Arxiv:1903.10091V1 [Physics.Ao-Ph] 25 Mar 2019 Izontal Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

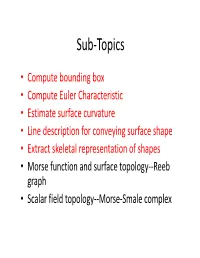

Surface Topology and Reeb Graph

Sub-Topics • Compute bounding box • Compute Euler Characteristic • Estimate surface curvature • Line description for conveying surface shape • Extract skeletal representation of shapes • Morse function and surface topology--Reeb graph • Scalar field topology--Morse-Smale complex Surface Topology – Reeb Graph What is Topology? • Topology studies the connectedness of spaces • For us: how shapes/surfaces are connected What is Topology • The study of property of a shape that does not change under deformation – Rules of deformation • 1-1 and onto • Bicontinuous (continuous both ways) • Cannot tear, join, poke or seal holes – A is homeomorphic to B Why is Topology Important? • What is the boundary of an object? • Are there holes in the object? • Is the object hollow? • If the object is transformed in some way, are the changes continuous or abrupt? • Is the object bounded , or does it extend infinitely far? Why is Topology Important? • Inherent and basic properties of a shape • We want to accurately represent and preserve these properties in different applications – Surface reconstruction – Morphing – Texturing – Simplification – Compression Image source: http://www.utdallas.edu/~xxg06 1000/physicsmorphing.htm Topology-Basic Concepts • n-manifold – Set of points – Each point has a neighborhood homeomorphic to an open set of – An n-manifold is a topological space that “locally looks like” the Euclidian space Topology-Basic Concepts • Holes/genus – Genus of a surface is the maximal number of nonintersecting simple closed curves that can be cut on the surface without disconnecting it. • Boundaries Topology-Basic Concepts • Euler’s characteristic function – • #vertices, #edges, #faces – is independent of the polygonization – Specifically, 2 2 • What are c, g, and h? χ = 2 χ = 0 Topology-Basic Concepts • Orientability – Any surface has a triangulation – Orient all triangles CW or CCW – Orientability : any two triangles sharing an edge have opposite directions on that edge. -

Approximation of Metric Spaces by Reeb Graphs: Cycle Rank of A

Filomat xx (yyyy), zzz–zzz Published by Faculty of Sciences and Mathematics, DOI (will be added later) University of Niˇs, Serbia Available at: http://www.pmf.ni.ac.rs/filomat Approximation of Metric Spaces by Reeb Graphs: Cycle Rank of a Reeb Graph, the Co-rank of the Fundamental Group, and Large Components of Level Sets on Riemannian Manifolds Irina Gelbukh CIC, Instituto Polit´ecnico Nacional, 07738, Mexico City, Mexico Abstract. For a connected locally path-connected topological space X and a continuous function f on it such that its Reeb graph R f is a finite topological graph, we show that the cycle rank of R f , i.e., the first Betti number b1(R f ), in computational geometry called number of loops, is bounded from above by the co-rank of the fundamental group π1(X), the condition of local path-connectedness being important since generally b1(R f ) can even exceed b1(X). We give some practical methods for calculating the co-rank of π1(X) and a closely related value, the isotropy index. We apply our bound to improve upper bounds on the distortion of the Reeb quotient map, and thus on the Gromov-Hausdorff approximation of the space by Reeb graphs, for the distance function on a compact geodesic space and for a simple Morse function on a closed Riemannian manifold. This distortion is bounded from below by what we call the Reeb width b(M) of a metric space M, which guarantees that any real-valued continuous function on M has large enough contour (connected component of a level set). -

