Building Houston's Competitive Edge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rider Guide / Guía De Pasajeros

Updated 02/10/2019 Rider Guide / Guía de Pasajeros Stations / Estaciones Stations / Estaciones Northline Transit Center/HCC Theater District Melbourne/North Lindale Central Station Capitol Lindale Park Central Station Rusk Cavalcade Convention District Moody Park EaDo/Stadium Fulton/North Central Coffee Plant/Second Ward Quitman/Near Northside Lockwood/Eastwood Burnett Transit Center/Casa De Amigos Altic/Howard Hughes UH Downtown Cesar Chavez/67th St Preston Magnolia Park Transit Center Central Station Main l Transfer to Green or Purple Rail Lines (see map) Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Westbound – Central Station Capitol Eastbound – Central Station Rusk Eastbound Theater District to Magnolia Park Hacia el este Magnolia Park Main Street Square Bell Westbound Magnolia Park to Theater District Downtown Transit Center Hacia el oeste Theater District McGowen Ensemble/HCC Wheeler Transit Center Museum District Hermann Park/Rice U Stations / Estaciones Memorial Hermann Hospital/Houston Zoo Theater District Dryden/TMC Central Station Capitol TMC Transit Center Central Station Rusk Smith Lands Convention District Stadium Park/Astrodome EaDo/Stadium Fannin South Leeland/Third Ward Elgin/Third Ward Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales TSU/UH Athletics District Northbound Fannin South to Northline/HCC UH South/University Oaks Hacia el norte Northline/HCC MacGregor Park/Martin Luther King, Jr. Southbound Northline/HCC to Fannin South Palm Center Transit Center Hacia el sur Fannin South Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Eastbound Theater District to Palm Center TC Hacia el este Palm Center Transit Center Westbound Palm Center TC to Theater District Hacia el oeste Theater District The Fare/Pasaje / Local Make Your Ride on METRORail Viaje en METRORail Rápido y Fare Type Full Fare* Discounted** Transfer*** Fast and Easy Fácil Tipo de Pasaje Pasaje Completo* Descontado** Transbordo*** 1. -

Isabella Brochure Web FF.Pdf

Own a Piece of Midtown HOUSTON'S DEVELOPER OF THE YEAR* PRESENTS Designed with a unique, upscale, urban lifestyle in mind, The Isabella at Midtown is elegant, affordable and centrally located at 4001 Main Street. This 165-plus condominium mid-rise building emerges as an architectural joy and jewel of the neighborhood, and stands as the ideal choice for first-time homebuyers and anyone wanting to simplify and enrich their lifestyle. *Houston Agent Magazine A Lux Life OUTSIDE AND IN PRELIMINARY DESIGN The Isabella at Midtown offers residents unique, exotic, urban and comfortable living in the most vibrant of growing neighborhoods in the center of the nation’s fourth-largest city. From a dynamic, exterior of color to the lavish European-inspired interiors and classic 165 city views, Houston’s Main Street condo community offers constant LUXURIOUS luxury and convenience to residents. HOMES ach detail of The Isabella at Midtown is thoughtfully designed and built so you have a Eluxurious experience in your own community and home. Enter the common areas and you are surrounded by sophistication and luxury: the central courtyard features an in-house fitness club, outdoor pool with hot tub, and owners' lounge equipped with a fully-functioning kitchen, large-screen TV, and entertaining. 5,500 OUTDOOR TERRACE Enjoy open-floor plans in your home and be assured that elegance, comfort and ease are AND POOL DECK* the heart of your new home design. Each home has a private outdoor space, some with stunning panoramic views of Houston’s ever-changing distinctive -

