From the Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Topics in Modern Architecture in Southern California

TOPICS IN MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA ARCH 404: 3 units, Spring 2019 Watt 212: Tuesdays 3 to 5:50 Instructor: Ken Breisch: [email protected] Office Hours: Watt 326, Tuesdays: 1:30-2:30; or to be arranged There are few regions in the world where it is more exciting to explore the scope of twentieth-century architecture than in Southern California. It is here that European and Asian influences combined with the local environment, culture, politics and vernacular traditions to create an entirely new vocabulary of regional architecture and urban form. Lecture topics range from the stylistic influences of the Arts and Crafts Movement and European Modernism to the impact on architecture and planning of the automobile, World War II, or the USC School of Architecture during the 1950s. REQUIRED READING: Thomas S., Hines, Architecture of the Sun: Los Angeles Modernism, 1900-1970, Rizzoli: New York, 2010. You can buy this on-line at a considerable discount. Readings in Blackboard and online. Weekly reading assignments are listed in the lecture schedule in this syllabus. These readings should be completed before the lecture under which they are listed. RECOMMENDED OPTIONAL READING: Reyner Banham, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, 1971, reprint ed., Berkeley; University of California Press, 2001. Barbara Goldstein, ed., Arts and Architecture: The Entenza Years, with an essay by Esther McCoy, 1990, reprint ed., Santa Monica, Hennessey and Ingalls, 1998. Esther McCoy, Five California Architects, 1960, reprint ed., New York: -

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-Of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1

CATALOG NO. 1 Artists’ Ephemera, Exhibition Documents and Rare and Out-of-Print Books on Art, Architecture, Counter-Culture and Design 1. IMAGE BANK PENCILS Vancouver Canada Circa 1970. Embossed Pencils, one red and one blue. 7.5 x .25” diameter (19 x 6.4 cm). Fine, unused and unsharpened. $200 Influenced by their correspondence with Ray Johnson, Michael Morris and Vincent Trasov co- founded Image Bank in 1969 in Vancouver, Canada. Paralleling the rise of mail art, Image Bank was a collaborative, postal-based exchange system between artists; activities included requests lists that were published in FILE Magazine, along with publications and documents which directed the exchange of images, information, and ideas. The aim of Image Bank was an inherently anti- capitalistic collective for creative conscious. 2. AUGUSTO DE CAMPOS: CIDADE=CITY=CITÉ Edinburgh Scotland 1963/1964. Concrete Poem, letterpressed. 20 x 8” (50.8 x 20.3 cm) when unfolded. Very Good, folded as issued, some toning at edges, very slight soft creasing at folds and edges. $225. An early concrete poetry work by Augusto de Campos and published by Ian Hamilton Finlay’s Wild Hawthorn Press. Campos is credited as a co-founder (along with his brother Haroldo) of the concrete poetry movement in Brazil. His work with the poem Cidade=City=Cité spanned many years, and included various manifestations: in print (1960s), plurivocal readings and performances (1980s-1990s), and sculpture (1987, São Paulo Biennial). The poem contains only prefixes in the languages of Portuguese, English and French which are each added to the suxes of cidade, city and cité to form trios of words with the same meaning in each language. -

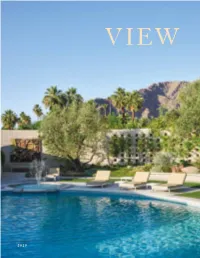

Read This Issue

VIEW 2019 VIEW from the Director’s Office Dear Friends of LALH, This year’s VIEW reflects our recent sharpening focus on California, from the Bay Area to San Diego. We open with an article by JC Miller about Robert Royston’s final project, the Harris garden in Palm Springs, which he worked on personally and continues to develop with the owners. A forthcoming LALH book on Royston by Miller and Reuben M. Rainey, the fourth volume in our Masters of Modern Landscape Design series, will be released early next year at Modernism Week in Palm Springs. Both article and book feature new photographs by the stellar landscape photographer Millicent Harvey. Next up, Kenneth I. Helphand explores Lawrence Halprin’s extraordinary drawings and their role in his de- sign process. “I find that I think most effectively graphically,” Halprin explained, and Helphand’s look at Halprin’s prolific notebook sketches and drawings vividly illuminates the creative symbiosis that led to the built works. The California theme continues with an introduction to Paul Thiene, the German-born landscape architect who super- vised the landscape development of the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego and went on to establish a thriving practice in the Southland. Next, the renowned architect Marc Appleton writes about his own Santa Barbara garden, Villa Corbeau, inspired—as were so many of Thiene’s designs—by Italy. The influence of Italy was also major in the career of Lockwood de Forest Jr. Here, Ann de Forest remembers her grandparents and their Santa Barbara home as the family archives, recently donated by LALH, are moved to the Architecture & Design Collections at UC Santa Barbara. -

