The Lived Experiences of Our Community: Stories & Data From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lntertextuality in AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights

lNTERTEXTUALITY IN AMERICAN DRAMA Critical Essays on Eugene 0 'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, -~Arthur Miller and Other Playwrights Edited by Drew Eisenhauer and Brenda Murphy McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London Table of Contents Introduction: What Is "'ntertextuality" and Why Is the Term Important Today? DREW EISENHAUER .......................... 1 Part I: Literary Intertextuality LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA SECTION ONE: PoETS Intertextuality in American drama : critical essays on Eugene O'Neill, Susan Glaspell, Thornton Wilder, Arthur Miller The Ancient Mariner and O'Neill's Intertextual Epiphany and other playwrights I edited by Drew Eisenhauer and (Herman Daniel Farrell III) ............................... 10 Brenda Murphy. p. em. "Deep in my silent sea": Eugene O'Neill's Extended Includes bibliographical references and index. Adaptation of Coleridge's The Ancient Mariner ISBN 978-0-7864-6391-6 (Rupendra Guha Majumdar) ............................... 25 softcover : acid free paper § A Multi-Faceted Moon: Shakespearean and Keatsian Echoes 1. American drama- 20th century- History in Eugene O'Neill's A Moon for the Misbegotten and criticism. 2. O'Neill, Eugene, 1888-1953- (Aurelie Sanchez) ........................................ 36 Criticism and interpretation. 3. Glaspell, Susan, 1876-1948- Criticism and interpretation. Trailing Clouds of Glory: Glaspell, Romantic Ideology 4. Wilder, Thornton, 1897-1975- Criticism and Cultural Conflict in Modern American Literature and interpretation. 5. Miller, Arthur, 1915-2005- Criticism and interpretation. 6. Intertextuality. (Michael Winetsky) ...................................... 52 I. Eisenhauer, Drew. II. Murphy, Brenda, 1950- On Closets and Graves: Intertextualities in Susan Glaspell's PS350.I58 2013 Alison's House and Emily Dickinson's Poetry 812'.509-dc23 2012038662 (Noelia Hernando-Real) ................................. -

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

Undergraduate Play Reading List

UND E R G R A DU A T E PL A Y R E A DIN G L ISTS ± MSU D EPT. O F T H E A T R E (Approved 2/2010) List I ± plays with which theatre major M E DI E V A L students should be familiar when they Everyman enter MSU Second 6KHSKHUGV¶ Play Hansberry, Lorraine A Raisin in the Sun R E N A ISSA N C E Ibsen, Henrik Calderón, Pedro $'ROO¶V+RXVH Life is a Dream Miller, Arthur de Vega, Lope Death of a Salesman Fuenteovejuna Shakespeare Goldoni, Carlo Macbeth The Servant of Two Masters Romeo & Juliet Marlowe, Christopher A Midsummer Night's Dream Dr. Faustus (1604) Hamlet Shakespeare Sophocles Julius Caesar Oedipus Rex The Merchant of Venice Wilder, Thorton Othello Our Town Williams, Tennessee R EST O R A T I O N & N E O-C L ASSI C A L The Glass Menagerie T H E A T R E Behn, Aphra The Rover List II ± Plays with which Theatre Major Congreve, Richard Students should be Familiar by The Way of the World G raduation Goldsmith, Oliver She Stoops to Conquer Moliere C L ASSI C A L T H E A T R E Tartuffe Aeschylus The Misanthrope Agamemnon Sheridan, Richard Aristophanes The Rivals Lysistrata Euripides NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y Medea Ibsen, Henrik Seneca Hedda Gabler Thyestes Jarry, Alfred Sophocles Ubu Roi Antigone Strindberg, August Miss Julie NIN E T E E N T H C E N T UR Y (C O N T.) Sartre, Jean Shaw, George Bernard No Exit Pygmalion Major Barbara 20T H C E N T UR Y ± M ID C E N T UR Y 0UV:DUUHQ¶V3rofession Albee, Edward Stone, John Augustus The Zoo Story Metamora :KR¶V$IUDLGRI9LUJLQLD:RROI" Beckett, Samuel E A R L Y 20T H C E N T UR Y Waiting for Godot Glaspell, Susan Endgame The Verge Genet Jean The Verge Treadwell, Sophie The Maids Machinal Ionesco, Eugene Chekhov, Anton The Bald Soprano The Cherry Orchard Miller, Arthur Coward, Noel The Crucible Blithe Spirit All My Sons Feydeau, Georges Williams, Tennessee A Flea in her Ear A Streetcar Named Desire Synge, J.M. -

