In Nanumba South, Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Consociational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016) Halidu Musah

Democratic Governance and Conflict Resistance in Conflict-prone Societies : A Consociational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016) Halidu Musah To cite this version: Halidu Musah. Democratic Governance and Conflict Resistance in Conflict-prone Societies : A Conso- ciational Analysis of the Experiences of Ghana in West Africa (1992-2016). Political science. Université de Bordeaux, 2018. English. NNT : 2018BORD0411. tel-03092255 HAL Id: tel-03092255 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03092255 Submitted on 2 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX THÈSE PRÉSENTÉE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR EN SCIENCE POLITIQUE DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE BORDEAUX École Doctorale SP2 : Sociétés, Politique, Santé Publique SCIENCES PO BORDEAUX Laboratoire d’accueil : Les Afriques dans le monde (LAM) Par: Halidu MUSAH TITRE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE AND CONFLICT RESISTANCE IN CONFLICT-PRONE SOCIETIES: A CONSOCIATIONAL ANALYSIS OF THE EXPERIENCES OF GHANA IN WEST AFRICA (1992-2016) (Gouvernance démocratique et résistance aux conflits dans les sociétés enclines aux conflits: Une analyse consociationnelle des expériences du Ghana en Afrique de l'Ouest (1992-2016)). Sous la direction de M. Dominique DARBON Présentée et soutenue publiquement Le 13 décembre 2018 Composition du jury : M. -

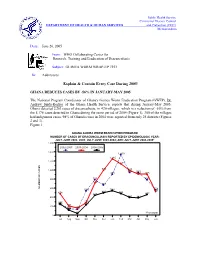

Explain & Contain Every Case During 2005!

Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES and Prevention (CDC) Memorandum Date: June 20, 2005 From: WHO Collaborating Center for Research, Training and Eradication of Dracunculiasis Subject: GUINEA WORM WRAP-UP #153 To: Addressees Explain & Contain Every Case During 2005! GHANA REDUCES CASES BY -56% IN JANUARY-MAY 2005 The National Program Coordinator of Ghana's Guinea Worm Eradication Program (GWEP), Dr. Andrew_Seidu-Korkor of the Ghana Health Service, reports that during January-May 2005, Ghana detected 2,263 cases of dracunculiasis, in 420 villages, which is a reduction of -56% from the 5,176 cases detected in Ghana during the same period of 2004 (Figure 1). 300 of the villages had indigenous cases. 98% of Ghana's cases in 2004 were reported from only 25 districts (Figures 2 and 3). Figure 1 GHANA GUINEA WORM ERADICATION PROGRAM NUMBER OF CASES OF DRACUNCULIASIS REPORTED BY EPIDEMIOLOGIC YEAR: JULY-JUNE 2002- 2003; JULY-JUNE 2003-2004; AND JULY-JUNE 2004-2005* 1,600 2002-2003 2003-2004 2004-2005 1,400 1,339 1,245 1,200 1,133 996 990 1,000 944 940 903 907 905 800 785 785 712 665 NUMBER OF CASES 600 558 539 544 520 474 496 482 439 457 400 393 387 257 278 234 230 203 200 142 158 115 131 38 *Provisional 0 Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Two districts, Nkwanta (Volta Region) and Tolon-Kumbungu (Northern Region), that together reported 35% of Ghana's cases in 2004, have recorded reductions of -90% (from 1,006 to 97 cases) and -11% (from 452 to 404 cases), respectively, in cases during Jan. -

Establishing an Index Insurance Trigger for Crop Loss in Northern Ghana

ESTABLISHLISING AN IINDEXNDEX INSURANCE TRIGGERS FOR CROP LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA The Katie School of Insurance RESEARCH P A P E R N o . 7 SEPTEMBER 2011 ESTABLISHING AN INDEX of income for 60 percent of the population. INSURANCE TRIGGER FOR CROP Agricultural production depends on a number of LOSS IN NORTHERN GHANA factors including economic, political, technological, as well as factors such as disease, fires, and certainly THE KATIE SCHOOL OF weather. Rainfall and temperature have a significant INSURANCE 1 effect on agriculture, especially crops. Although every part of the world has its own weather patterns, and managing the risks associated with these patterns has ABSTRACT always been a part of life as a farmer, recent changes As a consequence of climate change, agriculture in in weather cycles resulting from increasing climate many parts of the world has become a riskier business change have increased the risk profile for farming and activity. Given the dependence on agriculture in adversely affected the ability of farmers to get loans. developing countries, this increased risk has a Farmers in developing countries may respond to losses potentially dramatic effect on the lives of people in ways that affect their future livelihoods such as throughout the developing world especially as it selling off valuable assets, or removing their children relates to their financial inclusion and sustainable from school and hiring them out to others for work. access to capital. This study analyzes the relationships They may also be unable to pay back loans in a timely between rainfall per crop gestation period (planting – manner, which makes rural banks and even harvesting) and crop yields and study the likelihood of microfinance institutions reluctant to provide them with crop yield losses. -

