Dun Deardail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lochs & Castles with a Local | Privately Guided Tours Scotland | 4

scotland.nordicvisitor.com SCOTTISH LOCHS & CASTLES WITH A LOCAL ITINERARY DAY 1 DAY 1: ARRIVAL IN EDINBURGH Upon your arrival in Edinburgh, you will be greeted by a private driver who will take you to your hotel in the city centre. For those arriving early in the day, we recommend spending the afternoon walking through the city, strolling along the Royal Mile and exploring the Old Town and New Town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are also plenty of museums and landmarks to visit within the city centre, including the majestic Edinburgh Castle. Included: Entrance to Edinburgh Castle Spend the night in Edinburgh Attractions: Calton Hill, Edinburgh, Edinburgh Castle, Edinburgh New Town, Edinburgh Old Town, The Grassmarket, The Royal Mile & St Giles Cathedral DAY 2 DAY 2: WELCOME TO THE HIGHLANDS Today your guide will pick you up from your hotel in a comfortable vehicle to start your private tour. On the way you’ll have the option to go for a walk at the picturesque Hermitage and the Highland Folk Museum inside the Cairngorms National Park. Arriving near Inverness, you can visit the Battlefield of Culloden Moor, to see where the last battle on British soil occurred in 1746. Nearby you could also roam around Clava Cairns, a series of tombs and standing stones dating back roughly 4,000 years. Spend the night in Inverness area. Driving distance: 151 miles / 243 km Average travel & exploring duration: estimated 8-9 hours Attractions: Cairngorms National Park, Clava Cairns, Culloden Battlefield & Visitor Centre, Highland Folk Museum, Inverness, The Hermitage DAY 3 DAY 3: LOCH NESS, CASTLES & BRAVEHEART COUNTRY Today’s drive will take you back to Edinburgh (you also have the option to end your tour in Glasgow in the optional activities below), via Fort William and Braveheart Country. -

Eat – Stay – See – Fort William.Pdf

Eat | Stay | See | Fort William If you are visiting Fort William, here are some options for accommodation, with a range to suit every budget. All accommodations are located within central Fort William, or are just a short journey from the train station. Accommodation List | Fort William Inverlochy Castle Myrtle Bank Guest House 5 Star Country House Hotel. Inverlochy is one 4 Star Guest House in a 1890’s Victorian villa located of Scotland’s finest luxury hotels beside Loch Linhe on the South side of Fort William Address: Torlundy, Fort William PH33 6SN Address: Achintore Rd, Fort William PH33 6RQ Location: 3.6 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Location: 1.1 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Phone: +44 (0)1397 702177 Phone: +44 (0)1397 702034 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.inverlochycastle.com Web: www.myrtlebankguesthouse.co.uk The Grange Huntingtower Lodge 5 Star Bed and Breakfast set high above Loch Linnhe with 4 Star Bed and Breakfast (Gold Green Tourism Award) superb views to the Ardgour hills Address: Druimarbin, Fort William, PH33 6RP Address: The Grange, Grange Road, Fort William, PH33 6JF Location: 2.7 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Location: 1.3 miles to Tom-na-Faire Station Square Phone: +44 (0)1397 700 079 Phone: +44 (0)1397 705 516 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.huntingtowerlodge.com Web: www.grangefortwilliam.com When making a reservation, please mention that Wilderness Scotland have recommended them as a place to stay within Fort William. -

