February 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, And

College ILttirarjj FROM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ' THROUGH £> VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK COMMISSION. RECORD OF THE ORGANIZATIONS ENGAGED IN THE CAMPAIGN, SIEGE, AND DEFENSE OF VICKSBURG. COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS BY jomsr s. KOUNTZ, SECRETARY AND HISTORIAN OF THE COMMISSION. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1901. PREFACE. The Vicksburg campaign opened March 29, 1863, with General Grant's order for the advance of General Osterhaus' division from Millikens Bend, and closed July 4^, 1863, with the surrender of Pem- berton's army and the city of Vicksburg. Its course was determined by General Grant's plan of campaign. This plan contemplated the march of his active army from Millikens Bend, La. , to a point on the river below Vicksburg, the running of the batteries at Vicksburg by a sufficient number of gunboats and transports, and the transfer of his army to the Mississippi side. These points were successfully accomplished and, May 1, the first battle of the campaign was fought near Port Gibson. Up to this time General Grant had contemplated the probability of uniting the army of General Banks with his. He then decided not to await the arrival of Banks, but to make the cam paign with his own army. May 12, at Raymond, Logan's division of Grant's army, with Crocker's division in reserve, was engaged with Gregg's brigade of Pemberton's army. Gregg was largely outnum bered and, after a stout fight, fell back to Jackson. The same day the left of Grant's army, under McClernand, skirmished at Fourteen- mile Creek with the cavalry and mounted infantry of Pemberton's army, supported by Bowen's division and two brigades of Loring's division. -

Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide

GETTYSBURG: THREE DAYS OF GLORY STUDY GUIDE CONFEDERATE AND UNION ORDERS OF BATTLE ABBREVIATIONS MILITARY RANK MG = Major General BG = Brigadier General Col = Colonel Ltc = Lieutenant Colonel Maj = Major Cpt = Captain Lt = Lieutenant Sgt = Sergeant CASUALTY DESIGNATION (w) = wounded (mw) = mortally wounded (k) = killed in action (c) = captured ARMY OF THE POTOMAC MG George G. Meade, Commanding GENERAL STAFF: (Selected Members) Chief of Staff: MG Daniel Butterfield Chief Quartermaster: BG Rufus Ingalls Chief of Artillery: BG Henry J. Hunt Medical Director: Maj Jonathan Letterman Chief of Engineers: BG Gouverneur K. Warren I CORPS MG John F. Reynolds (k) MG Abner Doubleday MG John Newton First Division - BG James S. Wadsworth 1st Brigade - BG Solomon Meredith (w) Col William W. Robinson 2nd Brigade - BG Lysander Cutler Second Division - BG John C. Robinson 1st Brigade - BG Gabriel R. Paul (w), Col Samuel H. Leonard (w), Col Adrian R. Root (w&c), Col Richard Coulter (w), Col Peter Lyle, Col Richard Coulter 2nd Brigade - BG Henry Baxter Third Division - MG Abner Doubleday, BG Thomas A. Rowley Gettysburg: Three Days of Glory Study Guide Page 1 1st Brigade - Col Chapman Biddle, BG Thomas A. Rowley, Col Chapman Biddle 2nd Brigade - Col Roy Stone (w), Col Langhorne Wister (w). Col Edmund L. Dana 3rd Brigade - BG George J. Stannard (w), Col Francis V. Randall Artillery Brigade - Col Charles S. Wainwright II CORPS MG Winfield S. Hancock (w) BG John Gibbon BG William Hays First Division - BG John C. Caldwell 1st Brigade - Col Edward E. Cross (mw), Col H. Boyd McKeen 2nd Brigade - Col Patrick Kelly 3rd Brigade - BG Samuel K. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of The