Nanumba North District Assembly

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2014 FISCAL YEAR Contents SECTION I: ASSEMBLY’S COMPOSITE BUDGET STATEMENT The District Assembly …................................................................................... 1 Location And Size ............................................................................................ 1 Topography and Drainage................................................................................. 2 Climate and Vegetation .................................................................................... 3 Human Settlement ……………............................................................................. 3 Demographic Characteristics ……….................................................................... 4 Economic Activity and Poverty……………………….................................................. 4 Strategic Direction, 2014-2016 ………………………………......................................... 5 Status of Implementation of Budget 2012 and 2013 …………………...................... 6 Summary of 2012 and 2013 Budget ………......................................................... 7 Achievements 2013 ………………………………………………........................................ 8 Challenges and Constraints ………………………………..…………………....................... 8 Budget 2014 ………………………………………......................................................... 10 Assumptions Underlying Budget Formulation…………......................................... 10 Revenue Improvement Strategies for 2014 …………………………......................... -

Nanumba North District Assembly Bimbilla

NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY BIMBILLA MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2014-2017) (BASED ON GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENDA-GSGDA II) PREPARED BY: DISTRICT PLANNINIG COORDINATION UNIT BIMBILLA NOVEMBER 2013 10 | P a g e NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT (2014 - 2017 MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN) ACRONYMS AC AREA COUNCIL AEA AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AGENT AIDS ACQUIRED IMMUNED DEFICIENCY SYNDROME ART ANTI RETROVIRAL THERAPY CAPS COMMUNITY ACTION PLANS CBRDP COMMUNITY BASED RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT CCBT COMMUNITY CAPACITY BUILDING TEAM CHPS COMMUNITY HEALTH PLANNING SERVICES CRS CATHOLIC RELIEF SERVICES CSIR COUNCIL FOR SCIENTIFIC AND INDUSTRIAL RESEARCH CWSA COMMUNITY WATER AND SANITATION AGENCY DA DISTRICT ASSEMBLY DADU DISTRICT AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT UNIT DCE DISTRICT CHIEF EXECUTIVE DDF DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT FACILITY DFR DEPARTMENT OF FEEDER ROADS DHMT DISTRICT HEALTH MANAGEMENT TEAM DMTDP DISTRICT MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN DPCU DISTRICT PLANNING CO-ORDINATING UNIT DWAP DISTRICT WIDE ASSISTANCE PROJECT EHU ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH UNIT EU EUROPEAN UNION 11 | P a g e NANUMBA NORTH DISTRICT (2014 - 2017 MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN) GDO GENDER DESK OFFICER GES GHANA EDUCATION SERVICE GSGDA GHANA SHARED GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT AGENDA GOG GOVERNMENT OF GHANA GPRS II GROWTH AND POVERTY REDUCTION STRATEGY HIV HUMAN IMMUNED VIRUS JHS JUNIOJR HIGH SCHOOL KVIP KUMASI VENTILATED IMPROVED PIT LI LEGISLATIVE INSTRUMENT M&E MONITORING AND EVALUATION MOE MINISTRY OF ENERGY MOFA MINISTRY OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE MTDP MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN NDPC -

District Profile

KPANDAI DISTRICT PROFILE 1.2.1 Introduction This section examines the geophysical characteristics of the District including the demography, culture, the district economy, social services, vulnerability as well as HIV/AIDs and gender, nature and status of the built environment as well as the current situation in relation to the seven pillars of the Medium-Term Development Policy Framework. 1.2.3 Geophysical Characteristics 1.2.3.1 Location and size The District can be located at the South-Eastern corner of the Northern Region of Ghana and lies between latitudes 8º N and 9.29º N and longitudes 0.29 º E and 1.26ºW. It is bordered to the North by Nanumba South District, East Gonja to the West, Krachi West District to the South-West, Nkwanta North District to the East and Pru District in Brong Ahafo Region to the South The District has a total surface area of 1,772.04sqkm with water covering about 5%. The District is strategically located – the central point between the Northern part and Southern part of the Eastern corridor of Ghana. The District can therefore take advantage of its strategic location to be a gateway to both the Southern and Northern Ghana. Similarly, strategic facilities of national importance aimed at wider coverage for both the southern and northern Ghana can be conveniently located in the district to achieve the desired results. Being strategically located in the transitional zone, the district has the advantage of experiencing mixed climatic conditions that have both positive and adverse implications for the district‟s development. -

