For the 7-12 Guide, See ED 392 723. Institute for Peace and Just

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Brian Lynch Full Press Kit(Bio-Discog

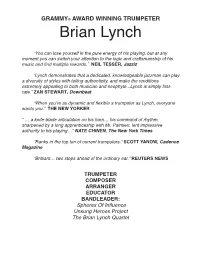

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch “You can lose yourself in the pure energy of his playing, but at any moment you can switch your attention to the logic and craftsmanship of his music and find multiple rewards.” NEIL TESSER, Jazziz “Lynch demonstrates that a dedicated, knowledgeable jazzman can play a diversity of styles with telling authenticity, and make the renditions extremely appealing to both musician and neophyte...Lynch is simply first- rate.” ZAN STEWART, Downbeat “When you’re as dynamic and flexible a trumpeter as Lynch, everyone wants you.” THE NEW YORKER “ … a knife-blade articulation on his horn… his command of rhythm, sharpened by a long apprenticeship with Mr. Palmieri, lent impressive authority to his playing…” NATE CHINEN, The New York Times “Ranks in the top ten of current trumpeters.” SCOTT YANOW, Cadence Magazine “Brilliant… two steps ahead of the ordinary ear.” REUTERS NEWS TRUMPETER COMPOSER ARRANGER EDUCATOR BANDLEADER: Spheres Of Influence Unsung Heroes Project The Brian Lynch Quartet Brian Lynch "This is a new millennium, and a lot of music has gone down," Brian Lynch said several years ago. "I think that to be a jazz musician now means drawing on a wider variety of things than 30 or 40 years ago. Not to play a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but to blend everything together into something that has integrity and sounds good. Not to sound like a pastiche or shifting styles; but like someone with a lot of range and understanding." Trumpeter and Grammy© Award Winner Brian Lynch brings to his music an unparalleled depth and breadth of experience. -

Sant Kirpal Singh: Guru Nanak's JAP JI

Sant Kirpal Singh: Guru Nanak's JAP JI the JAP JI The Message of Guru Nanak Literal Translation of the original Punjabi text with Introduction and Commentary by Kirpal Singh Dedicated to the Almighty God working through all Masters Who have come and Baba Sawan Singh Ji Maharaj at whose Lotus Feet the translator imbibed sweet Elixir of Holy Naam - the Word First published by Ruhani Satsang, Delhi 1959 http://www.ruhanisatsangusa.org/jj/title.htm (1 of 3) [3/6/2003 4:55:48 AM] Sant Kirpal Singh: Guru Nanak's JAP JI Fourth Edition, 1972 No copyright notes: regarding this web published version of "Jap Ji" Spanish translation TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface INTRODUCTION Introduction--What Is Jap Ji? Religion: Objective and Subjective Divine Will--How Is It Revealed? The Objective and Subjective Aspects of Naam Evidences from the Various Religions (i) Christianity (ii) Hinduism (iii) Mohammedanism Sound Differentiated (i) Misery and Pleasure Defined (ii) Advantages Accruing from Inner Communion of the Soul with Naam or Surat Shabd Yoga Simran--What it means and its uses Three Grand Divisions and their features (i) Man Is an Epitome of the Three Grand Divisions of the creation http://www.ruhanisatsangusa.org/jj/title.htm (2 of 3) [3/6/2003 4:55:48 AM] Sant Kirpal Singh: Guru Nanak's JAP JI (ii) Possibility of Communion of the Microcosm with the Macrocosm Regions (iii) Concentration of Spirit-Current Is Necessary Before It Can Rise Into Higher Spiritual Planes (iv) Uses of the Three Restrictions and their Process God-Man (i) Without a God-Man, the Mystery -

B O L L E T T I N O Grand President’S Welcome Back Branch 179! Monthly Message by Andrew Pappani It Seems Like We Were Just in Spring

