York's 'African-Style' Severan Pottery Reconsidered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop 1. Soldiers on Every Street Corner: the War Is Announced in York

Stop 1. Soldiers on every street corner: the war is announced in York Stand in front of the Yorkshire Museum, on the steps looking out into the Gardens. During the First World War, newspapers were the main source of information for the public, explaining what was happening at home and abroad as well as forming the basis for pro-war propaganda. In York, the building that currently operates as the City Screen Picturehouse, later on you will see it between stops 4 and 5, was once the headquarters of the Yorkshire Herald Newspaper. In 1914 there were around 100,000 people living in York, half of the city’s current population, and York considered itself the capital of Yorkshire and the whole of the North of England. The Local newspapers did not wholly prepare the city’s inhabitants for Britain entering the war, as the Yorkshire Evening Press stated soon after war had been announced that ‘the normal man cared more about the activities of the household cat than about events abroad’. At the beginning of the 20th century the major European countries were incredibly powerful and had amassed great wealth, but competition for colonies and trade had created a European continent rife with tensions between the great powers. June 28th 1914 saw the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire Arch-Duke Ferdinand and his wife Sophia while on a diplomatic trip to Sarajevo by a Yugoslav Nationalist who was fighting for his country’s independence. This triggered the chain reaction which culminated in war between the European powers. -

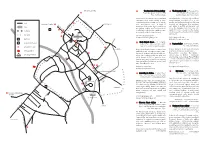

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday Evening 26Th August and All Day Bank Holiday Monday 27Th August 2018 Diversions to Bus Services

Micklegate Soap Box Run Sunday evening 26th August and all day Bank Holiday Monday 27th August 2018 Diversions to bus services Bank Holiday Monday 27th August is the third annual Micklegate Run soap box event, in the heart of York city centre. Micklegate, Bridge Street, Ouse Bridge and Low Ousegate will all be closed for the event, with no access through these roads or Rougier Street or Skeldergate. Our buses will divert: -on the evening of Sunday 26th August during set up for the event. -all day on Bank Holiday Monday 27th August while the event takes place. Diversions will be as follows. Delays are likely on all services (including those running normal route) due to increased traffic around the closed roads. Roads will close at 18:10 on Sunday 26th, any bus which will not make it through the closure in time will divert, this includes buses which will need to start the diversion prior to 18:10. Route 1 Wigginton – Chapelfields – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 2 Rawcliffe Bar Park & Ride – will be able to follow its normal route throughout. Route 3 Askham Bar Park & Ride – Sunday 26th August: will follow its normal route up to and including the 18:05 departure from Tower Street back to Askham Bar Park & Ride. The additional Summer late night Shakespeare Theatre buses will then divert as follows: From Askham Bar Park & Ride, normal route to Blossom Street, then right onto Nunnery Lane (not serving the Rail Station into town), left Bishopgate Street, over Skeldergate Bridge to Tower Street as normal. -

OBERHOFFER Herr RW 14 Bootham Crescent

600 , YORK CLASSIFIED TRADES• • Child Wm. Storr, 34 Clarence st Dixon Chas. 7 Lime st. Hungate Hanforth T. W. 38 Bishopthorpe Dixon John, 9, 10 & 11 Garden roa.d street, Groves Naylor John, Mus Doe. Oxon. Eccles Wm. 5 Skeldergate (organist and choir master), 9 Fail Geo. 20 Layerthorpe Grosvenor terrace Fearby W. H. 62 Walmgate Newton Wm. 2 Peckitt st Gilbank Thos. 1 Bromley st. Lee. Newton Wm. & Mrs. 5 Wilton ter man road Fulford road Goates Geo.61 Walmgate OBERHOFFER Herr R. W. 14 Green Mrs. 41 Bright st. Leeman Bootham crescent road Padell Herr C. G. Park cottage, HackwelI Wm. Charles st. & CIar Park st. ence street Sample Arthur, 36 Grosvenor ter Hardcastle Chas. 34 Layerthorpe Smith Thos. 43 Marygate Harrison .Tohn, 16 & 18 Garden Wright Wm. Robt. Mus. Bac. Oxon. place, Rungate 20 St. Saviourga.te Rarrison Bobt. 1 Park crescentr Provision Dealers. Groves Alderson Wm. 31 Gillygate Ressay Miss Emma, 35 Shambles Allen Joseph, 1 Kingsland terrace, Hodgson Jas. 58 Walmgate Leeman road Hodgson John Wm. post office, Andrew Jos. 2 Fishergate Olifton Anson Mrs. E. 21 Grove place, Hodgson Boger, 46 Tanner row Groves Rodgson Thos. 14 Layerthorpe Atkinson Ed. 23 Blossom st Holmes Mrs. M. A. 27 Layerthorpe Barrow Samuel J. 24 Layerthorpe Horsley Carton B, 6 Heworth rd Beedham Rd. 1 Vyner st Howden H. J. 1 Ranover st. Lee· Benson Wm. Townend st & Mans man road field place Ruby Fred. 28 North st Beresford Jas. Elliott, 39 Low Ruby Mrs. Jane. 40 Townend,st Petergate Rumphrey Geo. 42 Fossgate Blair Chas. -