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts CITIES AT WAR: UNION ARMY MOBILIZATION IN THE URBAN NORTHEAST, 1861-1865 A Dissertation in History by Timothy Justin Orr © 2010 Timothy Justin Orr Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2010 The dissertation of Timothy Justin Orr was reviewed and approved* by the following: Carol Reardon Professor of Military History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Director of Graduate Studies in History Mark E. Neely, Jr. McCabe-Greer Professor in the American Civil War Era Matthew J. Restall Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Colonial Latin American History, Anthropology, and Women‘s Studies Carla J. Mulford Associate Professor of English *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT During the four years of the American Civil War, the twenty-three states that comprised the Union initiated one of the most unprecedented social transformations in U.S. History, mobilizing the Union Army. Strangely, scholars have yet to explore Civil War mobilization in a comprehensive way. Mobilization was a multi-tiered process whereby local communities organized, officered, armed, equipped, and fed soldiers before sending them to the front. It was a four-year progression that required the simultaneous participation of legislative action, military administration, benevolent voluntarism, and industrial productivity to function properly. Perhaps more than any other area of the North, cities most dramatically felt the affects of this transition to war. Generally, scholars have given areas of the urban North low marks. Statistics refute pessimistic conclusions; northern cities appeared to provide a higher percentage than the North as a whole. -

Leadership and Social Movements: the Forty-Eighters in the Civil War

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES LEADERSHIP AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: THE FORTY-EIGHTERS IN THE CIVIL WAR Christian Dippel Stephan Heblich Working Paper 24656 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24656 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2018 We thank the editor and two referees for very helpful suggestions, as well as Daron Acemoglu, Sascha Becker, Toman Barsbai, Jean-Paul Carvalho, Dora Costa, James Feigenbaum, Raquel Fernandez, Paola Giuliano, Walter Kamphoefner, Michael Haines, Tarek Hassan, Saumitra Jha, Matthew Kahn, Naomi Lamoreaux, Gary Libecap, Zach Sauers, Jakob Schneebacher, Elisabeth Perlman, Nico Voigtländer, John Wallis, Romain Wacziarg, Gavin Wright, Guo Xu, and seminar participants at UCLA, U Calgary, Bristol, the NBER DAE and POL meetings, the EHA meetings, and the UCI IMBS conference for valuable comments. We thank David Cruse, Andrew Dale, Karene Daniel, Andrea di Miceli, Jake Kantor, Zach Lewis, Josh Mimura, Rose Niermeijer, Sebastian Ottinger, Anton Sobolev, Gwyneth Teo, and Alper Yesek for excellent research assistance. We thank Michael Haines for sharing data. We thank Yannick Dupraz and Andreas Ferrara for data-sharing and joint efforts in collecting the Civil War soldier and regiments data. We thank John Wallis and Jeremy Darrington for helpful advice in locating sub-county voting data for the period, although we ultimately could not use it. Dippel acknowledges financial support for this project from the UCLA Center of Global Management, the UCLA Price Center and the UCLA Burkle Center. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

Reminiscences

REMINISCENCES OF THE POLITICAL LIFE OF THE GERMAN-AMERICANS IN BALTIMORE, DURING 1850 — 1860. Reminiscenses OF THE Political Life of the German-Americans in Baltimore during 1850—1860. BY L. P. HENNIGHAUSEN. THE decade from 1850 to 1860 in the political life of the German-Americans in Baltimore is specially interesting. It was a period of independent original thought, of high intellectual activity, of aggressive propaganda, and of great suffering. The older German immigration had quietly adopted the political opinions of their American fellow citizens and according to inclination fell into the ranks of the existing Whig or De- mocratic parties. The political life of the German people before the memorable year of 1848 had been for a long time dormant. The attempt of 1833 to start a revolution in Germany was con- fined to the academic youth and a few literary men and never had a hold on the masses. In 1848 the idea of a liberal par- lamentary government for the German empire, or the formation of a republic, had taken hold of and stirred up the entire Ger- man nation. Want of experience in political party life, lack of organization and excesses of the radical faction, which fright- ened the conservative element, enabled the governments, who still had the control of the army, to regain the ascendency, to crush armed resistance and, a short time thereafter, to inaugurate the so-called reactionary period in Germany which lasted until about the year 1861. Whoever had taken an active part in the revolutionary movement was treated as a criminal. -

