IN THIS ISSUE Forthcoming MHS Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memories of a Lifetime in Berkhamsted

Your Berkhamsted editorial From the Editor July 2012 The Parish Magazine of Contents St Peter's Great Berkhamsted Leader by Richard Hackworth 3 Welcome to the July issue of Your Around the town 5 Berkhamsted. Read all about us 7 The weather may still not be what we’d like for summer but in true British spirit it Back to the outdoors 9 doesn’t stop us celebrating. The jubilee weekend may have had us all reaching for The Black Ditch, the dungeon the umbrellas but the cloud did break at and the parachute 12 times for the High Street party and it was a beautiful evening for the celebrations later Sport—cricket 14 at Ashlyns School and the many street parties around town. At Ashlyns it was Christians against poverty 15 encouraging to see so many people come together from the community, picnic Hospice News 16 blankets in tow, just relaxing, chatting and enjoying being part of such a lovely town. Parish news 18 On the subject of celebrations, the Berkhamsted Games 2012 take place this Summer garden 20 month on 5th July, not forgetting of course the 2012 Olympics, and our own magazine Memories of a lifetime in is 140 years old! So, more reasons to keep Berkhamsted 23 that union jack bunting flying and carry on regardless of the great British weather. Chilterns Dog Rescue 27 To celebrate our anniversary we have two Recipe 28 articles by Dan Parry: one looking back at Berkhamsted in 1872 and another where The Last Word 31 he chats to a long-term Berkhamsted resident Joan Pheby, born in 1924, about front cover. -

“Henry VIII, a Dazzling Renaissance Prince and the Great Matter”

UNIVERSIDAD DE MAGALLANES FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS SOCIALES Y DE LA SALUD Departamento de Educación “Henry VIII, a Dazzling Renaissance Prince and the Great Matter” By: Jessica Alvarado Guerrero Gustavo Leal Navarro Jimena Montenegro Gallardo Pablo Torres Barrientos Tutor: Alicia Triviño Punta Arenas- 2010 0 ABSTRACT As the title of this monograph suggests, this research focuses on King Henry VIII’s “Great Matter”, and how relevant it was to the whole process of the English Reformation covering a period of 17 years (1530-1547). Through this analysis, this work evidences the whole process of Reformation that England went through during the XVI century. As a result, the English Church becomes independent from the authority of the Pope. The main purpose of this investigation is to carefully examine the primary and secondary facts that prompted the separation from the Catholic Church on the grounds that the Henrician Reformation developed differently, in relation to the European process. Furthermore, this work intends to unveil the true nature of King Henry VIII’s character and the way his actions, way of living, beliefs and thoughts influenced on the separation of the Church and as a result lead to the Reformation era. After all, Henry VIII was one of the most controversial political figures of all times. The most important highlights in King Henry VIII’s life are presented in order to contextualize the reader to the conditions that conducted to the most striking changes that Catholic England had undergone. Together with Henry’s Great Matter, this work also presents a complete account of the King’s personal life, to make the reader understand the decisions made by Henry in critical times, covering from the relationships with his wives, mistresses, children to his medical records, controversial aspects in his life that for most historians turned him into a tyrant while for some other, one of the greatest English Kings ever. -

Comus (A Mask Presented at Ludlow Castle) John Milton (1634) the Persons the Attendant Spirit Afterwards in the Habit of Thyrsis

Comus (A Mask Presented at Ludlow Castle) John Milton (1634) The Persons The attendant Spirit afterwards in the habit of Thyrsis Comus with his crew The Lady 1. Brother 2. Brother Sabrina, the Nymph _______________________________________ The cheif persons which presented, were The Lord Bracly, Mr. Thomas Egerton, his Brother, The Lady Alice Egerton. _______________________________________ The first Scene discovers a wilde Wood. The attendant Spirit descends or enters. BEfore the starry threshold of Joves Court My mansion is, where those immortal shapes Of bright aëreal Spirits live insphear'd In Regions milde of calm and serene Ayr, Above the smoak and stirr of this dim spot, [ 5 ] Which men call Earth, and with low-thoughted care Confin'd, and pester'd in this pin-fold here, Strive to keep up a frail, and Feaverish being Unmindfull of the crown that Vertue gives After this mortal change, to her true Servants [ 10 ] Amongst the enthron'd gods on Sainted seats. Yet som there be that by due steps aspire To lay their just hands on that Golden Key That ope's the Palace of Eternity: To such my errand is, and but for such, [ 15 ] I would not soil these pure Ambrosial weeds, With the rank vapours of this Sin-worn mould. But to my task. Neptune besides the sway Of every salt Flood, and each ebbing Stream, Took in by lot 'twixt high, and neather Jove, [ 20 ] Imperial rule of all the Sea-girt Iles Source URL: http://www.dartmouth.edu/~milton/reading_room/comus/index.shtml Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/engl402/ Attributed to: [Thomas H. -