Calvert Francis, 70, Micklegate Ters A.Nd Binders. .Calve~ James, 59, Bootham •'

TRADES AND PROFESSIONS. 481 • Othick Henry, 20, Monkgate Roberts Henry, 2J, High Petergate • Palphramand Edmd., 49, Aldwrk Sampson John, 52, Coney street Prince George, Acomb Shillito Joseph, 17, Spnrriergate • Strangeway Rbt., Malt Shovel yd • Sotheran Henry, 44, Coney street Tate Thomas, 117, Walmgate Sunter Robert, 23, Stonegate Tonington J., yd. 45. Lawrence 8t Weightman Thos., 44. Goodramgt Whaite Elisha. (& spring cartmkr.,) Boot and Shoe Ma.kers. yard 48, 'Blossom street Allan Benjamin. 2i, Colliergate Walker Edward, Foss bridge Atkinson John, J4. Barker bill • Waller Thomas, 70, Micklegate Aveson Rog-er, 4, 'Dundas street Wpllburne William, Layerthorpe Avison Richard, 19. Haver lane • Wilks George, 38. Bootham row Baines William, 7, Brnnswick pI Wilson John, 70, Walmgate Ballance James, Acomb Bone Crushers & Gua.no Dlrs. Balli~er John, 5, Hope street Barnby Thomas. 7, Ogleforth Dixon Joseph. George street Barnard William, 7, Albert street Hunt Joseph, 19, Aldwark Mills Thomas. 37, Skeldergate Barnett William, 21, Coney street Bartle William. 19, Pavement Richardson Henry, Skeldergate Bean John, 140, Walmgate Bookbinders. Birkinshaw Thomas, 21, Monkgate Acton Geo., Church In.• Coppergt Blakebrough Richard, Abbott st Brassington RIJd., 28, Waterloo pi Bolton Thomas, Regent street Gill Robert, J69. Walmgate Bowman John, 37, Goodramgate Lyon Joseph, 19, Regent square Bowman Robert, 24, Layerthorpe Nicholson H.•22,Queen st.Tannr.rw Briggs William, 7, George street Pickering George, et. 14, Fossgate Briggs William, 17, Parliament st Sumner Oliver, 23, Ogleforth Brown William, 2, Little Shambles Teasdale John, Gazette Office et., . Brown William, 55, Hope street J3, High Ousegate Burton William, Clifton Walton Thomas, 23, Aldwark Butler J ames, 23, Bootham row Booksellers, Sta.tioners, Prin- Calvert Francis, 70, Micklegate ters a.nd Binders. -

Creating the Slum: Representations of Poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate Districts of York, 1875-1914

