CHAPTER ONE WUNAMBAL PEOPLE and THEIR LANGUAGE 1.1 Location Wunambal Is an Australian Language Traditionally Spoken in the Most

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Condition Report Issued Saturday 23 November 2019 1250Hrs

S H I R E o f W Y N D H A M E A S T K I M B E R L E Y Road Condition Report Issued Saturday 23 November 2019 1250hrs PO Box 614 Kununurra 6743 Caution must be exercised at all times. 20 Coolibah Drive KUNUNURRA Flood ways and creek crossings may rise without notice; depths should be checked before crossing. The below information will be updated as conditions change. Koolama Street WYNDHAM Further information can be found on: T | 9168 4100 F Wyndham and the East Kimberley Shire roads 08 9168 4100 or www.swek.wa.gov.au | 9168 1798 E Derby and West Kimberley Shire roads 08 9191 0999 or www.sdwk.wa.gov.au | [email protected] W | www.swek.wa.gov.au Department of Parks and Wildlife (DPAW) Access Roads 08 9168 4200 Western Australia highways and the Gibb River Road contact Main Roads WA 138 138 Northern Territory roads 1800 246 199 or http://www.ntlis.nt.gov.au/roadreport 8.00am - 4.00pm MON - FRI KUNUNURRA TOWNSHIP WEABER PLAIN ROAD Intersection with Barringtonia Avenue OPEN Section between Mills Road and Mulligans OPEN Lagoon Road Unsealed section from Carlton Hill Road to the OPEN end of Weaber Plain Road RESEARCH STATION ROAD Ivanhoe Road to Stock Route Road OPEN WYNDHAM TOWNSHIP No roads currently listed KALUMBURU ROAD Gibb River Road/ Kalumburu Road junction to OPEN Drysdale River Station Drysdale River Station to Kalumburu Road/ Port OPEN Warrender Road Junction Kalumburu Road/ Port Warrender Road Junction OPEN to Kalumburu PORT WARRENDER ROAD (INCLUDES MITCHELL PLATEAU/FALLS) Kalumburu Road/ Port Warrender Road Junction to OPEN -

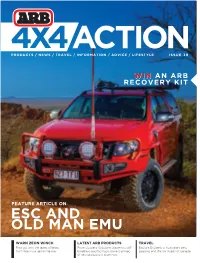

ESC and Old Man Emu

AI CT ON PRODUCTS / NEWS / TRAVEL / INFORMATION / ADVICE / LIFESTYLE ISS9 UE 3 W IN AN ARB RECOVERY KIT FEATURE ARTICLE ON ESC AND OLD MAN EMU WARN ZEON WINCH LATEST ARB PRODUCTS TRAVEL Find out why the latest offering From Outback Solutions drawers to diff Explore El Questro, Australia’s best from Warn is a game changer breathers and flip flops, there is a heap beaches and the Ice Roads of Canada of new products in store now CONTENTS PRODUCTS COMPETITIONS & PROMOTIONS 4 ARB Intensity LED Driving Light Covers 5 Win An ARB Back Pack 16 Old Man Emu & ESC Compatibility 12 ARB Roof Rack With Free 23 ARB Differential Breather Kit Awning Promotion 26 ARB Deluxe Bull Bar for Jeep WK2 24 Win an ARB Recovery Kit Grand Cherokee 83 On The Track Photo Competition 27 ARB Full Extension Fridge Slide 32 Warn Zeon Winch 44 Redarc In-Vehicle Chargers 45 ARB Cab Roof Racks For Isuzu D-Max REGULARS & Holden Colorado 52 Outback Solutions Drawers 14 Driving Tips & Techniques 54 Latest Hayman Reese Products 21 Subscribe To ARB 60 Tyrepliers 46 ARB Kids 61 Bushranger Max Air III Compressor 50 Behind The Shot 66 Latest Thule Accessories 62 Photography How To 74 Hema HN7 Navigator 82 ARB 24V Twin Motor Portable Compressor ARB 4X4 ACTION Is AlsO AvAIlABlE As A TRAVEL & EVENTS FREE APP ON YOUR IPAD OR ANDROID TABLET. 6 Life’s A Beach, QLD BACk IssuEs CAN AlsO BE 25 Rough Stuff, Australia dOwNlOAdEd fOR fREE. 28 Ice Road, Canada 38 Water For Africa, Tanzania 56 The Eastern Kimberley, WA Editor: Kelly Teitzel 68 Emigrant Trail, USA Contributors: Andrew Bellamy, Sam Boden, Pat Callinan, Cassandra Carbone, Chris Collard, Ken Duncan, Michael Ellem, Steve Fraser, Matt 76 ARB Eldee Easter 4WD Event, NSW Frost, Rebecca Goulding, Ron Moon, Viv Moon, Mark de Prinse, Carlisle 78 Gunbarrel Hwy, WA Rogers, Steve Sampson, Luke Watson, Jessica Vigar. -