The Reeb Graph Edit Distance Is Universal

The Reeb Graph Edit Distance Is Universal Ulrich Bauer Department of Mathematics, Technical University of Munich (TUM), Germany [email protected] Claudia Landi Dipartimento di Scienze e Metodi dell’Ingegneria, Università degli Studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy [email protected] Facundo Mémoli Department of Mathematics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA [email protected] Abstract We consider the setting of Reeb graphs of piecewise linear functions and study distances between them that are stable, meaning that functions which are similar in the supremum norm ought to have similar Reeb graphs. We define an edit distance for Reeb graphs and prove that it is stable and universal, meaning that it provides an upper bound to any other stable distance. In contrast, via a specific construction, we show that the interleaving distance and the functional distortion distance on Reeb graphs are not universal. 2012 ACM Subject Classification Theory of computation → Computational geometry; Mathematics of computing → Algebraic topology Keywords and phrases Reeb graphs, topological descriptors, edit distance, interleaving distance Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.SoCG.2020.15 Funding This research has been partially supported by FAR 2014 (UniMORE), ARCES (University of Bologna), and the DFG Collaborative Research Center SFB/TRR 109 “Discretization in Geometry and Dynamics”. Acknowledgements We thank Barbara Di Fabio and Yusu Wang for valuable discussions. 1 Introduction The concept of a Reeb graph of a Morse function first appeared in [13] and has subsequently been applied to problems in shape analysis in [14, 10]. The literature on Reeb graphs in the computational geometry and computational topology is ever growing (see, e.g., [2, 3] for a discussion and references). -

Rapid Mixing and Exchange of Deep-Ocean Waters in an Abyssal Boundary Current

Rapid mixing and exchange of deep-ocean waters in an abyssal boundary current Alberto C. Naveira Garabatoa,1, Eleanor E. Frajka-Williamsb, Carl P. Spingysa, Sonya Leggc, Kurt L. Polzind, Alexander Forryana, E. Povl Abrahamsene, Christian E. Buckinghame, Stephen M. Griffiesc, Stephen D. McPhailb, Keith W. Nichollse, Leif N. Thomasf, and Michael P. Meredithe aOcean and Earth Science, National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton, SO14 3ZH Southampton, United Kingdom; bNational Oceanography Centre, SO14 3ZH Southampton, United Kingdom; cNational Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory & Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Program, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544; dDepartment of Physical Oceanography, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543; ePolar Oceans, British Antarctic Survey, CB3 0ET Cambridge, United Kingdom; and fDepartment of Earth System Science, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 Edited by Eric Guilyardi, Laboratoire d’Océanographie et du Climat: Expérimentations et Approches Numériques, Institute Pierre Simon Laplace, Paris, France, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jean Jouzel May 26, 2019 (received for review March 8, 2019) The overturning circulation of the global ocean is critically shaped UK–US Dynamics of the Orkney Passage Outflow (DynOPO) by deep-ocean mixing, which transforms cold waters sinking at high project (17), and consisted of two core elements: a series of fifteen latitudes into warmer, shallower waters. The effectiveness of mixing 6- to 128-km-long vessel-based sections of profile measurements in driving this transformation is jointly set by two factors: the crossing the boundary current at an unusually high horizontal – – ∼ intensity of turbulence near topography and the rate at which well- resolution (Fig. -

Chapter 2 Approximate Thermodynamics

Chapter 2 Approximate Thermodynamics 2.1 Atmosphere Various texts (Byers 1965, Wallace and Hobbs 2006) provide elementary treatments of at- mospheric thermodynamics, while Iribarne and Godson (1981) and Emanuel (1994) present more advanced treatments. We provide only an approximate treatment which is accept- able for idealized calculations, but must be replaced by a more accurate representation if quantitative comparisons with the real world are desired. 2.1.1 Dry entropy In an atmosphere without moisture the ideal gas law for dry air is p = R T (2.1) ρ d where p is the pressure, ρ is the air density, T is the absolute temperature, and Rd = R/md, R being the universal gas constant and md the molecular weight of dry air. If moisture is present there are minor modications to this equation, which we ignore here. The dry entropy per unit mass of air is sd = Cp ln(T/TR) − Rd ln(p/pR) (2.2) where Cp is the mass (not molar) specic heat of dry air at constant pressure, TR is a constant reference temperature (say 300 K), and pR is a constant reference pressure (say 1000 hPa). Recall that the specic heats at constant pressure and volume (Cv) are related to the gas constant by Cp − Cv = Rd. (2.3) A variable related to the dry entropy is the potential temperature θ, which is dened Rd/Cp θ = TR exp(sd/Cp) = T (pR/p) . (2.4) The potential temperature is the temperature air would have if it were compressed or ex- panded (without condensation of water) in a reversible adiabatic fashion to the reference pressure pR. -

