Pest Categorisation of Saperda Tridentata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Envenomations in Humans Caused by The

linica f C l To o x l ic a o n r l o u g o y J Amaral et al., J Clin Toxicol 2018, 8:4 Journal of Clinical Toxicology DOI: 10.4172/2161-0495.1000392 ISSN: 2161-0495 Case Report Open Access Envenomations in Humans Caused by the Venomous Beetle Onychocerus albitarsis: Observation of Two Cases in São Paulo State, Brazil Amaral ALS1*, Castilho AL1, Borges de Sá AL2 and Haddad V Jr3 1Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil 2Private Clinic, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil 3Departamento de Dermatologia e Radioterapia, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CP 557, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil *Corresponding author: Antonio L. Sforcin Amaral, Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista – UNESP, CEP 18618-000, Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil, Email: [email protected] Received date: July 23, 2018; Accepted date: August 21, 2018; Published date: August 24, 2018 Copyright: ©2018 Amaral ALS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Beetles (Coleoptera) are the most diverse group of animals in the world and occur in many environments. In Atlantic and Amazon rainforests, the scorpion-beetle Onychocerus albitarsis (Cerambycidae), can be found. It has venom glandules and inoculators organs in the antenna extremities. Two injuries in humans are reported, showing different patterns of skin reaction after the stings. -

Vii Congreso De Estudiantes Universitarios De Ciencia, Tecnología E Ingeniería Agronómica

VII CONGRESO DE ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS DE CIENCIA, TECNOLOGÍA E INGENIERÍA AGRONÓMICA Escuela Técnica Superior de Ingenieros Agrónomos Universidad Politécnica de Madrid Madrid, 5 y 6 de mayo de 2015 COMITÉ ORGANIZADOR Profesora Pilar García Rebollar Estudiantes Iñigo Mauleón Pérez María Rodríguez Francisco Vocales Silverio Alarcón Lorenzo Carlos Hernández Díaz-Ambrona María Remedios Alvir Morencos Ignacio Mariscal Sancho Augusto Arce Martínez Mª Ángeles Mendiola Ubillos Mª Antonia Bañuelos Bernabé David Menoyo Luque Raúl Sánchez Calvo Rodríguez Felipe Palomero Rodríguez Mercedes Flórez García Margarita Ruiz Ramos José María Fuentes Pardo José Francisco Vázquez Muñiz Ana Isabel García García Morris Villarroel Robinson VII Congreso de Estudiantes Universitarios de Ciencia, Tecnología e Ingeniería Agronómica PRÓLOGO En este VII Congreso de estudiantes volvemos agradecer a todos los profesores y alumnos su participación y colaboración en todo momento para que en este Libro de Actas que tienes entre tus manos se hayan recopilado los trabajos de más de 100 estudiantes. Todos los trabajos han sido revisados por los profesores del Comité Científico del Congreso y esperamos que las correcciones hayan sido de utilidad a los autores. Ya sólo queda “la puesta en escena” con la exposición y los nervios de hablar en público. Se dice que “no hay temas aburridos, sino oradores poco entusiastas”. Sabemos que nuestros estudiantes, si se han lanzado a presentar su trabajo en este Congreso, es porque entusiasmo no les falta, y los organizadores del Congreso vamos a hacer todo lo posible para que no decaiga. No obstante, como en cualquier otro evento de este tipo, tenemos un tiempo limitado y esperamos que los ponentes controlen su entusiasmo y sepan respetarlo. -

11-16589 PRA Record Saperda Candida

PRA Saperda candida 11-16589 (10-15760, 09-15659) European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation Organisation Européenne et Méditerranéenne pour la Protection des Plantes Guidelines on Pest Risk Analysis Decision-support scheme for quarantine pests Version N°3 Pest Risk Analysis for Saperda candida Pest risk analysts: Expert Working group for PRA for Saperda candida (met in 2009-11) ANDERSON Helen (Ms) - The Food and Environment Research Agency (GB) AGNELLO Arthur (Mr) - Department of Entomology New York State Agricultural Experiment Station(USA) BAUFELD Peter (Mr) - Julius Kühn Institut (JKI), Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Institute for National and International Plant Health (DE) GILL Bruce D. (Mr) - Head Entomology, Ottawa Plant Laboratories, C.F.I.A. (CA) PFEILSTETTER Ernst (Mr) - Julius Kühn Institut (JKI), Federal Research Centre for Cultivated Plants, Institute for National and International Plant Health (DE) (core member) STEFFEK Robert (Mr) - Austrian Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES), Institute for Plant Health (AT) (core member) VAN DER GAAG Dirk Jan (Mr) - Plant Protection Service (NL) (core member) The Section on risk management was reviewed by the EPPO Panel on Phytosanitary Measures in 2010-02-18. 1 PRA Saperda candida Stage 1: Initiation 1 Identification of a In summer 2008, the presence of Saperda candida was detected for the first time in Germany and in Europe (Nolte & Give the reason for performing the PRA single pest Krieger, 2008). This wood boring insect was observed on the island of Fehmarn on urban trees ( Sorbus intermedia and other host plants) and eradication measures were taken against it. S. candida is considered as a pest of apple trees and other tree species in North America. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