Our-Town-Study-Guide.Pdf

STUDY GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS PERFORMANCE INFORMATION PAGE 3 TORNTON WILDER PAGE 4 THORNTON WILDER CHRONOLOGY PAGE 5 OUR TOWN: A BRIEF HISTORY PAGE 6 PLAY SYNOPSIS PAGE 7 CAST OF CHARACTERS PAGE 10 THE PULITZER PRIZE PAGE 11 OUR TOWN: A HISTORICAL TIMELINE PAGE 12 THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGING PAGE 16 THEMES OF OUR TOWN PAGE 17 NEW HAMPSHIRE PAGE 18 SCENIC DESIGN PAGE 19 PROMPTS FOR DISCUSSION PAGE 21 AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE PAGE 22 STUDENT EVALUATION PAGE 23 TEACHER EVALUATION PAGE 24 New Stage Theatre Presents OUR TOWN by Thornton Wilder Directed by Francine Thomas Reynolds Sponsored by Sanderson Farms Stage Manager Lighting Designer Scenic Designer Elise McDonald Brent Lefavor Dex Edwards Costume Designer Technical Director/Properties Lesley Raybon Richard Lawrence There will be one 10-minute intermission THE CAST Cast (in order of appearance) STAGE MANAGER Sharon Miles DR. GIBBS Larry Wells HOWIE NEWSOME Christan McLaurine JOE CROWELL, JR. Ben Sanders MRS. GIBBS Malaika Quarterman MRS. WEBB Kerri Sanders GEORGE GIBBS Cliff Miller * REBECCA GIBBS Mary Frances Dean WALLY WEBB Jeffrey Cornelius EMILY WEBB Devon Caraway* PROFESSOR WILLARD Amanda Dear MR. WEBB Yohance Myles* WOMAN #1 LaSharron Purvis SIMON STIMSON Jeff Raab WOMAN #2 Hope Prybylski WOMAN #3 Ashanti Alexander CONSTABLE WARREN Chris Roebuck MRS. SOAMES Joy Amerson SI CROWELL Alex Forbes SAM CRAIG Jake Bell JOE STODDARD James Anderson FARMER MCCARTY Peter James VIOLINIST Miranda Kunk *The actor appears through the courtesy of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Profes- sional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. THORNTON WILDER Thornton Wilder was born in Madison, Wisconsin on April 17, 1897. -

Plays to Read for Furman Theatre Arts Majors

1 PLAYS TO READ FOR FURMAN THEATRE ARTS MAJORS Aeschylus Agamemnon Greek 458 BCE Euripides Medea Greek 431 BCE Sophocles Oedipus Rex Greek 429 BCE Aristophanes Lysistrata Greek 411 BCE Terence The Brothers Roman 160 BCE Kan-ami Matsukaze Japanese c 1300 anonymous Everyman Medieval 1495 Wakefield master The Second Shepherds' Play Medieval c 1500 Shakespeare, William Hamlet Elizabethan 1599 Shakespeare, William Twelfth Night Elizabethan 1601 Marlowe, Christopher Doctor Faustus Jacobean 1604 Jonson, Ben Volpone Jacobean 1606 Webster, John The Duchess of Malfi Jacobean 1612 Calderon, Pedro Life is a Dream Spanish Golden Age 1635 Moliere Tartuffe French Neoclassicism 1664 Wycherley, William The Country Wife Restoration 1675 Racine, Jean Baptiste Phedra French Neoclassicism 1677 Centlivre, Susanna A Bold Stroke for a Wife English 18th century 1717 Goldoni, Carlo The Servant of Two Masters Italian 18th century 1753 Gogol, Nikolai The Inspector General Russian 1842 Ibsen, Henrik A Doll's House Modern 1879 Strindberg, August Miss Julie Modern 1888 Shaw, George Bernard Mrs. Warren's Profession Modern Irish 1893 Wilde, Oscar The Importance of Being Earnest Modern Irish 1895 Chekhov, Anton The Cherry Orchard Russian 1904 Pirandello, Luigi Six Characters in Search of an Author Italian 20th century 1921 Wilder, Thorton Our Town Modern 1938 Brecht, Bertolt Mother Courage and Her Children Epic Theatre 1939 Rodgers, Richard & Oscar Hammerstein Oklahoma! Musical 1943 Sartre, Jean-Paul No Exit Anti-realism 1944 Williams, Tennessee The Glass Menagerie Modern -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

Tisa Bryant, Author/Scholar

TISA BRYANT, AUTHOR/SCHOLAR Tisa Bryant, born in 1966 in Tucson, Arizona. Interviewed on March 13, 2005 by Ana-Maurine Lara As you know, this project is really about hearing your story. I would love to start with an earlier part of your life, asking you about some of the defining moments from before the age of 20 that have really influenced who you are. I’ll work in reverse chronological order. Moving out of my parents’ home, a couple of days after high school graduation to New York for a very, very short stint. I didn’t know you lived in New York. Yeah, it wasn’t to the New York that I envisioned `cause we ended up in Long Island, so it was very, very different and very black, actually. I didn’t realize. I hear `island’ in this country and it kind of means something different. But yeah, being 17 in the summer, moving into and ended up in Boston and we were in the second term of Ronald Reagan. It was at that moment of really having to confront the world. I waited to finally be free to make my own decisions about life and it was really bewildering to really try to understand the systems that comprised the world and what they actually meant to me. I always knew that there was a lot of power in the world that I didn’t have, but then the kinds of interactions and being completely broke and really young and working a job and living in an apartment with a whole bunch of crazy kids who were just completely transient, you know. -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

