Volume 3 | January 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lntertextuality in AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights

lNTERTEXTUALITY IN AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights Edited by Drew Eisenhauer and Brenda Murphy McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London Table of Contents Introduction: What Is "'ntertextuality" and Why Is the Term Important Today? DREW EISENHAUER .......................... 1 Part I: Literary Intertextuality LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA SECTION ONE: PoETS Intertextuality in American drama : critical essays on Eugene O'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, Arthur Miller The Ancient Mariner and O'Neill's Intertextual Epiphany and other playwrights I edited by Drew Eisenhauer and (Herman Daniel Farrell III) ............................... 10 Brenda Murphy. p. em. "Deep in my silent sea": Eugene O'Neill's Extended Includes bibliographical references and index. Adaptation of Coleridge's The Ancient Mariner ISBN 978-0-7864-6391-6 (Rupendra Guha Majumdar) ............................... 25 softcover : acid free paper § A Multi-Faceted Moon: Shakespearean and Keatsian Echoes 1. American drama- 20th century- History in Eugene O'Neill's A Moon for the Misbegotten and criticism. 2. O'Neill, Eugene, 1888-1953- (Aurelie Sanchez) ........................................ 36 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Glaspell, Susan, 1876-1948- Criticism and interpretation. Trailing Clouds of Glory: Glaspell, Romantic Ideology 4. Wilder, Thornton, 1897-1975- Criticism and Cultural Conflict in Modern American Literature and interpretation. 5. Miller, Arthur, 1915-2005- Criticism and interpretation. 6. Intertextuality. (Michael Winetsky) ...................................... 52 I. Eisenhauer, Drew. II. Murphy, Brenda, 1950- On Closets and Graves: Intertextualities in Susan Glaspell's PS350.I58 2013 Alison's House and Emily Dickinson's Poetry 812'.509-dc23 2012038662 (Noelia Hernando-Real) ................................. -

OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May

Click Here for More Articles on 2017 AWARDS SEASON OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May. 7, 2017 Tweet Share The Lortel Awards were presented May 7, 2017 at NYU Skirball Center beginning at 7:00 PM EST. This year's event was hosted by actor and comedian, Taran Killam, and once again served as a benefit for The Actors Fund. Leading the nominations this year with 7 each are the new musical, Hadestown - a folk opera produced by New York Theatre Workshop - and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, currently at the Barrow Street Theatre, which has been converted into a pie shop for the intimate staging. In the category of plays, both Paula Vogel's Indecent and J.T. Rogers' Oslo, current Broadway transfers, earned a total of 4 nominations, including for Outstanding Play. Playwrights Horizons' A Life also earned 4 total nominations, including for star David Hyde Pierce and director Anne Kauffman, earning her 4th career Lortel Award nomination; as did MCC Theater's YEN, including one for recent Academy Award nominee Lucas Hedges for Outstanding Lead Actor. Lighting Designer Ben Stanton earned a nomination for the fifth consecutive year - and his seventh career nomination, including a win in 2011 - for his work on YEN. Check below for live updates from the ceremony. Winners will be marked: **Winner** Outstanding Play Indecent Produced by Vineyard Theatre in association with La Jolla Playhouse and Yale Repertory Theatre Written by Paula Vogel, Created by Paula Vogel & Rebecca Taichman Oslo **Winner** Produced by Lincoln Center Theater Written by J.T. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

