Studies. Cultural Landscape and the Renovation of Teaching in US Schools of Architecture Between the 50S and the 70S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Cities: 75 Years of Planning Better Futures at MIT / Lawrence J

Changing Cities 75 Years of Planning Better Futures at MIT Lawrence J. Vale © 2008 by Lawrence J. Vale and the SA+P Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. Vale, Lawrence J. Changing Cities: 75 Years of Planning Better Futures at MIT / Lawrence J. Vale. ISBN 978-0-9794774-2-3 Published in the United States by SA+P Press. Support for this catalogue and its related exhibition was provided by the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and the Wolk Gallery, School of Architecture + Planning. Developed from an exhibition at the Wolk Gallery, MIT School of Architecture + Planning, February 12 - April 11, 2008. Exhibition curated and written by Lawrence J. Vale, in collaboration with Gary Van Zante, Laura Knott and Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani/ Buscada Design. Exhibition & Catalogue design: Buscada Design SA PMITDUSP SCHOOL OFMIT ARCHITECTURE + PLANNING Dedicated to the Students and Alumni/ae of MIT’s Course in City Planning Contents 2 Acknowledgments 4 Preface 12 Planning at MIT: An Introduction 14 Up from Adams 25 The Burdell Committee & The Doctoral Program 28 The Joint Center 31 Ciudad Guayana 35 City Image & City Design: The Lynchian Tradition 41 Planning, The Revolution 47 Planning in Communities 50 Affordable Housing 58 Environmental Policy & Planning 62 The Laboratory of Architecture & Planning 65 The Center for Real Estate 68 International Development 74 Practica 78 DUSP in New Orleans 81 DUSP in China 85 Technologies & Cities 88 Changing Cities: Is there a DUSP way? 90 A Growing Department 92 An Urbanized and Urbanizing Planet 94 Appendix I: Here We Go Again: Recurring Questions Facing DUSP 107 Appendix II: Trends in Cities, Planning, and Development 121 Appendix III: “Tomorrow the Universe” 130 Notes 133 Images Acknowledgments Work on this exhibition and catalogue began in 2004, and I am particularly grateful to Diana Sherman (MCP ‘05) and Alison Novak (MCP ‘06) for their initial assistance with archival examination. -

Canadian Planning Through a Transnational Lens: the Evolution of Urban Planning in Canada, 1890-1930

Canadian Planning through a Transnational Lens: the Evolution of Urban Planning in Canada, 1890-1930 Catherine Mary Ulmer A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Fall 08 April 2017 Department of History and Classical Studies, Faculty of Arts, McGill University, Montreal © Catherine Mary Ulmer ii Abstract From the late nineteenth century onwards, a varied group of middle and upper class English- Canadians embraced urban planning, forming connections with the international planning cohort and circulating planning knowledge across Canada. Yet, despite their membership within the wider planning world, and the importance of such involvement to Canada’s early planning movement, the current historical narrative does not fully account for the complex nature of Canadian interactions with this wider planning cohort. This dissertation points to the necessity of applying a transnational perspective to our understanding of Canada’s modern planning history. It considers the importance of English-Canadian urban planning networking from 1910–1914, argues that these individuals were knowledgeable and selective borrowers of foreign planning information, and reassesses the role of Thomas Adams, the British expert who acted as a national planning advisor to Canada (1915–1922) and has been credited with founding Canada’s planning movement. Reevaluating his position, I argue that Adams did not introduce Canadians to modern planning. Instead his central role came through his efforts to help professionalize planning through creating the Town Planning Institute of Canada (TPIC) in 1919. As I assert, by restricting full membership to male professionals the TPIC relegated amateur planning advocates to a supporting role, devaluing the contributions of non-professionals, and, in particular, women. -