The Castle Studies Group Bulletin

THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP BULLETIN Volume 21 April 2016 Enhancements to the CSG website for 2016 INSIDE THIS ISSUE The CSG website’s ‘Research’ tab is receiving a make-over. This includes two new pages in addition to the well-received ‘Shell-keeps’ page added late last News England year. First, there now is a section 2-5 dealing with ‘Antiquarian Image Resources’. This pulls into one News Europe/World hypertext-based listing a collection 6-8 of museums, galleries, rare print vendors and other online facilities The Round Mounds to enable members to find, in Project one place, a comprehensive view 8 of all known antiquarian prints, engravings, sketches and paintings of named castles throughout the News Wales UK. Many can be enlarged on screen 9-10 and downloaded, and freely used in non-commercial, educational material, provided suitable credits are given, SMA Conference permissions sought and copyright sources acknowledged. The second page Report deals with ‘Early Photographic Resources’. This likewise brings together 10 all known sources and online archives of early Victorian photographic material from the 1840s starting with W H Fox Talbot through to the early Obituary 20th century. It details the early pioneers and locates where the earliest 11 photographic images of castles can be found. There is a downloadable fourteen-page essay entitled ‘Castle Studies and the Early Use of the CSG Conference Camera 1840-1914’. This charts the use of photographs in early castle- Report related publications and how the presentation and technology changed over 12 the years. It includes a bibliography and a list of resources. -

Manuscript: “Sanctifying Rites in Milton's a Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle, 1634”

Manuscript: “Sanctifying rites in Milton’s A Masque Presented at Ludlow Castle, 1634”1 Published in Christianity & Literature 2019, Vol. 68(2) 193–212 Reading Stanley Fish’s chapters on Comus in How Milton Works is a hermeneutical challenge not unlike reading Milton himself. Fish’s picture of the Lady is the crux of his approach, and it is a picture whose edges seem to shift depending on the reader’s stance. This may be intentional, a portrayal of the “double perspective” which for Fish is the poem’s basic narrative technique: “The form of these questions is ‘either-or,’ but the answer in every case is ‘both-and’: the earth is both a pinfold and a gem, depending on whether you are tied to it by ‘low-thoughted care’ or live, at least in sprit, in ‘Regions mild of calm and serene Air’ (6, 4).”2 As such, misreading Fish may be identical to misreading Milton.3 So that the reader may judge, I want to begin by briefly developing what I understand to be Fish’s argument. Picking up at the point where Comus has immobilized the Lady and left her with nothing by way of outside support, Fish writes: “Yet, as it turns out, she is left with everything— everything that matters. This is what is meant when she says to Comus, ‘Thou canst not touch the freedom of my mind’ (663), or, in other words, ‘All of this—my weakness, your strength, the entire situation as it seems to be—is beside the point. I may be imprisoned in every sense you can conceive, but in truth I am free.’”4 What primarily matters is how one inhabits Nature and the natural self; “Temperance, then, is a positive and liberating action” and Nature’s value “is a function of your relationship to it—a prison if you allow yourself to be confined within its 1 I am grateful to David Aers, Matthew Smith, and the anonymous readers and editorial staff of Christianity and Literature for their helpful input on earlier drafts of this essay. -

Herts Archaeology -- Contents

Hertfordshire Archaeology and History contents From the 1880s until 1961 research by members of the SAHAAS was published in the Society’s Transactions. As part of an extensive project, digitised copies of the Transactions have been published on our website. Click here for further information: https://www.stalbanshistory.org/category/publications/transactions-1883-1961 Since 1968 members' research has appeared in Hertfordshire Archaeology published in partnership with the East Herts Archaeological Society. From Volume 14 the name was changed to Hertfordshire Archaeology and History. The contents from Volume 1 (1968) to Volume 18 (2016-2019) are listed below. If you have any questions about the journal, please email [email protected]. 1 Volume 1 1968 Foreword 1 The Date of Saint Alban John Morris, B.A., Ph.D. 9 Excavations in Verulam Hills Field, St Albans, 1963-4 Ilid E Anthony, M.A., Ph.D., F.S.A. 51 Investigation of a Belgic Occupation Site at A G Rook, B.Sc. Crookhams, Welwyn Garden City 66 The Ermine Street at Cheshunt, Herts. G R Gillam 68 Sidelights on Brasses in Herts. Churches, XXXI: R J Busby Furneaux Pelham 76 The Peryents of Hertfordshire Henry W Gray 89 Decorated Brick Window Lintels Gordon Moodey 92 The Building of St Albans Town Hall, 1829-31 H C F Lansberry, M.A., Ph.D. 98 Some Evidence of Two Mesolithic Sites at Bishop's A V B Gibson Stortford 103 A late Bronze Age and Romano-British Site at Thorley Wing-Commander T W Ellcock, M.B.E. Hill 110 Hertfordshire Drawings of Thomas Fisher Lieut-Col. -