The Royal Citadel of Messina. Hypothesis of Architectural

Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean. XV to XVIII centuries / Vol II / Rodríguez-Navarro (Ed.) © 2015 Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/FORTMED2015.2015. 1716 The Royal Citadel of Messina. Hypothesis of architectural restoration for the conservation and use Fabrizio Armaleoa, Marco Bonnab, Maria Grazia Isabel Brunoc, Sebastiano Buccad, Valentina Cutropiae, Nicola Faziof, Luigi Feliceg, Federica Gullettah, Vittorio Mondii, Elena Morabitol, Carmelo Rizzom aESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected],bESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], cESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], dESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], eESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], fESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], g ESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], hESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], iESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], lESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected], mESEMeP, Messina, Italy, [email protected] Abstract The hypothesis of architectural restoration wants to ensure the conservation and the use of the Royal Citadel through a conscious reinterpretation of the work and a cautious operation of image reintegration. The Royal Citadel of Messina, wanted by the King of Spain Charles II of Habsburg, was designed and built, at the end of the XVII century, by the military engineer Carlos de Grunenbergh. It is a "start fort" located at the entrance of its natural Sickle port, that is a strategic place for controlling the Strait of Messina, the port and especially the people living here. The project is neither retrospective or imitative of the past forms, nor free from the constraints and guidelines resulting from the historical-critical understanding, but conducted with conceptual rigor and with the specific aim of transmitting the monument to the future in the best possible conditions, even with the assignment of a new function. -

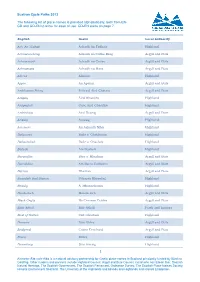

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Hand-Made Pottery in the Prehistoric and Roman Period in Northern England and Southern Scotland

Durham E-Theses Native Pottery: hand-made pottery in the prehistoric and Roman period in northern England and southern Scotland Plowright, Georgina How to cite: Plowright, Georgina (1978) Native Pottery: hand-made pottery in the prehistoric and Roman period in northern England and southern Scotland, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9824/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 NATIVE POTTERY: HAND-MADE POTTERY IN THE PREHISTORIC AND ROMAN PERIOD IN NORTHERN ENGLAND AND SOUTHERN SCOTLAND 'Thesis presented for the Degree of M.A. University of Durham Georgina Plowright October 1978 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Abstract The thesis is a survey and catalogue of most of the pottery found in the area between the Clyde and Solway and the southern boundaries of Cumbria and Durham, and to which previously the label of Iron Age or Roman native pottery had been assigned. -

The Halifax Citadel

THE HALIFAX CITADEL National Historic Park Halifax, Nova Scotia Issued under the authority of the Honourable Arthur Laing, P.C., M.P., B.S.A., Minister of Northern Affairs and National Resources HALIFAX CITADEL NOVA SCOTIA THE HALIFAX CITADEL Halifax, Nova Scotia Halifax was founded in 1749 to provide a base for the British Navy and Army and a springboard for attack on the French at Louisbourg and Quebec, because the final contest between France and England for possession of the North American continent was clearly approaching. Citadel Hill was always the innermost keep and chief land defence of the Halifax Fortress. Four forts were built, at different periods, on its summit. The first was part of a wooden palisade around the young settlement, designed to protect the settlers from Indians. The second was built at the time of the American Revolution and was intended as a stronghold and base against the rebels. The third was built while Napoleon Bonaparte was trying to conquer the world, and this one was later repaired for the War of 1812 with the United States. Because of the latter war, Britain knew she must have a permanent fortress here as Atlantic base in time of peril, and so the fourth, the present one, was constructed. Not one of these forts was ever called upon to resist invasion. No shot was ever fired against them in anger. However, it is safe to say that they had served their purpose merely by existing. The First Citadel When the Honourable Edward Cornwallis arrived at Chebucto Harbour on June 21, 1749, accompanied by more than 2,500 settlers, one of his first thoughts was to secure the settlement from attacks by marauding Indians, ever ready to molest the British during periods of nominal peace between England and France. -