(Coleoptera) of Peru Miguel A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2-29-2012 Preliminary checklist of the Cerambycidae, Disteniidae, and Vesperidae (Coleoptera) of Peru Miguel A. Monné Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, [email protected] Eugenio H. Nearns University of New Mexico, [email protected] Sarah C. Carbonel Carril Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Peru, [email protected] Ian P. Swift California State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Marcela L. Monné Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Monné, Miguel A.; Nearns, Eugenio H.; Carbonel Carril, Sarah C.; Swift, Ian P.; and Monné, Marcela L., "Preliminary checklist of the Cerambycidae, Disteniidae, and Vesperidae (Coleoptera) of Peru" (2012). Insecta Mundi. Paper 717. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/717 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0213 Preliminary checklist of the Cerambycidae, Disteniidae, and Vesperidae (Coleoptera) of Peru Miguel A. Monné Museu Nacional Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Quinta da Boa Vista São Cristóvão, 20940-040 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil Eugenio H. Nearns Department of Biology Museum of Southwestern Biology University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001, USA Sarah C. Carbonel Carril Departamento de Entomología Museo de Historia Natural Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Avenida Arenales 1256, Lima, Peru Ian P. -

The Evolution and Genomic Basis of Beetle Diversity

The evolution and genomic basis of beetle diversity Duane D. McKennaa,b,1,2, Seunggwan Shina,b,2, Dirk Ahrensc, Michael Balked, Cristian Beza-Bezaa,b, Dave J. Clarkea,b, Alexander Donathe, Hermes E. Escalonae,f,g, Frank Friedrichh, Harald Letschi, Shanlin Liuj, David Maddisonk, Christoph Mayere, Bernhard Misofe, Peyton J. Murina, Oliver Niehuisg, Ralph S. Petersc, Lars Podsiadlowskie, l m l,n o f l Hans Pohl , Erin D. Scully , Evgeny V. Yan , Xin Zhou , Adam Slipinski , and Rolf G. Beutel aDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; bCenter for Biodiversity Research, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN 38152; cCenter for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Arthropoda Department, Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; dBavarian State Collection of Zoology, Bavarian Natural History Collections, 81247 Munich, Germany; eCenter for Molecular Biodiversity Research, Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, 53113 Bonn, Germany; fAustralian National Insect Collection, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; gDepartment of Evolutionary Biology and Ecology, Institute for Biology I (Zoology), University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany; hInstitute of Zoology, University of Hamburg, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany; iDepartment of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Wien, Wien 1030, Austria; jChina National GeneBank, BGI-Shenzhen, 518083 Guangdong, People’s Republic of China; kDepartment of Integrative Biology, Oregon State -

Genomics of Systemic Induced Defense Responses to Insect Herbivory in Hybrid Poplar

GENOMICS OF SYSTEMIC INDUCED DEFENSE RESPONSES TO INSECT HERBIVORY IN HYBRID POPLAR by RYAN NICHOLAS PHILIPPE B.Sc. (Hon.), the University of British Columbia, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED 1N PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Botany) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 2008 © Ryan Nicholas Philippe, 2008 Abstract The availability of a poplar (Populus trichocarpa Torr & A. Gray, bLack cottonwood) genome sequence is enabling new research approaches in angiosperm tree biology. Much of the recent genomics research in popLars has been on wood formation, growth and deveLopment, and abiotic stress tolerance, motivated, at Least in part, by the fact that popLars provide an important system for Large scale, short-rotation pLantation forestry in the Northern Hemisphere. Given their widespread distribution and long lifespan, poplar trees are threatened by a Large variety of insect herbivore pests, and must deal with their attacks with a successfuL defense response. To sustain productivity and ecosystem health of natural and planted poplar forests, it is of critical importance to develop a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of defense and resistance of poplars against insect pests. Previous research has established a soLid foundation of the chemical ecology of poplar defense against base with Large-scaLe profiling of transcriptome responses of insects. In this study, I buiLd on this popLar trees to insect herbivory. A 15,496-clone cDNA microarray was developed and used to anaLyse transcriptome responses through time to a variety of insect, mechanicaL, and chemicaL eLicitor treatments in treated source leaves, as well as in undamaged systemic source and sink leaves of hybrid poplar (Populus trichocarpa x deltoides). -