December 2017 Italian Catholic Federation Anno 93 No. 11 B O L L E T T I N O Grand President’s Welcome Back Branch 179! Monthly Message by Andrew Pappani It seems like we were just in spring. We flew through summer, now we are almost out of Fall. Where did the time go? We are in the season for being thankful for what we have, thankful for our health, thankful for our family and friends. Now it’s time for giving back to the people we love, give to the homeless, the needy and the people who just need a helping hand. At the time of this writing I just attended the Los Angeles Archdiocese Bishop Day. In Most Reverend Joseph Brennan’s homily he spoke about giving, how we always give away the used items we no longer want any more or give can goods that we don’t like, but, • Newly initiated members of Br. 179 St. Dorothy. he said we should give things away that we really want and things we like give Andy Pappani initiated the 37 charter n Sunday, November 12, 2017, the away. I also attended the reopening of St. O members with help from CC Grand Italian Catholic Federation re-welcomed Dorothy, Branch 179 in Glendora, Ca. Treasurer Denise Antonowicz and CC St. Dorothy, Branch 179 back into the Father Mark Warnstedt’s homily was about Immediate Past Grand President Leonard Federation. St. Dorothy is located in forgiving others because you don’t know Zasoski, Jr. Glendora, California. what tomorrow will bring.Tell your spouse The new branch officers are: how much you love them; hug your kids; This re-opening came to be under the your parents, your friends; phone them, tell guidance and leadership of the Central President: Geoff Novall o • Andy Pappani and Br. -

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch “You can lose yourself in the pure energy of his playing, but at any moment you can switch your attention to the logic and craftsmanship of his music and find multiple rewards.” NEIL TESSER, Jazziz “Lynch demonstrates that a dedicated, knowledgeable jazzman can play a diversity of styles with telling authenticity, and make the renditions extremely appealing to both musician and neophyte...Lynch is simply first- rate.” ZAN STEWART, Downbeat “When youʼre as dynamic and flexible a trumpeter as Lynch, everyone wants you.” THE NEW YORKER “ … a knife-blade articulation on his horn… his command of rhythm, sharpened by a long apprenticeship with Mr. Palmieri, lent impressive authority to his playing…” NATE CHINEN, The New York Times “Ranks in the top ten of current trumpeters.” SCOTT YANOW, Cadence Magazine “Brilliant… two steps ahead of the ordinary ear.” REUTERS NEWS TRUMPETER COMPOSER ARRANGER EDUCATOR BANDLEADER: “Spheres Of Influence” “Unsung Heroes Project” The Brian Lynch Big Band Brian Lynch "This is a new millennium, and a lot of music has gone down," Brian Lynch said several years ago. "I think that to be a straight-ahead jazz musician now means drawing on a wider variety of things than 30 or 40 years ago. Not to play a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but to blend everything together into something that sounds good. It doesn't sound like pastiche or shifting styles; it's people with a lot of knowledge." Few musicians embody this 21st century credo as profoundly as the 48-year-old trumpet master. -

April 2021 • a Publication of the Recreation Centers of Sun City, Inc

ISSUE #233 • APRIL 2021 • A PUBLICATION OF THE RECREATION CENTERS OF SUN CITY, INC. Stay in the loop! Guest Policy Changes Under Consideration Get RCSC News Alert RCSC Management presented a proposal at the recent Board of Emails, sign up at: Directors meeting on March 25, 2021 that would change the current Current COVID-19 Rules & www.suncityaz.org policy regarding guests. With the Sun City Visitors Center continu- ing to be closed at this time to in-person visitors, a proposal to Regulations as of March 10, 2021 change the “no visitor” policy immediately was not recommended. Email addresses However, the proposal did recommend that escorted guests be REQUIREMENTS FOR USE OF ALL RCSC FACILITIES remain confidential allowed at some outdoor activities beginning on Saturday, May 1, • Prior to entering RCSC facilities, RCSC has implemented 2021. COVID-19 symptom screening with signage. Please read and evaluate whether you meet the criteria to enter RCSC facili- If the Board has chosen to move forward with this proposal, two ties. Anyone with potential symptoms may not enter or use more readings will be required at the Board meetings scheduled for RCSC facilities. INDEX Monday, April 12 and Thursday, April 29, 2021. • Hand sanitizer is required upon entry to RCSC facilities and All guests will be required to be escorted by an RCSC Cardholder offices. Users may utilize the sanitizer provided by RCSC. News Page 01-03 and participation would be limited to the following outdoor activi- • Face masks are always required while indoors except in show- ties: Bocce, Fishing, Horseshoes, Mini Golf, Pickleball, Softball, Tennis ers, indoor pools and indoor spas. -

Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin

Ithaca College Digital Commons IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-15-1996 Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin Toshiko Akiyoshi Lew Tabackin Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Akiyoshi, Toshiko; Tabackin, Lew; and Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra, "Concert: Toshiko Akiyoshi Jazz Orchestra & Lew Tabackin" (1996). All Concert & Recital Programs. 7545. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/7545 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons IC. ITHACA COLLEGE CONCERTS 1996-97 TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI JAZZ ORCHESTRA FEATURING LEW TABACKIN TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI, conductor, composer, arranger LEW TABACKIN, tenor saxophone and flute 13aru2 Toshiko Akiyoshi 1.tm Doug Weiss* Drums Terry Clarke ~ Dave Pietro* Lew Tabackin Jim Snidero Walt Weiskopf Scott Robinson Trumpet Mike Ponella* John Eckert Scott Wendhodt Joe Magnelli Trombone Scott Whitfield* Steve Amour Luis Bonilla Tim Newman Percussion Valtinho Road Manager George Whitington Ford Hall Auditorium Sunday, September 15, 1996 8:15 p.m. • section leader Management: The Berkeley Agency, 2608 Ninth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI Toshiko Akiyoshi was born in Manchuria, China, and was considering a career in medicine when her family returned to live in Japan. She already had some training as a classical pianist, when she got a job playing in a dance hall in Beppu. Her family wasn't thrilled with the idea, but they finally agreed that she could play until the school year began. -

Alex Loznak '19 Is Suing the U.S. Government for the Right to a Safer Planet

Summer 2020 PREVAILING OVER PANDEMIC ALUMNI SHARE STORIES OF LIFE DURING COVID-19 VIRTUAL CLASS DAY THE SHOW DID GO ON! CONGRATS TO THE Columbia CLASS OF 2020 College RACHEL FEINSTEIN ’93 SCENES FROM HER Today FIRST MAJOR MUSEUM RETROSPECTIVE TAKING Alex Loznak ’19 is suing the U.S. government CLIMATE CHANGE for the right to TO COURT a safer planet Contents Columbia College CCT Today VOLUME 47 NUMBER 4 SUMMER 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Alexis Boncy SOA’11 EXECUTIVE EDITOR Lisa Palladino DEPUTY EDITOR 10 14 24 Jill C. Shomer ASSOCIATE EDITOR Anne-Ryan Sirju JRN’09 FORUM EDITOR features Rose Kernochan BC’82 CONTRIBUTING EDITOR 10 Thomas Vinciguerra ’85 ART DIRECTOR Eson Chan Taking Climate Change to Court Alex Loznak ’19 is one of a team of young people suing Published quarterly by the the U.S. government for the right to a safer planet. Columbia College Office of Alumni Affairs and Development By Anne-Ryan Sirju JRN’09 for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends of Columbia College. CHIEF COMMUNICATIONS 14 AND MARKETING OFFICER Bernice Tsai ’96 “What Has Your Pandemic ADDRESS Experience Been Like?” Columbia College Today Columbia Alumni Center Fourteen alumni tell us how COVID-19 has shaped their lives. 622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl. New York, NY 10025 By the Editors of CCT PHONE 212-851-7852 24 EMAIL [email protected] Uniquely United WEB college.columbia.edu/cct The College produced its first-ever virtual ISSN 0572-7820 Class Day to honor the Class of 2020. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect official positions of Columbia College 25 or Columbia University. -