The Growing Presence of Inauthentic Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Dear Please take this email as being KALACC’s Submission to the inquiry into the proliferation of inauthentic Aboriginal 'style' art We do understand perfectly well that the matters raised in this submission lie somewhat outside of the terms of reference for the Inquiry. But we feel that they are important matters worthy of consideration by the Committee. Essentially our submission to the Committee relates to the use, by both Indigenous and non – Indigenous people, of the Wandjina image. From a Western, European perspective, the Kimberley Aboriginal Law and Culture Centre holds a Trademark over the Wandjina. Trademark documents are attached. From an Aboriginal perspective, KALACC represents the interests of the cultural custodians and law bosses for the 30 language groups of the Kimberley, including the north – Kimberley groups for which the Wandjina is the key to their spirituality and traditional law and culture. From that perspective, only ‘authorised’ persons can use ie can artistically represent the Wandjina figure. Such permission or authorization will only ever be granted to members of those three language groups and even then only to selected individuals who are considered by the cultural bosses to be ‘appropriate’ persons to represent the Wandjina. Sadly, the Western European law ie the Trademark affords us limited protections against unauthorized use of the Wadjina. And certain individuals within the wider public are only too willing to disregard Aboriginal law and the wishes of the cultural custodians. This thing has a very -

13 Day Kimberley Explorer

LE ER Y W B I M L I D K 2021 Trip Notes 13 DAY KIMBERLEY EXPLORER system carved through the Napier Range, Days 9-10 Purnululu National Itinerary we discover stalactites, secret caves and Park: Bungle Bungles Day 1 Beagle Bay, One Arm Point a large variety of wildlife. It is here we also After a leisurely morning, head south & the Buccaneer Archipelago learn the legend of Jandamarra, an down the Great Northern Highway to Aboriginal freedom fighter who used the The Dampier Peninsula is an extraordinary Purnululu National Park, home of the tunnel as a hide-out in the late 1800’s. blend of pristine beaches and dramatic magnificent Bungle Bungles. Two nights Don’t miss a refreshing swim in an idyllic coastlines, rich in traditional Aboriginal here, staying in our private Bungle Bungle waterhole. That night we settle into our first culture. Travelling up the red 4WD track, Safari Camp in the heart of the Park, night under the Kimberley night sky. (BLD) learn about the region’s fascinating history allows a full day to explore the from our guided commentary. Our first Days 4-5 West Kimberley Gorges highlights of this extraordinary National stop is the Beagle Bay Aboriginal Commu- The Napier Range is over 350 million years Park, the most famous of which, are the nity, home of the Beagle Bay Church with old and home to the geological wonder of Bungle Bungle domes. Rivers created this its glimmering pearl shell altar, for morning Windjana Gorge. Beneath gorge walls landscape of unique orange and black tea. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