And Lepidoptera Associated with Fraxinus Pennsylvanica Marshall (Oleaceae) in the Red River Valley of Eastern North Dakota

A FAUNAL SURVEY OF COLEOPTERA, HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH FRAXINUS PENNSYLVANICA MARSHALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By James Samuel Walker In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Department: Entomology March 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School North DakotaTitle State University North DaGkroadtaua Stet Sacteho Uolniversity A FAUNAL SURVEYG rOFad COLEOPTERA,uate School HEMIPTERA (HETEROPTERA), AND LEPIDOPTERA ASSOCIATED WITH Title A FFRAXINUSAUNAL S UPENNSYLVANICARVEY OF COLEO MARSHALLPTERTAitl,e HEM (OLEACEAE)IPTERA (HET INER THEOPTE REDRA), AND LAE FPAIDUONPATLE RSUAR AVSESYO COIFA CTOEDLE WOIPTTHE RFRAA, XHIENMUISP PTENRNAS (YHLEVTAENRICOAP TMEARRAS),H AANLDL RIVER VALLEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA L(EOPLIDEAOCPTEEAREA) I ANS TSHOEC RIAETDE RDI VWEITRH V FARLALXEIYN UOSF P EEANSNTSEYRLNV ANNOICRAT HM DAARKSHOATALL (OLEACEAE) IN THE RED RIVER VAL LEY OF EASTERN NORTH DAKOTA ByB y By JAMESJAME SSAMUEL SAMUE LWALKER WALKER JAMES SAMUEL WALKER TheThe Su pSupervisoryervisory C oCommitteemmittee c ecertifiesrtifies t hthatat t hthisis ddisquisition isquisition complies complie swith wit hNorth Nor tDakotah Dako ta State State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of University’s regulations and meetMASTERs the acce pOFted SCIENCE standards for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE MASTER OF SCIENCE SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: David A. Rider DCoa-CCo-Chairvhiadi rA. -

EPPO Reporting Service

ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE EUROPEAN AND ET MEDITERRANEENNE MEDITERRANEAN POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES PLANT PROTECTION ORGANIZATION EPPO Reporting Service NO. 4 PARIS, 2018-04 General 2018/068 New data on quarantine pests and pests of the EPPO Alert List 2018/069 Quarantine lists of Kazakhstan (2017) 2018/070 EPPO report on notifications of non-compliance 2018/071 EPPO communication kits: templates for pest-specific posters and leaflets 2018/072 Useful publications on Spodoptera frugiperda Pests 2018/073 First report of Tuta absoluta in Tajikistan 2018/074 First report of Tuta absoluta in Lesotho 2018/075 First reports of Grapholita packardi and G. prunivora in Mexico 2018/076 First report of Scaphoideus titanus in Ukraine 2018/077 First report of Epitrix hirtipennis in France 2018/078 First report of Lema bilineata in Italy 2018/079 Eradication of Anoplophora glabripennis in Brünisried, Switzerland 2018/080 Update on the situation of Anoplophora glabripennis in Austria Diseases 2018/081 First report of Ceratocystis platani in Turkey 2018/082 Huanglongbing and citrus canker are absent from Egypt 2018/083 Xylella fastidiosa eradicated from Switzerland 2018/084 Update on the situation of Ralstonia solanacearum on roses in Switzerland 2018/085 First report of ‘Candidatus Phytoplasma fragariae’ in Slovenia Invasive plants 2018/086 Ambrosia artemisiifolia control in agricultural areas in North-west Italy 2018/087 Optimising physiochemical control of invasive Japanese knotweed 2018/088 Update on LIFE project IAP-RISK 2018/089 Conference: Management and sharing of invasive alien species data to support knowledge-based decision making at regional level (2018-09-26/28, Bucharest, Romania) 21 Bld Richard Lenoir Tel: 33 1 45 20 77 94 E-mail: [email protected] 75011 Paris Fax: 33 1 70 76 65 47 Web: www.eppo.int EPPO Reporting Service 2018 no. -

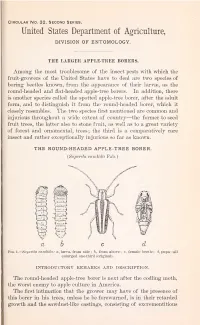

The Larger Apple-Tree Borers

Circular No. 32, Second Series. United States Department of Agriculture, DIVISION OF ENTOMOLOGY. THE LARGER APPLE-TREE BORERS. Among the most troublesome of the insect pests with which the fruit-growers of the United States have to deal are two species of boring beetles known, from the appearance of their larvse, as the round-headed and flat-headed apple-tree borers. In addition, there is another species called the spotted apple-tree borer, after the adult form, and to distinguish it from the round-headed borer, which it closely resembles. The two species first mentioned are common and injurious throughout a wide extent of country—the former to seed fruit trees, the latter also to stone fruit, as well as to a great variety of forest and ornamental, trees; the third is a comparatively rare insect and rather exceptionally injurious so far as known. THE ROUND-HEADED APPLE-TREE BORER. (Saperda Candida Fab.) Fig. 1.—Saperda Candida: a, larva, from side; b, from above; c, female beetle; d, pupa—all enlarged one-third (original). INTRODUCTORY REMARKS AND DESCRIPTION. The round-headed apple-tree borer is next after the codling moth, the worst enemy to apple culture in America. The first intimation that the grower may have of the presence of this borer in his trees, unless he be forewarned, is in their retarded growth and the sawdust-like castings, consisting of excrementitious matter and gnawings of woody fiber, which the larvae extrude from openings into their burrows. This manifestation is usually accom- panied by more or less evident discoloration of the bark, and, in early spring, particularly, slight exudation of sap. -

Your Name Here

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DEAD WOOD AND ARTHROPODS IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES by MICHAEL DARRAGH ULYSHEN (Under the Direction of James L. Hanula) ABSTRACT The importance of dead wood to maintaining forest diversity is now widely recognized. However, the habitat associations and sensitivities of many species associated with dead wood remain unknown, making it difficult to develop conservation plans for managed forests. The purpose of this research, conducted on the upper coastal plain of South Carolina, was to better understand the relationships between dead wood and arthropods in the southeastern United States. In a comparison of forest types, more beetle species emerged from logs collected in upland pine-dominated stands than in bottomland hardwood forests. This difference was most pronounced for Quercus nigra L., a species of tree uncommon in upland forests. In a comparison of wood postures, more beetle species emerged from logs than from snags, but a number of species appear to be dependent on snags including several canopy specialists. In a study of saproxylic beetle succession, species richness peaked within the first year of death and declined steadily thereafter. However, a number of species appear to be dependent on highly decayed logs, underscoring the importance of protecting wood at all stages of decay. In a study comparing litter-dwelling arthropod abundance at different distances from dead wood, arthropods were more abundant near dead wood than away from it. In another study, ground- dwelling arthropods and saproxylic beetles were little affected by large-scale manipulations of dead wood in upland pine-dominated forests, possibly due to the suitability of the forests surrounding the plots. -

(Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 19 Number 3 - Fall 1986 Number 3 - Fall 1986 Article 3 October 1986 Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan D. C. L. Gosling Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Gosling, D. C. L. 1986. "Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains in Northern Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 19 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol19/iss3/3 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Gosling: Ecology of the Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) of the Huron Mountains i 1986 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 153 ECOLOGY OF THE CERAMBYCIDAE (COLEOPTERA) OF THE HURON MOUNTAINS IN NORTHERN MICHIGAN D. C. L Gosling! ABSTRACT Eighty-nine species of Cerambycidae were collected during a five-year survey of the woodboring beetle fauna of the Huron Mountains in Marquette County, Michigan. Host plants were deteTITIined for 51 species. Observations were made of species abundance and phenology, and the blossoms visited by anthophilous cerambycids. The Huron Mountains area comprises approximately 13,000 ha of forested land in northern Marquette County in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. More than 7000 ha are privately owned by the Huron Mountain Club, including a designated, 2200 ha, Nature Research Area. The variety of habitats combines with differences in the nature and extent of prior disturbance to produce an exceptional diversity of forest communities, making the area particularly valuable for studies of forest insects.