Aspiring India: the Politics of Mothering, Education Reforms, and English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post Offices

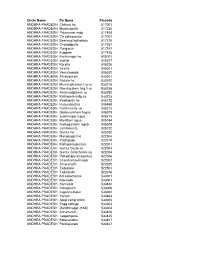

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Issues in Indian Politics –

ISSUES IN INDIAN POLITICS – Core Course of BA Political Science - IV semester – 2013 Admn onwards 1. 1.The term ‘coalition’ is derived from the Latin word coalition which means a. To merge b. to support c. to grow together d. to complement 2. Coalition governments continue to be a. stable b. undemocratic c. unstable d. None of these 3. In coalition government the bureaucracy becomes a. efficient b. all powerful c. fair and just d. None of these 4. who initiated the systematic study of pressure groups a. Powell b. Lenin c. Grazia d. Bentley 5. The emergence of political parties has accompanied with a. Grow of parliament as an institution b. Diversification of political systems c. Growth of modern electorate d. All of the above 6. Party is under stood as a ‘doctrine by a. Guid-socialism b. Anarchism c. Marxism d. Liberalism 7. Political parties are responsible for maintaining a continuous connection between a. People and the government b. President and the Prime Minister c. people and the opposition d. Both (a) and (c) 1 8. The first All India Women’s Organization was formed in a. 1918 b. 1917 c.1916 d. 1919 9. ------- belong to a distinct category of social movements with the ideology of class conflict as their basis. a. Peasant Movements b. Womens movements c. Tribal Movements d. None of the above 10.Rajni Kothari prefers to call the Indian party system as a. Congress system b. one party dominance system c. Multi-party systems d. Both a and b 11. What does DMK stand for a. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

E-Digest on Ambedkar's Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology

Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology An E-Digest Compiled by Ram Puniyani (For Private Circulation) Center for Study of Society and Secularism & All India Secular Forum 602 & 603, New Silver Star, Behind BEST Bus Depot, Santacruz (E), Mumbai: - 400 055. E-mail: [email protected], www.csss-isla.com Page | 1 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Preface Many a debates are raging in various circles related to Ambedkar’s ideology. On one hand the RSS combine has been very active to prove that RSS ideology is close to Ambedkar’s ideology. In this direction RSS mouth pieces Organizer (English) and Panchjanya (Hindi) brought out special supplements on the occasion of anniversary of Ambedkar, praising him. This is very surprising as RSS is for Hindu nation while Ambedkar has pointed out that Hindu Raj will be the biggest calamity for dalits. The second debate is about Ambedkar-Gandhi. This came to forefront with Arundhati Roy’s introduction to Ambedkar’s ‘Annihilation of Caste’ published by Navayana. In her introduction ‘Doctor and the Saint’ Roy is critical of Gandhi’s various ideas. This digest brings together some of the essays and articles by various scholars-activists on the theme. Hope this will help us clarify the underlying issues. Ram Puniyani (All India Secular Forum) Mumbai June 2015 Page | 2 E-Digest - Ambedkar’s Appropriation by Hindutva Ideology Contents Page No. Section A Ambedkar’s Legacy and RSS Combine 1. Idolatry versus Ideology 05 By Divya Trivedi 2. Top RSS leader misquotes Ambedkar on Untouchability 09 By Vikas Pathak 3. -