Curran House Historic Structure Report This Report Commissioned by the Friends of the Curran House Committee

CURRAN HOUSE HISTORIC STRUCTURE REPORT This report commissioned by the Friends of the Curran House Committee. Published May, 2010 Cover art 2009 photograph of the Curran House, taken by Susan Johnson, Artifacts Consulting, Inc. Contributors The authors of this report wish to express our gratitude for the contribution of the following persons and entities: the Western Washington Chapter of Documentation and Conservation of the Modern Movement; Washington Department of Archaeol- ogy and Historic Preservation, particularly Michael Houser for sharing artwork and his knowledge of Robert Billsbrough Price’s work; Tacoma Public Library, Northwest Room staff; and the Friends of the Curran House, including Cindy Bonaro, Karen Benveniste, Biz Lund and Linda Tanz. 3 4 Administrative Data Name(s) Charles and Mary Louise Curran Residence (Also currently part of the Curran Apple Orchard Park, which belongs to the City of University Place) Location 4009 Curran Lane University Place, WA Pierce County parcel 0220163014 Proposed Treatment Rehabilitation Cultural Resource Data 1955, date of construction (per Pierce County Assessor) and period of significance Robert Billsbrough Price, architect Modern Style Individually eligible at the local level under criterion C for being a fine example of modernist residential design on the West Coast during the 1950’s and for exhibiting advances in building materials in the post-war era. Furthermore, the house is a unique hybrid of speculative model houses and custom design elements by Robert Billsbrough Price, Ta- coma’s leading architect of the 20th century. The house and associated apple orchard are also significant under criterion A, representing the development of University Place with semi-urban lifeways. -

Commartslectures00connrich.Pdf

of University California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Betty Connors THE COMMITTEE FOR ARTS AND LECTURES, 1945-1980: THE CONNORS YEARS With an Introduction by Ruth Felt Interviews Conducted by Marilynn Rowland in 1998 Copyright 2000 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Betty Connors dated January 28, 2001. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden. Dean Cardasis, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, University of Massachusetts (Amherst) “To see the universe within a place is to see a garden; approach to American garden design. to see it so is to have a garden; Rose was a rugged individualist who explored the not to prevent its happening is to build a garden.” universal through the personal. Both his incisive James Rose, Modern American Gardens. writings and his exquisite gardens evidence the vitality of an approach to garden making (and life) as James Rose was one of the leaders of the modern an adventure within the great cosmic joke. He movement in American garden design. I write this disapproved of preconceiving design or employing advisedly because James “ the-maverick-impossible” any formulaic method, and favored direct Rose would be the first to disclaim it. “I’m no spontaneous improvisation with nature. Unlike fellow missionary,” he often exclaimed, “I do what pleases modern rebels and friends, Dan Kiley and Garrett me!”1 Nevertheless, Rose, through his experimental Eckbo, Rose devoted his life to exploring the private built works, his imaginative creative writing, and his garden as a place of self-discovery. Because of the generally subversive life-style provides perhaps the contemplative nature of his gardens, his work has clearest image of what may be termed a truly modern sometimes been mislabeled Japanesebut nothing made Rose madder than to suggest he did Japanese gardens. In fact, in response to a query from one prospective client as to whether he could do a Japanese garden for her, Rose replied, “Of course, whereabouts in Japan do you live?”2 This kind of response to what he would call his clients’ “mind fixes” was characteristic of James Rose. -

