Weathering the Snowstorm: Representing Northern Ontario By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2, 2012 Honourable Michael Chan Minister of Tourism, Culture & Sport 900 Bay Street, 9Th Floor, Hearst Block Toronto

April 2, 2012 Honourable Michael Chan Minister of Tourism, Culture & Sport 900 Bay Street, 9th Floor, Hearst Block Toronto, ON M7A 2E1 via email: [email protected] Dear Minister Chan: As President of the Northwestern Ontario Municipal Association, I am writing on behalf of our 37 member communities to express our extreme frustration regarding the announcement in Budget 2012 of the closure of the Kenora, Rainy River and Fort Frances Travel Centres. While we understand and support the need for deficit reduction, we question the rationale for closing every gateway centre in the western area of Northwestern Ontario. This decision will leave a busy tourist area completely void of the visitor information centres that are vital to providing visitors with the information they need to extend their stay and increase their spending – both of which are essential principles outlined within the Discovering Ontario report. It is interesting to note that the Fort Frances border crossing recorded a 10.8% increase in people crossing into Ontario this February. This decision comes on the heels of an earlier decision to reduce the funding to Municipally operated tourist information centres across the North. That resulted in fewer centres being available to assist the travelling public in learning what to see and where to go as they travel through this vast and magnificent land. 2 We encourage the Minister to delay the closure of the Fort Frances Visitor Centre until the requested meeting has been held between yourself, Mr. Ronald Holgerson of OTMPC, and the sub regional board members of Northern Ontario RTO 13 and Sunset Country and the North of Superior Travel Association. -

[email protected] / [email protected]

April 16, 2019 Honourable Peter Bethlenfalvy President of the Treasury Board Via email: [email protected] / [email protected] Honourable Greg Rickford Minister of Energy, Northern Development and Mines, and Indigenous Affairs Via email: [email protected] / [email protected] Dear Honourable Ministers: Ensuring Provincial procurement policies provide best value to regional communities. In order to directly engage the Provincial Government on policy issues of interest to our region, the Chambers of Commerce in Sudbury, Timmins, Sault Ste. Marie, North Bay and Thunder Bay wish to highlight our concerns around the Provincial Government’s recent announcement of a major initiative to consolidate and centralize procurement spending within Ontario Public Service and broader public sector agencies. Alternative Financing and Procurement (AFP), or public-private partnerships, are a highly viable option for risk sharing on major infrastructure projects and should remain a priority across Ontario. However, concerns expressed about the impacts to local small- and medium-sized businesses as a result of a centralized purchasing model are of significant concern to Northern communities. We are advocating against a centralized Greater Toronto Area (GTA) model as we believe that regionalized procurement efforts can deliver similar cost savings, while retaining, and controlling public spending within a region. We strongly believe that a GTA based buying model puts Northern businesses at a disadvantage and impedes the ability to build capacity throughout the province. To provide a regional example, the Lakehead Purchasing Consortium in Thunder Bay has a local award track-record in the 90 percent range, successfully demonstrating support for regional businesses while attaining cost savings through spend consolidation. -

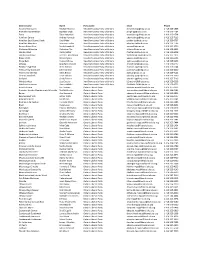

District Name

District name Name Party name Email Phone Algoma-Manitoulin Michael Mantha New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1938 Bramalea-Gore-Malton Jagmeet Singh New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1784 Essex Taras Natyshak New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0714 Hamilton Centre Andrea Horwath New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-7116 Hamilton East-Stoney Creek Paul Miller New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0707 Hamilton Mountain Monique Taylor New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1796 Kenora-Rainy River Sarah Campbell New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2750 Kitchener-Waterloo Catherine Fife New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6913 London West Peggy Sattler New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-6908 London-Fanshawe Teresa J. Armstrong New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-1872 Niagara Falls Wayne Gates New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 212-6102 Nickel Belt France GŽlinas New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-9203 Oshawa Jennifer K. French New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0117 Parkdale-High Park Cheri DiNovo New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-0244 Timiskaming-Cochrane John Vanthof New Democratic Party of Ontario [email protected] 1 416 325-2000 Timmins-James Bay Gilles Bisson -