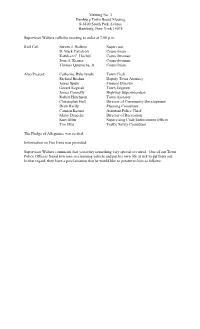

Meeting No. 3 Hamburg Town Board Meeting S-6100 South Park Avenue Hamburg, New York 14075

Meeting No. 3 Hamburg Town Board Meeting S-6100 South Park Avenue Hamburg, New York 14075 Supervisor Walters calls the meeting to order at 7:00 p.m. Roll Call: Steven J. Walters Supervisor D. Mark Cavalcoli Councilman Kathleen C. Hochul Councilwoman Joan A. Kesner Councilwoman Thomas Quatroche, Jr. Councilman Also Present: Catherine Rybczynski Town Clerk Richard Boehm Deputy Town Attorney James Spute Finance Director Gerard Kapsiak Town Engineer James Connolly Highway Superintendent Robert Hutchison Town Assessor Christopher Hull Director of Community Development Drew Reilly Planning Consultant Carmen Kesner Assistant Police Chief Marty Denecke Director of Recreation Kurt Allen Supervising Code Enforcement Officer Tim Ellis Traffic Safety Consultant The Pledge of Allegiance was recited. Information on Fire Exits was provided. Supervisor Walters comments that yesterday something very special occurred. One of our Town Police Officers found two men in a burning vehicle and put his own life at risk to get them out. In that regard, they have a proclamation that he would like to present to him as follows: Councilwoman Hochul comments that the Town was awarded by Sports Illustrated as a “Good Sports Community” finalist out of 1,300 communities that submitted nominations for this award. The Town of Hamburg came in the top seventeen and that is an incredible tribute to our Recreation Department and Mr. Denecke and his incredible team of professionals and Councilman Quatroche, who was the liaison up until this past January when she took over. 7:00 p.m. Public Hearing for an amendment to said Zoning Code for properties located at 4962 South Park Avenue; 4954 South Park Avenue; 4950 South Park Avenue; 4215 Howard Road and 4227 Howard Road and the contiguous water tank property to be rezoned from C-2 to NC. -

Preoccupations of Some Asian Australian Women's Fiction at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century

eTropic 16.2 (2017): ‘Bold Women Write Back’ Special Issue | 118 Preoccupations of Some Asian Australian Women’s Fiction at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carole Ferrier The University of Queensland Abstract This paper offers a look back over the rise of the visibility, and the rise as a category, of Asian Australian fiction from the beginning of the 1990s, and especially in the twenty-first century, and some of the main questions that have been asked of it by its producers, and its readers, critics, commentators and the awarders of prizes. It focuses upon women writers. The trope of “border crossings”—both actual and in the mind, was central in the late-twentieth century to much feminist, Marxist, postcolonial and race-cognisant cultural commentary and critique, and the concepts of hybridity, diaspora, whiteness, the exotic, postcolonising and (gendered) cultural identities were examined and deployed. In the “paranoid nation” of the twenty-first century, there is a new orientation on the part of governments towards ideas of—if not quite an imminent Yellow Peril—a “fortress Australia,” that turns back to where they came from all boats that are not cruise liners, containerships or warships (of allies). In the sphere of cultural critique, notions of a post-multiculturality that smugly declares that anything resembling identity politics is “so twentieth-century,” are challenged by a rising creative output in Australia of diverse literary representations of and by people with Asian connections and backgrounds. The paper discusses aspects of some works by many of the most prominent of these writers. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Mellon Library's 2017 Summer Reading Suggestions for Rising 6

Mellon Library’s 2017 th Summer Reading Suggestions for Rising 6 Graders RECENT FICTION Alexander, Kwame. Booked Twelve-year-old Nick is a football-mad boy who absolutely hates books. In this follow-up to the Newbery-winning novel The Crossover, football, family, love, and friendship take centre stage as Nick tries to figure out how to navigate his parents’ break-up, stand up to bullies, and impress the girl of his dreams. These challenges – which seem even harder than scoring a tie-breaking, game-winning goal – change his life, as well as his best friend’s. Angleberger, Tom. Fuzzy At Vanguard One Middle School (aka Vainglorious), the halls are crawling with robots, but Fuzzy isn’t your run-of-the-mill cyborg. When Fuzzy enrolls at Vainglorious as part of the Robot Integration Program, he is quickly befriended by Max, who is determined to help him learn everything he needs to know. The middle school of the future is just as fraught with crazy kids, tricky teachers, and bad smells as the middle school of today. Add in some evil schemers, and you have real trouble. Together, Max and Fuzzy reveal the super-secret, nefarious purpose behind the Robot Integration Program. They must fight to save the school before it’s too late. Brown, Gavin. Josh Baxter Levels Up Josh Baxter is sick and tired of hitting the reset button. It's not easy being the new kid for the third time in two years. One mistake and now the middle school football star is out to get him.