The Historical Context of Northern Territory Statehood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 to 8 Assembly

Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Northern Territory Government Ministries (CLP) 1st to 8 th Assembly 1974 - 2001 FIRST LETTS EXECUTIVE (November 1974 to August 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr P A E Everingham MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry SECOND LETTS EXECUTIVE (August 1975 to November 1975) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr B F Kilgariff MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Law Mr G E J Tambling MLA Executive Member for Community Development Ms E J Andrew MLA Executive Member for Education and Consumer Services Mr D L Pollock MLA Executive Member for Social Affairs Mr I L Tuxworth MLA Executive Member for Resource Development Mr R Ryan MLA Executive Member for Transport and Secondary Industry THIRD LETTS EXECUTIVE (December 1975 to December 1976) Dr G A Letts MLA Majority Leader and Executive Member for Primary Industry and the NT Public Service Mr G E J Tambling MLA Deputy Majority Leader and Executive Member for Finance and Community Development Mr M B Perron MLA Executive Member for Municipal -

Report on Statehood Program

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Report on Statehood Program Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Tabled February 2012 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Report on the Statehood Program Tabled in the Legislative Assembly in February 2012 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................... i Chair’s Overview ............................................................................................ ii Committee Members ..................................................................................... iv Committee Secretariat ................................................................................... v 1. Introduction.............................................................................................. 1 2. Background.............................................................................................. 2 Recommendations of the SSC ................................................................................................. 2 Northern Territory Constitutional Convention Committee......................................................... 4 Information Campaign .............................................................................................................. 4 Current Status of the Statehood Program ................................................................................ 4 3. Convention Planning.............................................................................. -

Vocational Education & Training

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION & TRAINING The Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy VOCATIONAL EDUCATION & TRAINING The Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy DON ZOELLNER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Zoellner, Don, author. Title: Vocational education and training : the Northern Territory’s history of public philanthropy / Don Zoellner. ISBN: 9781760460990 (paperback) 9781760461003 (ebook) Subjects: Vocational education--Government policy--Northern Territory. Vocational education--Northern Territory--History. Occupational training--Government policy--Northern Territory. Occupational training--Northern Territory--History. Aboriginal Australians--Vocational education--Northern Territory. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Northern Territory Parliament House main entrance’ by Patrick Nelson. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents List of figures . vii Foreword . xi Acknowledgements . xiii 1 . Setting the scene . 1 2 . Philanthropic behaviour . 11 3 . Prior to 1911: European discovery and South Australian administration of the Northern Territory . 35 4 . Early Commonwealth control, 1911–46 . 45 5 . The post–World War Two period to 1978 . 57 6. TAFE in the era of self‑government, 1978–92 . 99 7. Vocational education and training in the era of self‑government, 1992–2014 . 161 8. Late 2015 and September 2016 postscript . 229 References . 243 List of figures Figure 1. -

List of Figures

List of figures Figure 1. Paul Henderson, minister, second from right, and guests on the fifth-floor balcony of the Northern Territory Parliament House, 2005. 17 Figure 2. Paul AE Everingham, Member of the Legislative Assembly ..................................23 Figure 3. Charlotte Waters Telegraph Station, near the South Australian border, included a store and post office ...........37 Figure 4. Finke River Mission, September 1905 .................39 Figure 5. Tiwi people on Bathurst Island, January 1941, with Bishop Gsell. .40 Figure 6. Transfer Ceremony, 2 January 1911 ...................46 Figure 7. Catholic Mission School at Arltunga, January 1947 .......49 Figure 8. Train (Commonwealth line) with new engines, Northern South Australia, January 1920 ..................51 Figure 9. The first Legislative Council, 16 February 1948 ..........59 Figure 10. First Legislative Assembly sitting, 19 March 1975, in the cyclone-damaged chamber. Corrugated iron sheets in right foreground were used to channel rainwater away from members’ desks .................................60 Figure 11. Mission Aboriginals [sic] working in a carpentry shop, May 1968 .........................................65 Figure 12. Alice Springs High School from Anzac Hill, October 1958. This was the site of the Adult Education Centre and it became the first home of the Alice Springs Community College in 1974. 70 Figure 13. Electrical experiments at Darwin High School adult training classes, 30 June 1967 ......................71 vii VocatioNAL EducatioN ANd TRAiNiNg Figure 14. Darwin Primary School in January 1957, it later became Darwin Higher Primary and then Darwin High School. This building in Woods Street became the Adult Education Centre under principal Harold Garner ...........74 Figure 15. Apprentice training in the former World War Two railway workshops in Katherine, February 1974. -