Submission by the Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Institute of Canada (HRAI) to the Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs

August 20, 2020 Submission by the Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Institute of Canada (HRAI) to the Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs Re: Impacts on Small and Medium Enterprises Study of recommendations relating to the Economic and Fiscal Update Act, 2020 and the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on certain sectors of the economy COMMITTEE MEMBERS Amarjot Sandhu, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Brampton West (Chair) Jeremy Roberts, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Ottawa West—Nepean (Vice-Chair) Ian Arthur, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Kingston and the Islands Stan Cho, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Willowdale Stephen Crawford, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Oakville Mitzie Hunter, Ontario Liberal Party, Scarborough-Guildwood Sol Mamakwa, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Kiiwetinoong David Piccini, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Northumberland-Peterborough South Mike Schreiner, Green Party of Ontario, Guelph Sandy Shaw, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Hamilton West-Ancaster—Dundas Donna Skelly, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Flamborough-Glanbrook Dave Smith, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Peterborough-Kawartha Stephen Blais, Ontario Liberal Party, Orléans (non-voting) Catherine Fife, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Waterloo (non-voting) Randy Hillier, Independent, Lanark-Frontenac-Kingston (non-voting) Andrea Khanjin, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Barrie-Innisfil (non-voting) Laura Mae Lindo, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Kitchener Centre (non-voting) Kaleed Rasheed, Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, Mississauga East-Cooksville (non-voting) John Vanthof, New Democratic Party of Ontario, Timiskaming-Cochrane (non-voting) Committee Clerk: Julia Douglas cc Hon. Prabmeet Sarkaria, Minister of Small Business and Red Tape Reduction Hon. Monte McNaughton, Minister of Labour, Training and Skills Development Hon. -

Ontario Members of Provincial Parliament

Ontario Members of Provincial Parliament Government Office Constituency Office Government Office Constituency Office Sophia Aggelonitis, Parliamentary Assistant to the Laura Albanese, Parliamentary Assistant to the Minister of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Minister of Culture Hamilton Mountain, Liberal York South-Weston, Liberal Ministry of Small Business and Unit 2 - 952 Concession St Ministry of Culture Unit 102 - 2301 Keele St Entrepreneurship Hamilton ON L8V 1G2 900 Bay Street, 4th Floor, Toronto ON M6M 3Z9 1309 - 99 Wellesley St W, 1st Tel : 905-388-9734 Mowat Block Tel : 416-243-7984 Flr, Whitney Block Fax : 905-388-7862 Toronto ON M7A 1L2 Fax : 416-243-0327 Toronto ON M7A 1W2 saggelonitis.mpp.co Tel : 416-325-1800 [email protected] Tel : 416-314-7882 @liberal.ola.org Fax : 416-325-1802 Fax : 416-314-7906 [email protected] [email protected] Ted Arnott Wayne Arthurs, Parliamentary Assistant to the Wellington-Halton Hills, Progressive Conservative Minister of Finance Rm 420, Main Legislative 181 St. Andrew St E, 2nd Flr Pickering-Scarborough East, Liberal Building Fergus ON N1M 1P9 Ministry of Finance 13 - 300 Kingston Rd Toronto ON M7A 1A8 Tel : 519-787-5247 7 Queen's Park Cres, 7th Flr, Pickering ON L1V 6Z9 Tel : 416-325-3880 Fax : 519-787-5249 Frost Bldg South Tel : 905-509-0336 Fax : 416-325-6649 Toll Free : 1-800-265-2366 Toronto ON M7A 1Y7 Fax : 905-509-0334 [email protected] [email protected] Tel : 416-325-3581 Toll-Free: 1-800-669-4788 Fax : 416-325-3453 [email protected] -

