Fahrenheit 451, by Joseph Hurtgen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Decades of Science Fiction Quarter 4 – 2016 – Reading & Assignment Schedule Read Each Story with the Class And/Or on Your Own

Decades of Science Fiction Quarter 4 – 2016 – Reading & Assignment Schedule Read each story with the class and/or on your own. Write or type your short answers to the five Discussion Questions you will find at the end of each story. These are thoughtful, interpretive questions, so your answers will be original and unique. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ March 30: “The Disintegration Machine” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, pages 65-75 Due April 1 Doyle is the creator of the character Sherlock Holmes. Respond to Discussion Questions 1 through 5 on pages 75 & 76. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 1: “The Metal Man” by Jack Williamson, pages 78-87 Due April 5 Answer all five Discussion Questions on page 87. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 5: “Misfit” by Robert Heinlein, pages 119-137 Due April 7 Robert Heinlein is perhaps most well-known for his 1959 novel Starship Troopers. “Misfit” is also military science fiction. Discussion Questions 1 through 5 are on page 137. Answer them all. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ April 7: “Robbie” by Isaac Asimov, pages 149-165 Due April 11 “Robbie” is one of Asimov’s collected stories in I, Robot. Asimov created the “Three Laws of Robotics” in his extensive Robot series. “1. A Robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. 2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law. 3. A robot must protect its own existence, except where such protection would conflict with the First or Second Law.” Answer Discussion Questions 1, 2, 3, 4, & 5 on page 165. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Science Fiction List Literature 1

Science Fiction List Literature 1. “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” Edgar Allan Poe (1835, US, short story) 2. Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy (1888, US, novel) 3. A Princess of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1912, US, novel) 4. Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1915, US, novel) 5. “The Comet,” W.E.B. Du Bois (1920, US, short story) 6. Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury (1951, US, novel) 7. Limbo, Bernard Wolfe (1952, US, novel) 8. The Stars My Destination, Alfred Bester (1956, US, novel) 9. Venus Plus X, Theodore Sturgeon (1960, US, novel) 10. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Philip K. Dick (1968, US, novel) 11. The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin (1969, US, novel) 12. The Female Man, Joanna Russ (1975, US, novel) 13. “The Screwfly Solution,” “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” “The Women Men Don’t See,” “Houston, Houston Do You Read?”, James Tiptree Jr./Alice Sheldon (1977, 1973, 1973, 1976, US, novelettes, novella) 14. Native Tongue, Suzette Haden Elgin (1984, US, novel) 15. Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, Samuel R. Delany (1984, US, novel) 16. Neuromancer, William Gibson (1984, US-Canada, novel) 17. The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985, Canada, novel) 18. The Gilda Stories, Jewelle L. Gómez (1991, US, novel; extended edition 2016) 19. Dawn, Octavia E. Butler (1987, US, novel); Parable of the Sower, Butler (1993, US, novel); Bloodchild and Other Stories, Butler (1995, US, short stories; extended edition 2005) 20. Red Spider, White Web, Misha Nogha/Misha (1990, US, novel) 21. The Rag Doll Plagues, Alejandro Morales (1991, US, novel) 22. -

Read Jessica's Essay

Gateway Books: A Collection of My Childhood Favorites Jessica Cole (A20) By the time I turned 13, I had moved seven times. As I ping ponged from California to Indonesia, the one constant in my life were my books. And when we settled into our current home, our house was quickly weighed down with over 700 of our favorites, but the ones that were the most precious to me were my gateway books. Every avid reader has gateway books: books that stole them away and introduced them to the joys of reading. My gateway books stayed with me through all of the moving and packing and donating until I graduated. I moved across the country for college and my suitcase was, for the first time, bookless. Objectively I knew that it made sense to leave them behind, but their absence seemed louder than ever as I spent my first night alone in this strange new place. So in my sophomore year of college I began to look to search for books that I could keep with me, books that would make me feel at home. The first find was the illustrated complete set of the Chronicles of Narnia books that stayed with my family in California. It was out of print, but I managed to find an edition secondhand to keep with me. Every night for four years my father would come into my bedroom before bed. He would open up that large illustrated copy of Narnia by tugging on the red book mark, and then he would begin to read. -

Manuel De Pedrolo's "Mecanoscrit"

Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía Volume 4 Issue 2 Manuel de Pedrolo's "Typescript Article 3 of the Second Origin" Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor Pere Gallardo Torrano Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Other Spanish and Portuguese Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gallardo Torrano, Pere (2017) "Political Wishful Thinking versus the Shape of Things to Come: Manuel de Pedrolo’s "Mecanoscrit" and “Los últimos días” by Àlex and David Pastor," Alambique. Revista académica de ciencia ficción y fantasía / Jornal acadêmico de ficção científica e fantasía: Vol. 4 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. https://www.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/2167-6577.4.2.3 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/alambique/vol4/iss2/3 Authors retain copyright of their material under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License. Gallardo Torrano: Catalan Apocalypse: Pedrolo versus the Pastor Brothers The present Catalan cultural and linguistic revival is not a new phenomenon. Catalan language and culture is as old as the better-known Spanish/Castilian is, with which it has shared a part of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. The 19th century brought about a nationalist revival in many European states, and many stateless nations came into the limelight. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Anderson Entertainment