Is a Cruelly Well-Made Bad-Seed Horror Movie

13 SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2019 THRILLER) NEW 1-COLD PURSUIT (15+) (ACTION/CRIME/DRAMA) NEW CITYCENTRE NARGIS FAKHRI, SACHIN JOSHI, MONA SINGH, VIVAN BHATENA LIAM NEESON, EMMY ROSSUM, LAURA DERN OASIS JUFFAIR DAILY AT: 12.30 + 6.00 + 11.30 PM DAILY AT: 10.45 AM + 1.15 + 3.45 + 6.15 + 8.45 PM + (11.15 PM 1-COLD PURSUIT (15+) (ACTION/CRIME/DRAMA) NEW THURS/FRI) 1-COLD PURSUIT (15+) (ACTION/CRIME/DRAMA) NEW LIAM NEESON, EMMY ROSSUM, LAURA DERN 7- KUMBALANGI NIGHT ( ) (MALAYALAM) NEW LIAM NEESON, EMMY ROSSUM, LAURA DERN DAILY AT: 10.30 AM + 11.30 + 1.00 + 2.00 + 3.30 + 4.30 + 6.00 + 2-THE LEGO MOVIE 2 (G) (ANIMATION/ACTION/AD- FAHADH FAASIL, SHANE NIGAM, SOUBIN SHAHIR VENTURE/COMEDY) NEW DAILY AT: 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM 7.00 + 8.30 + 9.30 + 11.00 PM + 12.00 MN + (12.30 MN + 1.00 AM FROM THURSDAY 07TH: (12.45 MN THURS/FRI) DAILY AT (VIP): 12.45 + 3.15 + 5.45 + 8.15 + 10.45 PM THURS/FRI) CHRIS PRATT, ELIZABETH BANKS, WILL ARNETT DAILY AT (VIP I): 11.00 AM + 1.30 + 4.00 + 6.30 + 9.00 + 11.30 PM 8-GLASS (PG-15) (THRILLER) DAILY AT: 11.45 AM + 2.00 + 4.15 + 6.30 + 8.45 + (11.00 PM THURS/ DAILY AT (VIP II): 12.30 + 3.00 + 5.30 + 8.00 + 10.30 PM FRI) 2-THE LEGO MOVIE 2 (G) (ANIMATION/ACTION/AD- JJAMES MCAVOY, BRUCE WILLIS, SAMUEL L. -

The Pneumatic Experiences of the Indian Neocharismatics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE PNEUMATIC EXPERIENCES OF THE INDIAN NEOCHARISMATICS By JOY T. SAMUEL A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham June 2018 i University of Birmingham Research e-thesis repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and /or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any success or legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. i The Abstract of the Thesis This thesis elucidates the Spirit practices of Neocharismatic movements in India. Ever since the appearance of Charismatic movements, the Spirit theology has developed as a distinct kind of popular theology. The Neocharismatic movement in India developed within the last twenty years recapitulates Pentecostal nature spirituality with contextual applications. Pentecostalism has broadened itself accommodating all churches as widely diverse as healing emphasized, prosperity oriented free independent churches. Therefore, this study aims to analyse the Neocharismatic churches in Kerala, India; its relationship to Indian Pentecostalism and compares the Sprit practices. It is argued that the pneumatology practiced by the Neocharismatics in Kerala, is closely connected to the spirituality experienced by the Indian Pentecostals. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

DEPARTMENT of HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION 9 Physics

No. EX II (2)/00001/HSE/2017 DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION HIGHER SECONDARY EXAM - MARCH 2017 LIST OF EXTERNAL EXAMINERS (Centre wise) 9 Physics District: Pathanamthitta Sl.No School Name External Examiner External's School No. Of Batches 1 03001 : GOVT. BHSS, ADOOR, BEENA G 03031 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N V HSS, ANGADICAL SOUTH, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04734285751, 9447117229 <=15 2 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, MANJU.V.L 03041 8 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Junior (Physics) K.R.P.M. HSS, SEETHATHODE, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9495764711 <=15 3 03002 : GOVT. HSS, CHITTAR, THOMAS CHACKO 03010 4 VADASSERIKARA, HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT BOYS Ph: Ph: , 9446100754 HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA,PATH ANAMTHITTA 30 4 03003 : GOVT. HSS, BIJU PHILIP 03050 6 EZHUMATTOOR, HSST Senior (Physics) TECHNICAL HSS, MALLAPPALLY EAST.P.O, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: 04812401131, 9447414839 10 Ph: PATHANAMTHITTA, 689584 5 03004 : GOVT.HSS, SHEEBA VARGHESE 03045 7 KADAMMANITTA, HSST Senior (Physics) MT HSS,PATHANAMTHITTA PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: , 9447223589 10 Ph: 6 03005 : K annasa Smaraka GOVT HSS, JESSAN VARUGHESE 03016 8 KADAPRA, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) M G M HSS, THIRUVALLA, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04692702200, 9496212211 10 7 03006 : GOVT HSS, KALANJOOR, LEKSHMI.P.S 03009 8 PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) GOVT HSS KONNI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: , 9447086029 14 8 03007 : GOVT HSS, VECHOOCHIRA RAJIMOL P R 03026 4 COLONY, PATHANAMTHITTA HSST Senior (Physics) S N D P HSS, VENKURINJI, PATHANAMTHITTA Ph: Ph: 04735266367, 9495554912 <=15 9 03008 : GOVT -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

The Saffron Wave Meets the Silent Revolution: Why the Poor Vote for Hindu Nationalism in India

THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tariq Thachil August 2009 © 2009 Tariq Thachil THE SAFFRON WAVE MEETS THE SILENT REVOLUTION: WHY THE POOR VOTE FOR HINDU NATIONALISM IN INDIA Tariq Thachil, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 How do religious parties with historically elite support bases win the mass support required to succeed in democratic politics? This dissertation examines why the world’s largest such party, the upper-caste, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has experienced variable success in wooing poor Hindu populations across India. Briefly, my research demonstrates that neither conventional clientelist techniques used by elite parties, nor strategies of ideological polarization favored by religious parties, explain the BJP’s pattern of success with poor Hindus. Instead the party has relied on the efforts of its ‘social service’ organizational affiliates in the broader Hindu nationalist movement. The dissertation articulates and tests several hypotheses about the efficacy of this organizational approach in forging party-voter linkages at the national, state, district, and individual level, employing a multi-level research design including a range of statistical and qualitative techniques of analysis. In doing so, the dissertation utilizes national and author-conducted local survey data, extensive interviews, and close observation of Hindu nationalist recruitment techniques collected over thirteen months of fieldwork. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Tariq Thachil was born in New Delhi, India. He received his bachelor’s degree in Economics from Stanford University in 2003. -

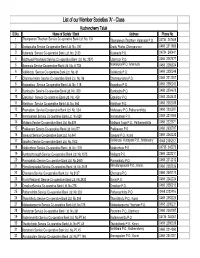

List of Our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No

List of our Member Societies 'A' - Class Kozhencherry Taluk Sl.No. Name of Society / Bank Address Phone No. 1 Thumpamon Thazham Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 134 Thumpamon Thazham, Kulanada P.O. 04734 267609 2 Arattupuzha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 787 Arattu Puzha, Chengannoor 0468 2317865 3 Kulanada Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2133 Kulanada P.O. 04734 260441 4 Mezhuveli Panchayat Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 2570 Ullannoor P.O. 0468 2287477 5 Aranmula Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. A 703 Nalkalickal P.O. Aranmula 0468 2286324 6 Vallikkodu Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 61 Vallikkodu P.O. 0468 2350249 7 Chenneerkkara Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 96 Chenneerkkara P.O. 0468 2212307 8 Kaippattoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 115 Kaipattoor P.O. 0468 2350242 9 Kumbazha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 330 Kumbazha P.O. 0468 2334678 10 Elakolloor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 459 Elakolloor P.O. 0468 2342438 11 Elanthoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 460 Elanthoor P.O. 0468 2362039 12 Pramadom Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No. 534 Mallassery P.O.,Pathanamthitta 0468 2335597 13 Naranganam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.628 Naranganam P.O. 0468 2216506 14 Mylapra Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.639 Mailapra Town P.O., Pathanamthitta 0468 2222671 15 Prakkanam Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.677 Prakkanam P.O. 0468 2630787 16 Vakayar Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.847 Vakayar P.O., Konni 0468 2342232 17 Janatha Service Co-operative Bank Ltd. No.1042 Vallikkodu -Kottayam P.O., Mallassery 0468 2305212 18 Mekkozhoor Service Co-operative Bank Ltd.