Town of Bracebridge Council Correspondence

{GIXD1\ Town of Bracebridge ~ BRACEBRIDGE Council Correspondence The Heart of Muskoka TO: Mayor G. Smith and Members of Town Council J. Sisson, Chief Administrative Officer COPY: Management Team Media FROM: L. McDonald, Director of Corporate Services/Clerk DATE: June 24, 2020 CIRCULATION: Item # Description SECTION “A” – STAFF INFORMATION MEMOS: A1 Nil. SECTION “B” – GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE: Correspondence from Diane Kennedy, Director, and Paul Sisson, President, Muskoka Pioneer B1 Power Association, dated March 5, 2020, regarding Former Bracebridge Retired Firefighters Association Building and Property at J.D. Lang Activity Park. Correspondence from Christopher Abram, Chair, Board of Directors, St. John Ambulance – B2 Barrie-Simcoe-Muskoka Branch, dated June 15, 2020 regarding Proclaiming St. John Ambulance Week – June 21-27th, 2020. Resolution from Cheryl Mortimer, Clerk, Township of Muskoka Lakes, dated June 15, 2020, B3 regarding High Speed Internet Connectivity in Rural Ontario. Resolution from Carrie Sykes, Director of Corporate Services/Clerk, Township of Lake of Bays, B4 dated June 17, 2020, regarding High Speed Internet Connectivity in Rural Ontario. Resolution from Carrie Sykes, Director of Corporate Services/Clerk, Township of Lake of Bays, B5 dated June 17, 2020, regarding Basic Income for Income Security during COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Resolution from Jerri-Lynn Levitt, Deputy Clerk, Council and Legislative Services, Municipality B6 of Grey Highlands, dated June 18, 2020, regarding Universal Basic Income. Resolution from Jeanne Harfield, Clerk, Municipality of Mississippi Mills, dated June 19, 2020, B7 regarding Support for Rural Broadband. Correspondence from Todd Coles, City Clerk, City of Vaughan, dated June 22, 2020, B8 regarding The Establishment of a Municipal Financial Assistance Program to Offset the Financial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. -

FOCA Supports the Xplornet Fibre Proposal for Central And

Via email to [email protected] August 18, 2020 Hon. Laurie Scott Minister of Infrastructure 5th Floor, 777 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario M7A 2J3 Dear Minister Scott, On behalf of Ontario’s rural and northern waterfront property owners (WPO) we are writing in support of Xplornet’s proposal to the Improving Connectivity for Ontario (ICON) program regarding the company’s substantial broadband infrastructure project for central and northeastern Ontario. In 2018, FOCA undertook a research initiative, Waterfront Property Owners and Rural Economic Development ( https://foca.on.ca/waterfront-property-owners-and-rural-economic- development/ ); the study speaks to the opportunity of having WPO contribute to and support the local economy. It also confirmed the grim reality that access to reliable high-speed Internet is the number one barrier to a greater economic role of these families, many of whom are multi- generational residents who have significant interest and capacity to contribute to the economy in rural and northern communities. The study also helped to articulate the significance of waterfront property owners (WPO) as vital economic contributors to our rural communities. Xplornet’s project will build 2,650 km of new fibre across the province, adding 66 new wireless tower sites and 192 new wireless micro sites, most of which will be directly connected to the fibre network. Once completed, this project will enable over 170,000 residents across Ontario to enjoy affordable and accessible wireless services of 100 Megabits per second with unlimited data. The past months have demonstrated the importance of connectivity, especially for rural Canadians. The post-pandemic recovery offers the long overdue opportunity to provide the necessary tools for rural Canada’s success in the digital economy. -

GBHU BOH Motion 2019-21

May 6, 2019 The Honourable Christine Elliott Deputy Premier and Minister of Health and Long-Term Care College Park, 5th Floor 777 Bay Street Toronto ON M7A2J3 The Honourable Lisa MacLeod Minister of Children, Community and Social Services Hepburn Block, 6th Floor 80 Grosvenor Street Toronto ON M7A1E9 Re: Support for Bill 60 On April 26, 2019 at a regular meeting of the Board for the Grey Bruce Health Unit, the Board considered the attached correspondence from Peterborough Public Health urging the passing of Bill 60 as an important step towards fiscal responsibility and to address health inequalities. The following motion was passed: GBHU BOH Motion 2019-21 Moved by: Anne Eadie Seconded by: Sue Paterson “THAT, the Board of Health support the correspondence from Peterborough Public Health urging the passing of Bill 60” Carried Sincerely, Mitch Twolan Chair, Board of Health Grey Bruce Health Unit Encl. Cc: The Honourable Doug Ford, Premier of Ontario Local MP’s and MPP’s Association of Local Public Health Agencies Ontario Boards of Health Working together for a healthier future for all.. 101 17th Street East, Owen Sound, Ontario N4K 0A5 www.publichealthgreybruce.on.ca 519-376-9420 1-800-263-3456 Fax 519-376-0605 BOH - CORRESPONDENCE - 17 Jackson Square, 185 King Street, Peterborough, ON K9J 2R8 P: 705-743-1000 or 1-877-743-0101 F: 705-743-2897 peterboroughpublichealth.ca Serving the residents of Curve Lake and Hiawatha First Nations, and the County and City of Peterborough Serving the residents of Curve Lake and Hiawatha First Nations, and -

