POLICY REVIEW the Evolution of Indigenous Higher Education In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 to 8 Assembly

Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Northern Territory Government Ministries (CLP) 1st to 8 th Assembly 1974 - 2001 FIRST LETTS EXECUTIVE (November 1974 to August 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr P A E Everingham MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry SECOND LETTS EXECUTIVE (August 1975 to November 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr B F Kilgariff MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry THIRD LETTS EXECUTIVE (December 1975 to December 1976) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr G E J Tambling MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Community Development Mr M B Perron MLA Executive Member for Municipal -

Report on Statehood Program

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Report on Statehood Program Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Tabled February 2012 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Report on the Statehood Program Tabled in the Legislative Assembly in February 2012 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................... i Chair’s Overview ............................................................................................ ii Committee Members ..................................................................................... iv Committee Secretariat ................................................................................... v 1. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 2. Background.............................................................................................. 2 Recommendations of the SSC ................................................................................................. 2 Northern Territory Constitutional Convention Committee......................................................... 4 Information Campaign .............................................................................................................. 4 Current Status of the Statehood Program ................................................................................ 4 3. Convention Planning.............................................................................. -

Seventh Assembly

Index to Minutes of Proceedings – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 Thirteenth Assembly LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 INDEX TO MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS AND PAPERS TABLED Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 1 - 8 1 18 October 2016 9 – 14 2 19 October 2016 15 – 18 3 20 October 2016 19 – 23 4 25 October 2016 25 – 29 5 26 October 2016 31 – 35 6 27 October 2016 37 - 40 7 22 November 2016 41 - 45 8 23 November 2016 47 - 50 9 24 November 2016 51 - 56 10 29 November 2016 57 - 63 11 30 November 2016 65 - 68 12 1 December 2016 69 - 73 13 14 February 2017 75 - 80 14 15 February 2017 81 - 84 15 16 February 2017 85 - 89 16 14 March 2017 91 - 96 17 15 March 2017 97 - 100 18 16 March 2017 101 - 109 19 21 March 2017 111 - 113 20 22 March 2017 115 - 118 21 23 March 2017 119 - 123 22 2 May 2017 125 - 128 23 3 May 2017 129 - 131 24 4 May 2017 133 - 137 25 9 May 2017 139 - 144 26 10 May 2017 145 - 152 27 11 May 2017 153 - 159 28 22 June 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Pages 18 October 2016 22 June 2017 1 - 152 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. -

Northern Territory Statehood Steering Committee

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia The long road to statehood Report of the inquiry into the federal implications of statehood for the Northern Territory House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs May 2007 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2007 ISBN 978 0 642 78896 2 (Printed version) ISBN 978 0 642 78897 9 (HTML version) Cover design by the House of Representatives Publishing Office. Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................................vii Membership of the Committee ............................................................................................................ix Terms of reference..............................................................................................................................xi List of abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................xii Recommendation ..............................................................................................................................xiii THE REPORT 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 Background to the inquiry........................................................................................................ 1 The inquiry and report of the Committee............................................................................... -

Consolidated Index to Minutes of Proceedings

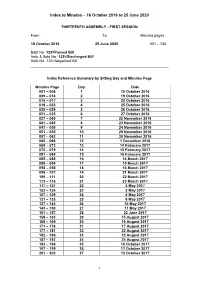

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 25 June 2020 001 – 746 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 – 008 1 18 October 2016 009 – 014 2 19 October 2016 015 – 017 3 20 October 2016 019 – 023 4 25 October 2016 025 – 029 5 26 October 2016 031 – 035 6 27 October 2016 037 – 040 7 22 November 2016 041 – 045 8 23 November 2016 047 – 050 9 24 November 2016 051 – 055 10 29 November 2016 057 – 063 11 30 November 2016 065 – 068 12 1 December 2016 069 – 073 13 14 February 2017 075 – 079 14 15 February 2017 081 – 084 15 16 February 2017 085 – 088 16 14 March 2017 089 – 094 17 15 March 2017 095 – 098 18 16 March 2017 099 – 107 19 21 March 2017 109 – 111 20 22 March 2017 113 – 116 21 23 March 2017 117 – 121 22 2 May 2017 123 – 126 23 3 May 2017 127 – 129 24 4 May 2017 131 – 135 25 9 May 2017 137 – 142 26 10 May 2017 143 – 150 27 11 May 2017 151 – 157 28 22 June 2017 159 – 163 29 15 August 2017 165 – 169 30 16 August 2017 171 – 176 31 17 August 2017 177 – 181 32 22 August 2017 183 – 186 33 23 August 2017 187 – 192 34 24 August 2017 193 – 196 35 10 October 2017 197 – 199 36 11 October 2017 201 – 203 37 12 October 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 205 – 208 38 17 October 2017 209 – 213 39 18 October 2017 215 – 220 40 19 October 2017 221 – 225 41 21 November 2017 227 – 233 42 22 November 2017 235 – 247 43 23 November -