Hydrographic Atlas of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) Volume 2: Pacific Ocean

Hydrographic Atlas of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) Volume 2: Pacific Ocean Lynne D. Talley Series edited by Michael Sparrow, Piers Chapman and John Gould Hydrographic Atlas of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) Volume 2: Pacific Ocean Lynne D. Talley Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA. Series edited by Michael Sparrow, Piers Chapman and John Gould. Compilation funded by the US National Science Foundation, Ocean Science division grant OCE-9712209. Publication supported by BP. Cover Picture: The photo on the front cover was kindly supplied by Akihisa Otsuki. It shows squalls in the northernmost area of the Mariana Islands and was taken on June 12, 1993. Cover design: Signature Design in association with the atlas editors, Principal Investigators and BP. Printed by: ATAR Roto Presse SA, Geneva,Switzerland. DVD production: ODS Business Services Limited, Swindon, UK. Published by: National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, UK. Recommended form of citation: 1. For this volume: Talley, L. D., Hydrographic Atlas of the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE). Volume 2: Pacific Ocean (eds. M. Sparrow, P. Chapman and J. Gould), International WOCE Project Office, Southampton, UK, ISBN 0-904175-54-5. 2007 2. For the whole series: Sparrow, M., P. Chapman, J. Gould (eds.), The World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE) Hydrographic Atlas Series (4 vol- umes), International WOCE Project Office, Southampton, UK, 2005-2007 WOCE is a project of the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) which is sponsored by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO. -

Gibbs Seawater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox of TEOS–10

Gibbs SeaWater (GSW) Oceanographic Toolbox of TEOS–10 documentation set density and enthalpy, based on the 48-term expression for density, gsw_front_page front page to the GSW Oceanographic Toolbox The functions in this group ending in “_CT” may also be called without “_CT”. gsw_contents contents of the GSW Oceanographic Toolbox gsw_check_functions checks that all the GSW functions work correctly gsw_rho_CT in-situ density, and potential density gsw_demo demonstrates many GSW functions and features gsw_alpha_CT thermal expansion coefficient with respect to CT gsw_beta_CT saline contraction coefficient at constant CT Practical Salinity (SP), PSS-78 gsw_rho_alpha_beta_CT in-situ density, thermal expansion & saline contraction coefficients gsw_specvol_CT specific volume gsw_SP_from_C Practical Salinity from conductivity, C (incl. for SP < 2) gsw_specvol_anom_CT specific volume anomaly gsw_C_from_SP conductivity, C, from Practical Salinity (incl. for SP < 2) gsw_sigma0_CT sigma0 from CT with reference pressure of 0 dbar gsw_SP_from_R Practical Salinity from conductivity ratio, R (incl. for SP < 2) gsw_sigma1_CT sigma1 from CT with reference pressure of 1000 dbar gsw_R_from_SP conductivity ratio, R, from Practical Salinity (incl. for SP < 2) gsw_sigma2_CT sigma2 from CT with reference pressure of 2000 dbar gsw_SP_salinometer Practical Salinity from a laboratory salinometer (incl. for SP < 2) gsw_sigma3_CT sigma3 from CT with reference pressure of 3000 dbar gsw_sigma4_CT sigma4 from CT with reference pressure of 4000 dbar Absolute Salinity -