New Light on Oblong Forts: Excavations at Dunnideer, Aberdeenshire

Proc Soc Antiq Scot NEW140 (2010), LIGHT 79–91 ON OBLONG FORTS: EXCAVATIONS AT DUNNIDEER, ABERDEENSHIRE | 79 New light on oblong forts: excavations at Dunnideer, Aberdeenshire Murray Cook* with contributions by Hana Kdolska, Lindsay Dunbar, Rob Engl, Stefan Sagrott, Denise Druce and Gordon Cook ABSTRACT This paper presents the results of the excavation of a single keyhole trench at the oblong vitrified fort of Dunnideer, Aberdeenshire, along with a brief history of the study of oblong forts and vitrification. The excavation yielded two radiocarbon dates derived from destruction layers, which are discussed along with the results of a limited programme of archaeomagnetic dating at the same location. INTRODUCTION ramparts, it also has an entrance so may not be part of the oblong fort series. In addition, The series of oblong, gateless and often there has been significant debate over vitrified forts are one of the iconic type-sites of contradictory sets of dating evidence from the the Scottish Iron Age. Their study echoes the series (Alexander 2002). This article presents development of modern Scottish archaeology, the results and implications of the first new with its origins in the intellectual explosion excavation evidence for over 30 years. of the Scottish enlightenment; indeed, the earliest research (Williams 1777) just predates the founding of the Society of Antiquaries ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND of Scotland in 1781. However, despite over 200 years of study, their function and date The forts in question are rectangular, with remain uncertain. This is largely because only massive stone timber-laced ramparts, two examples have been subject to modern frequently vitrified, without obvious excavation: Finavon, Tayside (MacKie 1969a entrances, often on prominent hilltops, and and 1976) and Craig Phadrig, Inverness ranging widely in area by a factor of 10 from (Small & Cottam 1972). -

Citadel of Masyaf

GUIDEBOOK English version TheThe CCitadelitadel ofof MMasyafasyaf Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Description, History, Site Plan & Visitor Tour Frontispiece: The Arabic inscription above the basalt lintel of the monumental doorway into the palace in the Inner Castle. This The inscription is dated to 1226 AD, and lists the names of “Alaa ad-Dunia of wa ad-Din Muhammad, Citadel son of Hasan, son of Muhammad, son of Hasan (may Allah grant him eternal power); under the rule of Lord Kamal ad- Dunia wa ad-Din al-Hasan, son of Masa’ud (may Allah extend his power)”. Masyaf Opposite: Detail of this inscription. Text by Haytham Hasan The Aga Khan Trust for Culture is publishing this guidebook in cooperation with the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums as part of a programme for the Contents revitalisation of the Citadel of Masyaf. Introduction 5 The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, Geneva, Switzerland (www.akdn.org) History 7 © 2008 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. Printed in Syria. Site Plan 24 Visitor Tour 26 ISBN: 978-2-940212-06-4 Introduction The Citadel of Masyaf Located in central-western Syria, the town of Masyaf nestles on an eastern slope of the Syrian coastal mountains, 500 metres above sea level and 45 kilometres from the city of Hama. Seasonal streams flow to the north and south of the city and continue down to join the Sarout River, a tributary of the Orontes. -

3-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking

3-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Scottish Highlands & Scotland Trip code: LLBOB-3 2, 5 & 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Glen Coe is arguably one of the most celebrated glens in the world with its volcanic origins, and its dramatic landscapes offering breathtaking scenery – magnificent peaks, ridges and stunning seascapes.Easy walks are available, although if you’re up for the challenge we have walks designed to test your stamina and bravery where you can tackle some of Scotland's best mountains. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 2 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery and history of the Scottish Highlands • Opportunity to climb famous summits and bag 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) • Explore the dramatic glens and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. • Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life. TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Levels 2, 5 and Level 6. Discover the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands on our guided walks. We offer the opportunity to climb famous summits, with many 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) on our itinerary. Alternatively explore the dramatic valleys and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life. Our experienced guides offer the choice of up to three different walks each day Choose the option which best suits your interests and fitness We provide flexible holidays. -

