Resource Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

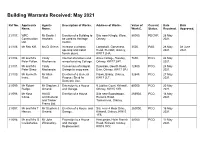

Building Warrants Received: May 2021

Building Warrants Received: May 2021 Ref No. Applicants Agents Description of Works. Address of Works. Value of Current Date Date Name. Name. Work £. Status. Received. Approved. 21/107. WRC Mr Bashir I Erection of a Building to Site near Kringlo, Wyre, 85000. RECNP. 28 May Construction Hasham. be used as Heritage Orkney. 2021. Ltd. Centre. 21/106. Mr Rob Kiff. Ms Di Grieve. Increase a window Langskaill, Gorseness 3500. PAS. 28 May 08 June opening and install Road, Rendall, Orkney, 2021. 2021. french doors. KW17 2HA. 21/104. Mr and Mrs Cindy Internal alterations and Alma Cottage, Sanday, 7600. PCO. 24 May Peter Fallon. Mackenzie. re-roof existing Cottage. Orkney, KW17 2AY. 2021. 21/101. Mr and Mrs Cindy Conversion of integral Dykeside, Georth Road, 12500. PCO. 24 May Peter Shaw. Mackenzie. Garage to snug area. Evie, Orkney, KW17 2PJ. 2021. 21/100. Mr Kenneth Mr Allan Erection of a General Flaws, Birsay, Orkney, 32848. PCO. 27 May Irvine. Reid. Purpose Shed for KW17 2LT. 2021. Domestic Use. 21/099. Mr Robert Mr Stephen J Extension to a House 9 Jubilee Court, Kirkwall, 80000. PCO. 20 May Budge. Omand. and Garage. Orkney, KW15 1XR. 2021. 21/098. Mr Ross HAUS Erection of a House. Site near Boondatoon, 266902. PCO. 18 May Corse. Architectural Rerwick Road, 2021. and Timber Tankerness, Orkney. Frame Ltd. 21/097. Mr and Mrs T Mr Stephen J Erection of a House and Site near 4 Moar Drive, 260000. PCO. 18 May Harcus. Omand. Garage. Kirkwall, Orkney, KW15 2021. 1FS. 21/096. Mr and Mrs G Mr John Extension to a House Hescombe, Holm Branch 30000. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Ferry Timetables

1768 Appendix 1. www.orkneyferries.co.uk GRAEMSAY AND HOY (MOANESS) EFFECTIVE FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2018 UNTIL 4 MAY 2019 Our service from Stromness to Hoy/Graemsay is a PASSENGER ONLY service. Vehicles can be carried by prior arrangement to Graemsay on the advertised cargo sailings. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Stromness dep 0745 0745 0745 0745 0745 0930 0930 Hoy (Moaness) dep 0810 0810 0810 0810 0810 1000 1000 Graemsay dep 0825 0825 0825 0825 0825 1015 1015 Stromness dep 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1030 1030 1030 1030 1030 Graemsay dep 1045 1045 1045 1045 1045 Stromness dep 1200A 1200A 1200A Graemsay dep 1230A 1230A 1230A Hoy (Moaness) dep 1240A 1240A 1240A Stromness dep 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 Graemsay dep 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 Stromness dep 1745 1745 1745 1745 1745 Graemsay dep 1800 1800 1800 1800 1800 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1815 1815 1815 1815 1815 Stromness dep 2130 Graemsay dep 2145 Hoy (Moaness) dep 2200 A Cargo Sailings will have limitations on passenger numbers therefore booking is advisable. These sailings may be delayed due to cargo operations. Notes: 1. All enquires must be made through the Kirkwall Office. Telephone: 01856 872044. 2. Passengers are requested to be available for boarding 5 minutes before departure. 3. Monday cargo to be booked by 1600hrs on previous Friday otherwise all cargo must be booked before 1600hrs the day before sailing. Cargo must be delivered to Stromness Pier no later than 1100hrs on the day of sailing. -

