Interview with John Borling # VRV-A-L-2013-037.01 Interview # 01: May 29, 2013 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Defense - Military Base Realignments and Closures (1)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON October 31, 197 5 MEMORANDUM TO: JACK MARSH FROM: RUSS ROURKE I discussed the Ft. Dix situation with Rep. Ed Forsythe again. As you may know, I reviewed the matter with Marty Hoffman at noon yesterday, and with Col. Kenneth Bailey several days ago. Actually, I exchanged intelligence information with him. Hoffman and Bailey advised me that no firm decision has as yet been made with regard to the retention of the training function at Dix. On Novem ber 5, Marty Hotfman will receive a briefing by Army staff on pos sible "back fill'' organizations that may be available to go to Dix in the event the training function moves out. -

Evaluation of Fighter Evasive Maneuvers Against Proportional Navigation Missiles

TURKISH NAVAL ACADEMY NAVAL SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING INSTITUTE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER ENGINEERING MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAM IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING EVALUATION OF FIGHTER EVASIVE MANEUVERS AGAINST PROPORTIONAL NAVIGATION MISSILES Master Thesis REMZ Đ AKDA Ğ Advisor: Assist.Prof. D.Turgay Altılar Đstanbul, 2005 Copyright by Naval Science and Engineering Institute, 2005 CERTIFICATE OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL EVALUATION OF FIGHTER EVASIVE MANEUVERS AGAINST PROPORTIONAL NAVIGATION MISSILES Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING from the TURKISH NAVAL ACADEMY Author: Remzi Akda ğ Defense Date : 13 / 07 / 2005 Approved by : 13 / 07 / 2005 Assist.Prof. Deniz Turgay Altılar (Advisor) Prof. Ercan Öztemel (Defense Committee Member) Assoc.Prof. Coşkun Sönmez (Defense Committee Member) ABSTRACT (TURKISH) SAVA Ş UÇAKLARININ ORANTISAL SEY ĐR YAPAN GÜDÜMLÜ MERM ĐLERDEN SAKINMA MANEVRALARININ DE ĞERLEND ĐRĐLMES Đ Anahtar Kelimeler : Orantısal seyir, sakınma manevraları, aerodinamik kuvvetler Bu tezde, orantısal seyir adı verilen güdüm sistemiyle ilerleyen güdümlü mermilere kar şı uçaklar tarafından icra edilen sakınma manevralarının etkinli ği ölçülmü ş, farklı güdümlü mermilerden kaçı ş için en uygun manevralar tanımlanmı ştır. Uçu ş aerodinamikleri, matematiksel modele bir temel oluşturmak amacıyla sunulmu ştur. Bir hava sava şında güdümlü mermilerden sakınmak için uçaklar tarafından icra edilen belli ba şlı manevraların matematiksel modelleri çıkarılıp uygulanılmı ş, görsel simülasyonu gerçekle ştirilmi ş ve bu manevraların de ğişik ba şlangıç de ğerlerine göre ba şarım çözümlemeleri yapılmıştır. Güdümlü mermi-uçak kar şıla şma senaryolarında güdümlü merminin terminal güdüm aşaması ele alınmı ştır. Gerçekçi çözümleme sonuçları elde edebilmek amacıyla uçu ş aerodinamiklerinin göz önüne alınmasıyla elde edilen yönlendirme kinematiklerini içeren geni şletilmi ş nokta kütleli uçak modeli kullanılmı ştır. -