Historic Ruling 1885 Favours 2003 the Métis MNO President Lipinski Pleased with Decision

IssueISSUE No.N O78,. 75, M IDWINTERSPRING 2013 2013 Manitoba Métis Federation v. Canada Historic ruling 1885 favours 2003 the Métis MNO President Lipinski pleased with decision he lobby of the Supreme Court and rights amid concern of encroaching Louisof Canada building in Ottawa Canadian settlement. was crackling with excitement The federal government, however, dis- as Métis from across the home- tributed the land through a random lottery; land gathered there the morning as a result the Métis became a landless of March 8, 2013, to learn the aboriginal people, with few Métis receiving Supreme Court of Canada deci- what they had been promised. Tsion concerning Manitoba Metis Feder- When the case finally reached the ation v. Canada (the “MMF case”). Supreme Court in December 2011, the The MMF case represented over 140 Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) obtained years of Canadian history and Métis had intervener status in order to offerDay its support — Continued on page 10 waited a long time for its resolution. It and to ensure that the voice of Ontario had gone through almost Métis was heard in this every legal& hurdle POW imagi- LEY ANNIVERSARYimportant case. The MNO EVENTS nable andRiel taken over 30 “After our long hunt was represented at the years to reach the Supreme for justice in the Supreme Court by Jean Court. The case was based Teillet, the Métis lawyer 2013 landmark Powley on the claim that Canada case, we knew it was who, 10 years earlier, rep- breached its fiduciary and important for us resented Steve Powley at constitutional obligations the Supreme Court and owing to the Manitoba to be here at the who is the great niece of Métis by failing to fulfill Supreme Court.” Louis Riel. -

COMMITTEE of the WHOLE MINUTES 7:00 PM November 8, 2005 Council Chambers

COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE MINUTES 7:00 PM November 8, 2005 Council Chambers CALL TO ORDER The meeting was called to order at 7:03 PM with roll call as follows: Mayor D McArthur Council B Hiller L Huard M Richardson Absent P C Halonen Staff L Cresswell, Clerk/Deputy Treasurer M Bottomley, Treasurer/Deputy Clerk C Mayry, Executive Assistant K Pristanski, Township Superintendent APPROVAL OF AGENDA Additions: Communications 16. Ministry of the Environment – Pam Cowie, Drinking Water Inspector - Invitation to attend MOE/Northern Municipalities’ Meeting Unfinished Business 4. Schreiber Diesels Hockey Club Update 5. Township Christmas Social Deletions: Delegations John Redins, Heritage Days Committee DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST - None DELEGATIONS - None REPORTS 1. Superintendent Report – Received It was noted that there have been a number of false alarms at the Medical Centre in the past week which will be examined by the security service provider. The fourth item under Water in the report should read “Order #1 is in the works and #2 is an Order to OCWA and will be complete by November 15, 2005.” A memo from the Ontario Building Officials Association regarding the Ontario Association of Architects and Professional Engineers of Ontario lobbying the province for an exemption for testing on building code requirements was discussed. Recommended that Council forward a letter to the Honourable John Gerretsen, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, indicating its support for the OBOA position in not granting an exemption to the Ontario Association of Architects and Professional Engineers of Ontario for testing on building code requirements, and that a copy of the letter be sent to Michael Gravelle, M.P.P. -

