8754 z www.OceanLeadership.org Please add [email protected] to your personal address book to ensure delivery. To subscribe, unsubscribe, or change the preferences on your subscriptions to Ocean Leadership emails, please use the following link: http://lists.oceanleadership.org/mailman/listinfo. President’s Corner Congressional News • Senate Committee Discusses Reauthorization of the Chesapeake Bay Program • Senate Markup of Geospatial, Hypoxia Legislation Ocean Leadership News • NOPP Announces $20 Million in Research Grants • ORRAP Meeting Next Week in Washington, DC • The Great Marlin Race is Underway • Faculty Professional Development Opportunity at GSA Ocean Community News • Ocean Sciences 2010 Session: Ocean Technology and Infrastructure Needs for the Next 20 Years • Thinning Cloud Cover Over Oceans Speeds Global Warming • Fish Discovered With Light Sensing Cells • Proposed Algal Biofuel Pilot Facility • Scientists Probe Great Pacific Garbage Patch • Interdisciplinary Climate Change Research Symposium • Application Process For Cohort VII of the MS PHD’s Professional Development Program Now Open • Ridge 2000 Integration & Synthesis Workshop • NOAA and NSF Call For Proposals • Antarctic Climate Evolution Symposium in September • NSF Grant Proposal Deadline: August 15, 2009 Job Announcements To access the job announcements page, go to http://www.oceanleadership.org/about/employment. No new opportunities this week. Calendar of Events President’s Corner The President’s Corner will return next week. Congressional News SENATE COMMITTEE DISCUSSES REAUTHORIZATION OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY PROGRAM In a Senate Environment and Public works hearing on Monday a panel of agency and industry representatives voiced their support for the reauthorization of the Chesapeake Bay Program, including suggestions to expand federal and state authority, increase funding, and incorporate accountability mechanisms. -

MARINE LITTER SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY FINAL VERSION: DECEMBER 2017 Recommended Citation: UN Environment (2017)

MARINE LITTER SOCIO-ECONOMIC STUDY FINAL VERSION: DECEMBER 2017 Recommended citation: UN Environment (2017). Marine Litter Socio Economic Study, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. Kenya. Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment), 2017 ISBN No: 978-92-807-3701-1 Job No: DEP/2175/NA No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Communication Division, UN Environment P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, Kenya, [email protected]. The Government of Germany is gratefully acknowledged for providing the necessary funding that made the production of this publication “Marine Litter Socio Economic Study“ possible. Acknowledgements: Peer reviewers: Dr. Sarah Dudas (Vancouver Island University), Dr. Jesús Gago (Instituto Español de Oceanografía), Francois Galgani (IFREMER), Dr. Denise Hardesty (CSIRO), Gaëlle Haut (Surfrider Foundation), Heidi Savelli (UN Environment), Dr. Sunwook Hong (OSEAN), Dr. Peter Kershaw (GESAMP), Ross A. Klein (Cruise Junkie/ Memorial University of Newfoundland), Päivi Munne (Finnish Environment Institute), Dr. Sabine Pahl (Plymouth University), François Piccione (Surfrider Foundation), Emma Priestland (Seas at Risk), Jacinthe Séguin (Environment Canada), Kaisa Uusimaa (UN Environment) , Dr. Dick Vethaak (Deltares), Nancy Wallace (NOAA Federal) -