Realizable Piecewise Linear Paths of Persistence Diagrams with Reeb Graphs

Realizable piecewise linear paths of persistence diagrams with Reeb graphs Rehab Alharbi1, Erin Wolf Chambers2, and Elizabeth Munch2 1Dept of Mathematics & Statistics, Saint Louis University 2Dept of Computer Science, Saint Louis University 3Dept of Computational Mathematics, Science & Engineering, Dept of Mathematics, Michigan State University Abstract Reeb graphs are widely used in a range of fields for the purposes of analyzing and com- paring complex spaces via a simpler combinatorial object. Further, they are closely related to extended persistence diagrams, which largely but not completely encode the information of the Reeb graph. In this paper, we investigate the effect on the persistence diagram of a particular continuous operation on Reeb graphs; namely the (truncated) smoothing operation. This con- struction arises in the context of the Reeb graph interleaving distance, but separately from that viewpoint provides a simplification of the Reeb graph which continuously shrinks small loops. We then use this characterization to initiate the study of inverse problems for Reeb graphs using smoothing by showing which paths in persistence diagram space (commonly known as vineyards) can be realized by a path in the space of Reeb graphs via these simple operations. This allows us to solve the inverse problem on a certain family of piecewise linear vineyards when fixing an initial Reeb graph. 1 Introduction Reeb graphs have become an important tool in topological data analysis for the purpose of visualiz- ing continuous functions on complex spaces, as they yield a simplified discrete structure. Originally developed in relation to Morse theory [29], these objects are used extensively for shape comparison, constructing skeletons of data sets, surface simplification, and visualization; for more details on arXiv:2107.04654v1 [cs.CG] 9 Jul 2021 these and more applications, we refer to recent surveys on the topic [5, 31]. -

Spiciness Theory Revisited, with New Views on Neutral Density, Orthogonality, and Passiveness

Ocean Sci., 17, 203–219, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/os-17-203-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Spiciness theory revisited, with new views on neutral density, orthogonality, and passiveness Rémi Tailleux Dept. of Meteorology, University of Reading, Earley Gate, RG6 6ET Reading, United Kingdom Correspondence: Rémi Tailleux ([email protected]) Received: 26 April 2020 – Discussion started: 20 May 2020 Revised: 8 December 2020 – Accepted: 9 December 2020 – Published: 28 January 2021 Abstract. This paper clarifies the theoretical basis for con- 1 Introduction structing spiciness variables optimal for characterising ocean water masses. Three essential ingredients are identified: (1) a As is well known, three independent variables are needed to material density variable γ that is as neutral as feasible, (2) a fully characterise the thermodynamic state of a fluid parcel in material state function ξ independent of γ but otherwise ar- the standard approximation of seawater as a binary fluid. The bitrary, and (3) an empirically determined reference function standard description usually relies on the use of a tempera- ξr(γ / of γ representing the imagined behaviour of ξ in a ture variable (such as potential temperature θ, in situ temper- notional spiceless ocean. Ingredient (1) is required because ature T , or Conservative Temperature 2), a salinity variable contrary to what is often assumed, it is not the properties im- (such as reference composition salinity S or Absolute Salin- posed on ξ (such as orthogonality) that determine its dynam- ity SA), and pressure p. -

Equations of Motion Using Thermodynamic Coordinates

2814 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 30 Equations of Motion Using Thermodynamic Coordinates ROLAND A. DE SZOEKE College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon (Manuscript received 21 October 1998, in ®nal form 30 December 1999) ABSTRACT The forms of the primitive equations of motion and continuity are obtained when an arbitrary thermodynamic state variableÐrestricted only to be vertically monotonicÐis used as the vertical coordinate. Natural general- izations of the Montgomery and Exner functions suggest themselves. For a multicomponent ¯uid like seawater the dependence of the coordinate on salinity, coupled with the thermobaric effect, generates contributions to the momentum balance from the salinity gradient, multiplied by a thermodynamic coef®cient that can be com- pletely described given the coordinate variable and the equation of state. In the vorticity balance this term produces a contribution identi®ed with the baroclinicity vector. Only when the coordinate variable is a function only of pressure and in situ speci®c volume does the coef®cient of salinity gradient vanish and the baroclinicity vector disappear. This coef®cient is explicitly calculated and displayed for potential speci®c volume as thermodynamic coor- dinate, and for patched potential speci®c volume, where different reference pressures are used in various pressure subranges. Except within a few hundred decibars of the reference pressures, the salinity-gradient coef®cient is not negligible and ought to be taken into account in ocean circulation models. 1. Introduction perature surfaces is a potential for the acceleration ®eld, Potential temperature, the temperature a ¯uid parcel when friction is negligible. Because the gradient of this would have if removed adiabatically and reversibly from function gives the geostrophic ¯ow when it balances ambient pressure to a reference pressure, is a valuable Coriolis force, it is also called the geostrophic stream- concept in the study of the atmosphere and oceans. -