First Day Ebook

FIRST DAY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Daddo,Jonathan Bentley | 32 pages | 01 Dec 2013 | ABC Books | 9780733331206 | English | Sydney, Australia First Day PDF Book Confederate Maj. By the end of the three-day battle, they had about men standing, the highest casualty percentage for one battle of any regiment, North or South. Coster's battle line just north of the town in Kuhn's brickyard was overwhelmed by Hays and Avery. Some loans may be eligible for same day funding! Pfanz judges Barlow's decision to be a "blunder" that "ensured the defeat of the corps. These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. Hannah confides in Mr. To the right, Stone's Bucktails, facing both west and north along the Chambersburg Pike, were attacked by both Brockenbrough and Daniel. He immediately dispatched Hancock, commander of the II Corps and his most trusted subordinate, to the scene with orders to take command of the field and to determine whether Gettysburg was an appropriate place for a major battle. They were able to pour enfilading fire from both ends of the cut, and many Confederates considered surrender. No, thank you! Rowley , which Doubleday placed on either end of his line. Savannah 4 episodes, Bianca Pisani The series originated as a short film of the same title which aired in Emmy Award Winning Director hockfilms. Richard Ewell's second division, under Jubal Early, swept down the Harrisburg Road, deployed in a battle line three brigades wide, almost a mile across 1, m and almost half a mile m wider than the Union defensive line. -

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index The Heritage Center of The Union League of Philadelphia 140 South Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 www.ulheritagecenter.org [email protected] (215) 587-6455 Collection 1805.060.021 Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers - Collection of Bvt. Lt. Col. George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index Middle Last Name First Name Name Object ID Description Notes Portrait of Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Abbott was killed on May 6, 1864, at the Battle Abbott Henry L. 1805.060.021.22AP Massachusetts Infantry. of the Wilderness in Virginia. Portrait of Colonel Ira C. Abbott of the 1st Abbott Ira C. 1805.060.021.24AD Michigan Volunteers. Portrait of Colonel of the 7th United States Infantry and Brigadier General of Volunteers, Abercrombie John J. 1805.060.021.16BN John J. Abercrombie. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Captain of the 3rd United States Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel, Assistant Adjutant General of the Volunteers, and Brevet Brigadier Alexander Andrew J. -

35E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle 29 Juin – 9 Juillet 2007 001-006-Debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 2

001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 1 35e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle 29 juin – 9 juillet 2007 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 2 PRÉSIDENT D’HONNEUR Jacques Chavier PRÉSIDENT Jean-Michel Porcheron DÉLÉGUÉE GÉNÉRALE Prune Engler PUBLICATIONS DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE Anne Berrou Prune Engler assistée d’Elise Dansette Sylvie Pras TRADUCTIONS ADMINISTRATION Nathalie Carbonne Arnaud Dumatin MAQUETTE CATALOGUE CHARGÉE DE PRODUCTION Olivier Dechaud Sophie Mirouze GRAPHISME AUTRES PUBLICATIONS CHARGÉ DE MISSION À LA ROCHELLE Antichambre Stéphane Le Garff Olivier Dechaud assisté de Florence Blancho AFFICHE DU FESTIVAL DIRECTION TECHNIQUE Stanislas Bouvier Thomas Lorin BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (PARIS) assisté de David Séropian SITE INTERNET 16 rue Saint-Sabin 75011 Paris Nicolas Le Thierry d’Ennequin Tél.: 33 (0)1 48 06 16 66 COMPTABILITÉ Fax: 33 (0)1 48 06 15 40 Monique Savinaud PHOTOGRAPHIES Email: Régis d’Audeville [email protected] PRESSE Sites internet: matilde incerti ACCUEIL DES PROFESSIONNELS www.festival-larochelle.org assistée d’Andreï Von Kamarowsky Marine Sentin www.myspace.com/festivallarochelle et d’Hervé Dupont assistée de Josiane Roberge et de Sandie Ruchon BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (LA ROCHELLE) PROGRAMMATION VIDÉO Tél. et Fax: 33 (0)5 46 52 28 96 Brent Klinkum ACCRÉDITATIONS Email: assisté de Luc Brou Audrey Tazière [email protected] 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 3 35e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle 29 juin – 9 juillet 2007 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 4 FESTIVALIERS SANS FRONTIÈRES L'exercice éditorialiste exige une distance, un point de vue qui permettraient de survoler les films de cette 35e édition en n'en retenant que l'essentiel. -