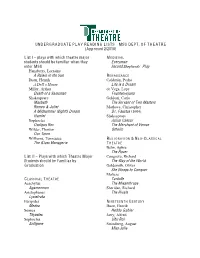

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Our-Town-Study-Guide.Pdf

STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PERFORMANCE INFORMATION PAGE 3 TORNTON WILDER PAGE 4 THORNTON WILDER CHRONOLOGY PAGE 5 OUR TOWN: A BRIEF HISTORY PAGE 6 PLAY SYNOPSIS PAGE 7 CAST OF CHARACTERS PAGE 10 THE PULITZER PRIZE PAGE 11 OUR TOWN: A HISTORICAL TIMELINE PAGE 12 THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGING PAGE 16 THEMES OF OUR TOWN PAGE 17 NEW HAMPSHIRE PAGE 18 SCENIC DESIGN PAGE 19 PROMPTS FOR DISCUSSION PAGE 21 AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE PAGE 22 STUDENT EVALUATION PAGE 23 TEACHER EVALUATION PAGE 24 New Stage Theatre Presents OUR TOWN by Thornton Wilder Directed by Francine Thomas Reynolds Sponsored by Sanderson Farms Stage Manager Lighting Designer Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Brent Lefavor Dex Edwards Costume Designer Technical Director/Properties Lesley Raybon Richard Lawrence There will be one 10-minute intermission THE CAST Cast (in order of appearance) STAGE MANAGER Sharon Miles DR. GIBBS Larry Wells HOWIE NEWSOME Christan McLaurine JOE CROWELL, JR. Ben Sanders MRS. GIBBS Malaika Quarterman MRS. WEBB Kerri Sanders GEORGE GIBBS Cliff Miller * REBECCA GIBBS Mary Frances Dean WALLY WEBB Jeffrey Cornelius EMILY WEBB Devon Caraway* PROFESSOR WILLARD Amanda Dear MR. WEBB Yohance Myles* WOMAN #1 LaSharron Purvis SIMON STIMSON Jeff Raab WOMAN #2 Hope Prybylski WOMAN #3 Ashanti Alexander CONSTABLE WARREN Chris Roebuck MRS. SOAMES Joy Amerson SI CROWELL Alex Forbes SAM CRAIG Jake Bell JOE STODDARD James Anderson FARMER MCCARTY Peter James VIOLINIST Miranda Kunk *The actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Profes- sional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. THORNTON WILDER Thornton Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin on April 17, 1897. -

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Southern Comfort

FROM THE NATIONAL ALLIANCE FOR MUSICAL THEAtre’s PresideNT Welcome to our 24th Annual Festival of New Musicals! The Festival is one of the highlights of the NAMT year, bringing together 600+ industry professionals for two days of intense focus on new musical theatre works and the remarkably talented writing teams who create them. This year we are particularly excited not only about the quality, but also about the diversity—in theme, style, period, place and people—represented across the eight shows that were selected from over 150 submissions. We’re visiting 17th-century England and early 20th century New York. We’re spending some time in the world of fairy tales—but not in ways you ever have before. We’re visiting Indiana and Georgia and the world of reality TV. Regardless of setting or stage of development, every one of these shows brings something new—something thought-provoking, funny, poignant or uplifting—to the musical theatre field. This Festival is about helping these shows and writers find their futures. Beyond the Festival, NAMT is active year-round in supporting members in their efforts to develop new works. This year’s Songwriters Showcase features excerpts from just a few of the many shows under development (many with collaboration across multiple members!) to salute the amazing, extraordinarily dedicated, innovative work our members do. A final and heartfelt thank you: our sponsors and donors make this Festival, and all of NAMT’s work, possible. We tremendously appreciate your support! Many thanks, too, to the Festival Committee, NAMT staff and all of you, our audience. -

Bach at Leipzig

43rd Season • 411th Production JULIANNE ARGYROS STAGE / SEPTEMBER 24 - OCTOBER 15, 2006 David Emmes Martin Benson PRODUCING ARTISTIC DIRECTOR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR presents BACH AT LEIPZIG by Itamar Moses Thomas Buderwitz Maggie Morgan Geoff Korf SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN Tom Cavnar Darin Anthony Martin Noyes SOUND DESIGN ASSISTANT DIRECTOR FIGHT DIRECTOR Megan Monaghan Jeff Gifford Erin Nelson* DRAMATURG PRODUCTION MANAGER STAGE MANAGER DIRECTED BY Art Manke Bach at Leipzig • SOUTH COAST REPERTORY P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Johann Friedrich Fasch ......................................................... Stephen Caffrey* Georg Balthasar Schott ...................................................... Tony Abatemarco* Georg Lenck ..................................................................... Jeffrey Hutchinson* Johann Martin Steindorff .......................................................... Erik Sorensen* Georg Friedrich Kaufmann ............................................... John-David Keller* Johann Christoph Graupner ............................................. Timothy Landfield* The Greatest Organist in Germany .................................... Sean H. Hemeon* SETTING The narthex of St. Thomas Lutheran Church, Leipzig, Germany, 1722. Later, 1750. LENGTH Approximately two hours and 20 minutes, including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting .............................................................................. Joanne DeNaut Production Assistant .............................................................. -