Computing Environmental Design1

3 COMPUTING ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN1 Peder Anker ‘[S] urvival of mankind as we know it’ is at stake, and the ‘natural human ecology stands in jeopardy’. Serge Chermayeff’s plea for environmental conservation addressed the growing use of cars, as he thought everyone’s access to them resulted in a noisy ‘auto- anarchy’ with roads depredating the natural environment. ‘Personally, I observe these probabilities with profoundest melancholy’ in Cape Cod, he noted (Chermayeff 1960, 190, 193). The things affected by this predicament ranged from the privacy of his cottage, to the ecology of the neighbourhood, the social order of the Wellfleet community, and even the planning of the entire peninsula. Only a powerful computer could solve the complexity of the problem, Chermayeff thought. Through the lens of social history of design, I argue that the early history of computing in design established a managerial view of the natural world reflecting the interests of the well- educated, liberal elite. Chermayeff was part of a group of modernist designers with vacation homes on Cape Cod who nurtured political ties to the Kennedy family. Their community was fashioned around using the Wellfleet environment as a place for leisure and vacation, a lifestyle threatened by various local housing and road developments. In response they began promoting a national park to protect the area, and began pondering on finding new tools for proper environ- mental design that could protect their interests. The computer became their unifying tool for a multilayered approach to environmental planning, which saw nature as rational in character. It offered managerial distance and an imagined socio- political objectivity. -

Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring Americaâ•Žs New •Œmegapolitanâ•Š Geography

Brookings Mountain West Publications Publications (BMW) 2005 Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Brookings Mountain West, [email protected] Dawn Dhavale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs Part of the Urban Studies Commons Repository Citation Lang, R. E., Dhavale, D. (2005). Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography. 1-33. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/brookings_pubs/38 This Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Report has been accepted for inclusion in Brookings Mountain West Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. METROPOLITAN INSTITUTE CENSUS REPORT SERIES Census Report 05:01 (May 2005) Beyond Megalopolis: Exploring America’s New “Megapolitan” Geography Robert E. Lang Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech Dawn Dhavale Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech “... the ten Main Findings and Observations Megapolitans • The Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech identifi es ten US “Megapolitan have a Areas”— clustered networks of metropolitan areas that exceed 10 million population total residents (or will pass that mark by 2040). equal to • Six Megapolitan Areas lie in the eastern half of the United States, while four more are found in the West. -

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden. Dean Cardasis, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, University of Massachusetts (Amherst) “To see the universe within a place is to see a garden; approach to American garden design. to see it so is to have a garden; Rose was a rugged individualist who explored the not to prevent its happening is to build a garden.” universal through the personal. Both his incisive James Rose, Modern American Gardens. writings and his exquisite gardens evidence the vitality of an approach to garden making (and life) as James Rose was one of the leaders of the modern an adventure within the great cosmic joke. He movement in American garden design. I write this disapproved of preconceiving design or employing advisedly because James “ the-maverick-impossible” any formulaic method, and favored direct Rose would be the first to disclaim it. “I’m no spontaneous improvisation with nature. Unlike fellow missionary,” he often exclaimed, “I do what pleases modern rebels and friends, Dan Kiley and Garrett me!”1 Nevertheless, Rose, through his experimental Eckbo, Rose devoted his life to exploring the private built works, his imaginative creative writing, and his garden as a place of self-discovery. Because of the generally subversive life-style provides perhaps the contemplative nature of his gardens, his work has clearest image of what may be termed a truly modern sometimes been mislabeled Japanesebut nothing made Rose madder than to suggest he did Japanese gardens. In fact, in response to a query from one prospective client as to whether he could do a Japanese garden for her, Rose replied, “Of course, whereabouts in Japan do you live?”2 This kind of response to what he would call his clients’ “mind fixes” was characteristic of James Rose. -

Thomas Adams, 1871 - 1940

Thomas Adams, 1871 - 1940 by David Lewis Stein David Lewis Stein is a TORONTO STAR urban affairs columnist. It may be some comfort to remember that Thomas Adams, the godfather of Canadian planning, was an international figure who suffered because of the public mood swings that still affect the planning profession today. Adams was born in 1871 on a dairy farm just outside of Edinburgh, Scotland, and in his early twenties he even operated a farm himself. From these agrarian roots, he went on to become a founding member of the British Town Planning Institute, founder of the Town Planning Institute of Canada and a founding member of the American City Planning Institute, forerunner of the American Institute of Planners. Adams accomplished this institutional hat-trick -- as well as becoming one of the most important early private practitioners--not so much because of the originality of his ideas but because he was an active, vigorous individual who was fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time. While a farmer on the outskirts of Edinburgh at the end of the last century, Adams became a local councillor. He later moved to London to pursue a career in journalism and got caught up in the excitement of the Garden City movement. He qualified as a surveyor and became the first person in England to make his living entirely from planning and designing garden suburbs--doing no less than seven of them. By 1910, Adams was so widely recognized in his new profession that he became the first president of the British Town Planning Institute. -

