Ladon =-.R/: Oblique Case Marker 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist

DHARMA KINGS AND FLYING WOMEN: BUDDHIST EPISTEMOLOGIES IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY INDIAN AND BRITISH WRITING by CYNTHIA BETH DRAKE B.A., University of California at Berkeley, 1984 M.A.T., Oregon State University, 1992 M.A. Georgetown University, 1999 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2017 This thesis entitled: Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing written by Cynthia Beth Drake has been approved for the Department of English ________________________________________ Dr. Laura Winkiel __________________________________________ Dr. Janice Ho Date ________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Drake, Cynthia Beth (Ph.D., English) Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing Thesis directed by Associate Professor Laura Winkiel The British fascination with Buddhism and India’s Buddhist roots gave birth to an epistemological framework combining non-dual awareness, compassion, and liberational praxis in early twentieth-century Indian and British writing. Four writers—E.M. Forster, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Lama Yongden, and P.L. Travers—chart a transnational cartography that mark points of location in the flow and emergence of this epistemological framework. To Forster, non- duality is a terrifying rupture and an echo of not merely gross mismanagement, but gross misunderstanding by the British of India and its spiritual legacy. -

Educating the Heart

Approaching Tibetan Studies About Tibet Geography of Tibet Geographical Tibet Names: Bod (Tibetan name) Historical Tibet (refers to the larger, pre-1959 Tibet, see heavy black line marked on Tibet: A Political Map) Tibet Autonomous Region or Political Tibet (refers to the portion of Tibet named by People’s Republic of China in 1965, see bolded broken line on Tibet: A Political Map) Khawachen (literary Tibetan name meaning “Abode of Snows”) Xizang (the historical Chinese name for meaning “Western Treasure House”) Land of Snows (Western term) Capital: Lhasa Provinces: U-Tsang (Central & Southern Tibet) Kham (Eastern Tibet) Amdo (Northeastern Tibet) Since the Chinese occupation of Tibet, most of the Tibetan Provinces of Amdo and Kham have been absorbed into the Chinese provinces of Qinghai, Sichuan, and Yunnan Main Towns: Llasa, Shigatse, Gyantse, Chamdo Area: 2,200,000 Sq. kilometers/850,000 sq. miles Elevation: Average 12-15,000 feet Tibet is located on a large plateau called the Tibetan Plateau. Borders: India, Nepal, Bhutan, Burma (south) China (west, north, east) Major Mountains Himalaya (range to south & west) and Ranges Kunlun (range to north) Chomolungma (Mt. Everest) 29,028 ft. Highest peak in the world Kailas (sacred mountain in western Tibet to Buddhists, Hindus & Jains) The Tibetan Plateau is surrounded by some of the world’s highest mountain ranges. Major Rivers: Ma Chu (Huzng He/Yellow Dri Chu (Yangtze) Za Chu (Mekong) Ngul Chu (Salween) Tsangpo (Bramaputra) Ganges Sutlej Indus Almost all of the major rivers in Asia have their source in Tibet. Therefore, the ecology of Tibet directly impacts the ecology of East, Southeast and South Asia. -

English Versions of Chinese Authors' Names in Biomedical Journals

Dialogue English Versions of Chinese Authors’ Names in Biomedical Journals: Observations and Recommendations The English language is widely used inter- In English transliteration, two-syllable Forms of Chinese Authors’ Names nationally for academic purposes. Most of given names sometimes are spelled as two in Biomedical Journals the world’s leading life-science journals are words (Jian Hua), sometimes as one word We recently reviewed forms of Chinese published in English. A growing number (Jianhua), and sometimes hyphenated authors’ names accompanying English- of Chinese biomedical journals publish (Jian-Hua). language articles or abstracts in various abstracts or full papers in this language. Occasionally Chinese surnames are Chinese and Western biomedical journals. We have studied how Chinese authors’ two syllables (for example, Ou-Yang, Mu- We found considerable inconsistency even names are presented in English in bio- Rong, Si-Ma, and Si-Tu). Editors who are within the same journal or issue. The forms medical journals. There is considerable relatively unfamiliar with Chinese names were in the following categories: inconsistency. This inconsistency causes may mistake these compound surnames for • Surname in all capital letters followed by confusion, for example, in distinguishing given names. hyphenated or closed-up given name, for surnames from given names and thus cit- China has 56 ethnic groups. Names example, ing names properly in reference lists. of minority group members can differ KE Zhi-Yong (Chinese Journal of In the current article we begin by pre- considerably from those of Hans, who Contemporary Pediatrics) senting as background some features of constitute most of the Chinese population. GUO Liang-Qian (Chinese Chinese names. -