From Manassas to Appomattox

From Manassas To Appomattox By James Longstreet FROM MANASSAS TO APPOMATTOX. CHAPTER I. THE ANTE-BELLUM LIFE OF THE AUTHOR. Birth—Ancestry—School-Boy Days—Appointment as Cadet at the United States Military Academy—Graduates of Historic Classes—Assignment as Brevet Lieutenant—Gay Life of Garrison at Jefferson Barracks—Lieutenant Grant’s Courtship—Annexation of Texas—Army of Observation—Army of Occupation—Camp Life in Texas—March to the Rio Grande—Mexican War. I was born in Edgefield District, South Carolina, on the 8th of January, 1821. On the paternal side the family was from New Jersey; on my mother’s side, from Maryland. My earliest recollections were of the Georgia side of Savannah River, and my school-days were passed there, but the appointment to West Point Academy was from North Alabama. My father, James Longstreet, the oldest child of William Longstreet and Hannah Fitzrandolph, was born in New Jersey. Other children of the marriage, Rebecca, Gilbert, Augustus B., and William, were born in Augusta, Georgia, the adopted home. Richard Longstreet, who came to America in 1657 and settled in Monmouth County, New Jersey, was the progenitor of the name on this continent. It is difficult to determine whether the name sprang from France, Germany, or Holland. On the maternal side, Grandfather Marshall Dent was first cousin of John Marshall, of the Supreme Court. That branch claimed to trace their line back to the Conqueror. Marshall Dent married a Magruder, when they migrated to Augusta, Georgia. Father married the eldest daughter, Mary Ann. Grandfather William Longstreet first applied steam as a motive power, in 1787, to a small boat on the Savannah River at Augusta, and spent all of his private means upon that idea, asked aid of his friends in Augusta and elsewhere, had no encouragement, but, on the contrary, ridicule of his proposition to move a boat without a pulling or other external power, and especially did they ridicule the thought of expensive steam-boilers to be made of iron. -

The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War ONLINE APPENDIX

Leadership and Social Movements: The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War ONLINE APPENDIX Christian Dippel* Stephan Heblich September 2, 2020 * University of California, Los Angeles, CCPR, and NBER. University of Bristol, CESifo, ifw Kiel, IZA, and SERC. Table of Contents A Extended Historical Background 4 A1 The 1848{1849 Revolutions in Germany . .4 A2 The Slavery Issue in U.S. Politics 1844{1860 . .6 A3 Additional Historiography of the Role of the Forty-Eighters and the Turner Societies in the 1860 Election and in the Civil War . .9 A4 Selected Biographical Case Studies of Forty-Eighters ................. 12 A4.1 Example of a Journalist . 12 A4.2 Example of an Artist . 13 A4.3 Example of a Turner . 14 A4.4 Example of a Military Man . 15 B Data Appendix 16 B1 The Forty-Eighters ..................................... 16 B2 The Union Army Data . 17 B2.1 Record-Linking Union Army Data to the Full-Count Census . 19 B2.2 Spatial Interpolation Based on Local Enlistment . 23 B3 Inferring Soldiers' Ancestry Using Machine Learning . 25 B4 Historical Town and County Controls . 27 B4.1 Historical County-Level Controls . 28 B4.2 Historical Voting Data . 28 B5 Factors Attracting the Forty-Eighters into Specific Towns . 28 B5.1 Metzler's Map for Immigrants .......................... 28 B5.2 Mapping the Germans to America Shipping Lists into U.S. Towns . 29 B6 Turner Societies ...................................... 29 C Matched Sample Details 31 D Robustness Checks and Additional Results 31 D1 Alternative IV Strategy . 43 2 E Event Study 46 3 A Extended Historical Background A1 The 1848{1849 Revolutions in Germany Somewhat surprised by the revolutionary movement, rulers of smaller German states|what we know as Germany today comprised 39 independent states which were part of the German Confederation| were fast to give in. -