Episode 711, Story 1: Stalag 17 Portrait Eduardo

Episode 711, Story 1: Stalag 17 Portrait Eduardo: Our first story looks at a portrait made by an American POW in a World War Two German prison camp. 1943, as American air attacks against Germany increase; the Nazis move the growing number of captured American airmen into prisoner of war camps, called Stalags. Over 4,000 airmen ended up in Stalag 17-b, just outside of Krems, Austria, in barracks made for 240 men. How did these men survive the deprivation and hardships of one of the most infamous prisoner of war camps of the Nazi regime? 65 years after her father George Silva became a prisoner of war, Gloria Mack of Tempe, Arizona has this portrait of him drawn by another POW while they were both prisoners in Stalag 17-b. Gloria: I thought what a beautiful thing to come out of the middle of a prison camp. Eduardo: Hi, I’m Eduardo Pagan from History Detectives. Gloria: Oh, it’s nice to meet you. Eduardo: It’s nice to meet you, too! Gloria: Come on in. Eduardo: Thank you. I’M curious to see Gloria’s sketch, and hear her father’s story. It’s a beautiful portrait. When was this portrait drawn? Gloria: It was drawn in 1944. 1 Eduardo: How did you learn about this story of how he got this portrait? Gloria: Because of this little story on the back. It says, “Print from an original portrait done in May of 1944 by Gil Rhoden. We were POW’s in Stalag 17 at Krems, Austria. -

Newsletter Still Doesn't Have Any Reporting on Direct Queries and Submissions To: Recent Developments in U.S

N ewsletter NoVEMbER, 1991 VolUME 5 NuMbER 5 SpEciAl JournaL Issue In This Issue................................................................ 2 The Speed of DAnksess ancI "CrazecJ V ets on tHe oorstep rama e o s e PublJshER's S tatement, by Ka U TaL .............................5 D D ," by DAvId J. D R ...............40 REMF Books, by DAvid WHLs o n .............................. 45 A nnouncements, Notices, & Re p o r t s ......................... 4 eter C ortez In DarIen, by ALan FarreU ........................... 22 PoETRy, by P D ssy............................................4 4 FIctIon: Hie Romance of Vietnam, VoIces fROM tHe Past: TTie SearcTi foR Hanoi HannaK by RENNy ChRlsTophER...................................... 24 by Don NortTi ...................................................44 A FiREbAlL In tBe Nlqlrr, by WHUam M. KiNq...........25 H ollyw ood CoNfidENTlAl: 1, b y FREd GARdNER........ 50 Topics foR VJetnamese-U.S. C ooperation, PoETRy, by DennIs FRiTziNqER................................... 57 by Tran Qoock VuoNq....................................... 27 Ths A ll CWnese M ercenary BAskETbAll Tournament, Science FIctIon: This TIme It's War, by PauI OLim a r t ................................................ 57 by ALascIaIr SpARk.............................................29 (Not Much of a) War Story, by Norman LanquIst ...59 M y Last War, by Ernest Spen cer ............................50 Poetry, by Norman LanquIs t ...................................60 M etaphor ancI War, by GEORqE LAkoff....................52 A notBer -

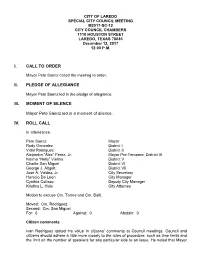

I. Call to Order Ii. Pledge of Allegiance Iii

CITY OF LAREDO SPECIAL CITY COUNCIL MEETING M2017-SC-12 CITY COUNCIL CHAMBERS 1110 HOUSTON STREET LAREDO, TEXAS 78040 December 12, 2017 12:00 P.M. I. CALL TO ORDER Mayor Pete Saenz called the meeting to order. II. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Mayor Pete Saenz led in the pledge of allegiance. III. MOMENT OF SILENCE Mayor Pete Saenz led in a moment of silence. IV. ROLL CALL In attendance: Pete Saenz Mayor Rudy Gonzalez District I Vidal Rodriguez District II Alejandro “Alex” Perez, Jr. Mayor Pro-Tempore, District III Norma “Nelly” Vielma District V Charlie San Miguel District VI George J. Altgelt District VII Jose A. Valdez, Jr. City Secretary Horacio De Leon City Manager Cynthia Collazo Deputy City Manager Kristina L. Hale City Attorney Motion to excuse Cm. Torres and Cm. Balli. Moved: Cm. Rodriguez Second: Cm. San Miguel For: 6 Against: 0 Abstain: 0 Citizen comments Ivan Rodriguez stated his value in citizens’ comments at Council meetings. Council and citizens should adhere a little more closely to the rules of procedure, such as time limits and the limit on the number of speakers for any particular side to an issue. He noted that Mayor Saenz, as the Chair of Council meetings, should exercise his role to prevent speakers going over their time and unnecessarily lengthy discussion. He objected to moving public comments to any place on the Council agenda other than the beginning as it would prevent Council from receiving public opinion before they make their decisions. Barry Bernier noted that misinformation has been given to Council regarding the wishes of Laredo veterans. -