The Supposed Tibetan Or Nepalese Name of Mt. Everest. 127

The Supposed Tibetan or Nepalese Name of Mt. Everest. 127 THE SUPPOSED TIBETAN OR NEPALESE NAME OF MouNT EvEREST. 1 ROM time to time, and more especially perhaps in continental mountaineering literature, one notices the use of the word Chomo-lungma, as if it were the true and accepted Tibetan name of Mount Everest. And for this usage there is perhaps some reason, since the name is .written across the Mount Everest massif on the map accomp anying The Fight for Everest (1924), and it also app ears in the form Chomo Longmo on t he -!-inch sheet, 'Mount Everest and Environs,' publish ed by the Survey of India in 1930, as well as on the map accomp anying Everest, 1933. Now it will be remembered that during the reconnaissance of Mount Everest in 1921 Lt.-Col. Howard Bury reported that the name Ohomo-lungma was applied by Tibetans to both Everest and its great neighbour Makalu, but that locally Chomo Uri was also used for the former peak. lVIoreover, in Nepal a number of years earlier General Bruce had heard the name Ohomo Lungmo applied to Mount Everest by Sherpa Bhutias.1 Other native names pre viously suggested, though without adequate foundation, have been Chholungbu and Chomo Kankar, the latter having been favoured by Douglas Freshfield.2 And it is perhaps needless to mention the misidentification of Gaurisankar with Everest by Schlagintweit in 1855. This has led to frequent use of the former name on German and other atlases, in spite of repeated official and other representa tions since the d ays when Capt. -

Discussion Guide About This Guide

Discussion Guide About this Guide This guide is designed to be used in conjunction with the filmValley of the Heroes. It contains background information about the film and its subject matter, discussion questions, and additional resources. It has been written with classroom and community settings in mind, but can be used by anybody who would like to facilitate a screening and discussion about the film. Table of Contents Filmmaker Statement 3 Context for the Film 4 Disambiguation: What is Tibet? 5 Geography 6 A Brief History of Hualong (Dpa’Lung) 7 Qinghai Nationalities University Local Education Aid Group (LEAG) 8 Discussion Questions and Activities 9 Recommended Resources 10 Right Turning Conch Shell - a Tibetan auspicious Film Purchase Information 11 symbol associated with heroism. 2 Filmmaker Statement by Khashem Gyal “When no one listens, no one tells, and when no one tells, no one learns, and thus when the elders die, so do the traditions and language.” This old Tibetan proverb sadly captures the current situation of Tibetan oral (LEAG). In my first class, I started teaching a Tibetan subject, and realized that traditions and language. Each year sees the passing of precious aged people, and three quarters of the students were unable to understand Tibetan at all. The other there is a decline in the number of children who speak Tibetan and understand teachers and I had collected Tibetan folklore, riddles, songs, and dance to teach their culture. to the students. They were interested, but much of the time we had to explain in Chinese. Tibetan civilization is characterized by a very strong oral and popular culture, combined with a sophisticated intellectual, religious, and philosophical literary We wanted to have a good relationship with the community, so we decided to visit production. -

SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

The 14th International Seminar on Sea Names Geography, Sea Names, and Undersea Feature Names The sense of names Geographical names as dynamic element of a world in motion Isolde Hausner (Chair, Austrian Committee on Geographical Names) 1. Introduction : Toponyms as cultural and historical heritage – names and identity from a linguistic perspective: A speech community denominates the objects of its surrounding natural and cultural area with its specific names inventary which exercises a cognitive function in communication, this means that names have a community building function in society. The function of toponyms and the motives of naming are primarily focused on the natural and cultural surroundings of a society and their achievements on the cultivation of their living space. With the toponyms people create a spatial identity, they feel familiar with the region and in this sense toponyms are part of the cultural and historical heritage of a region. If there are alterations – is it the object itself or any other changes from outside (e.g. natural hazards, political, social alterations) – name changes can and will happen, names can newly be created but names can also disappear. Toponyms have furthermore the function to be a historical and linguistic documentation of a region, because they store information on the natural space and the socio-cultural developments in the course of the centuries. In this context I mention also the name protection on the national and international level. Countries have their own laws and rules to protect their geographical names, and have the right to denominate objects on their territory. The United Nations group of experts on geographical names (UNGEGN) coordinates all these endeavours of the member states and sets standards for the implementation in practice. -

