Eeing Ou Le Tories Fro the Heater of Ractice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Aboutthepennmuseum

NEWS RELEASE Pam Kosty, Public Relations Director 215.898.4045 [email protected] ABOUT THE PENN MUSEUM Founded in 1887, the Penn Museum (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) is an internationally renowned museum and research institution dedicated to the understanding of cultural diversity and the exploration of the history of humankind. In its 130-year history, the Penn Museum has sent more than 350 research expeditions around the world and collected nearly one million obJects, many obtained directly through its own excavations or anthropological and ethnographic research. Art and Artifacts from across Continents and throughout Time Three gallery floors feature art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, North and Central America, Asia, Africa, and the ancient Mediterranean World. Special exhibitions drawn both from the Museum’s own collections and brought in on loan enrich the gallery offerings. Ancient Egyptian treasures on display include monumental architectural elements from the Palace of Merenptah, mummies, and a 15-ton granite Sphinx—the largest Sphinx in the Western Hemisphere. Canaan and Ancient Israel features Near East artifacts and looks at the crossroads of cultures in that dynamic region. Worlds Intertwined, a suite of ancient Mediterranean World galleries, features more than 1,400 artifacts from Greece, Etruscan Italy, and the Roman world. The Museum’s Africa Gallery features material from throughout that vast continent, including fine West and Central African masks and instruments and an acclaimed Benin bronze collection from Nigeria, while an adJacent Imagine Africa with the Penn Museum proJect invites visitors to share perspectives and make suggestions for future African exhibitions. -

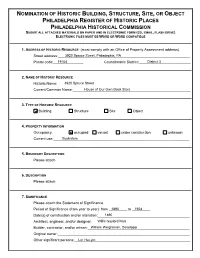

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3920 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3920 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:________House___________________________________________________ of Our Own Book Store 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Bookstore ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1924 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________ -

To Center City: the Evolution of the Neighborhood of the Historicalsociety of Pennsylvania

From "Frontier"to Center City: The Evolution of the Neighborhood of the HistoricalSociety of Pennsylvania THE HISToRICAL SOcIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA found its permanent home at 13th and Locust Streets in Philadelphia nearly 120 years ago. Prior to that time it had found temporary asylum in neighborhoods to the east, most in close proximity to the homes of its members, near landmarks such as the Old State House, and often within the bosom of such venerable organizations as the American Philosophical Society and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia. As its collections grew, however, HSP sought ever larger quarters and, inevitably, moved westward.' Its last temporary home was the so-called Picture House on the grounds of the Pennsylvania Hospital in the 800 block of Spruce Street. Constructed in 1816-17 to exhibit Benjamin West's large painting, Christ Healing the Sick, the building was leased to the Society for ten years. The Society needed not only to renovate the building for its own purposes but was required by a city ordinance to modify the existing structure to permit the widening of the street. Research by Jeffrey A. Cohen concludes that the Picture House's Gothic facade was the work of Philadelphia carpenter Samuel Webb. Its pointed windows and crenellations might have seemed appropriate to the Gothic darkness of the West painting, but West himself characterized the building as a "misapplication of Gothic Architecture to a Place where the Refinement of Science is to be inculcated, and which, in my humble opinion ought to have been founded on those dear and self-evident Principles adopted by the Greeks." Though West went so far as to make plans for 'The early history of the Historical Soiety of Pennsylvania is summarized in J.Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, Hisiory ofPhiladelphia; 1609-1884 (2vols., Philadelphia, 1884), 2:1219-22. -

Frank Miles Day, 1861-1918

THE ARCHITECTURAL ARCHIVES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA FRANK MILES DAY COLLECTION (Collection 059) Frank Miles Day, 1861-1918 A Finding Aid for Architectural Records and Personal Papers, 1882-1927 in The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania © 2002 The Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania Frank Miles Day Collection Finding Aid Archival Description Descriptive Summary Title: Architectural Records and Personal Papers, 1882-1927. Coll. ID: 059 Origin: Frank Miles Day, 1861-1918, architect. Extent: Project drawings: 111 architectural drawings (96 originals, 15 prints) Student drawings: 29 drawings Sketches: 106 travel sketches and 17 sketchbooks Photographs: 112 photoprints. Boxed files: 11 cubic feet. Repository: The Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania 102 Meyerson Hall Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-6311 (215) 898-8323 Abstract: This collection comprises project-related architectural drawings, student drawings, travel sketches, correspondence, personal financial materials, notes, lectures, books, photographs, memorabilia and materials related to Day's estate. Additional materials related to Day's professional practice are found in the Day and Klauder Collection (Collection #069). Indexes: This collection is included in the Philadelphia Architects and Buildings Project, a searchable database of architectural research materials related to architects and architecture in Philadelphia and surrounding regions: http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab Cataloging: Collection-level records for materials in the Architectural Archives may be found in RLIN Eureka, the union catalogue of members of the Research Libraries Group. The record number for this collection is PAUP01-A22. Publications: Keebler, Patricia Heintzelman. “The Life and Work of Frank Miles Day.” Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 1980. -

Nomination of Historic District Philadelphia Register of Historic Places Philadelphia Historical Commission

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC DISTRICT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. NAME OF HISTORIC DISTRICT ______________________________________________________________________Carnegie Library Thematic Historic District 2. LOCATION Please attach a map of Philadelphia locating the historic district. Councilmanic District(s):_______________various 3. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach a map of the district and a written description of the boundary. 4. DESCRIPTION Please attach a description of built and natural environments in the district. 5. INVENTORY Please attach an inventory of the district with an entry for every property. All street addresses must coincide with official Office of Property Assessment addresses. Total number of properties in district:_______________20 Count buildings with multiple units as one. Number of properties already on Register/percentage of total:______11 __/________55% Number of significant properties/percentage of total:____________/___________ Number of contributing properties/percentage of total:___________/____________20 100% Number of non-contributing properties/percentage of total:_______/____________ 6. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1905 to _________1930 CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic district satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, -

What Was There Before the by Ann Blair Brownlee

Museum?What Was There Before the by ann blair brownlee It was a “wretched stretch of land” according to Dr. William Pepper’s biography. “One gray March day, in 1894, Dr. Pepper and Mrs. Stevenson [another early and important supporter of the Museum and later curator of the Mediterranean and Egyptian sections], with Mr. Justus C. Strawbridge, whom they were anxious to interest in the project, and to whom they wished to show the new land, met by appointment at the end of South Street bridge. A strong east wind blew from the river, and the whole outlook was hopelessly dismal. Mr. Strawbridge stood looking over the dreary waste, whilst Dr. Pepper enthusiastically explained the glorious possibilities offered to his view by the wretched stretch of land before them. With each passing train a dense black smoke rolled up in sooty masses, enveloping railroad tracks, goats, and refuse in a black mist, whilst blasts of coal gas smothered the lungs of the visitors. Mr. Strawbridge gravely listened to Dr. Pepper’s vivid description. He even nodded in courteous approval as the complete plan, at an estimated cost of over two mil- lions of dollars, was explained to him; but his face wore a perplexed expression. As Dr. Pepper turned away for a moment to call the attention of a passing policeman to trespassers, Mr. Strawbridge whispered to his companion: ‘I cannot bear to throw cold water on Dr. Pepper’s enthusiasm; but what an extraordinary site for a great museum! Of course, I would like to help him; but what a site!’” (pp. -

The MITCHELLS and DAYS of PHILADELPHIA with Their Kin=

The MITCHELLS and DAYS of PHILADELPHIA With Their Kin= Dr. S. Weir Mitchell and Helena Mary Langdon (Mitchell) and Kenneth Mackenzie Day George Valentine Massey II Copyright 1968 by George Valentine Massey II Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 68-58728 Published by Irene A. Hermann Litho Co. 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, N. Y. Printed in the U.S.A. Table of UJntents Chapter I Page Day Family ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 1 Chapter II Miles Family ____ ---------------------------------------------- ___________________________ _ 19 Chapter III Kyn-Keen Family __________________________________ ------------------------------------ 29 Chapter IV Blakiston Family -------------------------------------------------------------------- 41 ' Chapter V Mitchell Family _______________ ,__ :_____________________________________________________ _ 53 Chapter VI Elwyn Family----------------------------------------------------------·-------··--·--- 83 Chapter VII Langdon-Dudley - Hall - Sherburne Families·····---·-·-···-·-·· 91 Chap_ter VIII Mease Family--------------·-·-···-·-·---·-·-···-·---·-·-·---------···-··------···-·--· 109 Chapter IX Butler Family--·--·--------··-·--···-____________________________________________________ 121 Chapter X Middleton and Bull Families ----·------------------------------------------- 139 Chapter XI Amory Family ------------·-----------------------------------------------------··-··--- 155 Chapter XII Lea and Robeson Families ---··-··--·-·-·····-----·-··-------·-------·-------- -

St. Peter's Episcopal Church National Register Form Size

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name St. Peter’s Episcopal Church other names/site number N/A 2. Location street & number 1 South Tschirgi N/A not for publication city or town Sheridan N/A vicinity state Wyoming code WY county Sheridan code 033 zip code 82801 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property x_ meets _ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide x local Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. -

4501, 4503, 4505, and 4507 Spruce St

ADDRESS: 4501, 4503, 4505, AND 4507 SPRUCE ST Proposed Action: Designation Property Owners: Bryce and Samantha McNamee (4501); Jessica Senker and Brian Donlen (4503); Sadequa Dadabhoy (4505); Joseph Marchaman (4507) Nominator: University City Historical Society Staff Contact: Megan Cross Schmitt, [email protected], 215-686-7660 OVERVIEW: This nomination proposes to designate the properties at 4501, 4503, 4505, and 4507 Spruce Street and list them on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. The nomination contends that the buildings satisfy Criteria for Designation A, D, and E. Under Criterion A, the nomination argues that the properties are significant for their association with Charles Mosley Swain, a prominent Philadelphia businessman and the land owner who constructed the row of buildings to galvanize development in West Philadelphia. Under Criteria D and E, the nomination contends that the row of buildings were designed in the Tudor Revival style, with characteristic half-timber framing and steeply pitched roofs, by one of Philadelphia’s best known architects, Wilson Eyre. STAFF RECOMMENDATION: The staff recommends that the nomination demonstrates that the properties at 4501, 4503, 4505, and 4507 Spruce Street satisfy Criteria for Designation A, D, and E. 4505 4501 4507 4503 (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:________________________4505 Spruce Street __________________________________________ Postal code:_______________19143 Historic Name:___________ _______________________________________________________ -

Times and Places

Times and Places Yet to walk with Mozart, Agassiz and Linnaeus 'neath overhanging air, under sun-beat Here take they mind's spa.ce. Ezra Pound, Class of 1906 Canto CXIII [overleaf] Main Reading Room, Furness Library, circa 1890 The lofty reading room, four stories high and deriving its inspiration from Viollet-le-Duc, was at the heart of Frank Furness' design to house the University Library. The open space, later divided up by obtrusive additions, was well lighted from above and around the upper walls. In a novel arrangement for the time, the book stacks were set apart in a separate unit. 199 16 A Campus Evolves In his analysis of the relation between biography and history, Roy F. Nichols emphasized the importance of understanding the physical surroundings both as a backdrop ~d as an active element which molds the individual personality. It is in the setting of the University that these portraits of scholars and leaders from the last two hundred years have been presented, and their lives and endeavors thus provide a commentary on the various stages of its changing history. In addition, the personality of the University itself is expressed in its physical character while continuously reflecting the evolution of its programs and aspirations. It is as impossible to do justice to each building or plan which has contributed to the changing surroundings as it is to comprehend an entire era or even one branch of academic life through reference to a few of the persons of stature who have graced the intellectual community at various times in the course of our history. -