Recovery of Temperature, Salinity, and Potential Density from Ocean

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Recovery of temperature, salinity, and potential density from 10.1002/2013JC009662 ocean reflectivity Key Points: Berta Biescas1,2, Barry R. Ruddick1, Mladen R. Nedimovic3,4,5, Valentı Sallare`s2, Guillermo Bornstein2, Recovery of oceanic T, S, and and Jhon F. Mojica2 potential density from acoustic reflectivity data 1Department of Oceanography, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2Department of Marine Geology, Thermal anomalies observations at 3 the Mediterranean tongue level Institut de Cie`ncies del Mar ICM-CSIC, Barcelona, Spain, Department of Earth’s Sciences, Dalhousie University, Halifax, 4 5 Comparison between acoustic Nova Scotia, Canada, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York, USA, University of reflectors in the ocean and isopycnals Texas Institute for Geophysics, Austin, Texas, USA Supporting Information: Methods Abstract This work explores a method to recover temperature, salinity, and potential density of the Supporting figures ocean using acoustic reflectivity data and time and space coincident expendable bathythermographs (XBT). The acoustically derived (vertical frequency >10 Hz) and the XBT-derived (vertical frequency <10 Hz) impe- Correspondence to: dances are summed in the time domain to form impedance profiles. Temperature (T) and salinity (S) are B. Biescas, then calculated from impedance using the international thermodynamics equations of seawater (GSW [email protected] TEOS-10) and an empirical T-S relation derived with neural networks; and finally potential density (q) is cal- culated from T and S. The main difference between this method and previous inversion works done from Citation: Biescas, B., B. R. Ruddick, M. R. real multichannel seismic reflection (MCS) data recorded in the ocean, is that it inverts density and it does Nedimovic, V. -

Thermodynamic Tree: the Space of Admissible Paths † Alexander N

SIAM J. APPLIED DYNAMICAL SYSTEMS c 2013 Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 246–278 ∗ Thermodynamic Tree: The Space of Admissible Paths † Alexander N. Gorban Abstract. Is a spontaneous transition from a state x to a state y allowed by thermodynamics? Such a question arises often in chemical thermodynamics and kinetics. We ask the following more formal question: Is there a continuous path between these states, along which the conservation laws hold, the concentra- tions remain nonnegative, and the relevant thermodynamic potential G (Gibbs energy, for example) monotonically decreases? The obvious necessary condition, G(x) ≥ G(y), is not sufficient, and we construct the necessary and sufficient conditions. For example, it is impossible to overstep the equi- − librium in 1-dimensional (1D) systems (with n components and n 1 conservation laws). The system cannot come from a state x to a state y if they are on the opposite sides of the equilibrium even if G(x) >G(y). We find the general multidimensional analogue of this 1D rule and constructively solve the problem of the thermodynamically admissible transitions. We study dynamical systems, which are given in a positively invariant convex polyhedron D and have a convex Lyapunov function G. An admissible path is a continuous curve in D along which G does not increase. For x, y ∈ D, x y (x precedes y) if there exists an admissible path from x to y and x ∼ y if x y and y x. ThetreeofG in D is a quotient space D/ ∼ . We provide an algorithm for the construction of this tree.