Pieris, A. Sociospatial Genealogies of Wartime Impoverishment

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND VOL. 33 Edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad Published in Melbourne, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2016 ISBN: 978-0-7340-5265-0 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Anoma Pieris “Sociospatial Genealogies of Wartime Impoverishment: Temporary Farm Labour Camps in the U.S.A.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad, 558-567. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Anoma Pieris University of Melbourne SOCIOSPATIAL GENEALOGIES OF WARTIME IMPOVERISHMENT: TEMPORARY FARM LABOUR CAMPS IN THE U.S.A. Established to develop New Deal resettlement programs in 1937, the United States Farm Security Administration (F.S.A.) was best known for accommodating migratory labour from the drought-stricken central plains. Large numbers arriving in California prompted F.S.A. engineers and architects to develop purpose-designed labour camps and townships, described as early exemplars of community planning. Yet in 1942, when 118,803 Japanese and Japanese Americans were evacuated from the newly created Military Exclusion Zones and incarcerated in relocation centres, F.S.A. skills were put to a different use. This paper demonstrates how wartime exigency, racist immigration policies and militarisation transformed a model for relief and rehabilitation into a carceral equivalent. It contextualises this transformation within a socio-spatial genealogy of temporary facilities that accommodated mass human displacements – including two examples from California: the Tulare County F.S.A. -

Evolution of Canadian Planning PASSÉ L’Évolution De L’Urbanisme Canadien

PAST Evolution of Canadian Planning PASSÉ L’évolution de l’urbanisme canadien CLICK TO RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS Our common past? Notre passé commun ? A re-interpretation Une réinterprétation des of Canadian planning histories histoires de l’urbanisme au Canada By Jeanne M. Wolfe, David L.A. Gordon, and Raphaël Fischler Par Jeanne M. Wolfe, David L.A. Gordon et Raphaël Fischler lanning is about change, and the common belief of all e premier enjeu de l’urbanisme est le changement et planners, no matter their specialty, expertise, skill, or area of tous les urbanistes, quels que soient leur spécialité, leur endeavour, is that change can be managed for the betterment expertise, leurs compétences ou leur domaine d’activité, ont of the community. Planners argue endlessly about the public pour principe commun que le changement peut être géré good – who is the public and what is good – but all share pour le bien de la collectivité. Les urbanistes débattent sans Pthe sentiment that the human environment can be improved in some Lcesse du bien public – qui est le public et ce qui est bon – mais way. This article traces the evolution of the profession of planning, its tous partagent le sentiment que l’environnement humain peut institutions, activities, underpinnings, and recurring debates. It follows être amélioré d’une manière ou d’une autre. Cet essai retrace a chronological order, mirroring the major social currents of the times l’évolution de la profession d’urbaniste, de ses institutions, de ses from first Indigenous settlements, while concentrating mainly on the activités, de ses fondements et de ses débats récurrents. -

Bodies and Nature in International Garden City Movement Planning, 1898-1937

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: ACTS OF LIVELIHOOD: BODIES AND NATURE IN INTERNATIONAL GARDEN CITY MOVEMENT PLANNING, 1898-1937 Samuel M. Clevenger Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor David L. Andrews Department of Kinesiology Urban planning and reform scholars and policymakers continue to cite the “garden city” community model as a potential blueprint for planning environmentally sustainable, economically equitable, humane built environments. Articulated by the British social reformer Sir Ebenezer Howard and his 1898 book To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, the model represented a method for uniting the benefits of town and country through a singular, pre-planned, “healthy” community, balancing spaces of “countryside” and “nature” with affordable, well-built housing and plentiful cultural attractions associated with city life. The book catalyzed an early twentieth-century international movement for the promotion and construction of garden cities. Howard’s garden city remains a highly influential context in the history of town planning and urban public health reform, as well as more recent environmentally-friendly urban design movements. To date, while historians have long examined the garden city as an agent of social and spatial reform, little analysis has been devoted to the role of prescribed embodiment and deemed “healthy” physical cultural forms and practices in the promotion and construction of garden cities as planned communities for “healthy living.” Informed by recent scholarship in Physical Cultural Studies (PCS), embodied environmental history, cultural materialism, and theories of modern biopower, this dissertation studies the cultural history of international garden city movement planning in early twentieth century Britain and the United States. -