Update on the F–35 Joint Strike Fighter Program

i [H.A.S.C. No. 114–58] UPDATE ON THE F–35 JOINT STRIKE FIGHTER PROGRAM HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TACTICAL AIR AND LAND FORCES OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION HEARING HELD OCTOBER 21, 2015 U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 97–492 WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 SUBCOMMITTEE ON TACTICAL AIR AND LAND FORCES MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio, Chairman FRANK A. LOBIONDO, New Jersey LORETTA SANCHEZ, California JOHN FLEMING, Louisiana NIKI TSONGAS, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER P. GIBSON, New York HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, JR., Georgia PAUL COOK, California TAMMY DUCKWORTH, Illinois BRAD R. WENSTRUP, Ohio MARC A. VEASEY, Texas JACKIE WALORSKI, Indiana TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota SAM GRAVES, Missouri DONALD NORCROSS, New Jersey MARTHA MCSALLY, Arizona RUBEN GALLEGO, Arizona STEPHEN KNIGHT, California MARK TAKAI, Hawaii THOMAS MACARTHUR, New Jersey GWEN GRAHAM, Florida WALTER B. JONES, North Carolina SETH MOULTON, Massachusetts JOE WILSON, South Carolina JOHN SULLIVAN, Professional Staff Member DOUG BUSH, Professional Staff Member NEVE SCHADLER, Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Page STATEMENTS PRESENTED BY MEMBERS OF CONGRESS Turner, Hon. Michael R., a Representative from Ohio, Chairman, Subcommit- tee on Tactical Air and Land Forces .................................................................. 1 WITNESSES Bogdan, Lt Gen Christopher C., USAF, Program Executive Officer, F–35 Joint Program Office, U.S. Department of Defense .......................................... 2 Harrigian, Maj Gen Jeffrey L., USAF, Director, F–35 Integration Office, U.S. -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

Autonomous Aerobatics: a Linear Algorithm and Implementation for a Slow Roll Student: Michael Brett Pearce1 Professors: Dr

Autonomous Aerobatics: A Linear Algorithm and Implementation for a Slow Roll Student: Michael Brett Pearce1 Professors: Dr. Larry Silverberg2, Dr. Ashok Golpalarathnam3, Dr. Gregory Buckner4 Technical Expert on Aerobatics: John White, Master Aerobatic Instructor 2061858 CFI5 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Introduction Control Algorithm Methodology Custom Designed Airframe Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles ( ’s) are becoming common on the battlefield airspace but to date UCAV 1.21:1 Thrust to Twin Rudders for Yaw A pilot is essentially a PID Controller. The author’s unique aviation Control they have not been implemented in fighters due to the complexity of executing maneuvers required and VF-1 Valkyrie Weight Ratio the nonlinearities in aerodynamics, control response, control inputs required, and extreme attitudes. experience as a Certificated Flight Instructor and competition aerobatic pilot Custom Designed for project requirements Flapperons for Split Elevons for Thrust in powered and sailplanes is applied and converted to a mathematical basis. Hyper maneuverable aerobatic airframe with Slow Speed Flight Vectoring Such maneuvers are crucial for , low level penetration Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM, “dogfighting”) full 3-axis thrust vectoring with extreme maneuvering for bombing targets, escape and evasion from missiles, and "jinking" for This reduces the control problem to a linear system, bypassing the analytical, Capable of unlimited aerobatics and post stall avoiding ground to air gunfire. Such flying is collectively known as Basic Fighter Maneuvers (BFM). maneuvering computational, and monetary issues with a typical engineering approach. Onboard autopilot in a custom chassis BFM is fundamentally composed of aerobatics, and aerobatics itself is fundamentally composed of a few Foam core composite airframe stressed for in basic maneuvers. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