Laura Harrison Ex Historia 61 Laura Harrison1 University of Leeds Creating the slum: representations of poverty in the Hungate and Walmgate districts of York, 1875-1914 In his first social survey of York, B. Seebohm Rowntree described the Walmgate and Hungate areas as ‘the largest poor district in the city’ comprising ‘some typical slum areas’.2 The York Medical Officer of Health condemned the small and fetid yards and alleyways that branched off the main Walmgate thoroughfare in his 1914 report, noting that ‘there are no amenities; it is an absolute slum’.3 Newspapers regularly denounced the behaviour of the area’s residents; reporting on notorious individuals and particular neighbourhoods, and in an 1892 report to the Watch Committee the Chief Constable put the case for more police officers on the account of Walmgate becoming increasingly ‘difficult to manage’.4 James Cave recalled when he was a child the police would only enter Hungate ‘in twos and threes’.5 The Hungate and Walmgate districts were the focus of social surveys and reports, they featured in complaints by sanitary inspectors and the police, and residents were prominent in court and newspaper reports. The area was repeatedly characterised as a slum, and its inhabitants as existing on the edge of acceptable living conditions and behaviour. Condemned as sanitary abominations, observers made explicit connections between the physical condition of these spaces and the moral behaviour of their 1 Laura ([email protected]) is a doctoral candidate at the University of Leeds, and recently submitted her thesis ‘Negotiating the meanings of space: leisure, courtship and the young working class of York, c.1880-1920’. -

Guildhall Greenlight

Fishergate GreenLight The Newsletter of York Green Party May 2016 All residents are warmly invited to the annual meeting of the Guildhall Ward Committee Thursday 26th May in the Council Chamber, The Guildhall, St Helen’s Square, York YO1 9QL 6.30 – 7.00pm informal chat with ward councillors 7.00 – 9.00pm ward meeting A chance to enjoy the historic Council Chamber and raise issues with ward councillors. An update on projects funded by the ward committee over the last year; representatives of funded projects will tell us a little about what they have done An update on ward budgets for this year and discussion of our ward aims and objectives (based on what residents told us about priorities at a previous meeting) Report and election of the Guildhall Ward A new residents’ association Planning Panel – local residents who comment on planning applications in the for the Navigation / Walmgate ward – contact us if you are interested in area is starting up. joining the panel Initial meeting to set up a committee on Open space for community news and for Weds. 25th May – contact us if you’d like to residents to raise issues come, and also if you can’t make that time This meeting is for everyone who lives in but would like to be involved anyway. Guildhall ward (if you are getting this newsletter you live in Guildhall ward!). I look forward to meeting you there. Denise Craghill, Green Party councillor for Guildhall Green Party for the common good Promoted by A Chase on behalf of York Green Party, both at 15 Priory Street, York YO1 6ET. -

Scawins Hotel," Family and Easton Mrs

YORK ALPHABETICAL DIRECTORY. 349 • Dyson Benjamin, railway ticket Easton Harry, sl:hoolmasetr, 22 examiner, 40 Thorpe street Rougier st Easton John, j. jrille~, 12 Upper DYSON G. H. (late Abbott), St. Paul's terrace " Scawins Hotel," family and Easton Mrs. 2 Margaret st commercial, Tanner row, East Riding of Yorkshire, Ouse opposite the Old Station and Derwent Division Constab gates (See advt. before map) lury, Robt. Holtby, clerk; Geo. Clark, sergt. in charge, Alms. Dyson Geo. j. joiner, 2 Fairfax st terrace Dyson Meek, solicitor and commis sioner for oaths, and clerk to the Eastwood Geo. plane manufac school attendance committee, turer, and tool warLhouse, Per· office 56 Coney street severance works, 52 Walmgate Dyson Mrs. E. West View house, Eastwood Geo. rly. workman, 38 Bishopthorpe road Fairfax st Dyson Mrs. H. 40 Bell Vue street Eastwood Geo. labourer, 14 Wood Dyson Thos. solicitor at Birming st. Mill lane ham, 9 Fountayne street Eastwood Panl, j. joiner, 33 Rede Dyson W. B. woollen draper, 29 ness street High Ousegate Eastwood Thos, railway fireman, Eacott Rev. J. 2 Clarendon ter 20 Fenwick st race, Scarcroft road Eaton Mrs. 7 RUtiby plaee Eagle Mrs. milliner, 4 Bridge st Ebor Discount Lo·m Company Eagle Robt. hair cutter 23 Belle Office, 36 Stonegate Vue street Ebor Permanent Building Society, Eagle Thos. j. painter, 4 Bridge st Offices-14 Castlegate, secretary Eagle T.L. tobacconist, 148 Walm E. F. Lewin gate Eccles Chas. general dealer, and Eardley Hy. j. confectioner, 23 marine stores, 6 & 7 Peter lane Buckingham st Eccles Geo. j. joiner, Long Close Earle Hy. -

St Nicks Environment Centre, Rawdon Avenue, York YO10 3FW 01904 411821 | [email protected] |