History of Towson University's MFA in Theatre Arts Program

Towson University: College of Fine Arts and Communication M.F.A. in Theatre Arts History of Towson University’s M.F.A. in Theatre Arts Program The MFA Program in Theatre Arts at Towson University started in 1994 under the leadership of Juanita Rockwell. In its 20‐year history, the program has engaged in a number of ambitious projects (originated by both students and faculty), presented over 60 theatre projects and performance pieces and received a number of outside accolades for these endeavors. Students and alumni have worked with a variety of professional artists and have also gone on to create theatre companies of their own. They have also taught at a number of colleges and universities, and have embarked on successful professional careers at institutions around the country. Tours MFA productions have toured to international festivals in Bulgaria, Slovakia, Egypt, Poland and Hungary. National tours of shows have included trips to Boston, New York City, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Chicago, and Austin, Texas. In the summer of 2009, a group of MFA students did a Study Abroad Program to Wroclaw, Poland. There they attended the Grotowski Institute’s festival, “The World as a Place of Truth,” a celebration of the life and work of the famous Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski. The students also participated in a five‐day, six‐hours‐a‐day workshop with Teatr ZAR, the in‐house theatre company at the Grotowski Institute. In the summer of 2011, the program presented a showcase at the ToRoNaDa Space in New York City. The two‐week showcase, entitled Modicums, includes The Natasha Plays; Return to Sender by Shannon McPhee; The Title Sounded Better in French by Lola B. -

Mactheatre Theatre Departme

Think You Need A BFA? ................................................................................................................... 3 Is a BFA Degree Part of the Recipe for Musical Theater Success? ................................................. 7 A Little Quiz ................................................................................................................................... 12 Broadway's Big 10: Top Colleges Currently Represented on Currently Running Shows .............. 14 Monthly College Planning Guide For Visual & Performing Arts Students. ................................... 18 Theatre and Musical Theatre College Audition Timeline in a Nutshell ........................................ 48 Gain An Edge Over The Summer ................................................................................................... 50 6 Keys To Choosing The Perfect College For The Arts. ................................................................. 53 The National Association for College Admission Counseling Performing and Visual Arts Fairs in Houston & Dallas. ......................................................................................................................... 55 Unifieds ......................................................................................................................................... 58 TX Thespian Festival College Auditions......................................................................................... 68 Theatre College-Bound Resource Index. ..................................................................................... -

10+ Tickets [email protected]

Ali Stroker won the 2019 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical for her role as ‘Ado Annie’ in Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma! She made history as the first actor in a wheelchair to appear on Broadway in Deaf West’s acclaimed 2015 revival of Spring Awakening. Stroker starred in 12 episodes of the talent competition, The Glee Project, winning a guest role on Fox’s Glee. She recurred in the Kyra Sedgwick ABC series, Ten Days in the Valley and guest starred on Freeform's The Bold Type, Fox’s Lethal Weapon, CBS’ Instinct, The CW's Charmed and Comedy Central's Drunk History. She’s performed her cabaret act at Green Room 42 and solo’ed at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC, New York’s Town Hall, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts and Carnegie Hall. Stroker is an honorary board member of The National Disability Theatre. Her mission to improve the lives of others through the arts, disabled or not, is captured in her motto: “Turning Your Limitations Into Your Opportunities.” Price per location Table seating Theater seating 10+ TICKETS SINGLE TICKETS [email protected] Per ticket cost listed. To order less than 10 tickets, please call 412-456-6666. NO REFUNDS OR EXCHANGES. Dates, times, locations and prices subject to change without notice. Groups do not need to sit together or in the same price range, they need only to attend the same performance. Best available seating. Per order handling fee applied to all group sale orders ($6.00 phone and $10.00 online). -

South Coast Repertory Is a Professional Resident Theatre Founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson

IN BRIEF FOUNDING South Coast Repertory is a professional resident theatre founded in 1964 by David Emmes and Martin Benson. VISION Creating the finest theatre in America. LEADERSHIP SCR is led by Artistic Director David Ivers and Managing Director Paula Tomei. Its 33-member Board of Trustees is made up of community leaders from business, civic and arts backgrounds. In addition, hundreds of volunteers assist the theatre in reaching its goals, and about 2,000 individuals and businesses contribute each year to SCR’s annual and endowment funds. MISSION South Coast Repertory was founded in the belief that theatre is an art form with a unique power to illuminate the human experience. We commit ourselves to exploring urgent human and social issues of our time, and to merging literature, design, and performance in ways that test the bounds of theatre’s artistic possibilities. We undertake to advance the art of theatre in the service of our community, and aim to extend that service through educational, intercultural, and community engagement programs that harmonize with our artistic mission. FACILITY/ The David Emmes/Martin Benson Theatre Center is a three-theatre complex. Prior to the pandemic, there were six SEASON annual productions on the 507-seat Segerstrom Stage, four on the 336-seat Julianne Argyros Stage, with numerous workshops and theatre conservatory performances held in the 94-seat Nicholas Studio. In addition, the three-play family series, “Theatre for Young Audiences,” produced on the Julianne Argyros Stage. The 20-21 season includes two virtual offerings and a new outdoors initiative, OUTSIDE SCR, which will feature two productions in rotating rep at the Mission San Juan Capistrano in July 2021.