Capital Metro Presentation

Project Connect: The Future of Transportation in Austin 1 PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION IN AUSTIN: The “Why” and a Little Background 2 THE GEOMETRY OF TRANSIT Historic Population Growth Austin MSA Population 3 THE GEOMETRY OF TRANSIT Bus 4 THE GEOMETRY OF TRANSIT Bus Bike 5 THE GEOMETRY OF TRANSIT Bus Bike Car 6 RAIL TRANSPORTATION IN AUSTIN Houston & Texas Central Austin & Northwestern Missouri Pacific Railroad 1871 –First Rail Connection 1881 –Austin to Llano 1970 –Final Texas Eagle 7 RAIL TRANSIT IN AUSTIN Austin Rapid Transit Railway Austin Transit Company Capital MetroRail (Red Line) 1889 (1913 Photo) 1940 –Final Streetcar 2010 –Start of Service 8 AUSTIN TRANSIT PARTNERSHIP: Implementing the Project Connect Vision 9 Initial Investment – Adopted July 27, 2020 10 Initial Investment – Adopted July 27, 2020 11 Initial Investment – Adopted July 27, 2020 12 Comprehensive Transit Plan New Rail System Expanded Bus Service LIGHT RAIL REGIONAL RAIL 4 new MetroRapid routes; high‐ frequency bus service with priority treatments. 42 miles, 65 stations 10 new stations, with planned conversion to Light Rail Downtown Transit Tunnel 3 new MetroExpress commuter routes 9 New Park & Rides + 1 New Transit Center All‐Electric Bus Fleet 15 new neighborhood MetroBike integration circulator zones with on‐demand pick‐up 13 Light Rail Transit Conceptual Illustration 14 v3 DELIBERATIVE DRAFT 15 New Rail System CW11 CW10 Light rail to connect CW12 north and south Austin. From Tech Ridge (initially from North Lamar and U.S. 183) and extending to Slaughter (initially to Stassney Lane. 16 Slide 16 CW10 delete planned Couch, David W., 12/14/2020 CW11 Need to reflect total length of Orange line with the initial operating segment identified. -

Twenty Years of Urban Redevelopment December 31, 2014

MIDTOWN REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY HOUSTON, TEXAS TWENTY YEARS OF URBAN REDEVELOPMENT DECEMBER 31, 2014 To: The Residents and Stakeholders of Midtown As we recognize our twentieth year, this report details the growth of Midtown since its creation by describing some of our projects and our plan for the future. It also provides an easy-to-read summary of the finances of the Authority and the Tax Increment Redevelopment Zone No. 2 (“TIRZ #2” or the “Zone”) for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2014 and the budget for fiscal year 2015. Midtown seeks to be an example of a sustainable urban community. Both residents and visitors benefit from Midtown’s urban, mixed-use environment, enhanced with pedestrian-oriented sidewalks, decorative street lighting and streets designed for easy traffic flow whether on foot, on bicycles or in vehicles. Midtown uses one-third of its tax increment revenue to induce and develop affordable housing. The Authority has developed an affordable housing strategy that focuses on land assembly and affordable housing development to encourage mixed use, transit-oriented affordable housing development. Our efforts reflect the collaboration and financial participation of the City of Houston, Harris County, the Houston Independent School District and the Houston Community College System along with the direction of State Senator Rodney Ellis and State Representative Garnet Coleman – Midtown’s partners in the leadership, funding and participation in the Zone. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact me. Sincerely, Matt Thibodeaux Executive Director 410 Pierce Street, Suite 355, Houston, TX 77002 Phone: 713-526-7577 Midtown Redevelopment Authority Phone 713.526.7577 Fax 713.526.7519 410 Pierce St, Suite 355, Houston, TX 77002 www.houstonmidtown.com MIDTOWN REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Position I William J. -

Onwenu, Ravella Win SA Races Amid High Turnout

VOLUME 101, ISSUE NO. 22 | STUDENT˜RUN SINCE 1916 | RICETHRESHER.ORG | WEDNESDAY, MARCH 22, 2017 Housing guide: Tips for students looking to live o° campus see insert p.7 VIETNAMESE FOOD DISTRIBUTION MARCH REMIXED MATTERS MADNESS Les Ba’get serves high-quality Humanities courses critical to Women’s basketball rallies to reach the banh mis STEM education final four of the WBI ˜°° AE ˛. ˘˘ ˜°° O˛˜ ˛. ˝ ˜°° S˛˙ˆˇ˜ ˛. ˘ From San Francisco to D.C., students spent spring break Baker chef CAPTURING ASBs exploring various social issues within communities mourned ˜°˛˝°˙ˆ ˇ˛ ˆ˘° ˇˇ In D.C., students explored gender equality and ˛ˆˇ . ˛˙ˇ°˙° Students headed to San Francisco to after tragic attended a protest with Elizabeth Warren. understand stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS. death A T A˙˙ˇ˙˘˘ N°˛˙ Eˆˇ˘˜ Baker College Kitchen Cook II Essence Derouen passed away this past Sunday, March 9. According to ABC 13, she was an innocent bystander shot while sitting in her car, on her way home. The 21-year- old is survived by her 6-year-old son. According to a Facebook post from Rice University Housing and Dining, the Baker College Kitchen closed on Monday, March 20 to pay tribute to her memory. For the past two years, Derouen has worked with the Baker Kitchen team, having joined H&D ˙˜ ˙˜ ˜°ˇ ˜˜ˇ°˜˛ At the Rio Grande Valley, students explored issues of as a culinary intern several years Students compared Colorado’s resource accessibility immigration and education inequality that a˜ect the area. ago. According to a GoFundMe for individuals with disabilities to that of Houson. -