The list below shows the properties we collect from. Depending on access some properties may have a different collection day to the one shown below. Please contact us to check. Please contact us on the details shown at the bottom of each page. This list was last updated JULY 2021. 202120201 ALDWARK TUE BAILE HILL TERRACE THUR BARLEYCORN YARD FRI BARTLE GARTH TUE BEDERN TUE BISHOPHILL JUNIOR MON BISHOPHILL SENIOR THUR BISHOPS COURT THUR BLAKE MEWS WED BLAKE STREET WED BLOSSOM STREET MON BOLLANS COURT TUE BOOTHAM WED BOOTHAM PLACE WED BOOTHAM ROW WED BOOTHAM SQUARE WED BRIDGE STREET MON BUCKINGHAM STREET THUR BUCKINGHAM COURT THUR BUCKINGHAM TERRACE THUR CASTLEGATE WED CATHERINE COURT WED CHAPEL ROW FRI CHAPTER HOUSE STREET TUE CHURCH LANE MON CHURCH STREET WED CLAREMONT TERRACE WED CLIFFORD STREET WED COFFEE YARD WED COLLEGE STREET TUE COLLIERGATE WED COPPERGATE WED COPPERGATE WALK WED CRAMBECK COURT MON CROMWELL HOUSE THUR CROMWELL ROAD THUR DEANGATE FRI DENNIS STREET FRI St Nicks Environment Centre, Rawdon Avenue, York YO10 3FW 01904 411821 | [email protected] | www.stnicks.org.uk Charity registered as ‘Friends of St Nicholas Fields’ no. 1153739. DEWSBURY COTTAGES MON DEWSBURY COURT MON DEWSBURY TERRACE MON DIXONS YARD FRI FAIRFAX STREET THUR FALKLAND STREET THUR FEASEGATE WED FETTER LANE MON FIRE HOUSE WED FIRE APARTMENTS WED FOSSGATE FRI FRANKLINS YARD FRI FRIARGATE WED FRIARS TERRACE WED GEORGE HUDSON STREET WED GEORGE STREET FRI GILLYGATE WED GLOUCESTER HOUSE WED GOODRAMGATE TUE GRANARY COURT TUE GRANVILLE TERRACE WED GRAPE -

Third Master, JT Grey

LOCAL INTELLIGENCE. 47 Hewitt; Third Master, J. T. Grey; Fourth Master, H. S. Kitts. Manor School, Manor Yard, St. Leonard's Place Head master, Geo. K. Hitchcock; Second master, A. P. Lupton; Third master, 'V. A. Woi-snop. Friends Boys' School, 20, Bootham Master, John Firth Fryer. Elmfield College (Primitive Methodist), Malton Road Governor, Rev. R. Smith; Head master, Thos. Gough, B.Sc.; Resident masters, Wm. Johnson, B.A., H. Haddow, H. A. Knowles, L. H. Leadley, Wm. Freear and J. Tongue. Visit ing masters: W. S. Child (music), C. H. Wakefield (drawing). Yvrkshire School for the Blind (Instituted at York, 1833) in memory of William 'Vilberforce, M.P. for the County of York, 1802 to 1833. Treas., A. H. Russell, Esq.; Supt., Anthony Buckle, B.A.; Hon. Sec., Fredk. James Munby. Admission to the schools and workshops, free at any time. Concerts every Thursday afternoon, at 2.30; admission, Sixpence each. York Certified Industrial Boys' School, Marygate President, The Lord Archbishop of York; superintendent, Wm. Smith; matron, Mrs. Smith; schoolmaster, Thos. Archey; shoe maker, Mr. Croft; tailor, Mr. Wilkinson; bandmaster, C. Birkill; turner, Jas. C. Rudd; cook, Miss Clay; labour master, Mr. Spence; labour-mistress, Miss Boyes. The Girls' School, Lowther Street Hon. sec., A. H. Russell, Esq.; hone treas., R. H. Feltoe, Esq.; matron, Miss Neale; school-mistress, Miss Smith; labour-mistress, Mrs. Wright. Blue Coat School, St. Anthony's Hall, Peasholme Green I Master, Edward Robinson. Grey Coat Girls' School, Monkgate Mistress,Miss J. Greig. NATIONAL SCHOOLS. Clerk to the School Attendance Committee Meek Dyson, solicitor, Coney Street. -