The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire

The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire: Archaeology, Design, Astronomy and Methods By John Hill The Recumbent Stone Circles of Aberdeenshire: Archaeology, Design, Astronomy and Methods By John Hill This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by John Hill All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6585-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6585-2 This book is dedicated to: Dr Joan J Taylor (1940-2019) Dr Aubrey Burl (1926-2020) “What was once considered on the fringe of archaeology, now becomes mainstream” and to Rocky (2009-2020) “My faithful companion who walked every step of the way with me across the Aberdeenshire landscape” TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................ ix List of Tables ............................................................................................ xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xiii Introduction ............................................................................................... -

The Holm of Papa Westray Stonework Survey 2018

HOLM OF PAPA WESTRAY SOUTH, PAPA WESTRAY, ORKNEY DECORATED INTERIOR STONEWORK SURVEY 2018 ANTONIA THOMAS 2019 Contents List of figures ......................................................................................................................... 3 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. 5 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................. 6 2.0 Site Description .......................................................................................................... 6 3.0 Archaeological Background ................................................................................... 8 3.1 Early accounts and investigations .................................................................................. 8 3.2 20th-century Guardianship, restoration, and survey work .................................... 9 3.3 Recent work and current state ........................................................................................ 11 4.0 Project Aims and Objectives ................................................................................. 13 4.1 Project Aims ........................................................................................................................... 13 4.2 Alignment to HES Corporate Plan 2016-2019 -

Megaliths and Stelae in the Inner Basin of Tagus River: Santiago De Alcántara, Alconétar and Cañamero (Cáceres, Spain)

MEGALITHS AND STELAE IN THE INNER BASIN OF TAGUS RIVER: SANTIAGO DE ALCÁNTARA, ALCONÉTAR AND CAÑAMERO (CÁCERES, SPAIN) Primitiva BUENO RAMIREZ, Rodrigo de BALBÍN BEHRMANN, Rosa BARROSO BERMEJO Área de Prehistoria de la Universidad de Alcalá de Henares Enrique CERRILLO CUENCA CSIC, Instituto de Arqueología de Mérida Antonio GONZALEZ CORDERO, Alicia PRADA GALLARDO Archaeologist Abstract: Several projects on the megalithic sites in the basin of the river Tagus contribute evidences on the close relation between stelae with engraved weapons and chronologically advanced megalithic graves. The importance of human images in the development of Iberian megalithic art supports an evolution of these contents toward pieces with engraved weapons which dating back to the 3rd millennium cal BC. From the analysis of the evidences reported by the whole geographical sector, this paper is also aimed at determining if the graphic resources used in these stelae express any kind of identity. Visible stelae in barrows and chambers from the 3rd millennium cal BC would be the images around which sepulchral areas were progressively added, thus constituting true ancestral references throughout the Bronze Age. Keywords: Chalcolithic, megalithic sites, identities, metallurgy, SW Iberian Peninsula INTRODUCTION individuals along a constant course (Bueno et al. 2007a, 2008a) from the ideology of the earliest farmers (Bueno The several works on megalithic stelae we have et al. 2007b) to, practically, the Iron Age (Bueno et al. developed so far shape a methodological and theoretical 2005a, 2010). The similarity observed between this long base of analysis aimed at proving a strong symbolic course and the line of megalithic art is the soundest implementation current throughout the 3rd millennium cal reference to include the symbolic universe of these BC in SW Iberian Peninsula (Bueno 1990, 1995: Bueno visible anthropomorphic references in the ideological et al. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE NEOLITHIC AND LATE IRON AGE POTTERY FROM POOL, SANDAY, ORKNEY An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Neolithic and Late Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses 2 Volumes Volume 1 Ann MACSWEEN submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeological Sciences University of Bradford 1990 ABSTRACT Ann MacSween The Neolithic and Late Iron Age Pottery from Pool, Sanday, Orkney: An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses Key Words: Neolithic; Iron Age; Orkney; pottery; X-ray Fluorescence; Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry; Petrological Analysis The Neolithic and late Iron Age pottery from the settlement site of Pool, Sanday, Orkney, was studied on two levels. Firstly, a morphological and tech- nological study was carried out to establish a se- quence for the site. Secondly an assessment was made of the usefulness of X-ray Fluorescence Analysis, In- ductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry and Petrological analysis to coarse ware studies, using the Pool assem- blage as a case study. Recording of technological and typological attributes allowed three phases of Neolithic pottery to be iden- tified. The earliest phase included sherds of Unstan Ware. -