7-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking

7-Night Scottish Highlands Guided Walking Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Scottish Highlands & Scotland Trip code: LLBOB-7 2, 5 & 6 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Glen Coe is arguably one of the most celebrated glens in the world with its volcanic origins, and its dramatic landscapes offering breathtaking scenery – magnificent peaks, ridges and stunning seascapes. Easy walks are available, although if you’re up for the challenge we have walks designed to test your stamina and bravery where you can tackle some of Scotland's best mountains. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery and history of the Scottish Highlands • Opportunity to climb famous summits and bag 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) • Explore the dramatic glens and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. • Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life. TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Levels 2, 5 and Level 6. Discover the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands on our guided walks. We offer the opportunity to climb famous summits, with many 'Munros' (mountains over 3,000ft) on our itinerary. Alternatively explore the dramatic valleys and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. -

Man in Moray

10 0 I w! Fig.2.1 Moray. MANIN MORAY 5,000 years of history Ian Keillar Synopsis The extent of Moray is defined and the physical conditions briefly described. Traces of Mesolithic man have been found in the Culbin, and later Neolithic peoples found Moray an attractive place to settle. As metal working became established, trades routes followed and Moray flourished. As the climate deteriorated, so, apparently, did the political situation and defensive sites became necessary. The Romans came and went and the Picts rose and fell. The Vikings did not linger on these shores and MacBeth never met any witches near Forres. The Kings of Scots divided and ruled until they themselves set a pattern, which still continues, that if you want to get on you must go south to London. In distant Moray, brave men like Montrose and foolish men like Prince Charles Edward, fought for their rightful king. The Stuarts, however, ill rewarded their followers. Road makers and bridge builders half tamed the rivers, and the railways com pleted the process. With wars came boom years for the farmers, but even feather beds wear out and Moray is once more in apparent decline. However, all declines are relative and the old adage still has relevance: 'Speak wee] o the Hielans but live in the Laich.' Physical The name Moray is now applied to a local authority administrative District extending from west of Forres and the Findhorn to Cullen and stretching down in an irregular triangle into the highlands of the Cairngorms (Fig.2. l ). In Medieval times, Moray reached as far as Lochalsh on the west coast and there has always been some difficulty in defining the bound aries of the province. -

Iron Age Scotland: Scarf Panel Report

Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Images ©as noted in the text ScARF Summary Iron Age Panel Document September 2012 Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Summary Iron Age Panel Report Fraser Hunter & Martin Carruthers (editors) With panel member contributions from Derek Alexander, Dave Cowley, Julia Cussans, Mairi Davies, Andrew Dunwell, Martin Goldberg, Strat Halliday, and Tessa Poller For contributions, images, feedback, critical comment and participation at workshops: Ian Armit, Julie Bond, David Breeze, Lindsey Büster, Ewan Campbell, Graeme Cavers, Anne Clarke, David Clarke, Murray Cook, Gemma Cruickshanks, John Cruse, Steve Dockrill, Jane Downes, Noel Fojut, Simon Gilmour, Dawn Gooney, Mark Hall, Dennis Harding, John Lawson, Stephanie Leith, Euan MacKie, Rod McCullagh, Dawn McLaren, Ann MacSween, Roger Mercer, Paul Murtagh, Brendan O’Connor, Rachel Pope, Rachel Reader, Tanja Romankiewicz, Daniel Sahlen, Niall Sharples, Gary Stratton, Richard Tipping, and Val Turner ii Iron Age Scotland: ScARF Panel Report Executive Summary Why research Iron Age Scotland? The Scottish Iron Age provides rich data of international quality to link into broader, European-wide research questions, such as that from wetlands and the well-preserved and deeply-stratified settlement sites of the Atlantic zone, from crannog sites and from burnt-down buildings. The nature of domestic architecture, the movement of people and resources, the spread of ideas and the impact of Rome are examples of topics that can be explored using Scottish evidence. The period is therefore important for understanding later prehistoric society, both in Scotland and across Europe. There is a long tradition of research on which to build, stretching back to antiquarian work, which represents a considerable archival resource.