The Vietnam Press: the Unrealised Ambition

Edith Cowan University Research Online ECU Publications Pre. 2011 1995 The Vietnam press: the unrealised ambition Frank Palmos Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Palmos, F. (1995). The Vietnam press: The unrealised ambition. Mount Lawley, Australia: The Centre for Asian Communication, Media and Cultural Studies, Edith Cowan University. This Book is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/6774 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Reporting Asia Series The Vietnam Press: The Unrealised Ambition Frank Palmos Centre for Asian Communication, Media and Cultural Studies Director and Series Editor - Dr. Brian Shoesmith Faculty of Arts Edith Cowan University Western Austi·alia © 1995 Reporting Asia Series Published by - The Centre for Asian Communication, Media and Cultural Studies. Director and Series Editor- Dr Brian Shoesmith Faculty of Arts Edith Cowan University 2 Bradford Street Mount Lawley Western Australia. -

"Vive L'angleterre": Exploring the Relationship Between Britain And

“Vive l’Angleterre” Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand A Thesis Presented to The Department of Literature, Area Studies and European Languages University of Oslo In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the MA Degree Spring 2015 ii “Vive l’Angleterre” Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand iii © Sunniva Sveino Strand 2015 “Vive l’Angleterre”: Exploring the Relationship between Britain and Europe in Charlotte Brontë’s Novels Sunniva Sveino Strand http://www.duo.uio.no Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo iv Abstract The purpose of this thesis is to explore the complex relationship Charlotte Brontë’s novels have with Europe. It will examine how religion, sexuality and morality, and language are used in order to create a British identity that is contrasted to a European one, but also how these binaries are broken down via the romantic unions of British and European characters and the appeal of certain aspects of Catholicism, European sexuality and the French language. The role of Europe has often been overlooked in favour of the British Empire in Brontë scholarship, and this thesis posits that Europe is integral to the establishment of a British national identity in Brontë’s works. Furthermore, those who have studied the author’s presentation of Europe have often limited themselves to the two novels that are set on the Continent, but I argue that much is lost in disregarding the remainder of Brontë’s works. The findings of this thesis suggest that despite the rampant Europhobia found in Brontë’s works, these novels stand out amongst their contemporaries in envisaging romantic unions between Britons and Europeans and that the British characters need something, or someone, European in order to be fulfilled. -

Everett Pratt Transcript.Pdf

Everett H. Pratt Jr. Part 1 Nov. 2, 2016 Interviewed by John Schwan Transcribed by Unknown Edited by Alex Swanson [02:37.36] Interview begins Schwan: My name is John Schwan, I have the pleasure of interviewing Lieutenant General Everett Pratt, he and I both served in Vietnam and his career is what we're going to discuss, and I'd like to start with the simple stuff. Everett where were you born? Pratt: I was born in a little town in Georgia outside of Atlanta called Covington. And grew up there. Schwan: And at some point, you made a determination after Emory to join the [US] Air Force, I'd really like to understand that story. Pratt: Okay, let's go back a little bit, I didn't have much military connection when I was growing up. My uncle George served in WWII, he was in the Air Force in England went in on D- Day +2, as with many of the WWII vets, he never talked about it when he came back. My father -- who was of military age -- when he was sixteen, he was working in a saw mill. He was working a ripsaw, and the ripsaw caught him here and pulled from here back, so he only had these two fingers in his right hand. So he was 4F; he was not physically able to serve. I think that upset him some because he'd tell stories back during the war, he was a businessman and he'd be on trains going places. People would holler at him, throw things at him, and son of a bitch how come you're not serving? Well, he didn't say that.