Houston Loft Packet

Downtown / Midtown Lofts & Condos Paige Martin Broker Associate Keller Williams Realty 713-384-5177 [email protected] Benefits Of Loft & Downtown Condo Living 1. Over 75 restaurants, shops, theaters and entertainment venues within a few blocks. Downtown residents have easy access to the 2nd largest theater district in the US, Market Square Park, Minute Maid Field, Discovery Green, Toyota Center and so much more. In addition, over 20 restaurants & bars opened within the last few years, offering a wide variety of food, drink and entertainment options - all within a few blocks. 2. Short & easy commute to Houston’s largest employment center. Downtown has more than 150,000 workers employed by 3,500 businesses. Major employers include Chevron, JPMorgan Chase, and Shell Oil. Living within a few blocks from work can shorten a lengthy commute to a quick, daily stroll. 3. No yard work. Easy maintenance. More amenities. Tired of mowing the lawn, trimming the trees or keeping up the exterior of a house? Loft & condo residents have a much easier and maintenance free lifestyle. Many loft & condo buildings also have fitness rooms, rooftop decks, pools & more amenities. 4. Easy to “lock and leave” for people on the go. Do you travel a lot? Worried about leaving your residence while you’re out of town? Living in a highrise makes it easy. Many buildings have security, staff and secured access - giving peace of mind for frequent travelers. f ONE OF HOUSTON’S TOP RANKED REALTORS Paige Martin | 713-384-5177 | Broker Associate, Keller Williams Realty | [email protected] Paige Martin HoustonTexasRealtor Broker Associate, Keller Williams Realty 713-384-5177 Paige.M.Martin [email protected] HoustonPaige Downtown Lofts & Condo Map Legend 1. -

Canyon Partners Real Estate Acquires $45M Preferred Equity Position in Houston Multifamily Asset

Canyon Partners Real Estate Acquires $45M Preferred Equity Position in Houston Multifamily Asset LOS ANGELES, March 16, 2021 - Canyon Partners Real Estate LLC (“Canyon”) today announced the acquisition of a $45 million preferred equity position in Drewery Place, a newly-built multifamily tower in Houston, Texas. The Class-A apartment building is comprised of 357 residential units and 11,000 square feet of prime retail space. The project was developed in 2019 by Australian lifestyle developer Caydon Property Group. The transaction, which closed in February 2021, was facilitated by JLL Capital Markets. Drewery Place is conveniently located in Midtown and is directly across from McGowen Station on METRORail’s Red Line, which provides direct service to Downtown Houston and Texas Medical Center. The Property boasts 360-degree views of Downtown Houston and the surrounding city as well as luxury finishes and sought-after amenities, including a resort- style pool with swim-up bar, fitness center, pet park, sky lounge, and coworking spaces. Drewery Place was the Multifamily winner of the Houston Business Journal’s 2020 Landmark Awards which recognizes outstanding real estate projects in Houston. This acquisition brings Canyon’s real estate portfolio to approximately $6.1 billion of project capitalization. ### About Canyon Partners Real Estate LLC Founded in 1991, Canyon Partners Real Estate LLC® ("Canyon") is the real estate direct investing arm of Canyon Partners, LLC, a global alternative asset manager with over $26 billion in assets under management. Over the last ten years, Canyon has invested more than $5.5 billion of debt and equity capital across approximately 200 transactions capitalizing approximately $14.6 billion of real estate assets, focusing on debt, value add, and opportunistic strategies. -

Downtown Route 832-851-3362 299

Passenger Service Number The Woodlands Express - Downtown Route www.woodlandstransit.com 832-851-3362 299 WHITE OAK BAYOU NEAR NORTHSIDE IH-10 IH-10 299 UH/Downtown Station DOWNTOWN HOUSTON BUFFALO BAYOU Express Woodlands 299 The BUFFALO BAYOU FIRST WARD Commerce Franklin Milam Harris County Jury Assembly Congress Congress Louisiana 4 MIN Harris County Courts Preston Preston Station (N/S) SIXTH WARD Wortham Center Minute Maid EAST END 299 The Woodlands Express Woodlands 299 The 1 MIN Prairie Park Prairie Alley Theatre DOWNTOWN HOUSTON Jones 2 MIN Red METRORail 12 MIN Texas Hall Capitol METRORail Green METRORail Green Capitol Central Station Main 1 MIN Rusk METRORail Purple METRORail Purple Hobby Center Walker Walker 3 MIN Main St Square SB Houston City Hall McKinney 299 299 2 MIN 10 MIN Discovery Green Lamar Lamar IH-45 Main St Square NB US 59 / IH-69 George R. Brown George Bagby Dallas Convention Center Convention 1 MIN Polk Polk METRORail Red METRORail FOURTH WARD FOURTH Toyota Clay 2 MIN 10 MIN Center Bell Bell Bell Station N/S Leeland EADO DOWNTOWN HOUSTON Milam Louisiana Pease Pease DOWNTOWN HOUSTON Brazos Smith Caroline Austin La Branch Crawford Jackson Chenevert Hamilton Main 1 MIN Travis Fannin San Jacinto Jefferson 299 299 St. Joseph Pkwy St. Joseph Pkwy METRO Dowtown Transit Center 2 MIN Pierce IH-45 STOP LOCATIONS MAP LEGEND THIRD WARD AM Operations 299 The Woodlands Express Route (Route 299) Milam @ Congress Milam @ Prairie METRORail Red Line (Route 700) Milam @ Capitol METRORail Green Line (Route 800) Milam @ Walker New! Try the new mobile ticketing app! Milam @ Lamar METRORail Purple Line (Route 900) Other Transit Providers Search for The Woodlands Express Milam @ Polk in the App Store & Google Play. -

Joint Infrastructure Development Plan

JOINT INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2017 THEGOODMANCORP.COM JOINT INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Existing Conditions and Demographics...............................................................9 Chapter 2: Project Development........................................................................................17 Chapter 3: Joint Project Prioritization.................................................................................30 Chapter 4: Funding and Implementation Strategy..............................................................83 Appendix A.......................................................................................................................100 Appendix B.......................................................................................................................127 Appendix C.......................................................................................................................130 Appendix D.......................................................................................................................131 Appendix E.......................................................................................................................133 Appendix F........................................................................................................................149 THEGOODMANCORP.COM phase EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The -

Austin to Houston Passenger Rail Study

Austin to Houston Passenger Rail Study Final Report December 2011 Prepared by Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... i Background .................................................................................................................................. i Existing Conditions .......................................................................................................................ii Alternative Alignments Analysis ..................................................................................................ii Improvements and Investments ................................................................................................. iv Conclusions ................................................................................................................................. ix Section 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 1 Austin-to-Hempstead Corridor ................................................................................................... 7 Section 2: Existing Infrastructure and Operations ......................................................................... -

Professional Report

2.0 Economics, Demographics, Freight, and the Multimodal Transportation System – Conditions and Trends 2.1 Introduction Texas is the second most populated state in the nation and contains the nation’s largest highway network, has the largest interstate network, and has the second highest volume of traffic. Texas ports handle 19.1 percent of the nation’s total domestic and foreign maritime cargo. Additionally, Texas has the largest freight rail network in the country carrying 8 percent of all freight moved by rail. There are 29 urban transit providers in Texas that account for 3 percent of the nation’s urban transit ridership.5 Finally, two of the nation’s top 10 busiest commercial airports (Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport [DFW] [4] and George Bush Intercontinental Airport [IAH] [8]) are located in Texas.6 Population and interrelated economic activity drive demand for transportation facilities and services. This chapter identifies Texas’ existing and projected demographic and economic conditions, the existing multi-modal transportation system and the potential effects of population and economic growth on that system. The future transportation needs of Texas are projected to be greater than in past years while future funding sources and levels are uncertain. Environmental concerns related to transportation are becoming more prevalent and the planning process must evolve to address these concerns. These topics will be discussed in depth in Chapter 8. What makes Texas transportation unique? Texas is a large state that has a lot of roadway mileage. It takes 13 hours at the posted speed limits to cross the state at its widest point. -

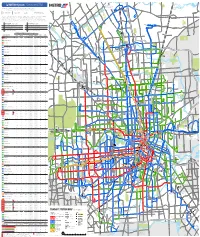

Download METRO System Map PDF

To Conroe P&R: 291 METRO System Sistema de METRO Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 W Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical To Kingwood P&R: Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. H 255, 259 CALI DR A Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: HOLLOW TREE LN R To Townsen P&R: Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y Las rutas están coloreadas segun la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. SPRING Medical 86 R F E M1 D 9 6 Center 86 99 P&R 0 E 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only 45 IM H ¨¦§ A P E R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales R D T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R E A D S L 99 T LE E Y R Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. B D SPUR 184 FM 1960 ELLA BLVD R LV D 1ST ST Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. S Lone Star T A U College L E D B I Rutas con dos colores (e.g. 15 / 30 minutos) tienen variaciones en frecuencia en diferentes segmentos como se muestra en el Mapa del N N 2)"49 E 86 99 D E R R K LOUETTA RD Y RD E RICHEY W Sistema.