Philosophy and Practice 1 JAINA Education Series 302 Level - 3

Jain Philosophy and Practice 1 JAINA Education Series 302 Level - 3 Compiled by JAINA Education Committee Pravin K. Shah, Chairperson Federation of Jain Associations in North America This book has no copyright. Please use the religious material respectfully We are interested in your comments. Use the following address for communication: Published and Distributed by: JAINA Education Committee (Federation of Jain Associations in North America) Pravin K. Shah, Chairperson 509 Carriage Woods Circle Raleigh, NC 27607-3969 USA Email - [email protected] Telephone and Fax - 919-859-4994 Website – www.jaina.org 7 DEDICATED TO Young Jains of America (YJA) (www.yja.org) Young Jain Professionals (YJP) and (www.yjponline.org) Jain Päthashälä Teachers of North America (www.jaina.org) For their continued efforts and commitment in promoting religious awareness, nonviolence, reverence for all life forms, protection of the environment, and a spirit of compassionate interdependence with nature and all living beings. As importantly, for their commitment to the practice of Jainism, consistent with our principles, including vegetarianism and an alcohol/drug free lifestyle. We especially appreciate the efforts of all the Päthashälä Teachers in instilling the basic values of Jainism, and promoting principles of non-violence and compassion to all youth and adults. Special thanks to all Jain Vegan and alcohol/drug free youths and adults for inspiring us to see the true connection between our beliefs and our choices. A vegan and alcohol/drug free lifestyle stems from a desire to minimize harm to all animals as well as to our own body, mind, and soul. As a result, one avoids the use of all animal products such as milk, cheese, butter, ghee, ice cream, silk, wool, pearls, leather, meat, fish, chicken, eggs and refrains from all types of addictive substances such as alcohols and drugs. -

Style Worship Sharon Sheridan [email protected] Diocesan Life Major Photography: Marc Yves Regis I Marcregis.Com

CONTENTS VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 I OCTOBER 2013 Perspectives The Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut Diocesan House 2 A contradiction to the world Joseph Shepley 1335 Asylum Avenue I Hartford, CT 06105 3 Listening to stories Danielle Tumminio 860.233.4481 I www.ctepiscopal.org 4 Joining in God’s mission Ian T. Douglas Publisher: The Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut Features Bishops: The Rt. Rev. Ian T. Douglas 6 Fortune’s story Karin Hamilton The Rt. Rev. James E. Curry The Rt. Rev. Laura J. Ahrens 10 Walking forward in peace Karin Hamilton Editor: Karin Hamilton, Canon for Mission 12 The Way of the Cross Communication & Media ı [email protected] Design: Elizabeth Parker ı EP Graphic Design 14 ‘Flash mob’ - style worship Sharon Sheridan [email protected] Diocesan Life Major Photography: Marc Yves Regis ı marcregis.com Photography: Episcopal News Service 16 Caring for this fragile earth, our island home Laura J. Ahrens Karin Hamilton Richard Lammlin 17 Praying for the peace of Jerusalem Laura J. Ahrens Duane E. Langenwalter Sharon Sheridan/Episcopal News Service 18 CT Episcopalians announce new interfaith partnership Change of address and other circulation correspondence 18 Parishes in transition: Top 10 FAQs Tim Hodapp should be addressed to [email protected]. 20 Dissolving boundaries Audrey Scanlan The Episcopal Diocese of Connecticut 22 Offering a prayer in a time of conflict Jim Curry (www.ctepiscopal.org) is a community of 60,000 members worshipping in 168 congregations across the 24 Profile of Marsha McCurdy Frankye Regis state. It is part of The Episcopal Church. 26 Profile of Mark Byers Frankye Regis The Episcopal Church 28 Profile of Cathy Ostuw Karin Hamilton (www.episcopalchurch.org) is a community of two million members in 110 dioceses across the United 30 What is God up to in Connecticut? Karin Hamilton States and in 13 other countries. -

Carl Sandburg - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Carl Sandburg - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Carl Sandburg(6 January 1878 – 22 July 1967) Carl Sandburg was an American writer and editor, best known for his poetry. He won three Pulitzer Prizes, two for his poetry and another for a biography of <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/abraham-lincoln/">Abraham Lincoln</a>. H. L. Mencken called Carl Sandburg "indubitably an American in every pulse- beat." <b> Biography</b> Sandburg was born in Galesburg, Illinois, to parents of Swedish ancestry. At the age of thirteen (During Eighth grade) he left school and began driving a milk wagon. From the age of about fourteen until he was seventeen or eighteen, he worked as a porter at the Union Hotel barbershop in Galesburg. After that he was on the milk route again for 18 months. He then became a bricklayer and a farm laborer on the wheat plains of Kansas. After an interval spent at Lombard College in Galesburg, he became a hotel servant in Denver, then a coal-heaver in Omaha. He began his writing career as a journalist for the Chicago Daily News. Later he wrote poetry, history, biographies, novels, children's literature, and film reviews. Sandburg also collected and edited books of ballads and folklore. He spent most of his life in the Midwest before moving to North Carolina. Sandburg volunteered to go to the military and was stationed in Puerto Rico with the 6th Illinois Infantry during the Spanish–American War, disembarking at Guánica, Puerto Rico on July 25, 1898. -