Common Ground Between Islam and Buddhism

Common Ground Between Islam and Buddhism Common Ground Between Islam and Buddhism By Reza Shah-Kazemi With an essay by Shaykh Hamza Yusuf Introduced by H. H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama H. R. H. Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad Professor Mohammad Hashim Kamali First published in 2010 by Fons Vitae 49 Mockingbird Valley Drive Louisville, KY 40207 http://www.fonsvitae.com Email: [email protected] © Copyright The Royal Aal-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, Jordan 2010 Library of Congress Control Number: 2010925171 ISBN 978–1891785627 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior permission of the publishers. All rights reserved. With gratitude to the Thesaurus Islamicus Foundation for the use of the fourteenth century Qur’ānic shamsiyya lotus image found in Splendours of Qur’ān Calligraphy and Illumination by Martin Lings. We also thank Justin Majzub for his artistic rendition of this beautiful motif. Printed in Canada iv Contents Foreword by H. H. the Fourteenth Dalai Lama vii Introduction by H. R. H. Prince Ghazi bin Muhammad ix Preface by Professor Mohammad Hashim Kamali xvii Acknowledgements xxii Common Ground Between Islam and Buddhism Part One — Setting the Scene 1 Beyond the Letter to the Spirit 1 A Glance at History 7 Qur’ānic Premises of Dialogue 12 The Buddha as Messenger 14 Revelation from on High or Within? 19 The Dalai Lama and the Dynamics of Dialogue 24 Part Two — Oneness: The Highest Common Denominator 29 Conceiving of the One 29 The Unborn 30 Buddhist Dialectics 33 Shūnya and Shahāda 40 Light of Transcendence -

The Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship and The

BY BENJAMIN H. SNYDER Haverford College A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Anthropology at Bryn Mawr College. May 2003 Bismillahir-Rahmanir-Rahim In the name of God, Most Merciful, Most Compassionate ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 REFLECTIONS ON COMMUNITY AND SPIRITUALITY METHODS CHAPTER 1: BAWA AND THE GENERATIONS 18 THE FOUNDING OF THE FELLOWSHIP THE FIRST GENERATION AND THE EARLY YEARS THE SECOND GENERATION AND THE LATER YEARS CONCLUSIONS CHAPTER 2: TRADITIONALISM, MODERNISM, AND THE PATH 47 LEARNING UNITY, LIVING UNITY FORGING A MIDDLE WAY A RELIGION FOR THE MODERN AGE CONCLUSIONS CHAPTER 3: THE POND AND FELLOWSHIP CULTURE 68 WHY THE FELLOWSHIP WAS CREATED PROBLEMS AND SPIRITUAL MATERIALISM A CULTURE OF UNITY EXPRESSING FELLOWSHIP CULTURE CONCLUSIONS CONCLUSION 86 ENTERING HEARTSPACE APPENDIX: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE 97 GLOSSARY 98 BIBLIOGRAPHY 99 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS THERE ARE NOT ENOUGH thank yous in my body to express my gratitude to everyone at the Fellowship who took time out of their days to talk to me, who took an interest in my life, and who generally made me feel more welcome than I have ever felt. This project is by you and for you. I can only take credit for writing it down. Thank you for opening my eyes to the importance of unconditional friendship and having a melting heart. If I have made any mistakes, please forgive me. Thank you also to Professor Takenaka for being a patient and challenging advisor and to everyone else in the Bryn Mawr Anthropology Department for supporting a four- year habit of being nosey. -

The Tibetan Image of Confucius

The Tibetan Image of Confucius By Shen-yu Lin ong tse ’phrul gyi rgyal po is a visible figure which frequently Kappears in the Tibetan texts for the gTo-rituals. Kong tse ’phrul gyi rgyal po, a name generally found both in the literature of the Bonpo and Buddhist traditions, is regarded as the innovator of the gTo-rituals, which are performed to solve various problems of daily life. This kind of ritual, though popular among the Tibetan common folk, is customarily not open to strangers. While its framework resembles the “Stage of Generation” (bskyed rim) of trantric practices, the core of the ritual is proven to be related to sorcery.1 During recitation, the ritual master talks to the spirits or the negative forces which are considered to be the sources of misfortune and thus should be exorcised. Kong tse ’phrul gyi rgyal po is often referred to as an authoritative personage in this ritual whom the evil beings should regard with reverence and awe.2 Using threat or persuasion, the ritual master forces the spirit to leave so that the victim is freed from troubles. Kong tse ’phrul gyi rgyal po is regarded as one who possesses magical power and his role in the gTo-rituals reinforces the magical effect of the ritual itself. The gTo-ritual is conducted by the skillful simultaneous implementation of several favora- ble conditions, creating an atmosphere which induces magical healing. The magical healing powers generated by invoking Kong tse ’phrul gyi rgyal po is consistent with the meaning of this epithet ’phrul gyi rgyal po, which is usually interpreted as “the king of magic”. -