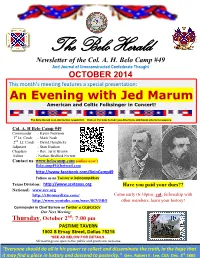

October 2014

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col. A. H. Belo Camp #49 And Journal of Unreconstructed Confederate Thought OCTOBER 2014 This month’s meeting features a special presentation: An Evening with Jed Marum American and Celtic Folksinger in Concert! The Belo Herald is an interactive newsletter. Click on the links to take you directly to additional internet resources. Col. A. H Belo Camp #49 Commander - Kevin Newsom st 1 Lt. Cmdr. - Mark Nash nd 2 Lt. Cmdr. - David Hendricks Adjutant - Stan Hudson Chaplain - Rev. Jerry Brown Editor - Nathan Bedford Forrest Contact us: www.belocamp.com (online now!) [email protected] http://www.facebook.com/BeloCamp49 Follow us on Twitter at belocamp49scv Texas Division: http://www.scvtexas.org Have you paid your dues?? National: www.scv.org http://1800mydixie.com/ Come early (6:30pm), eat, fellowship with http://www.youtube.com/user/SCVORG other members, learn your history! Commander in Chief Barrow on Twitter at CiC@CiCSCV Our Next Meeting: Thursday, October 2nd: 7:00 pm PASTIME TAVERN 1503 S Ervay Street, Dallas 75215 *SEE AD BELOW FOR DETAILS . All meetings are open to the public and guests are welcome. "Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in the hope that it may find a place in history and descend to posterity." Gen. Robert E. Lee, CSA Dec. 3rd 1865 This meeting, Oct. 2nd …. An A.H. Belo Camp 49 SPECIAL EVENT! Come Join us for a very special evening of music and Southern fellowship with American and Celtic Folk singer JED MARUM! There will be a cash bar and CD’s available Surrounding camps are encouraged to come and to bring guests for this FREE EVENT. -

Lincoln's Hungarian Heroes; the Participation of Hungarians in the Civil War, 1861-1865

Lincoln's Hungarian Heroes The Participation of Hungarians in the Civil War 1861-1865 By EDMUND VAS VARY The Hungarian Reformed Federation of America Washington, D. C. THE HUNGARIAN REFORMED FEDERATION OF AMERICA KOSSUTH BUILDING 1726 PENNSYLVANIA AYE., N. W. WASHINGTON, D.O. ^SMsSS& líjjpwm i mPRESIDENT ABRAHAM LINCOLN Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/lincolnshungariaOOvasv LINCOLN'S HUNGARIAN HEROES THE PARTICIPATION OF HUNGARIANS IN THE CIVIL WAR 1861-1865 BY EDMUND VASVARY THE HUNGARIAN REFORMED FEDERATION OF AMERICA WASHINGTON, D. C. 1939 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON March 15, 1939 My dear Mr. Vasvary: I am glad to learn that The Hungarian Re- formed Federation of America is planning to hold com- memorative services on June fourth next in connection with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the battle of Piedmont, Virginia where Major General Julius H. Stahel exemplified such bravery that he later received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Men of Hungarian blood — many of them exiles from their fatherland — rendered valiant service to the cause of the Union. Their deeds of self-sacrifice and bravery deserve to be held in everlasting remembrance. Very sincerely yours, \K4*A*+t^ Jf/u*#^*t£^ Reverend Edmund Vasvary, The Hungarian Reformed Federation of America, 1726 Pennsylvania Avenue, N. W., Washington, D. C. PRESIDENT FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT Xj&i^iw^ tsr^ ££<7 C&uts&^Z- ú^é^ZÍz^ zr^^^c^t/, / / t^&£V€2^lsV~yuc*> ^>£€^^>V~^^ cf£ifC£s*ri-&+<S t C%o^r-*^V. r &v-e^ s?rm^ fe <^&Lc*^ ^^y^^ri^^LJ €^€>^^%r^ /t/e4sisx^e^ Letter of Capt.