Seventh Assembly

Index to Minutes of Proceedings – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 Thirteenth Assembly LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 INDEX TO MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS AND PAPERS TABLED Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 1 - 8 1 18 October 2016 9 – 14 2 19 October 2016 15 – 18 3 20 October 2016 19 – 23 4 25 October 2016 25 – 29 5 26 October 2016 31 – 35 6 27 October 2016 37 - 40 7 22 November 2016 41 - 45 8 23 November 2016 47 - 50 9 24 November 2016 51 - 56 10 29 November 2016 57 - 63 11 30 November 2016 65 - 68 12 1 December 2016 69 - 73 13 14 February 2017 75 - 80 14 15 February 2017 81 - 84 15 16 February 2017 85 - 89 16 14 March 2017 91 - 96 17 15 March 2017 97 - 100 18 16 March 2017 101 - 109 19 21 March 2017 111 - 113 20 22 March 2017 115 - 118 21 23 March 2017 119 - 123 22 2 May 2017 125 - 128 23 3 May 2017 129 - 131 24 4 May 2017 133 - 137 25 9 May 2017 139 - 144 26 10 May 2017 145 - 152 27 11 May 2017 153 - 159 28 22 June 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 22 June 2017 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Pages 18 October 2016 22 June 2017 1 - 152 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. -

Northern Territory Statehood Steering Committee

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia The long road to statehood Report of the inquiry into the federal implications of statehood for the Northern Territory House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs May 2007 Canberra © Commonwealth of Australia 2007 ISBN 978 0 642 78896 2 (Printed version) ISBN 978 0 642 78897 9 (HTML version) Cover design by the House of Representatives Publishing Office. Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................................vii Membership of the Committee ............................................................................................................ix Terms of reference..............................................................................................................................xi List of abbreviations ...........................................................................................................................xii Recommendation ..............................................................................................................................xiii THE REPORT 1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................1 Background to the inquiry........................................................................................................ 1 The inquiry and report of the Committee............................................................................... -

1990 Northern Territory Cabinet Records Booklet

1990 Northern Territory Cabinet Records Public release of the Cabinet Records FOURTH PERRON MINISTRY Back row: Hon. Steve Hatton MLA , Hon Max Ortmann MLA , Hon. Mike Reed MLA, Hon. Daryl Manzie MLA, Hon. Fred Finch MLA Front row: Hon. Roger Vale MLA, Hon. Marshall Perron MLA, Administrator Hon. Justice James Muirhead AC, Hon. Barry Coulter MLA, Hon. Shane Stone, MLA. Image courtesy of Library & Archives NT, Department of the Chief Minister, NTRS 3823 P1, Box 11, BW2950, Image 18 Strictly embargoed NOT for release until 1 January 2021 1990 NORTHERN TERRITORY CABINET RECORDS 2 Contact Details: Library & Archives NT Territory Families, Housing and Communities Kelsey Cresent Millner NT 0810 T: (08) 8924 7677 E: [email protected] W: www.nt.gov.au/archives 1990 NORTHERN TERRITORY CABINET RECORDS 3 Public release of the Cabinet records Under the Northern Territory Information Act, Cabinet submissions public sector organisations are required to transfer their records to Library & Archives NT Most business comes before Cabinet by not later than 30 years after the record was way of formal Cabinet submissions, each of created. which is allocated a consecutive number. Cabinet submissions generally follow a set Most archived records enter an “open access format. Submissions are usually prepared by period”, whereby they are available for public Government agencies at the direction of, or perusal 30 years after the record was created. with the agreement of, the Minister responsible This includes the Cabinet records. The original for that agency. Submissions may also include copies of all Northern Territory Cabinet comments from other Northern Territory submissions and decisions are filed by meeting Government agencies which were consulted date, and bound into books. -

Consolidated Index to Minutes of Proceedings

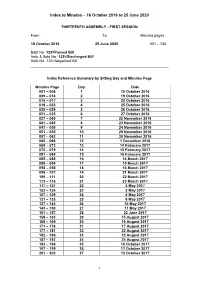

Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION From To Minutes pages 18 October 2016 25 June 2020 001 – 746 Bold No. 123=Passed Bill Italic & Bold No. 123=Discharged Bill Italic No. 123=Negatived Bill Index Reference Summary by Sitting Day and Minutes Page Minutes Page Day Date 001 – 008 1 18 October 2016 009 – 014 2 19 October 2016 015 – 017 3 20 October 2016 019 – 023 4 25 October 2016 025 – 029 5 26 October 2016 031 – 035 6 27 October 2016 037 – 040 7 22 November 2016 041 – 045 8 23 November 2016 047 – 050 9 24 November 2016 051 – 055 10 29 November 2016 057 – 063 11 30 November 2016 065 – 068 12 1 December 2016 069 – 073 13 14 February 2017 075 – 079 14 15 February 2017 081 – 084 15 16 February 2017 085 – 088 16 14 March 2017 089 – 094 17 15 March 2017 095 – 098 18 16 March 2017 099 – 107 19 21 March 2017 109 – 111 20 22 March 2017 113 – 116 21 23 March 2017 117 – 121 22 2 May 2017 123 – 126 23 3 May 2017 127 – 129 24 4 May 2017 131 – 135 25 9 May 2017 137 – 142 26 10 May 2017 143 – 150 27 11 May 2017 151 – 157 28 22 June 2017 159 – 163 29 15 August 2017 165 – 169 30 16 August 2017 171 – 176 31 17 August 2017 177 – 181 32 22 August 2017 183 – 186 33 23 August 2017 187 – 192 34 24 August 2017 193 – 196 35 10 October 2017 197 – 199 36 11 October 2017 201 – 203 37 12 October 2017 1 Index to Minutes – 18 October 2016 to 25 June 2020 205 – 208 38 17 October 2017 209 – 213 39 18 October 2017 215 – 220 40 19 October 2017 221 – 225 41 21 November 2017 227 – 233 42 22 November 2017 235 – 247 43 23 November -