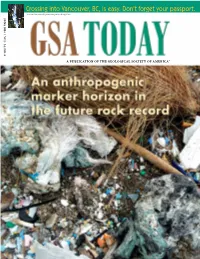

Crossing Into Vancouver, BC, Is Easy. Don't Forget Your Passport

Crossing into Vancouver, BC, is easy. Don’t forget your passport. Tourism Vancouver / Capilano Suspension Bridge Park. JUNE | VOL. 24, 2014 6 NO. A PUBLICATION OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA® JUNE 2014 | VOLUME 24, NUMBER 6 Featured Article GSA TODAY (ISSN 1052-5173 USPS 0456-530) prints news and information for more than 26,000 GSA member readers and subscribing libraries, with 11 monthly issues (April/ May is a combined issue). GSA TODAY is published by The SCIENCE: Geological Society of America® Inc. (GSA) with offices at 3300 Penrose Place, Boulder, Colorado, USA, and a mail- 4 An anthropogenic marker horizon in the future ing address of P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA. rock record GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, Patricia L. Corcoran, Charles J. Moore, and regardless of race, citizenship, gender, sexual orientation, Kelly Jazvac religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Cover: Plastiglomerate fragments interspersed with plastic debris, © 2014 The Geological Society of America Inc. All rights organic material, and sand on Kamilo Beach, Hawaii. Photo by K. Jazvac. reserved. Copyright not claimed on content prepared See related article, p. 4–8. wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or request to GSA, to use a single figure, table, and/or brief paragraph of text in subsequent work and to make/print unlimited copies of items in GSA TODAY for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Abundance and Ecological

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Abundance and ecological implications of microplastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Oceanography by Miriam Chanita Goldstein Committee in charge: Professor Mark D. Ohman, Chair Professor Lihini I. Aluwihare Professor Brian Goldfarb Professor Michael R. Landry Professor James J. Leichter 2012 Copyright Miriam Chanita Goldstein, 2012 All rights reserved. SIGNATURE PAGE The Dissertation of Miriam Chanita Goldstein is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: PAGE _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION For my mother, who took me to the tidepools and didn’t mind my pet earthworms. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE ................................................................................................... iii DEDICATION ............................................................................................................. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES -

Great Pacific Garbage Patch from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 38°N 145°W Great Pacific garbage patch From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Pacific garbage patch, also described as the Pacific trash vortex, is a gyre of marine debris particles in the central North Pacific Ocean discovered between 1985 and 1988. It is located roughly between 135°W to 155°W and 35°N and 42°N.[1] The patch extends over an indeterminate area, with estimates ranging very widely depending on the degree of plastic concentration used to define the affected area. The patch is characterized by exceptionally high relative concentrations of pelagic plastics, chemical sludge and other debris that have been trapped by the currents of the North Pacific Gyre.[2] Because of its large area, it is of very low density (4 particles per cubic meter), and therefore not visible from satellite photography, nor even necessarily to casual boaters or divers in the area. It consists primarily of a small increase in suspended, often microscopic, particles in the upper water column. Contents The area of increased plastic particles is located within the North Pacific Gyre, one of the five major oceanic gyres. 1 Discovery 2 Formation 3 Estimates of size 4 Photodegradation of plastics 5 Effect on wildlife and humans Visualisation showing ocean garbage patches. 6 Controversy 7 Cleanup research 7.1 2008 7.2 2009 7.3 2012 7.4 2013 7.5 2015 7.6 2016 8 See also 9 References 10 Further reading 11 External links Discovery The great Pacific garbage patch was described in a 1988 paper published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States. -

Written Testimony of Nicholas J. Mallos, Director, Trash Free Seas®, Ocean Conservancy Before the United States Senate Environm

Written Testimony of Nicholas J. Mallos, Director, Trash Free Seas®, Ocean Conservancy Before The United States Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Subcommittee on Fisheries, Water and Wildlife of the Environment and Public Works Hearing on Marine Debris and Wildlife: Impacts, Sources and Solutions May 17, 2016 Good morning. Thank you for inviting me to speak with you about the preponderance of plastics that are gathering in our seas and on our coastlines, affecting fisheries, marine mammals and potentially human health. My name is Nicholas Mallos, and I am director of Ocean Conservancy’s Trash Free Seas® program. Ocean Conservancy works across sectors, bringing businesses, conservationists and governments together to address systemic challenges and find lasting solutions. In all we do, we work with a range of partners to find scalable, implementable solutions that make a difference for the ocean and the communities that depend upon it. Ocean Conservancy is supported by a diverse funding base that currently includes individual donors, public and private foundations, corporations and U.S. government support. Plastic debris exists in every region of the ocean from consumer products floating in the ocean’s five major gyres to fibers buried in deep sea sediments and from microplastics embedded in Arctic sea ice to a wide diversity of plastics found on beaches worldwide. Today, I intend to convey the need for a new, interdisciplinary research agenda to better explain the scale and scope of the impact of plastics on marine ecosystems so that better-informed policies can confront these risks. Advancing this science requires a funding commitment from decision-makers who recognize that controlling plastic inputs to ocean ecosystems is a necessary condition for the ocean to provide the services upon which we depend.