On Numeral Complexity in Hunter-Gatherer Languages

On numeral complexity in hunter-gatherer languages PATIENCE EPPS, CLAIRE BOWERN, CYNTHIA A. HANSEN, JANE H. HILL, and JASON ZENTZ Abstract Numerals vary extensively across the world’s languages, ranging from no pre- cise numeral terms to practically infinite limits. Particularly of interest is the category of “small” or low-limit numeral systems; these are often associated with hunter-gatherer groups, but this connection has not yet been demonstrated by a systematic study. Here we present the results of a wide-scale survey of hunter-gatherer numerals. We compare these to agriculturalist languages in the same regions, and consider them against the broader typological backdrop of contemporary numeral systems in the world’s languages. We find that cor- relations with subsistence pattern are relatively weak, but that numeral trends are clearly areal. Keywords: borrowing, hunter-gatherers, linguistic area, number systems, nu- merals 1. Introduction Numerals are intriguing as a linguistic category: they are lexical elements on the one hand, but on the other they are effectively grammatical in that they may involve a generative system to derive higher values, and they interact with grammatical systems of quantification. Numeral systems are particularly note- worthy for their considerable crosslinguistic variation, such that languages may range from having no precise numeral terms at all to having systems whose limits are practically infinite. As Andersen (2005: 26) points out, numerals are thus a “liminal” linguistic category that is subject to cultural elaboration. Recent work has called attention to this variation among numeral systems, particularly with reference to systems having very low limits (for example, see Evans & Levinson 2009, D. -

Welch, Aboriginal Paintings at Munurru

berley region o alth of Aboriginal .....ll.Lll. ,_,., ..·,,.tors with their first ' ABORIGINAL PAINTINGS ATMUNURRU KIMBERLEY, WESTERN AUSTRALIA Jonathon Goonack, William Bunjuk and Wilfred Goonack at Bunjamanamanu, the main Wandjina site of Munurru. 2000. CONTENTS Introduction 1 Kimberley rock art styles 3 The Wandjina Complex at Munurru 15 The Warnmarri. (Brolga) Complex at Munurru 41 Weathering and human impact on the Munurru sites 67 Further reading 74 ~ . '?".! ,:.. ; - ·.-.. ~,. ~ i,~,-~ . - .,. • ~_,. A'>'' • ~ ~t~ ~~ _,. ?:.t ~ ::ii:;; . ~-~-L.·) • .. ;>'-< ~- l INTRODUCTION WO clusters of rock outcrops near the King Edward River Crossing on the track to the Mitchell Plateau in the far north of Western T Australia provide visitors with access to Kimberley Aboriginal rock paintings. The Wunambal people know this area as Munurru, the borderland between their tribe (language group) and that of the Ngarinyin people to the east of Mungara (also written Mungurra), the King Edward River. Today, Wunambal people live at Kandiwal and Kalumburu to the north, and around Derby to the west. In 2000 I led a group of international rock art experts to visit these and other Kimberley rock shelters, and we were privileged to accompany traditional owners William Bunjuk, Wilfred Goonack, and Jonathon Goonack to the sites. According to their legends, the Wandjina (known here as Gulingi) carried these boulders to the area and then lay down to rest, creating their self-images as the Wandjina paintings. The first rock cluster is located 700 metres after crossing the King Edward River heading westward, and the second cluster is approximately Mungara (the King Edward River) borders Wunambal and Ngarinyin lands. -

Prosodic Aspects of Warrwa Narratives

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/292421848 Prosodic Aspects of Warrwa Narratives Thesis · November 2006 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.1.5082.9841 CITATIONS READS 0 368 1 author: Bella Ross Monash College 56 PUBLICATIONS 400 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: E-texts versus texts: Developing pedagogical practice View project Critical approaches to educational technologies View project All content following this page was uploaded by Bella Ross on 31 January 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Prosodic Aspects of Warrwa Narratives Prosodiske aspekter ved narrativer på Warrwa Belinda Ross Student number: 20043062 Supervisor: William McGregor Afdeling for Lingvistik, Aarhus Universitet 2006 138,350 characters (with spaces) Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................3 Abstrakt...............................................................................................................4 1 Preliminaries.....................................................................................................5 1.1 Aims of this Study......................................................................................5 1.2 Warrwa......................................................................................................6 1.3 Narratology................................................................................................9 -

Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal Languages South of the Kimberley Region

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - 124 HANDBOOK OF WESTERN AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES SOUTH OF THE KIMBERLEY REGION Nicholas Thieberger Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Thieberger, N. Handbook of Western Australian Aboriginal languages south of the Kimberley Region. C-124, viii + 416 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1993. DOI:10.15144/PL-C124.cover ©1993 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES c: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender KA. McElhanon University of Hawaii Summer Institute of Linguistics DavidBradley H.P. McKaughan La Trobe University University of Hawaii Michael G. Clyne P. Miihlhausler Monash University University of Adelaide S.H. Elbert G.N. O'Grady University of Hawaii University of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Franklin KL. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W.Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K T' sou Harvard University City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. -