Yorkshire Archaeology Today

YORKSHIRE No.20 ARCHAEOLOGY TODAY Intaglios from York Possibly the earliest Christian artefact from Roman Britain? Inside: YORK Hungate Update ARCHAEOLOGICAL Conisbrough TRUST Micklegate Bar and the Battle of Towton Yorkshire Archaeology Today Spring 2011 Contents Number 20 Editor: Richard Hall Hungate 2011 1 Photo editing, typesetting, design & layout: Lesley Collett Intaglios from York 7 Printed by B&B Press, Rotherham Yorkshire Archaeology Today Micklegate Bar and the Battle of Towton 10 is published twice a year. UK subscriptions: £10.00 a year. A Conundrum in Conisbrough 12 Overseas subscriptions: £14.00 (sterling) a year. To subscribe please send a cheque payable to New Ways to Visualize the Past 16 Yorkshire Archaeology Today to: York Archaeological Trust, 47 Aldwark People First: 18 YO1 7BX Community Archaeology for or through Postgiro/CPP to: People with Learning Difficulties ACCOUNT 647 2753 National Giro, Bootle, Merseyside, GIR 0AA Yorkshire Archaeology Today is published by York Archaeological Trust. Editorial and contributors’ views are independent and do not necessarily reflect the official view of the Trust. Copyright of all original YAT material reserved; reproduction by prior editorial permission only. © York Archaeological Trust, May 2011 York Archaeological Trust is a registered charity, Charity No. 509060: A company limited by guarantee without share capital in England number 1430801. Tel: 01904 663000 Email: [email protected] http://www.yorkarchaeology.co.uk ISSN 1474-4562 Unless stated otherwise, illustrations are by Lesley Collett and Ian Milsted; photos are by Mike Andrews and members of YAT staff and are © York Archaeological Trust Cover Photos: Intaglios from Wellington Row, Coppergate and Hungate. -

Researching the Roman Collections of the Yorkshire Museum

Old Collections, New Questions: Researching the Roman Collections of the Yorkshire Museum Emily Tilley (ed.) 2018 Page 1 of 124 Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................. 5 1. Research Agenda .............................................................................................. 7 1.1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 8 1.2. Previous Research Projects ............................................................................ 9 1.3. Potential ......................................................................................................... 10 1.4. Organisations ................................................................................................. 12 1.5. Themes .......................................................................................................... 15 2. An Overview of the Roman Collections ......................................................... 21 2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 22 2.2. Summary of Provenance ............................................................................... 24 2.3. The Artefacts: Introduction ........................................................................... 25 2.4. Stone Monuments and Sculpture ................................................................ 26 2.5. Construction Materials ................................................................................. -

Artmap2mrch Copy

Bils & Rye 25 miles 9 The New School House Gallery - 10 The Fossgate Social - 25 Fossgate,York. 17 Peasholme Green, York. YO1 7PW. YO1 9TA. Mon-Fri 8.30am-12am, Tues - Sat 10am-5pm. Sat 9am-12am, Sun 10am-11pm. Paula Jackson and Robert Teed co-founded An independent coee bar with craft beer, lo The New School House Gallery in 2009. award winning speciality coee, a cute rd m Together they have curated over 30 exhibi- garden and a relaxed atmosphere. Hosting road 45 a te yo Kunsthuis 15 miles 18 a r huntington tions and projects across a range of monthly art exhibitions, from paintings b g s o y w o ll a and prints to grati, photography and th i lk disciplines and media. Since establishing river a g m the gallery, Jackson and Teed have been more; the Fossgate Social runs open mic P 1 3 nights for music, comedy, and the spoken footway developing a collaborative artistic practice 2 to complement their curatorial work. word. All events are free to perform, exhibit s t l and attend. bar walls e a schoolhousegallery.co.uk 4 o york minster n [email protected] thefossgatesocial.com a r P parking d [email protected] e s t p i 6 a l p g Kiosk Project Space - 41 Fossgate, et 11 i visitor information er m g a 12 Rogues Atelier - 28a Fossgate, Y019TA. r York. YO1 9TF. Tues - Sun 8am - 5pm. te 7 a a te d Open by appointment. eg o Open on occasion for evening events.