The Politics of Euthanasia

The Politics of Euthanasia Robert G. Richardson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Politics School of History and Politics The University of Adelaide May 2008 Dedicated to my Mother & In memory of Rex Richardson (1996–2003) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................................................. VII DECLARATION ........................................................................................................................................VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..........................................................................................................................IX 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 2 WESTERN RESPONSES TO END OF LIFE CHOICE.................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 12 DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................................ 12 SUICIDE AND EUTHANASIA IN THE ANCIENT GREEK PERIOD ....................................................................... 13 SUICIDE AND EUTHANASIA IN ANCIENT ROME ........................................................................................... -

Contents Motion

DEBATES – Wednesday 15 February 2017 CONTENTS MOTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 833 Changes to Committee Membership – Public Accounts Committee and Select Committee on Opening Parliament to the People ......................................................................................................................... 833 TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY LAW REFORM BILL ............................................................................ 833 (Serial 15) ................................................................................................................................................ 833 MOTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 842 Note Statement – Supporting and Growing Jobs .................................................................................... 842 PETITION .................................................................................................................................................... 854 Petition No 7 – Bring Dan Murphy’s to Darwin ........................................................................................ 854 ELECTORAL LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL (NO 2) .......................................................................... 854 (Serial 8) ................................................................................................................................................. -

Informing the Euthanasia Debate: Perceptions of Australian Politicians

1368 UNSW Law Journal Volume 41(4) INFORMING THE EUTHANASIA DEBATE: PERCEPTIONS OF AUSTRALIAN POLITICIANS ANDREW MCGEE,* KELLY PURSER,** CHRISTOPHER STACKPOOLE,*** BEN WHITE,**** LINDY WILLMOTT***** AND JULIET DAVIS****** In the debate on euthanasia or assisted dying, many different arguments have been advanced either for or against legal reform in the academic literature, and much contemporary academic research seeks to engage with these arguments. However, very little research has been undertaken to track the arguments that are being advanced by politicians when Bills proposing reform are debated in Parliament. Politicians will ultimately decide whether legislative reform will proceed and, if so, in what form. It is therefore essential to know what arguments the politicians are advancing in support of or against legal reform so that these arguments can be assessed and scrutinised. This article seeks to fill this gap by collecting, synthesising and mapping the pro- and anti-euthanasia and assisted dying arguments advanced by Australian politicians, starting from the time the first ever euthanasia Bill was introduced. I INTRODUCTION Euthanasia attracts continued media, societal and political attention.1 In particular, voluntary active euthanasia (‘VAE’) and physician-assisted suicide * BA (Hons) (Lancaster), LLB (Hons) (QUT), LLM (QUT), PhD (Essex); Senior Lecturer, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. ** BA/LLB (Hons) (UNE), PhD (UNE); Senior Lecturer, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. *** LLB/BBus (Hons) (QUT), BCL (Oxford). **** LLB (Hons) (QUT), DPhil (Oxford), Professor, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. ***** BCom (UQ), LLB (Hons) (UQ), LLM (Cambridge), PhD (QUT); Professor, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. -

Euthanasia Politics in the Australian State and Territorial Parliaments

Euthanasia Politics in the Australian State and Territorial Parliaments A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Alison Plumb School of Politics and International Relations May 2014 ii I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the Australian National University is solely my own work. iii iv Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures……………………………………………………………...vii Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………...ix Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………xi Chapter 1:Introduction………………………….…………………………………….1 The Aims of the Thesis………………………………………………………………….1 Why Study Voluntary Euthanasia?...................................................................................2 End of Life Choices and the Law in Australia…………………………………………12 Definition of Key Terms………………………………………………………………..13 Key Findings and the Structure of the Thesis…………………………………………..16 Chapter 2: Investigating Euthanasia Politics……………………...………………...21 Research on ‘Morality Politics’…....…………………………………………………...21 The Debate Over Voluntary Euthanasia………………………………………………..23 The Political Processes Involved……………………………………………………….27 Research Questions……………………………………………………………………..39 The Original Contribution of the Thesis………………………………………………..41 Methodology………………...………………………………………………………….42 Research Methods………………………………………………………………………46 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...52 Chapter 3: Voluntary Euthanasia Law Reform in the Northern Territory………53 The Factors Contributing to Success: Nitschke and -

Paul Henderson Lia Finocchiaro

MOST POWERFUL 05 PAUL HENDERSON Hendo is the everywhere man. The former Chief Minister from 2007 to 2012 is now front and centre of the Territory’s economic fightback as co-chair of the Economic Reconstruction Commission with Andrew Liveris. With Liveris’ immense commitments nationally and overseas, Henderson will be the commission’s main go-to man on the ground in the NT. As Chief Minister, Henderson played a pivotal role in securing the $60 billion lchthys LNG project for Darwin, the second largest investment in Australia’s history and the largest investment outside of Japan by a Japanese company. He is now a strategic business consultant and corporate counsel across northern Australia, chancellor of Charles Darwin University and a board member of the Energy Club NT. Originally from the United Kingdom, Henderson has been a proud Territorian since 1983. He had a background in marine engineering and IT before holding public service leadership positions and being elected to service in the NT Legislative Assembly in 1999. There are a few former state and national leaders who should take a leaf out of Hendo’s book, showing you can still make a meaningful difference when you leave office if you don’t become a vindictive, bitter wanker. LIA FINOCCHIARO Finocchiaro revived the CLP at the election and turned it into a real Opposition. The pint-sized CLP leader has taken the power effectively thrust upon her after the retirement of Gary Higgins and run with it. With her at the helm, the CLP has managed to increase its numbers in parliament from two MLAs to eight. -

First Session

Index to Minutes – 26 November 2013 to 5 December 2013 TWELFTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 26 November 2013 5 December 2013 249 - 289 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 249 - 254 38 26 November 2013 255 - 263 39 27 November 2013 265 - 269 40 28 November 2013 271 - 275 41 3 December 2013 277 - 284 42 4 December 2013 285 - 289 43 5 December 2013 BILLS Advance Personal Planning (Consequential Amendments) Bill 2013 (Serial 54) .......... 258 Advance Personal Planning Bill 2013 (Serial 41) ........................................................... 258 Alcohol Protection Orders Bill 2013 (Serial 58) ....................................................... 265, 266 Care and Protection of Children Amendment (Charter of Rights) Bill 2013 (Serial 62) .. 278 Care and Protection of Children Amendment (Legal Representation and Other Matters) Bill 2013 (Serial 51) ............................................................................................. 278, 279 Children’s Commissioner Bill 2013 (Serial 52) ................................................................ 279 Community Housing Providers (National Uniform Legislation) Bill 2013 (Serial 48) ...... 274 Constitutional Convention (Election) Amendment Bill 2013 (Serial 47) .......................... 288 Energy Pipelines Amendment Bill 2013 (Serial 45) ........................................................ 273 Local Government Amendment -

Teaching Territory Style the Story of Northern Territory Public Education

TEACHING TERRITORY STYLE THE STORY OF NORTHERN TERRITORY PUBLIC EDUCATION AN HISTORICAL ACCOUNT JEANNIE AILENE BENNETT Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Education Faculty of Law, Business, Education and Arts Charles Darwin University March, 2017 ii Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... ix Declaration ................................................................................................................. xi Dedication ................................................................................................................ xiii Conventions ............................................................................................................. xiv Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... xvi Part 1 The Context ..................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 3 1.1 Researcher Standpoint ............................................................................................ 3 1.2 Significance of the Research ................................................................................ 11 1.3 The Political Impact on NT Education................................................................. 15 1.4 Aims of the Research ..........................................................................................