Anderson Entertainment Anderson Entertainment is the TV & Film production company of the late Gerry Anderson MBE - the man behind a huge number of cult sci-fi and adventure series like Fireball XL5, Stingray, Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet, UFO, Space:1999, Terrahawks, and Space Precinct among many others. Now headed by Anderson's son Jamie, the company continues to develop Gerry's unfinished film, TV and literary work, as well as maintaining his legacy. In October 2012 they completed a successful Kickstarter campaign to complete and publish Gerry's final series of novels: Gemini Force One. Agents Robert Kirby Associate Agent 0203 214 0800 Kate Walsh [email protected] 020 3214 0884 Publications Children's Publication Notes Details GEMINI FORCE Ben Carrington's dream has become a reality: he's finally a member of Gemini ONE: GHOST Force. But, still suffering from the deaths of his parents, it's a bitter-sweet MINE triumph. 2015 When news reaches GF1 of a gang of illegal 'ghost' miners trapped after a Orion South African mining disaster, Ben is glad to spring into action with the team. But it soon emerges that the company, Auron, doesn't want its miners found. Ben must work out who to trust if he's to ensure that Gemini Force pulls off its most difficult mission yet . Impossible rescues. Maximum risk. This is Gemini Force 1. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Notes Details GEMINI FORCE Impossible rescues - Maximum risk - Gemini Force 1 ONE: BLACK After the tragic death of his father, Ben Carrington's mother teams up with a HORIZON wealthy entrepreneur to form an elite, top-secret rescue organisation - Gemini 2015 Force. -

Medicine in Science Fiction

297 Summer 2011 Editors Doug Davis Gordon College 419 College Drive SFRA Barnesville, GA 30204 A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association [email protected] Jason Embry In this issue Georgia Gwinnett College SFRA Review Business 100 University Center Lane Global Science Fiction.................................................................................................................................2 Lawrenceville, GA 30043 SFRA Business [email protected] There’s No Place Like Home.....................................................................................................................2 Praise and Thanks.........................................................................................................................................4 Nonfiction Editor Conventions, Conferences, SFRA and You...............................................................................................4 ASLE-SFRA Affiliation Update....................................................................................................................5 Michael Klein Executive Committee Business................................................................................................................6 James Madison University MSC 2103 July 2011 Executive Committee Minutes...............................................................................................6 Harrisonburg, VA 22807 SFRA Business Meeting Minutes...........................................................................................................10 -

NVS 3-1-5 M-Perschon

Steam Wars Mike Perschon (Grant MacEwan University/University of Alberta, Canada) Abstract: While steampunk continues to defy definition, this article seeks to identify a coherent understanding of steampunk as an aesthetic. By comparing and contrasting well-known cultural icons of George Lucas’s Star Wars with their steampunk counterparts, insightful features of the steampunk aesthetic are suggested. This article engages in a close reading of individual artworks by digital artists who took part in a challenge issued on the forums of CGSociety (Computer Graphics Society) to apply a steampunk style to the Star Wars universe. The article focuses on three aspects of the steampunk aesthetic as revealed by this evidentiary approach: technofantasy, a nostalgic interpretation of imagined history, and a willingness to break nineteenth century gender roles and allow women to act as steampunk heroes. Keywords: CGSociety (Computer Graphics Society), digital art, gender roles, George Lucas, Orientalism, Star Wars , steampunk, technofantasy, visual aesthetic ***** It has been over twenty years since K.W. Jeter inadvertently coined the term ‘steampunk’ in a letter to Locus magazine in 1987. Jeter jokingly qualified the neo-Victorian writings he, James P. Blaylock, and Tim Powers were producing with the ‘-punk’ appendix, playing off the 1980s popularity of cyberpunk. Ironically the term stuck, both as descriptor for nearly every neo-Victorian work of speculative fiction since Jeter’s Infernal Devices (1987), while retroactively subsuming works such as Keith Roberts’s Pavane (1968), Michael Moorcock’s The Warlord of the Air (1971) , the 1960s television series Wild, Wild West (1965-1969, created by Michael Garrison), and even the writings of H.G. -

Posthumanism in Latin American Science Fiction Between 1960-1999

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2015 For the Love of Robots: Posthumanism in Latin American Science Fiction Between 1960-1999 Grace A. Martin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Martin, Grace A., "For the Love of Robots: Posthumanism in Latin American Science Fiction Between 1960-1999" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 21. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/21 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

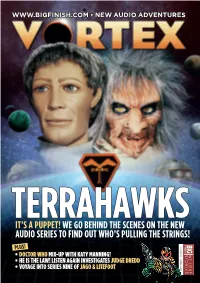

It's a Puppet! We Go Behind the Scenes on the New Audio Series to Find out Who's Pulling the Strings!

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES TERRAHAWKS IT’S A PUPPET! WE GO BEHIND THE SCENES ON THE NEW AUDIO SERIES TO FIND OUT WHO’S PULLING THE STRINGS! PLUS! • APRIL 2015 74 ISSUE • DOCTOR WHO MIX-UP WITH KATY MANNING! • HE IS THE LAW! LISTEN AGAIN INVESTIGATES JUDGE DREDD • VOYAGE INTO SERIES NINE OF JAGO & LITEFOOT WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio dramas and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a Survivors as well as classic characters such bonus release, downloadable audio readings of as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the new short stories and discounts. Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The www.bigfinish.com Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. You can access a video guide to the site at We publish a growing number of books (non- www.bigfinish.com/news/v/website-guide-1 fiction, novels and short stories) from new and established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial Charlotte Pollard: Series Two ASSUME that the majority of Big I Finish listeners are fans of cult TV and film and many of their friends Executive producer and writer share the same interest.