The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney | 41

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 145 (2015), 41–89 THE KNOWE OF ROWIEGAR, ROUSAY, ORKNEY | 41 The Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney: description and dating of the human remains and context relative to neighbouring cairns Margaret Hutchison,* Neil Curtis* and Ray Kidd* ABSTRACT The Neolithic chambered cairn at Knowe of Rowiegar, Rousay, Orkney, was excavated in 1937 as part of a campaign that also saw excavations at sites such as Midhowe and the Knowe of Lairo. Not fully published at the time, and with only partial studies since, the human bone assemblage has now been largely re-united and investigated. This included an osteological study and AMS dating of selected bones from this site and other Rousay cairns in the care of University of Aberdeen Museums, as well as the use of archival sources to attempt a reconstruction of the site. It is suggested that the human remains were finally deposited as disarticulated bones and that the site was severely damaged at the time the adjacent Iron Age souterrain was constructed. The estimation of the minimum number of individuals represented in the assemblage showed a significant preponderance of crania and mandibles, suggesting the presence of at least 28 heads, along with much smaller numbers of other bones, while age and sex determinations showed a preponderance of adult males. Seven skulls showed evidence of violent trauma, while evidence from both bones and teeth indicates that there were high levels of childhood dietary deficiency. Although detailed analysis of the dates was hampered by the ‘Neolithic plateau’, a Bayesian analysis of the radiocarbon determinations suggests the use of the site during the period 3400 to 2900 cal BC. -

Excavations of a Medieval Cemetery at Skaill House, and a Cist in the Bay of Skaill, Sandwick, Orkney

Proc Soc Antic/ Scot, 129 (1999), 753-777 Excavation medievaa f so l cemeter t Skailya l Housed an , a cist in the Bay of Skaill, Sandwick, Orkney Heather F James* with contribution LorimeH D RobertJ y sb r& s ABSTRACT A medieval cemetery structuraland remains were discovered during drainage works Skaillat House, Sandwick, Orkney. Several skeletons were salvaged Orkneythe by Islands Archaeologist laterand excavations by GUARD revealed further cisted burials. These have been radiocarbon dated to between llth14th the Skaillof and upper centuries.the Bay cisteda half the of At burialwas salvaged been afterhad it exposed effects the coastalof by erosion. radiocarbonA date fromthe bone shows that burialthe belongs sevenththe to century StructuralAD. elementspre-dating cistthe were also eroding seenthe in cliff-face, theseand were probably prehistoric. excavationThe and publication were funded Historicby Scotland. INTRODUCTION In October 1996, while monitoring the digging of a new drainage and waste water disposal system around Skaill House, Sandwick, Orkney (NGR: HY 2346 1860), Raymond Lamb, Orkney Islands Archaeologist s e discoveralerteth wa , o t d f humao y n remains withi e drainagnth e construction trench. Assisted by Julie Gibson, Historic Scotland Field Warden, he undertook salvage excavation skeletone th f so s whic beed hha n disturbed pipe Th .e trenc expandes hwa n di orde excavato rt removd ean buriae eon l whose skul withiy lla nstona e box. recognizes wa t I d tha remaine tth s were unforesee proposale th drainag e y nth b r sfo e works werd an e potentially importan understandine th o t t Skaillf archaeologo e y th n f ,Ba a go e th f yo area ric prehistorin hi medievad can l remains, includin renownee gth d prehistoric villag Skarf eo a Brae Raymons .A d Lamb' t havs resourceoffice no eth d edi completo st excavationse eth , Historic Scotland agree mako dt e funds availabl investigatioe th r efo recordind nan furthef go r skeletons which were likel encounterede b yo t Novembern I .