The Leap to Literacy and Life Change in Northern Ghana

The Leap to Literacy and Life Change in Northern Ghana An Impact Assessment of School for Life (SfL) Final Report (Abridged Version) By Dr Leslie Casely-Hayford and Adom Baisie Ghartey (External Consultants) and The SfL Internal Impact Assessment Team September, 2007 1 Acknowledgements This study is dedicated to Philip Natuk Bilikuni, the Saboba District Supervisor who died in a motor accident in the process of the Impact Assessment (IA). Philip was a very committed educationist and served with SfL for several years. The contents of this report are based on a joint effort between the external consultants and the SfL staff who conducted the IA over a one year period in order to review SfL’s impact over the last 12 years. The report has required extensive time and effort by the School for Life staff in all aspects of data collection and analysis. It has benefited greatly from the guidance and support of the Internal School for Life Impact Assessment Team who include : Mr Sulemana Osman Saaka, Programme Director; Mr Hussein Abdul.Ziblim, Deputy Director, Operations; Ms Helene Horsbrugh, Programme Development Advisor; and Mr A. A. Huseini, Principal Educationist. The Field Teams for the IA Tracer Study included the following people: Name Designation Location or Field Team institution Hussein A. Ziblim Deputy Director, Operations Head office Team 1 Dramani Isaac Imoro District Coordinator East Gonja Team 1 Natuk Bilikuni Philip District Supervisor Saboba/Chereponi Team 1 Hussein Muhib District Supervisor Gushegu/Karaga Team 1 Esther Samuel -

Table of Contents Part A: Strategic Overview

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART A: STRATEGIC OVERVIEW ................................................................................ 3 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE DISTRICT .................................................................... 3 2. VISION ..................................................................................................................... 4 3. MISSION .................................................................................................................. 5 4. GOALS ..................................................................................................................... 5 5. CORE FUNCTIONS ................................................................................................. 6 6. DISTRICT ECONOMY .............................................................................................. 8 7. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2020 ............................................................................. 10 8. REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE .............................................. 18 a. REVENUE .............................................................................................................. 18 b. EXPENDITURE ...................................................................................................... 19 9. NMTDPF OBJECTIVES IN LINE WITH SDGS AND TARGETS AND COAST ..... 22 10. POLICY OUTCOME INDICATORS AND TARGETS .......................................... 23 PART B: BUDGET PROGRAMME/SUB-PROGRAMME SUMMARY ......................... 26 PROGRAMME 1: MANAGEMENT AND -

Nanumba South District Assembly Page 1 the COMPOSITE BUDGET

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE NANUMBA SOUTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2013 FISCAL YEAR Nanumba South District Assembly Page 1 For Copies of this MMDA’s Composite Budget, please contact the address below: The Coordinating Director, Nanumba South District Assembly Northern Region This 2013 Composite Budget is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh or www.ghanadistricts.com TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I: ASSEMBLY’S COMPOSITE BUDGET STATEMENT INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND 6 Our Vision ................................................................................................................................. 6 Our Mission ............................................................................................................................... 6 Population size and growth rate ............................................................................................ 6 Age and Sex Composition....................................................................................................... 7 STRUCTURE OF THE DISTRICT ECONOMY 8 Agriculture ................................................................................................................................ 8 Roads and Transport ............................................................................................................... 9 Electricity and Power ............................................................................................................. 10 Water Infrastructure ............................................................................................................ -