20 09 Annual Report

20 annual report 09 the cultural landscape foundation 03 board / staff 04 letter from president 05 education 09 publications 09 exhibitions 10 outreach + events 15 supporters 17 financial exhibitions Marvels of Modernism Cover Photos: Exhibition and Opening (left) Newport Garden Excursion, March 2009 Reception at Design Within (right) TCLF Excursion at the Farnworth Pavilion in Plano, IL, September 2009 Reach, Dallas, TX contents See Page 7 2 Board / Staff Letter from the President The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF) achieved new partnerships with New York Botanical Garden, (2008) is currently on view at the Andy Warhol Museum Board of Directors Officers of the Board several major milestones in 2009, resulting in University of California Berkeley, and The Andy Warhol in Pittsburgh and Heroes of Horticulture (2007) opens significant audience growth, valuable media coverage Museum. Through these partnerships, we organized at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas Christine Astorino Ann Mullins Kurt Culbertson, Co-Chairman and attention for landscapes, landscape architecture five conferences in New York, Nashville, Berkeley, in January 2010. Amanda Graham Barton Jo Ann Nathan Shaun Saer Duncan, Co-Chairman and practitioners. Here are a few highlights: Pittsburgh, and Chicago to celebrate the publication of Carolyn Bennett Patricia O’Donnell Douglas Reed, Co-Chairman We are equally energized as we approach next year’s Sarah Boasberg Laurie Olin Shaping the American Landscape. First, we launched What’s Out There, the first-ever Sheila Brady Libby Page initiatives. Thanks in part to generous grants from Wiki-based Web site about parks, gardens, and other Laura Burnett Kalvin Platt Continuing the Pioneers of American Landscape Design the Richard H. -

Pieris, A. Sociospatial Genealogies of Wartime Impoverishment

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND VOL. 33 Edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad Published in Melbourne, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2016 ISBN: 978-0-7340-5265-0 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Anoma Pieris “Sociospatial Genealogies of Wartime Impoverishment: Temporary Farm Labour Camps in the U.S.A.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad, 558-567. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Anoma Pieris University of Melbourne SOCIOSPATIAL GENEALOGIES OF WARTIME IMPOVERISHMENT: TEMPORARY FARM LABOUR CAMPS IN THE U.S.A. Established to develop New Deal resettlement programs in 1937, the United States Farm Security Administration (F.S.A.) was best known for accommodating migratory labour from the drought-stricken central plains. Large numbers arriving in California prompted F.S.A. engineers and architects to develop purpose-designed labour camps and townships, described as early exemplars of community planning. Yet in 1942, when 118,803 Japanese and Japanese Americans were evacuated from the newly created Military Exclusion Zones and incarcerated in relocation centres, F.S.A. skills were put to a different use. This paper demonstrates how wartime exigency, racist immigration policies and militarisation transformed a model for relief and rehabilitation into a carceral equivalent. It contextualises this transformation within a socio-spatial genealogy of temporary facilities that accommodated mass human displacements – including two examples from California: the Tulare County F.S.A. -

Judson Dance Theater: the Work Is Never Done

Judson Dance Theater: The Work is Never Done Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done The Museum of Modern Art, New York September 16, 2018-February 03, 2019 MoMA, 11w53, On View, 2nd Floor, Atrium MoMA, 11w53, On View, 2nd Floor, Contemporary Galleries Gallery 0: Atrium Complete Charles Atlas video installation checklist can be found in the brochure Posters CAROL SUMMERS Poster for Elaine Summers’ Fantastic Gardens 1964 Exhibition copy 24 × 36" (61 × 91.4 cm) Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library, GIft of Elaine Summers Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for an Evening of Dance 1963 Exhibition copy Yvonne Rainer Papers, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Concert of Dance #13, Judson Memorial Church, New York (November 19– 20, 1963) 1963 11 × 8 1/2" (28 × 21.6 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Concert of Dance #5, America on Wheels, Washington, DC (May 9, 1963) 1963 8 1/2 × 11" (21.6 × 28 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Poster for Steve Paxton’s Afternoon (a forest concert), 101 Appletree Row, Berkeley Heights, New Jersey (October 6, 1963) 1963 8 1/2 × 11" (21.6 × 28 cm) Judson Memorial Church Archive, Fales Library & Special Collections, New York University Libraries Gallery 0: Atrium Posters Flyer for -

Landscape Architecture … Is a Social Art

Landscape architecture … is a social art. – Lawrence Halprin, 2003 The Landscape Architecture of Lawrence Halprin The Cultural Landscape Foundation connecting people to places™ ® tclf.org What’s Out There [cover] Roger Foley Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial 2016 C-print 36 x 24 inches [opposite] Roger Foley Fountain Detail, Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial 2016 Acknowledgements This gallery guide was created to accompany the traveling photographic exhibition The Landscape Architecture of Lawrence Halprin, which debuted at the National Building Museum on November 5, 2016. The exhibition was organized by The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), and co-curated by Charles A. Birnbaum, President & CEO, FASLA, FAAR, Nord Wennerstrom, Director of Communications, and Eleanor Cox, Project Manager, in collaboration with G. Martin Moeller, Jr., Senior Curator at the National Building Museum. The production of this guide would not have been possible without the help and support of the Halprin family, and the archivists at the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania, where Lawrence Halprin’s archive is kept. We wish to thank the site owners and administrators who graciously allowed us to document their properties, particularly Richard Grey, Diana Bonyhadi, Emma Chapman, and Anna Halprin, who allowed us access to their private residences. We also wish to thank the photographers who generously donated their time and energy to documenting these sites, and Russell Hart for proofing the photography. Finally, we are grateful to the National Building Museum’s Chase W. Rynd, Hon. ASLA, President and Executive Director of THE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE OF the National Building Museum, Nancy Bateman, Registrar, Cathy Frankel, Vice President for Exhibitions and Collections, and G. -

10/09 Bulletin

THE SEA RANCH ASSOCIATION MONTHLY BBulletinulletin October 2009 No. 426 SEPTEMBER 19 COMMUNITY MANAGER’S REPORT BOARD MEETING SUMMARY It has been a short time that I have been serving as your On September 19, 2009, The Sea Ranch Board of Interim Community Manager, and in that time I have Directors completed an agenda which included one come to appreciate the tremendous complexity of our item of new business. Association’s business. Since my September 1, 2009 official start date, some of the ANNOUNCEMENTS activities and issues that have involved the Community Manager include: Chair Retzer reported to the membership on the Board of Directors’ retreat held on September 5. • Bluff erosion The retreat was facilitated by Michael Kisslinger of • Water rates and Water Company governance forms North Coast Opportunities and included discussion • Several unusual litigation cases about the roles and responsibilities of a governing • Five special Board of Directors meetings, four involved board; the guiding principles and shared purposes with selecting a search firm for the new Community under which the Board operates; and guidelines Manager recruitment and one day-long Board retreat regarding the policy-making duties of the Board • Improvements to the Board meeting facilities and the operational functions of the Community • Road resurfacing Manager and Association staff. The Board affirmed • Swimming pool hours of operation that the Association exists to protect the common • Review of financial statements and investment activities interests of its members and concurred in its desire • Website changes for an ethical, effective and well-run Association • Responses to a variety of member concerns that is supportive of a participatory community • Meetings with some of the Operations and Policy and a steward of The Sea Ranch concept. -

Lawrence Halprin 1

SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL September/October HISTORIANS/ SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA CHAPTER NEWS 2017 Lawrence Halprin 1 President’s Letter 2 Soriano Salon 3 Authors on Architecture 4 IN THIS ISSUE Architecture Quiz Answers 6 Rock Study, 1956. Study, Rock Lawrence Halprin: Alternative Scores SAH/SCC Gallery Talk & Tour, Los Angeles Sunday, October 1, 2017, 3-5PM Spend a fall afternoon with SAH/SCC as we explore the work of legendary landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, FASLA. SAH/SCC Life Member and gallery owner Edward Cella will take us on a behind-the-scenes look at his new exhibition, “Lawrence Halprin: Alternative Scores—Drawing From Life” at Edward Cella Art + Architecture. Cella is opening up the gallery special for SAH/ SCC on a Sunday. Movement Study, 1970. Images: courtesy of Edward Cella Art + Architecture Cella of Edward Images: courtesy Sea Ranch, 1980. Pandanus Tree, Purvis Bay, Florida Islands, 1943.w Brooklyn-born Halprin (1916-2009) was educated at Cornell University and the University Alternative Scores—Drawing From Life” runs of Wisconsin before studying at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design with László concurrently with the A+D Museum’s “The Moholy-Nagy, Walter Gropius, FAIA, and Marcel Breuer, FAIA. By the mid-1960s, Lawrence Landscape Architecture of Lawrence Halprin,” Halprin & Associates gained recognition for urban landscape redevelopment projects, as well the travelling exhibition organized by The as for his work at the northern California community of Sea Ranch (Moore Lyndon Turnbull Cultural Landscape Foundation. Whitaker, 1964). The exhibition features the breadth of Halprin’s drawing during several decades. “Halprin’s Lawrence Halprin—Sunday, October 1, 2017; 3-5PM; daily practice of drawing was a means to not only record his diverse visual experiences, but was Edward Cella Art + Architecture, 2754 S.