Castles Map of Scotland Free

FREE CASTLES MAP OF SCOTLAND PDF Collins Maps | 1 pages | 01 Aug 2013 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007508532 | English | London, United Kingdom Castles in Scotland Map | From the smaller motte and bailey earthworks to Castles Map of Scotland world famous Leeds Castle, all have been geotagged onto the Google Map below. We have also included a short synopsis of each of the castles, including the history behind them and who they are now owned by. Although we have attempted to Castles Map of Scotland the most comprehensive listing on the internet, there is a small chance that a few castles may have slipped through our net. Looking to stay in one of these fabulous castles? Features a virtual tour! Eynsford Castle is a rare survival of an early Norman castle, unaltered by later building works. Its location close to London also makes it a great venue for anyone looking for a day trip out from the capital! Here we…. Hemyock Castle is tucked away behind high stone walls in Castles Map of Scotland peaceful village of Hemyock in the Blackdown Hills in…. Please tell us a little bit about the attraction, site or destination Castles Map of Scotland we have missed. Not required. Related articles. Eynsford Castle, Kent. Camelot, Court of King Arthur. Hemyock Castle. Next article. We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. The influence of Bishop Burnell was such that this little Shropshire village twice hosted the English Parliament, first in and again in All that remains open to the public is the shell of the former private residence. -

It's Never Too Late!

Discover Shropshire it’s never too late! There is no such thing as “too old to exercise”. Whatever your age or fitness, you can benefit from doing a bit Ludlow Country Walks more physical activity. Try to get out and walk as much as possible within your own limitations Round the Castle Walls Start at your own level Length: ½ mile Walk 3 There is no point wearing yourself out on your first walk. Start gradually, set yourself small targets and goals and build slowly from there. Small changes can make a big difference, the Time: Allow ½ an hour with stops most important thing is to make a start. Start & Parking: Castle Square, Town Centre Build walking into your daily routine Any activity is better than none, but to get the most benefit you need to do at least Walk Grade: Easy, dry hard paths, one moderate hill 30minutes moderate physical activity on at least 5 days of the week. Moderate activity is anything which involves: You should aim to reach a single session of 30mins but you can break ● Breathing a little faster this down into: ● Having a slightly faster heart beat ● 3 x 10minutes ● Feeling warmer ● 2 x 15minutes Any health benefits you have gained will be lost if you don’t continue to be active Listen to your body If you feel any dizziness or pain whilst walking, slow down or stop completely and take a rest. If the problem continues, consult your doctor before walking again. Ludlow Parish Path Partnership (P3) are a group who volunteer in partnership with Shropshire Council to help improve and promote the Public Rights of Way in and around the parish of Ludlow. -

Poor Wall Swatch

Dacorum Festival of Culture Other Festival events to look What is the Festival of Culture? out for in the future: Tring Hockey Club Taster Sessions The Nation is gearing up for the London 2012 Olympic Programme of Events June - September 2011 Tag Rugby Tournament Games. That's why across Dacorum, a festival, celebrating Boxmoor and District Angling our culture will showcase the arts, sport, heritage and An exciting programme Badminton Taster sessions leisure in the Borough. We hope to encourage of, arts, sports, Berkhamsted Youth Theatre Present, The Witches by Roald Dahl everyone to get involved and celebrate the Olympic and heritage and leisure Berkhamsted Choral Society - Christmas Concert Paralympic Games. events throughout the Dacorum Heritage Trust - Sports Heritage Project Children's Trust Partnership Events A programme of new, funded events together with some Borough between Youth Choirs workshops established favourites is planned to take place between June 2011 and Children's Trust Partnership Events June 2011 and December 2012. December 2012. Flametree & Old Town Hall - Cultural Fashions and Music Project Together they can have real impact and make a Age Concern - 1948 Olympic Memories Project sustainable difference to the wellbeing of the whole Women's Golf Day at Little Hay Golf Club community. A central aim of the programme is to support Flametree & Old Town Hall - Cultural Fashions and Music Project health and exercise programmes, assist learning, and Community Bowls Taster sessions The Hemel Hempstead and South African School Cultural Exchange personal development, involve the public in arts and Grand Water Festival 2012 local heritage and utilise our public facilities and open Tennis Taster Days spaces. -

Extending Histories: from Medieval Mottes to Prehistoric Round Mounds

University of Reading Extending Histories: from Medieval Mottes to Prehistoric Round Mounds Berkhamsted Castle, Hertfordshire Interim Report Phil Stastney and Elaine Jamieson Document Control Version Date Compiler Status 1.0 PS, EJ Interim Report Executive Summary Berkhamsted Castle is located on the north side of the town of Berkhamsted and sits in the Akeman Street gap through the Chiltern Hills, in the county of Hertfordshire. In 2015, as part of the Leverhulme Trust funded project Extending Histories: from Medieval Mottes to Prehistoric Round Mounds, staff from the University of Reading undertook archaeological investigations at the site. Fieldwork included drilling a borehole through the castle mound down to the old ground surface, as well as the detailed analytical earthwork survey of the upstanding mound remains. This fieldwork was followed by a programme of scientific dating and palaeoenvironmental analysis. The results of this work indicate that the castle motte, which is over 14m high, was constructed from local geological material. Due to the poor quality of the samples retrieved from the mound for radiocarbon dating, only a minimum age for the construction of the motte has been ascertained – sometime after cal AD 689-885 (95% confidence) – and it is highly probable that the mound is later in date. The earthwork evidence indicates that the motte may originally have has a series of structures on it south-western side and was surmounted by a stone keep up to 18m in diameter. 1. INTRODUCTION AND RESEARCH BACKGROUND This report describes the initial result of archaeological investigations carried out at Berkhamsted Castle, Hertfordshire, as part of the Extending Histories: from Medieval Mottes to Prehistoric Round Mounds project (The Round Mounds project for short), a University of Reading research project funded by The Leverhulme Trust. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Tuesday Volume 673 17 March 2020 No. 42 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 17 March 2020 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2020 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 779 17 MARCH 2020 780 right across the world to give them the support and House of Commons advice that they need. I will be making a further statement after oral questions. Tuesday 17 March 2020 Dr Caroline Johnson: What discussions is my right hon. Friend having with his counterparts in countries The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock such as the United States, Australia and Israel, which are working actively on a vaccine for covid-19, so that we can share information from our research and develop PRAYERS a vaccine more quickly together? Dominic Raab: I thank my hon. Friend for that question [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] —I know how expert she is in this field. We are, of course, emphasising the importance of vaccine research and encouraging the scientific community to co-ordinate. In particular, we want to prioritise collaboration on Oral Answers to Questions vaccineresearch,includingwithfinancingandco-ordination throughtheCoalitionforEpidemicPreparednessInnovations fund. FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH OFFICE Michael Fabricant: SARS—severe acute respiratory syndrome—swine flu and now coronavirus are all thought The Secretary of State was asked— to have emanated from unsanitary wet butcheries in east Asia and China. What can my right hon. Friend do Covid-19 to co-ordinate an effort—perhaps after all this is over— to prevent any such disease from ever starting in such 1. -

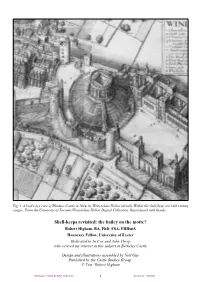

Shell Keeps at Carmarthen Castle and Berkeley Castle

Fig. 1. A bird's-eye view of Windsor Castle in 1658, by Wenceslaus Hollar (detail). Within the shell-keep are 14th century ranges. From the University of Toronto Wenceslaus Hollar Digital Collection. Reproduced with thanks. Shell-keeps revisited: the bailey on the motte? Robert Higham, BA, PhD, FSA, FRHistS Honorary Fellow, University of Exeter Dedicated to Jo Cox and John Thorp, who revived my interest in this subject at Berkeley Castle Design and illustrations assembled by Neil Guy Published by the Castle Studies Group. © Text: Robert Higham Shell-keeps re-visited: the bailey on the motte? 1 Revision 21 - 19/04/2016 Fig. 2. Lincoln Castle, Lucy Tower, following recent refurbishment. Image: Neil Guy. Abstract Scholarly attention was first paid to the sorts of castle ● that multi-lobed towers built on motte-tops discussed here in the later 18th century. The “shell- should be seen as a separate form; that truly keep” as a particular category has been accepted in circular forms (not on mottes) should be seen as a academic discussion since its promotion as a medieval separate form; design by G.T. Clark in the later 19th century. Major ● that the term “shell-keep” should be reserved for works on castles by Ella Armitage and A. Hamilton mottes with structures built against or integrated Thompson (both in 1912) made interesting observa- with their surrounding wall so as to leave an open, tions on shell-keeps. St John Hope published Windsor central space with inward-looking accommodation; Castle, which has a major example of the type, a year later (1913).