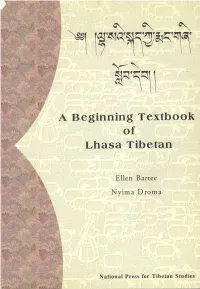

Tibetan, a Beginning Textbook of Lhasa

A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan C\ C\ C\ -y^ A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan Ellen Bartee Nyima Droma National Press for Tibetan Studies 2000 Cataloging in Publication Data Bartee, Ellen Nyima Droma A Beginning Textbook of Lhasa Tibetan Edited by Nganwan Pincuo, designed by Li Jianxiong Includes glossary 1. Language, Tibetan, Elementary 2. Linguistics, Tibeto-Burman ISBN 7-80057-430-X/G.19 First printed in 1999 by the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Revised version reprinted in 2000 by National Press for Tibetan studies. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, except for personal use. CONTENTS Preface... vii Lesson One The Tibetan alphabet 9 Lesson Two Prefixes and suffixes 13 Lesson Three Superscribed and subjoined letters 17 Lesson Four What is this? 23 Lesson Five What nationality are you? 31 Lesson Six Where are you from? 37 Lesson Seven Tell me about yourself and your family 45 Lesson Eight Where are you going? What do you do? 55 honorifics and ^5] Q5) Lesson Nine What time is it? 67 NO Lesson Ten Eating and drinking 79 Lesson Eleven Everyday activities 89 Lesson Twelve Making plans and setting a date 95 review of verbs and ^1/^ Lesson Thirteen Going to Lhasa 105 |C |^ l*|q| ^ Lesson Fourteen What are you doing? 115 Tl <W §c ^c *H and the ergative marker ^ Lesson Fifteen Arriving in Lhasa 129 v Lesson Sixteen Tibetan tea 139 3*1 R^ ^ Lesson Seventeen Visiting a doctor 147 ~S \3 NO Lesson Eighteen At the store , 155 adjective forms (^ ^^ 5 $), comparative marker ^^ and the question particle ^^ Appendix I: Answers for practice work . -

Table of Contents Notes for Salman Rushdie: the Satanic Verses Paul

Notes for Salman Rushdie: The Satanic Verses Paul Brians Professor of English, Washington State University [email protected] Version of February 13, 2004 For more about Salman Rushdie and other South Asian writers, see Paul Brians’ Modern South Asian Literature in English . Table of Contents Introduction 2 List of Principal Characters 8 Chapter I: The Angel Gibreel 10 Chapter II: Mahound 30 Chapter III: Ellowen Deeowen 36 Chapter IV: Ayesha 45 Chapter V: A City Visible but Unseen 49 Chapter VI: Return to Jahilia 66 Chapter VII: The Angel Azraeel 71 Chapter VIII: 81 Chapter IX: The Wonderful Lamp 84 The Unity of The Satanic Verses 87 Selected Sources 90 1 fundamental religious beliefs is intolerable. In the Western European tradition, novels are viewed very differently. Following the devastatingly successful assaults of the Eighteenth Century Enlightenment upon Christianity, intellectuals in the West largely abandoned the Christian framework as an explanatory world view. Indeed, religion became for many the enemy: the suppressor of free thought, the enemy of science This study guide was prepared to help people read and study and progress. When the freethinking Thomas Jefferson ran for Salman Rushdie’s novel. It contains explanations for many of its President of the young United States his opponents accused him allusions and non-English words and phrases and aims as well of intending to suppress Christianity and arrest its adherents. at providing a thorough explication of the novel which will help Although liberal and even politically radical forms of Christianity the interested reader but not substitute for a reading of the book (the Catholic Worker movement, liberation theology) were to itself. -

Liu Manqing : a Sino-Tibetan Adventurer and the Origin of a New Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the 1930S Fabienne Jagou

Liu Manqing : A Sino-Tibetan Adventurer and the Origin of a New Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the 1930s Fabienne Jagou To cite this version: Fabienne Jagou. Liu Manqing : A Sino-Tibetan Adventurer and the Origin of a New Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the 1930s. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, CNRS, 2009, Ancient Currents, New Traditions: Papers Presented at the Fourth International Seminar of Young Tibetologists, 17, pp.5-20. hal- 02557150 HAL Id: hal-02557150 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02557150 Submitted on 28 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Liu Manqing: A Sino-Tibetan Adventurer and the Origin of a New Sino-Tibetan Dialogue in the 1930s Fabienne Jagou1 Member of the École française d’Extrême-Orient he young lady who departed from Nanjing to Lhasa in 1929 against the will of her family and who endured the hardship of a year’s T travel through the gorges of Khams and the snowy mountains peaks of Tibet is known by her Chinese name: Liu Manqing (1906-1941). A few decades ago, parents used to tell their children her story, and Liu Manqing’s name is still on their minds many years later.