Nyikina Paradigms and Refunctionalization: a Cautionary Tale in Morphological Reconstruction

Nyikina Paradigms and Refunctionalization: A Cautionary Tale in Morphological Reconstruction Claire Bowern Yale University Department of Linguistics PO Box 208366 New Haven, CT 06520, USA [email protected] Ph: +1.203.432.2045 Keywords: morphology, Nyulnyulan, Australian languages, exaptation, reconstruction, analogy 1 Abstract Here I present a case study of change in the complex verb morphology of the Nyikina language of Northwestern Australia. I describe changes which lead to reanalysis of underlying forms while preserving much of the inherited phonological material. The changes presented here do not fit into previous typologies of morphological change. Nyikina lost the distinction between past and present, and in doing so, merged two paradigms into one. The former past tense marker came to be associated with intransitive verb stems. The inflected verbs thus continue inherited material, but in a different function. These changes are most parsimoniously described in a theory of word formation which makes reference to paradigms. 1 Introduction 1.1 Background Many types of change can occur in morphology. Studies such as Anderson (1988) and Koch (1996) identified a series of processes which cause change in morphemes. These include, in addition to regular sound change which operates on fully inflected forms, various types of boundary shift (such as the absorption of material into stems or the reanalysis of one morpheme as two), and analogical changes such as paradigm regularization. Inflectional material can also be lost. Other processes are particularly associated with morphological change in complex paradigms, though by no means exclusively so. These include so-called “hermit-crab” morphology – and the related change of “lost wax” – described by Heath (1997, 1998). -

Kimberley Language Resource Centre Submission to the Senate

Kimberley Language Resource Centre ABN: 43 634 659 269 PMB 11 HALLS CREEK WA 6770 phone: (08) 9168 6005 fax: (08) 9168 6023 [email protected] SUBMISSION TO THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER AFFAIRS FOR THE INQUIRY ON LANGUAGE LEARNING IN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES AUGUST 2011 KLRC SUBMISSION ON LANGUAGE LEARING IN INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES AUGUST 2011 This document remains the Intellectual Property of the organisation 1 ABOUT THE KIMBERLEY LANGUAGE RESOURCE CENTRE MISSION STATEMENT To advocate for Kimberley languages on all levels To promote recognition that diversity in languages is central to Kimberley culture, land and identity and that Aboriginal languages have value in today’s world. To work in partnership with the diverse Kimberley language communities To ensure Kimberley languages are passed on to children. The KLRC is the only organisation in Australia focussing solely on Kimberley Aboriginal languages. The Kimberley was, and still is, the one of the most linguistically diverse areas in Australia with at least 421 language groups plus additional dialects identified. The KLRC Directors advocate for the 30 or so languages still spoken. The organisation was established in 1984 by Aboriginal people concerned about the effects of colonisation and the continuing impact of Western society on their spoken languages and cultural knowledge. It is beginning its 26th year of operations with a wealth of experience and resources underpinning its service delivery. The organisation is governed by a Board of 12 Directors accountable to a membership from across the region. The office is based in Halls Creek in the East Kimberley. The KLRC provides a forum for developing language policy to strategically revive and maintain (in other words, continue) the Kimberley Aboriginal languages. -

Sea Countries of the North-West: Literature Review on Indigenous

SEA COUNTRIES OF THE NORTH-WEST Literature review on Indigenous connection to and uses of the North West Marine Region Prepared by Dr Dermot Smyth Smyth and Bahrdt Consultants For the National Oceans Office Branch, Marine Division, Australian Government Department of the Environment and Water Resources * July 2007 * The title of the Department was changed to Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts in late 2007. SEA COUNTRIES OF THE NORTH-WEST © Commonwealth of Australia 2007. This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Attorney General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 or posted at http://www.ag.gov.au/cca Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts or the Minister for Climate Change and Water. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication.