© 2013 Henrietta F. Sablove ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspective on Canaletto's Paintings of Piazza San Marco in Venice

Art & Perception 8 (2020) 49–67 Perspective on Canaletto’s Paintings of Piazza San Marco in Venice Casper J. Erkelens Experimental Psychology, Helmholtz Institute, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands Received 21 June 2019; accepted 18 December 2019 Abstract Perspective plays an important role in the creation and appreciation of depth on paper and canvas. Paintings of extant scenes are interesting objects for studying perspective, because such paintings provide insight into how painters apply different aspects of perspective in creating highly admired paintings. In this regard the paintings of the Piazza San Marco in Venice by Canaletto in the eigh- teenth century are of particular interest because of the Piazza’s extraordinary geometry, and the fact that Canaletto produced a number of paintings from similar but not identical viewing positions throughout his career. Canaletto is generally regarded as a great master of linear perspective. Analysis of nine paintings shows that Canaletto almost perfectly constructed perspective lines and vanishing points in his paintings. Accurate reconstruction is virtually impossible from observation alone be- cause of the irregular quadrilateral shape of the Piazza. Use of constructive tools is discussed. The geometry of Piazza San Marco is misjudged in three paintings, questioning their authenticity. Sizes of buildings and human figures deviate from the rules of linear perspective in many of the analysed paintings. Shadows are stereotypical in all and even impossible in two of the analysed paintings. The precise perspective lines and vanishing points in combination with the variety of sizes for buildings and human figures may provide insight in the employed production method and the perceptual experi- ence of a given scene. -

In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Books, pamphlets, catalogues, and scrapbooks Collections, Digitized Books 1908 In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College M. Carey Thomas Bryn Mawr College Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Custom Citation Thomas, M. Carey, In Memory of Walter Cope, Architect of Bryn Mawr College. (Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania: Bryn Mawr College, 1908). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. https://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_books/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. #JI IN MEMORY OF WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Service held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. , • y • ./S-- I I .... ~ .. ,.,, \ \ " "./. "",,,, ~ / oj. \ .' ' \£,;i i f 1 l; 'i IN MEMORY OF \ WALTER COPE ARCHITECT OF BRYN MAWR COLLEGE Address delivered by President M. Carey Thomas at a Memorial Servic~ held at Bryn Mawr College, November 4, 1902. Published in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, February, 1905. Reprinted by request, June, 1908. • T his memorial address was published originally in the Bryn Mawr College Lantern, Februar)I, I905, and is now reprinted by perntission of the Board of Editors of the Lantern, with slight verbal changesJ in response to the request of some of the many adm1~rers of the architectural beauty of Bryn 1\;[awr College, w'ho believe that it should be more widely l?nown than it is that the so-called American Collegiate Gothic was created for Bryn Mawr College by the genius of John Ste~vardson and ""Valter Cope. -

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

CTBUH Journal

About the Council The Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat is the world’s leading resource for professionals CTBUH Journal focused on the inception, design, construction, and International Journal on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat operation of tall buildings and future cities. A not-for-profi t organization, founded in 1969 and based at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, CTBUH has an Asia offi ce at Tongji University, Shanghai, and a research offi ce at Iuav Tall buildings: design, construction, and operation | 2015 Issue II University, Venice, Italy. CTBUH facilitates the exchange of the latest knowledge available on tall buildings around the world through publications, Special Issue: Focus on Japan research, events, working groups, web resources, and its extensive network of international representatives. The Council’s research department Case Study: Abenos Harukas, Osaka is spearheading the investigation of the next generation of tall buildings by aiding original Advanced Structural Technologies research on sustainability and key development For High-Rise Buildings In Japan issues. The free database on tall buildings, The Skyscraper Center, is updated daily with detailed Next Tokyo 2045: A Mile-High Tower information, images, data, and news. The CTBUH Rooted In Intersecting Ecologies also developed the international standards for measuring tall building height and is recognized as Application of Seismic Isolation Systems the arbiter for bestowing such designations as “The World’s Tallest Building.” In Japanese High-Rise -

The “International” Skyscraper: Observations 2. Journal Paper

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The “International” Skyscraper: Observations Author: Georges Binder, Managing Director, Buildings & Data SA Subject: Urban Design Keywords: Density Mixed-Use Urban Design Verticality Publication Date: 2008 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2008 Issue I Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Georges Binder The “International” Skyscraper: Observations While using tall buildings data, the following paper aims to show trends and shifts relating to building use and new locations accommodating high-rise buildings. After decades of the American office building being dominate, in the last twelve years we have observed a gradual but major shift from office use to residential and mixed-use for Tall Buildings, and from North America to Asia. The turn of the millennium has also seen major changes in the use of buildings in cities having the longest experience with Tall Buildings. Chicago is witnessing a series of office buildings being transformed into residential or mixed-use buildings, a phenomenon also occurring on a large scale in New York. In midtown Manhattan of New York City we note the transformation of major hotels into residential projects. The transformation of landmark projects in midtown New York City is making an impact, but it is not at all comparable to the number of new projects being built in Asia. When conceiving new projects, we should perhaps bear in mind that, in due time, these will also experience major shifts in uses and we should plan for this in advance. -

JAKO201834663385082.Pdf

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of September 2018, Vol 7, No 3, 197-214 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2018.7.3.197 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Developments of Structural Systems Toward Mile-High Towers Kyoung Sun Moon† Yale University School of Architecture, 180 York Street, New Haven, CT 06511, USA Abstract Tall buildings which began from about 40 m tall office towers in the late 19th century have evolved into mixed-use megatall towers over 800 m. It is expected that even mile-high towers will soon no longer be a dream. Structural systems have always been one of the most fundamental technologies for the dramatic developments of tall buildings. This paper presents structural systems employed for the world’s tallest buildings of different periods since the emergence of supertall buildings in the early 1930s. Further, structural systems used for today’s extremely tall buildings over 500 m, such as core-outrigger, braced mega- tube, mixed, and buttressed core systems, are reviewed and their performances are studied. Finally, this paper investigates the potential of superframed conjoined towers as a viable structural and architectural solution for mile-high and even taller towers in the future. Keywords: Tall buildings, Tallest buildings, Core-outrigger systems, Braced megatubes, Mixed systems, Buttressed core systems, Superframed conjoined towers, Mile-high towers 1. Introduction and the height race was culminated with the 381 m tall 102-story Empire State Building of 1931 also in New York. Tall buildings emerged in the late 19th century in New Due to the Great Depression and Second World War, dev- York and Chicago. -

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force

Report of the Fine Arts Library Task Force University of Texas at Austin April 2, 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................... 4 Inputs to the Task Force ......................................................................................................... 6 Charge 1 ................................................................................................................................ 9 Offsite Storage, Cooperative Collection Management, and Print Preservation .................................9 Closure and Consolidation of Branch Libraries ............................................................................... 10 Redesign of Library Facilities Housing Academic and Research Collections ..................................... 10 Proliferation of Digital Resources and Hybrid Collections .............................................................. 11 Discovery Mechanisms ................................................................................................................. 12 Charge 2 .............................................................................................................................. 14 Size of the Fine Arts Library Collection .......................................................................................... 14 Use of the Fine Arts -

5 Aboutthepennmuseum

NEWS RELEASE Pam Kosty, Public Relations Director 215.898.4045 [email protected] ABOUT THE PENN MUSEUM Founded in 1887, the Penn Museum (University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) is an internationally renowned museum and research institution dedicated to the understanding of cultural diversity and the exploration of the history of humankind. In its 130-year history, the Penn Museum has sent more than 350 research expeditions around the world and collected nearly one million obJects, many obtained directly through its own excavations or anthropological and ethnographic research. Art and Artifacts from across Continents and throughout Time Three gallery floors feature art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, North and Central America, Asia, Africa, and the ancient Mediterranean World. Special exhibitions drawn both from the Museum’s own collections and brought in on loan enrich the gallery offerings. Ancient Egyptian treasures on display include monumental architectural elements from the Palace of Merenptah, mummies, and a 15-ton granite Sphinx—the largest Sphinx in the Western Hemisphere. Canaan and Ancient Israel features Near East artifacts and looks at the crossroads of cultures in that dynamic region. Worlds Intertwined, a suite of ancient Mediterranean World galleries, features more than 1,400 artifacts from Greece, Etruscan Italy, and the Roman world. The Museum’s Africa Gallery features material from throughout that vast continent, including fine West and Central African masks and instruments and an acclaimed Benin bronze collection from Nigeria, while an adJacent Imagine Africa with the Penn Museum proJect invites visitors to share perspectives and make suggestions for future African exhibitions. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

OLMSTED TRACT; Torrance, California 2011 – 2013 SURVEY of HISTORIC RESOURCES

OLMSTED TRACT; Torrance, California 2011 – 2013 SURVEY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES II. HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT A. Torrance and Garden City Movement: The plan for the original City of Torrance, known as the Olmsted Tract, owes its origins to a movement that begin in England in the late 19th Century. Sir Ebenezer Howard published his manifesto “Garden Cities of To-morrow" in 1898 where he describes a utopian city in which man lives harmoniously together with the rest of nature. The London suburbs of Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City were the first built examples of garden city planning and became a model for urban planners in America. In 1899 Ebenezer founded the Garden City Association to promote his idea for the Garden City ‘in which all the advantages of the most energetic town life would be secured in perfect combination with all the beauty and delight of the country.” His notions about the integration of nature with town planning had profound influence on the design of cities and the modern suburb in the 20th Century. Examples of Garden City Plans in America include: Forest Hills Gardens, New York (by Fredrick Law Olmsted Jr.); Radburn, New Jersey; Shaker Heights, Ohio; Baldwin Hills Village, in Los Angeles, California and Greenbelt, Maryland. Fredrick Law Olmsted is considered to be the father of the landscape architecture profession in America. He had two sons that inherited his legacy and firm. They practiced as the Olmsted Brothers of Brookline Massachusetts. Fredrick Law Olmsted Junior was a founding member of The National Planning Institute of America and was its President from 1910 to 1919. -

H. H. Richardson's House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered

H. H. Richardson’s House for Reverend Browne, Rediscovered mark wright Wright & Robinson Architects Glen Ridge, New Jersey n 1882 Henry Hobson Richardson completed a mod- flowering, brief maturity, and dissemination as a new Amer- est shingled cottage in the town of Marion, overlook- ican vernacular. To abbreviate Scully’s formulation, the Iing Sippican Harbor on the southern coast of Shingle Style was a fusion of imported strains of the Eng- Massachusetts (Figure 1). Even though he had only seen it lish Queen Anne and Old English movements with a con- in a sadly diminished, altered state and shrouded in vines, in current revival of interest in the seventeenth-century 1936 historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock would neverthe- colonial building tradition in wood shingles, a tradition that less proclaim, on the walls of the Museum of Modern Art survived at that time in humble construction up and down (MoMA) in New York, that the structure was “perhaps the the New England seaboard. The Queen Anne and Old most successful house ever inspired by the Colonial vernac- English were both characterized by picturesque massing, ular.”1 The alterations made shortly after the death of its the elision of the distinction between roof and wall through first owner in 1901 obscured the exceptional qualities that the use of terra-cotta “Kent tile” shingles on both, the lib- marked the house as one of Richardson’s most thoughtful eral use of glass, and dynamic planning that engaged func- works; they also caused it to be misunderstood—in some tionally complex houses with their landscapes. -

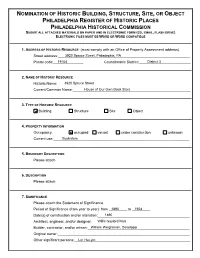

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3920 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3920 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:________House___________________________________________________ of Our Own Book Store 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Bookstore ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1924 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________