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014

Ontario Government Quick Reference Guide: Key Officials and Opposition Critics August 2014 Ministry Minister Chief of Staff Parliamentary Assistant Deputy Minister PC Critic NDP Critic Hon. David Aboriginal Affairs Milton Chan Vic Dhillon David de Launay Norm Miller Sarah Campbell Zimmer Agriculture, Food & Rural Affairs Hon. Jeff Leal Chad Walsh Arthur Potts Deb Stark Toby Barrett N/A Hon. Lorenzo Berardinetti; Sylvia Jones (AG); Jagmeet Singh (AG); Attorney General / Minister responsible Shane Madeleine Marie-France Lalonde Patrick Monahan Gila Martow France Gélinas for Francophone Affairs Gonzalves Meilleur (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) (Francophone Affairs) Granville Anderson; Alexander Bezzina (CYS); Jim McDonell (CYS); Monique Taylor (CYS); Children & Youth Services / Minister Hon. Tracy Omar Reza Harinder Malhi Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Laurie Scott (Women’s Sarah Campbell responsible for Women’s Issues MacCharles (Women’s Issues) (Women’s Issues) Issues) (Women’s Issues) Monte Kwinter; Cristina Citizenship, Immigration & International Hon. Michael Christine Innes Martins (Citizenship & Chisanga Puta-Chekwe Monte McNaughton Teresa Armstrong Trade Chan Immigration) Cindy Forster (MCSS) Hon. Helena Community & Social Services Kristen Munro Soo Wong Marguerite Rappolt Bill Walker Cheri DiNovo (LGBTQ Jaczek Issues) Matthew Torigian (Community Community Safety & Correctional Hon. Yasir Brian Teefy Safety); Rich Nicholls (CSCS); Bas Balkissoon Lisa Gretzky Services / Government House Leader Naqvi (GHLO – TBD) Stephen Rhodes (Correctional Steve Clark (GHLO) Services) Hon. David Michael Government & Consumer Services Chris Ballard Wendy Tilford Randy Pettapiece Jagmeet Singh Orazietti Simpson Marie-France Lalonde Wayne Gates; Economic Development, Employment & Hon. Brad (Economic Melanie Wright Giles Gherson Ted Arnott Percy Hatfield Infrastructure Duguid Development); Peter (Infrastructure) Milczyn (Infrastructure) Hon. Liz Education Howie Bender Grant Crack George Zegarac Garfield Dunlop Peter Tabuns Sandals Hon. -

Liberal Privatization of Hydroone Will Not Work For

NEWS RELEASE Liberal Privatization of HydroONE Will Not Work Communiqué for Northern Ontario John Vanthof April 20, 2015 MPP/Deputé Timiskaming -Cochrane Last Thursday, Premier Kathleen Wynne announced that the Liberal Government plans to sell the Hydro ONE distribution system to help pay New Liskeard Office/Bureau 247 Whitewood Ave., Box 398 for her Government’s transit construction plans. The announcement was Pinewoods Centre, Unit 5 intentionally made outside of the Legislature during Question Period, New Liskeard, ON P0J 1P0 which is the period of time set aside for Opposition MPPs to hold the Phone: (705) 647-5995 Government to account on behalf of the people of Ontario. Rather than Toll Free: 1-888-701-1105 take responsibility for their plan of action, Premier Wynne and her inner Fax: (705) 647-1976 cabinet simply decided not to show up to Question Period. In protest of the Email/Courriel: Government’s disrespectful behavior, the NDP caucus loudly demanded [email protected] answers on HydroONE, to the point that all NDP members were ejected Kirkland Lake Office/Bureau from the House. We took this strong action to bring attention to the pitfalls 30 Second Street East of the Premier’s misguided decision to sell HydroONE, and her disregard 2nd Floor, East Wing for Ontarians. Kirkland Lake, ON P2N 3H7 Phone: (705) 567-4650 High electricity rates are one of the biggest issues facing Northern Ontario Toll Free: 1-800-461-2186 residents and businesses. Here in the North, the majority of our energy Fax: (705) 567-4208 Email/Courriel: comes from publically-owned Ontario Power Generation (OPG) hydro- [email protected] electric dams, which generate sustainable, low-cost energy.