Tabled Papers Index

Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory Tabled Papers — Sixth Assembly (1990-1994) INDEX This document allows users to search all papers tabled during the life of the Twelfth Assembly. To access a document, use the Tabled Paper number appearing in the first column of the Index (eg —0001 or 1257). Please note that we are working backwards to digitise our older records and they will be uploaded as they are completed for the previous Assemblies. Should you require a Tabled Paper from a previous Assembly you can contact the Table Office by email on [email protected] Tabled Papers are all documents tabled in the Assembly, including but not limited to: Messages from the Administrator Administrative Arrangements Orders Papers tabled by Members during Assembly debates Explanatory Statements accompanying bills introduced Petitions Warrants Reports on Members’ travel Committee Reports Papers tabled at Estimates Committee hearings Annual reports required by NT and some Commonwealth statutes Coroner’s reports Subordinate legislation Reports to the Assembly from Officers of the Assembly (Ombudsman, Auditor-General, Electoral Commission) Please contact the Table Office if you have any questions on 8946 1447 or 8946 1452. Sixth Assembly - Tabled Papers - page 1 No Description Tabled Date by Revocation of Reserve No. 1372 1 Annual Report 1989-1990, Department of the Legislative Assembly Deemed 04.12.90 2 Message No.1 from the Administrator, Debits Tax Bill 1990 (Serial 9) dated 30 Speaker 05.12.90 March 1990 3 Crown Lands Act, Recommendation under section 103, Revocation of various Deemed 04.12.90 reserves Town of Alice Springs, Reserve Nos. -

The Politics of Euthanasia

The Politics of Euthanasia Robert G. Richardson Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Politics School of History and Politics The University of Adelaide May 2008 Dedicated to my Mother & In memory of Rex Richardson (1996–2003) ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................................................. VII DECLARATION ........................................................................................................................................VIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..........................................................................................................................IX 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 2 WESTERN RESPONSES TO END OF LIFE CHOICE.................................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................ 12 DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................................ 12 SUICIDE AND EUTHANASIA IN THE ANCIENT GREEK PERIOD ....................................................................... 13 SUICIDE AND EUTHANASIA IN ANCIENT ROME ........................................................................................... -

Contents Motion

DEBATES – Wednesday 15 February 2017 CONTENTS MOTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 833 Changes to Committee Membership – Public Accounts Committee and Select Committee on Opening Parliament to the People ......................................................................................................................... 833 TERMINATION OF PREGNANCY LAW REFORM BILL ............................................................................ 833 (Serial 15) ................................................................................................................................................ 833 MOTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 842 Note Statement – Supporting and Growing Jobs .................................................................................... 842 PETITION .................................................................................................................................................... 854 Petition No 7 – Bring Dan Murphy’s to Darwin ........................................................................................ 854 ELECTORAL LEGISLATION AMENDMENT BILL (NO 2) .......................................................................... 854 (Serial 8) ................................................................................................................................................. -

Informing the Euthanasia Debate: Perceptions of Australian Politicians

1368 UNSW Law Journal Volume 41(4) INFORMING THE EUTHANASIA DEBATE: PERCEPTIONS OF AUSTRALIAN POLITICIANS ANDREW MCGEE,* KELLY PURSER,** CHRISTOPHER STACKPOOLE,*** BEN WHITE,**** LINDY WILLMOTT***** AND JULIET DAVIS****** In the debate on euthanasia or assisted dying, many different arguments have been advanced either for or against legal reform in the academic literature, and much contemporary academic research seeks to engage with these arguments. However, very little research has been undertaken to track the arguments that are being advanced by politicians when Bills proposing reform are debated in Parliament. Politicians will ultimately decide whether legislative reform will proceed and, if so, in what form. It is therefore essential to know what arguments the politicians are advancing in support of or against legal reform so that these arguments can be assessed and scrutinised. This article seeks to fill this gap by collecting, synthesising and mapping the pro- and anti-euthanasia and assisted dying arguments advanced by Australian politicians, starting from the time the first ever euthanasia Bill was introduced. I INTRODUCTION Euthanasia attracts continued media, societal and political attention.1 In particular, voluntary active euthanasia (‘VAE’) and physician-assisted suicide * BA (Hons) (Lancaster), LLB (Hons) (QUT), LLM (QUT), PhD (Essex); Senior Lecturer, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. ** BA/LLB (Hons) (UNE), PhD (UNE); Senior Lecturer, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. *** LLB/BBus (Hons) (QUT), BCL (Oxford). **** LLB (Hons) (QUT), DPhil (Oxford), Professor, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology. ***** BCom (UQ), LLB (Hons) (UQ), LLM (Cambridge), PhD (QUT); Professor, Australian Centre for Health Law Research, Faculty of Law, Queensland University of Technology.