Divination and Health

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh READING THE MIND OF THE SPIRITS: DIVINATION AND HEALTH- SEEKING BEHAVIOUR AMONG THE DAGOMBA IN THE NORTHERN REGION OF GHANA SALIFU ABUKARI (10174411) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN SOCIOLOGY. NOVEMBER, 2017 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I, SALIFU ABUKARI, hereby declare that this thesis is my own work from a study carried out in the Northern Region of Ghana. This thesis was written under the supervision of my supervisors, Professors Kodjo Senah, Steve Tonah and Philip Baba Adongo. As far as I am aware, this thesis has not been submitted in part or in whole to any university for the award of any degree or certificate. ……………………………………. ……………………….. SALIFU ABUKARI DATE (CANDIDATE) SUPERVISORS ………………………………….. ……..………………………….. PROFESSOR KODJO SENAH PROFESSOR STEVE TONAH (PRINCIPAL SUPERVISOR) (SUPERVISOR) DATE……………………. DATE……………… …………………………………………. PROFESSOR PHILIP BABA ADONGO (SUPERVISOR) DATE……………………………… i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT Finding explanation for the causes of ill-health and other misfortunes has been and continues to agitate the human mind. Among the Dagomba of the Northern Region of Ghana, consulting diviners for virtually every situation, good or bad, makes diviners ’critical actors in the health-seeking behaviour of the people. This study explored the significance of divination in the health-seeking behaviour among the Dagomba. Specifically, the study was guided by the following objectives: (i) To describe the practice of divination and how it affects health decision-making; (ii) To examine reasons why a sick Dagomba will shop for the services of both a diviner and an orthodox medical practitioner; (iii)To examine gender relations and its consequences in the practices of divination; and (iv) To describe the circumstances under which divination is employed. -

The Land Factor in the Konkomba- Nanumba Crisis of 1981 a Historical Perspective

The Land Factor in the Konkomba- Nanumba Crisis Of 1981 A Historical Perspective Cliff S. Maasole Dept. of Social, Political and Historical Studies University for Development Studies Wa, Ghana Email: [email protected] doi:10.4314/gjds.v8i1.3 Abstract In post-independent Ghana, over twenty ethnic conflicts have erupted in Northern Ghana. These conflicts can however be traced as far back to colonial land policies and treatments of ethnic interests of that part of Ghana. The Konkomba, in particular, have been involved in many such conflicts, largely over land and related resource. The period between the 1980s and 1990s were particularly tumultuous due the many inter-ethnic conflicts and armed confrontations. This paper examines one of such conflicts, which occurred in 1981 between theK onkomba and the Nanumba, both of the Northern Region of Ghana. It focuses on the historical antecedents of the war from pre-colonial to date to demonstrate how land has been a key issue. The analysis is informed by the results of an in-depth study that relied on secondary sources, archival materials and oral interviews. The study found that underneath the seemly cordial relations that had existed between the Konkomba and Nanumba in Nanun11prior to 1981 were tensions over territorial claims and land rights. It explains how mis-interpretation of ownership created the conditions for the war. It dwells in particular on the Alhassan Committee Report of 1978 and its role in inflaming the sentiments resulting in the violent outburst of 1981. Key Words: Identity, Ethnic Conflicts, Territorial Claims, Land Policies, Ownership 11 Refers to the Nanumba Traditional Area GJDS, Vol. -

The Effects of the Gonja-Nawuri Conflict on Inter-Ethnic Relations in Kpandai

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES THE EFFECTS OF THE GONJA-NAWURI CONFLICT ON INTER- ETHNIC RELATIONS IN KPANDAI DISTRICT MACLEAN NINSAW GBATI DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE JULY, 2017 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES THE EFFECTS OF THE GONJA-NAWURI CONFLICT ON INTER- ETHNIC RELATIONS IN KPANDAI DISTRICT BY MACLEAN NINSAW GBATI (ID. NO. 10083706) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE AWARD OF DEGREE OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE JULY, 2017 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I MACLEAN NINSAW GBATI, therefore declare that apart from the references that was made from other literatures which were duly acknowledged, the thesis is my personal original research work which has not been researched by any person for the award of partial or full degree elsewhere. …………………………. MACLEAN NINSAW GBATI Student ID: 10083706 DATE:……………………………. ……………………………… … ……………………………… DR. SEIDU MAHAMA ALIDU DR. ZIBLIM IDDI Principal Supervisor Co-Supervisor DATE:…………………………… DATE: …………………………………… i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT Inter-ethnic conflicts have flared up intermittently in Ghana, especially in the northern part of the country, which has a large number of different ethnic communities. These conflicts have left damaging implications for socio-economic development, but also for inter-ethnic relations. This study sought to analyse the Gonja-Nawuri conflict of 1991-1992 in Kpandai in the Northern region. The objective was to establish the impact of the conflict on inter-ethnic relations.