Edward Gilpin Johnson the Best Letters of Charles Lamb

EDWARD GILPIN JOHNSON THE BEST LETTERS OF CHARLES LAMB 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted LAUREL-CROWNED LETTERS CHARLES LAMB It may well be that the "Essays of Elia" will be found to have kept their perfume, and the LETTERS OF CHARLES LAMB to retain their old sweet savor, when "Sartor Resartus" has about as many readers as Bulwer's "Artificial Changeling," and nine tenths even of "Don Juan" lie darkening under the same deep dust that covers the rarely troubled pages of the "Secchia Rapita." A.C. SWINBURNE No assemblage of letters, parallel or kindred to that in the hands of the reader, if we consider its width of range, the fruitful period over which it stretches, and its typical character, has ever been produced. W.C. HAZLITT ON LAMB'S LETTERS. THE BEST LETTERS OF CHARLES LAMB Edited with an Introduction BY EDWARD GILPIN JOHNSON A.D. 1892. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION LETTER I. To Samuel Taylor Coleridge II. To Coleridge III. To Coleridge IV. To Coleridge V. To Coleridge VI. To Coleridge VII. To Coleridge VIII. To Coleridge IX. To Coleridge X. To Coleridge XI. To Coleridge XII. To Coleridge XIII. To Coleridge XIV. To Coleridge XV. To Robert Southey XVI. To Southey XVII. To Southey XVIII. To Southey XIX. To Thomas Manning XX. To Coleridge XXI. To Manning XXII. To Coleridge XXIII. To Manning XXIV. To Manning XXV. To Coleridge XXVI. To Manning XXVII. To Coleridge XXVIII. To Coleridge XXIX. To Manning XXX. To Manning XXXI. To Manning XXXII. To Manning XXXIII. To Coleridge XXXIV. To Wordsworth XXXV. -

Senators in Row Over Huston Fund

m t h e WEATHEB -Forecast by D. «• Weather Boreau, . Hartford. NET PBES^.BDN /-.. AVEBAUE DAILY OlBCDlATlON - Bain tonight and probably Wed for tlie Month of Febmary» 1930 nesday morning; slightly warmer ■ tonight, colder Wednesday. ^ 5,503 Uembera of »•»* Ao«IH Bnreau of f^rcnlationa PRICE THREE CEN’EB TWELVE PAGES SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, MARCH 18, (Classified Advertising on Page 10) VOL. XLIV., NO. 143. AS “OLD IRONSIDES” WENT TO SEA AG AIN !i, SENATORS IN ROW - i OVER HUSTON FUND ____ <♦; ' ■ '■ — Issue Subpoena to Obtain Ibutthreemen Thirty Persms Invites Italian F oreip Min Records of $36,000 De- RUNTHE HOUSE, ister to Private Confer posit Made by the G. 0. P. In Fire On Steamer ence to See If an Agree HOWARD AVOWS ment Cannot Be Arranged Leader Last Year, T, * March 1 8 Passengers and crew, squeezing ■ ! Bogota, .,o" through portholes to escape the! (A P .)—The bodies of between ZO behind them, jumped into i With France— Mnssolmi Washington. March Ncbraska CongTCSsman De- and 30 passengers and crew of the ' water the surface of which Aftcr a heated exchange iMth c^nair * o river steamer ‘ Bucaramanga were , was covered with petroleum releas- man Huston of the Republican Na .0 tu. Magdalena rlvef « , M In Telephonic Communi tional committee and a row among nounces Gag Rule in Low La Dorada today. xa. J ' the water were burned to death be-! its members, the Senate Lobby com ■The Bucaramanga berthed at tne fore they coul swim away. cation With His Delegates small river town was destroyed yes er Chamber— Contrasts Only ten paissengers of .