Feb 2 7 2004 Libraries Rotch

Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joso Magalhses Rocha Licenciatura in Architecture FAUTL, Lisbon (1992) M.Sc. in Advanced Architectural Design The Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation Columbia University, New York. USA (1995) Submitted to the Department of Architecture, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY OF TECHNOLOGY February 2004 FEB 2 7 2004 @2004 Altino Joso Magalhaes Rocha All rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author......... Department of Architecture January 9, 2004 Ce rtifie d by ........................................ .... .... ..... ... William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture ana Media Arts and Sciences Thesis Supervisor 0% A A Accepted by................................... .Stanford Anderson Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students Head, Department of Architecture ROTCH Doctoral Committee William J. Mitchell Professor of Architecture and Media Arts and Sciences George Stiny Professor of Design and Computation Michael Hays Eliot Noyes Professor of Architectural Theory at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design Architecture Theory 1960-1980. Emergence of a Computational Perspective by Altino Joao de Magalhaes Rocha Submitted to the Department of Architecture on January 9, 2004 in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: Design and Computation Abstract This thesis attempts to clarify the need for an appreciation of architecture theory within a computational architectural domain. It reveals and reflects upon some of the cultural, historical and technological contexts that influenced the emergence of a computational practice in architecture. -

From the Garden

From The Garden Lawrence Halprin and the Modern Landscape Marc Treib AN INTRODUCTION As a landscape architect, urban designer, author, and study the design of The Sea Ranch in northern Califor- proselytizer for the fi eld’s recognition, Lawrence Hal- nia—one of the fi rst planned communities to carefully prin cast a giant shadow (Figure 1). His practice, which inventory the existing vegetation, hydrology, topog- spanned half a century, was so multi-faceted that to raphy, and fauna and use these factors as the basis for date nothing written about him has satisfactorily design.2 Collectively these landscapes demonstrate that covered the broad range of his contributions. In the last Halprin’s thinking, as represented in his designs and decade, however, there has been renewed interest in his his writings, was impressively comprehensive. early attempts to record movement; others have tried Only with slight exaggeration could we say that to assess the nature of the collaboration with his wife, Halprin is generally known as a landscape architect the dancer Anna Halprin; others still have attempted who worked primarily in the urban sphere, designing to adopt his RSVP Cycles as a design method.1 Sadly, fountains and plazas—including one major memo- of late Halprin’s several major works have been threat- rial—within cities from coast to coast, and even ened, some have been demolished or bowdlerized, and abroad. Yet, as Garrett Eckbo once claimed, it is the much of the renewed interest in the Halprin landscape garden that provides the classroom and test site for has been a byproduct of eff orts to preserve major landscape architects.3 There, one learns a vocabu- projects such as Manhattan Square Park in Rochester, lary with which one designs, the processes by which Freeway Park in Seattle, and Heritage Square in Fort landscapes are realized, the people who realize them, Worth. -

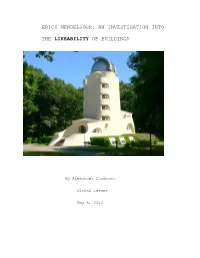

Erich Mendelsohn: an Investigation Into

ERICH MENDELSOHN: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE LIKEABILITY OF BUILDINGS By Alexander Luckmann Global Issues May 6, 2013 Abstract In my paper, I attempted to answer a central questions about architecture: what makes certain buildings create such a strong sense of belonging and what makes others so sterile and unwelcoming. I used the work of German-born architect Erich Mendelsohn to help articulate solutions to these questions, and to propose paths of exploration for a kinder and more place-specific architecture, by analyzing the success of many of Mendelsohn’s buildings both in relation to their context and in relation to their emotional effect on the viewer/user, and by comparing this success with his less successful buildings. I compared his early masterpiece, the Einstein Tower, with a late work, the Emanue-El Community Center, to investigate this difference. I attempted to place Mendelsohn in his architectural context. I was sitting on the roof of the apartment of a friend of my mother’s in Constance, Germany, a large town or a small city, depending on one’s reference point. The apartment, where I had been frequently up until perhaps the age of six but hadn’t visited recently, is on the top floor of an old building in the city center, dating from perhaps the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries. The rooms are fairly small, but they are filled with light, and look out over the bustling downtown streets onto other quite similar buildings. Almost all these buildings have stores on the ground floor, often masking their beauty to those who don’t look up (whatever one may say about modern stores, especially chain stores, they have done a remarkable job of uglifying the street at ground level).