A Legacy of Leadership the Presidents of the American Institute of Architects 1857–2007

A Legacy of Leadership The Presidents of the American Institute of Architects 1857–2007 R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA with Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA, and Andrew Brodie Smith THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS | WASHINGTON, D.C. The American Institute of Architects 1735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20006 www.aia.org ©2008 The American Institute of Architects All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-57165-021-4 Book Design: Zamore Design This book is printed on paper that contains recycled content to suppurt a sustainable world. Contents FOREWORD Marshall E. Purnell, FAIA . i 20. D. Everett Waid, FAIA . .58 21. Milton Bennett Medary Jr., FAIA . 60 PREFACE R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA . .ii 22. Charles Herrick Hammond, FAIA . 63 INTRODUCTION Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA . 1 23. Robert D. Kohn, FAIA . 65 1. Richard Upjohn, FAIA . .10 24. Ernest John Russell, FAIA . 67 2. Thomas U. Walter, FAIA . .13 25. Stephen Francis Voorhees, FAIA . 69 3. Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA . 16 26. Charles Donagh Maginnis, FAIA . 71 4. Edward H. Kendall, FAIA . 19 27. George Edwin Bergstrom, FAIA . .73 5. Daniel H. Burnham, FAIA . 20 28. Richmond H. Shreve, FAIA . 76 6. George Brown Post, FAIA . .24 29. Raymond J. Ashton, FAIA . .78 7. Henry Van Brunt, FAIA . 27 30. James R. Edmunds Jr., FAIA . 80 8. Robert S. Peabody, FAIA . 29 31. Douglas William Orr, FAIA . 82 9. Charles F. McKim, FAIA . .32 32. Ralph T. Walker, FAIA . .85 10. William S. Eames, FAIA . .35 33. A. Glenn Stanton, FAIA . 88 11. -

Architectural Ceramics in Philadelphia

ARCHITECTURAL CERAMICS IN PHILADELPHIA A Center City Walking Tour with Vance A. Koehler June 13, 2015 A fundraising activity for the Preservation Alliance ______________________________ 1. PHILADELPHIA CITY HALL 2. ONE EAST PENN SQUARE BUILDING 3. WITHERSPOON BUILDING 4. JACOB REED’S SONS STORE BUILDING 5. CROZER BUILDING 6. THE RACQUET CLUB 7. FOUNTAIN, RITTENHOUSE SQUARE 8. CHURCH OF THE HOLY TRINITY 9. RESIDENCE, 2034 LOCUST ST. 10. VENEZ VOIR BUILDING 11. RESIDENCE, 244 S. 21ST ST. 12. MARCEL VITI HOUSE 13. PHILADELPHIA ART ALLIANCE PHILADELPHIA CITY HALL 2 Broad and Market Streets City Hall was designed by Philadelphia architect John McArthur, Jr., with Thomas U. Walter, and built 1871-1901. It is recognized as one of the best and most impressive examples of Second Empire style architecture in the country. In 1973, John Maass wrote, “The building has . been regarded as a marvel of the age, as an obsolete relic, as a grotesque monstrosity, as a period piece of quaint charm, and now as a masterpiece of American architecture.” Tiles can be found in the pavements of the covered walkways leading into the large open courtyard on the exterior ground floor. Walk through the arched portals leading in from North Broad Street, South Broad Street or East Market Street and you will see running borders of encaustic tiles in geometric patterns of cream, blue, red, brown and buff. The tiles were made in Germany circa 1880-1900 by Villeroy and Boch, Mettlach, and by Mosaic Fabrik in Sinzig-am-Rhein. This type of tile was commonly used throughout public buildings in the area, although most are now gone.