The Remote Effect of Typhoon Megi (2010) on Precipitation Over Taiwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review Vol. 4

Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes (SEPLS) and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4 i Citation UNU-IAS and IGES (eds.) 2018, Sustainable Use of Biodiversity in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes and Seascapes and its Contribution to Effective Area-based Conservation (Satoyama Initiative Thematic Review vol. 4), United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability, Tokyo. © United Nations University ISBN (Print): 978-92-808-4643-0 ISBN (E-version): 978-92-808-4592-1 Editors Suneetha M. Subramanian Evonne Yiu Beria Leimona Editorial support Yohsuke Amano Ikuko Matsumoto Federico Lopez-Casero Michaelis Yasuo Takahashi Rajarshi Dasgupta Kana Yoshino William Dunbar Raffaela Kozar English proofreading Susan Yoshimura Design/Printing Xpress Print Pte Ltd Cover photo credits (From top to bottom): SGP/COMDEKS Indonesia, Fausto O. Sarmiento, Mayra Vera, Sebastian Orjuela-Salazar Satoyama Initiative The Satoyama Initiative is a global effort, first proposed jointly by the United Nations University and the Ministry of the Environment of Japan (MOEJ), to realize ”societies in harmony with nature” and contribute to biodiversity conservation through the revitalization and sustainable management of ”socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes” (SEPLS). The United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS) serves as the Secretariat of the International Partnership for the Satoyama Initiative (IPSI). The activities of the IPSI Secretariat are made possible through the financial contribution of the Ministry of the Environment, Japan. -

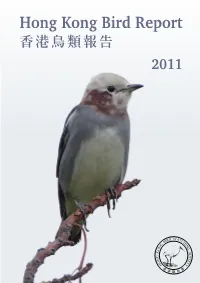

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011

Hong Kong Bird Report 2011 Hong Kong Bird Report 香港鳥類報告 2011 香港鳥類報告 Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM Birdview report 2009-2010_MINOX.indd 1 5/7/12 1:46 PM 防雨水設計 8x42 EXWP I / 10x42 EXWP I • 8倍放大率 / 10倍放大率 • 防水設計, 尤合戶外及水上活動使用 • 密封式內充氮氣, 有效令鏡片防霞防霧 • 高折射指數稜鏡及多層鍍膜鏡片, 確保影像清晰明亮 • 能阻隔紫外線, 保護視力 港澳區代理:大通拓展有限公司 荃灣沙咀道381-389號榮亞工業大廈一樓C座 電話:(852) 2730 5663 傳真:(852) 2735 7593 電郵:[email protected] 野 外 觀 鳥 活 動 必 備 手 冊 www.wanlibk.com 萬里機構wanlibk.com www.hkbws.org.hk 觀鳥.indd 1 13年3月12日 下午2:10 Published in Mar 2013 2013年3月出版 The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 7C, V Ga Building, 532 Castle Peak Road , Lai Chi Kok, Kowloon , Hong Kong, China 中國香港九龍荔枝角青山道532號偉基大廈7樓C室 (Approved Charitable Institution of Public Character) (認可公共性質慈善機構) Editors: John Allcock, Geoff Carey, Gary Chow and Geoff Welch 編輯:柯祖毅, 賈知行, 周家禮, Geoff Welch 版權所有,不准翻印 All rights reserved. Copyright © HKBWS Printed on 100% recycled paper with soy ink. 全書採用100%再造紙及大豆油墨印刷 Front Cover 封面: Chestnut-cheeked Starling Agropsar philippensis 栗頰椋鳥 Po Toi Island, 5th October 2011 蒲台島 2011年10月5日 Allen Chan 陳志雄 Hong Kong Bird Report 2011: Committees The Hong Kong Bird Watching Society 香港觀鳥會 Committees and Officers 2013 榮譽會長 Honorary President 林超英先生 Mr. Lam Chiu Ying 執行委員會 Executive Committee 主席 Chairman 劉偉民先生 Mr. Lau Wai Man, Apache 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳祖南博士 Dr. Ng Cho Nam 副主席 Vice-chairman 吳 敏先生 Mr. Michael Kilburn 義務秘書 Hon. Secretary 陳慶麟先生 Mr. Chan Hing Lun, Alan 義務司庫 Hon. Treasurer 周智良小姐 Ms. Chow Chee Leung, Ada 委員 Committee members 李慧珠小姐 Ms. Lee Wai Chu, Ronley 柯祖毅先生 Mr. -

Ensemble Forecast Experiment for Typhoon

Ensemble Forecast Experiment for Typhoon Quantitatively Precipitation in Taiwan Ling-Feng Hsiao1, Delia Yen-Chu Chen1, Ming-Jen Yang1, 2, Chin-Cheng Tsai1, Chieh-Ju Wang1, Lung-Yao Chang1, 3, Hung-Chi Kuo1, 3, Lei Feng1, Cheng-Shang Lee1, 3 1Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute, NARL, Taipei 2Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, National Central University, Chung-Li 3Dept. of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei ABSTRACT The continuous torrential rain associated with a typhoon often caused flood, landslide or debris flow, leading to serious damages to Taiwan. Therefore the quantitative precipitation forecast (QPF) during typhoon period is highly needed for disaster preparedness and emergency evacuation operation in Taiwan. Therefore, Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute (TTFRI) started the typhoon quantitative precipitation forecast ensemble forecast experiment in 2010. The ensemble QPF experiment included 20 members. The ensemble members include various models (ARW-WRF, MM5 and CreSS models) and consider different setups in the model initial perturbations, data assimilation processes and model physics. Results show that the ensemble mean provides valuable information on typhoon track forecast and quantitative precipitation forecasts around Taiwan. For example, the ensemble mean track captured the sharp northward turning when Typhoon Megi (2010) moved westward to the South China Sea. The model rainfall also continued showing that the total rainfall at the northeastern Taiwan would exceed 1,000 mm, before the heavy rainfall occurred. Track forecasts for 21 typhoons in 2011 showed that the ensemble forecast has a comparable skill to those of operational centers and has better performance than a deterministic prediction. With an accurate track forecast for Typhoon Nanmadol, the ability for the model to predict rainfall distribution is significantly improved. -

What Causes the Extremely Heavy Rainfall in Taiwan During Typhoon Morakot (2009)?

ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCE LETTERS Atmos. Sci. Let. 11: 46–50 (2010) Published online 1 February 2010 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/asl.255 What causes the extremely heavy rainfall in Taiwan during Typhoon Morakot (2009)? Xuyang Ge,1*TimLi,1 Shengjun Zhang,1,2 and Melinda Peng3 1International Pacific Research Center, SOEST, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI, USA 2State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing, China 3Marine Meteorology Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey, CA, USA *Correspondence to: Abstract Dr Xuyang Ge, University of Hawaii, 1680 East-West Road, Despite its category-2 intensity only, Typhoon (tropical cyclone in the Western Pacific) POST Building 401, Honolulu, Morakot produced a record-breaking rainfall in Taiwan. A cloud-resolving model is used to Hawaii 96822, USA. simulate this extreme rainfall event and understand the dynamic aspect under this event. E-mail: [email protected] Due to the interaction between Morakot and a monsoon system, a peripheral gale force monsoon surge appears to the south of Taiwan. The monsoon surge remains even in a sensitivity experiment in which Taiwan terrain is reduced. However, the rainfall amount in Taiwan is greatly reduced without high topography over Taiwan, suggesting the important role the local topography plays in producing heavy rainfall. The overall numerical results Received: 22 September 2009 indicate that it is the interaction among the typhoon, monsoon system, and local terrain that Revised: 29 November 2009 led to this extreme event. Copyright 2010 Royal Meteorological Society Accepted: 2 December 2009 Keywords: heavy rainfall; typhoon 1. Introduction may have a great impact on TC genesis and subse- quent motion. -

Chun-Chieh Wu (吳俊傑) Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 1

Chun-Chieh Wu (吳俊傑) Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University No. 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Rd., Taipei 106, Taiwan Telephone & Facsimile: (886) 2-2363-2303 Email: [email protected], WWW: http://typhoon.as.ntu.edu.tw Date of Birth: 30 July, 1964 Education: Graduate: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ph.D., Department of Earth Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, May 1993 Thesis under the supervision of Professor Kerry A. Emanuel on "Understanding hurricane movement using potential vorticity: A numerical model and an observational study." Undergraduate: National Taiwan University, B.S., Department of Atmospheric Sciences, June 1986 Recent Positions: Professor and Chairman Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 2008 to present Director NTU Typhoon Research Center January 2009 to present Adjunct Research Scientist Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University July 2004 - present Professor Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 2000 to 2008 Visiting Fellow Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton University January – July, 2004 (on sabbatical leave from NTU) Associate Professor Department of Atmospheric Sciences, National Taiwan University August 1994 to July 2000 Visiting Research Scientist Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory, Princeton University August 1993 – November 1994; July to September 1995 1 Awards: Gold Bookmarker Prize Wu Ta-You Popular Science Book Prize in Translation Wu Ta-You Foundation, 2008 Outstanding Teaching Award, National Taiwan University, 2008 Outstanding Research Award, National Science Council, 2007 Research Achievement Award, National Taiwan Univ., 2004 University Teaching Award, National Taiwan University, 2003, 2006, 2007 Academia Sinica Research Award for Junior Researchers, 2001 Memberships: Member of the American Meteorological Society. Member of the American Geophysical Union. -

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Probabilistic Evaluation of the Dynamics and Prediction of Supertyphoon Megi (2010)

1562 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 28 Probabilistic Evaluation of the Dynamics and Prediction of Supertyphoon Megi (2010) CHUANHAI QIAN Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, and National Meteorological Center, Beijing, China, and Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania FUQING ZHANG AND BENJAMIN W. GREEN Department of Meteorology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania JIN ZHANG National Meteorological Center, Beijing, China XIAQIONG ZHOU NOAA/NCEP, College Park, Maryland (Manuscript received 21 November 2012, in final form 21 July 2013) ABSTRACT Supertyphoon Megi was the most intense tropical cyclone (TC) of 2010. Megi tracked westward through the western North Pacific and crossed the Philippines on 18 October. Two days later, Megi made a sharp turn to the north, an unusual track change that was not forecast by any of the leading operational centers. This failed forecast was a consequence of exceptionally large uncertainty in the numerical guidance—including the operational ensemble of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)—at various lead times before the northward turn. This study uses The Observing System Research and Predictability Experiment (THORPEX) Interactive Grand Global Ensemble dataset to examine the uncertainties in the track forecast of the ECMWF operational ensemble. The results show that Megi’s sharp turn is sensitive to its own movement in the early period, the size and structure of the storm, the strength and extent of the western Pacific subtropical high, and an approaching eastward-moving midlatitude trough. In particular, a larger TC (in addition to having a stronger beta effect) may lead to a stronger erosion of the southwestern extent of the subtropical high, which will subsequently lead to an earlier and sharper northward turn. -

7 the Analysis of Storm Surge in Manila Bay, the Philippines

INTERNATIONAL HYDROGRAPHIC REVIEW MAY 2019 THE ANALYSIS OF STORM SURGE IN MANILA BAY, THE PHILIPPINES By Commander C. S. Luma-ang Hydrography Branch, National Mapping and Resource Information Authority, (Philippines) Abstract In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan produced a storm surge over seven metres in San Pedro Bay in the Philippines that killed approximately 6,300 people. The event created significant public awareness on storm surges and exposed the lack of records and historical research in the Philippines. This study investigated the tidal height records during intense cyclone activities in 2016 and 2017 to provide accurate information about storm surge development in the largest and most populated coastal area in the country – Manila Bay. The results of this investigation indicated that there are consistencies in the characteristics of tropical cyclones that produce larger storm surges. The results also show that actual storm surge heights are generally smaller than predicted height values. Résumé En 2013, le typhon Haiyan a provoqué une onde de tempête de plus de sept mètres dans la Baie de San Pedro aux Philippines, faisant près de 6 300 victimes. Cet événement a provoqué une importante sensibilisation du public envers les ondes de tempête et a mis en évidence le manque d’archives et de recherches historiques aux Philippines. La présente étude a examiné les enregistrements des hauteurs des marées au cours d’activités cycloniques intenses en 2016 et 2017 afin de fournir des informations précises sur le développement d’ondes de tempête dans la zone côtière la plus étendue et la plus peuplée du pays, la Baie de Manille. -

NICAM Predictability of the Monsoon Gyre Over The

EARLY ONLINE RELEASE This is a PDF of a manuscript that has been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. As the article has not yet been formatted, copy edited or proofread, the final published version may be different from the early online release. This pre-publication manuscript may be downloaded, distributed and used under the provisions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license. It may be cited using the DOI below. The DOI for this manuscript is DOI:10.2151/jmsj.2019-017 J-STAGE Advance published date: December 7th, 2018 The final manuscript after publication will replace the preliminary version at the above DOI once it is available. 1 NICAM predictability of the monsoon gyre over the 2 western North Pacific during August 2016 3 4 Takuya JINNO1 5 Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Graduate School of Science, 6 The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan 7 8 Tomoki MIYAKAWA 9 Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute 10 The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 11 12 and 13 Masaki SATOH 14 Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute 15 The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 16 17 18 19 20 Sep 30, 2018 21 22 23 24 25 ------------------------------------ 26 1) Corresponding author: Takuya Jinno, School of Science, 7-3-1, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, 27 Tokyo 113-0033 JAPAN. 28 Email: [email protected] 29 Tel(domestic): 03-5841-4298 30 Abstract 31 In August 2016, a monsoon gyre persisted over the western North Pacific and was 32 associated with the genesis of multiple devastating tropical cyclones. -

Assimilating AMSU-A Radiance Data with the WRF Hybrid En3dvar System for Track Predictions of Typhoon Megi (2010)

ADVANCES IN ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES, VOL. 32, SEPTEMBER 2015, 1231–1243 Assimilating AMSU-A Radiance Data with the WRF Hybrid En3DVAR System for Track Predictions of Typhoon Megi (2010) SHEN Feifei∗ and MIN Jinzhong Collaborative Innovation Center on Forecast and Evaluation of Meteorological Disasters, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044 (Received 28 October 2014; revised 12 December 2014; accepted 29 December 2014) ABSTRACT The impact of assimilating radiances from the Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit-A (AMSU-A) on the track prediction of Typhoon Megi (2010) was studied using the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model and a hybrid ensemble three- dimensional variational (En3DVAR) data assimilation (DA) system. The influences of tuning the length scale and variance scale factors related to the static background error covariance (BEC) on the track forecast of the typhoon were studied. The results show that, in typhoon radiance data assimilation, a moderate length scale factor improves the prediction of the typhoon track. The assimilation of AMSU-A radiances using 3DVAR had a slight positive impact on track forecasts, even when the static BEC was carefully tuned to optimize its performance. When the hybrid DA was employed, the track forecast was significantly improved, especially for the sharp northward turn after crossing the Philippines, with the flow-dependent ensemble covariance. The flow-dependent BEC can be estimated by the hybrid DA and was capable of adjusting the position of the typhoon systematically. The impacts of the typhoon-specific BEC derived from ensemble forecasts were revealed by comparing the analysis increments and forecasts generated by the hybrid DA and 3DVAR. -

On the Extreme Rainfall of Typhoon Morakot (2009)

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 116, D05104, doi:10.1029/2010JD015092, 2011 On the extreme rainfall of Typhoon Morakot (2009) Fang‐Ching Chien1 and Hung‐Chi Kuo2 Received 21 September 2010; revised 17 December 2010; accepted 4 January 2011; published 4 March 2011. [1] Typhoon Morakot (2009), a devastating tropical cyclone (TC) that made landfall in Taiwan from 7 to 9 August 2009, produced the highest recorded rainfall in southern Taiwan in the past 50 years. This study examines the factors that contributed to the heavy rainfall. It is found that the amount of rainfall in Taiwan was nearly proportional to the reciprocal of TC translation speed rather than the TC intensity. Morakot’s landfall on Taiwan occurred concurrently with the cyclonic phase of the intraseasonal oscillation, which enhanced the background southwesterly monsoonal flow. The extreme rainfall was caused by the very slow movement of Morakot both in the landfall and in the postlandfall periods and the continuous formation of mesoscale convection with the moisture supply from the southwesterly flow. A composite study of 19 TCs with similar track to Morakot shows that the uniquely slow translation speed of Morakot was closely related to the northwestward‐extending Pacific subtropical high (PSH) and the broad low‐pressure systems (associated with Typhoon Etau and Typhoon Goni) surrounding Morakot. Specifically, it was caused by the weakening steering flow at high levels that primarily resulted from the weakening PSH, an approaching short‐wave trough, and the northwestward‐tilting Etau. After TC landfall, the circulation of Goni merged with the southwesterly flow, resulting in a moisture conveyer belt that transported moisture‐laden air toward the east‐northeast. -

Dynamic Response of a Philippine Dipterocarp Forest to Typhoon Disturbance

Journal of Vegetation Science 27 (2016) 133–143 Dynamic response of a Philippine dipterocarp forest to typhoon disturbance Sandra L. Yap, Stuart J. Davies & Richard Condit Keywords Abstract Biomass; Dipterocarp forest; Forest dynamics; Forest resilience; Mortality and recruitment; Questions: Natural hazards can wreak catastrophic damage to forest ecosys- Regeneration; Tree demography; Typhoon tems. Here, the effects of typhoon disturbance on forest structure and demogra- disturbance phy of the 16-ha Palanan Forest Dynamics Plot in the northeast Philippines were examined by comparing census intervals with (1998–2004) and without Nomenclature (2004–2010) a strong typhoon. Category 4 Typhoon Imbudo, with wind gusts Co et al. (2006) exceeding 210 kph, hit Palanan in July 2003. In this study, we ask: (1) was there Received 5 August 2014 an effect of the typhoon on stand structure and biomass; (2) was there an impact Accepted 5 February 2015 on species diversity; (3) did annual mortality, growth and recruitment change Co-ordinating Editor: Kerry Woods significantly between typhoon and non-typhoon periods; and (4) did the typhoon’s impact vary with local topography, from leeward to windward sides Yap, S.L. ([email protected])1, of a ridge? Davies, S.J. (corresponding author, Location: Lowland mixed dipterocarp forest, Palanan, Isabela, Philippines. [email protected])2, Condit, R. ([email protected])3 Methods: Census data from 1998, 2004 and 2010 for all trees ≥1 cm DBH in a 1Institute of Biology, University of the 16-ha permanent plot in Palanan, Isabela, were used to assess tree demography. Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, PH 1101, Recorded in the census were species identification and measurements of DBH Philippines; and tree locations.