Reminiscences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, And

College ILttirarjj FROM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ' THROUGH £> VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK COMMISSION. RECORD OF THE ORGANIZATIONS ENGAGED IN THE CAMPAIGN, SIEGE, AND DEFENSE OF VICKSBURG. COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS BY jomsr s. KOUNTZ, SECRETARY AND HISTORIAN OF THE COMMISSION. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1901. PREFACE. The Vicksburg campaign opened March 29, 1863, with General Grant's order for the advance of General Osterhaus' division from Millikens Bend, and closed July 4^, 1863, with the surrender of Pem- berton's army and the city of Vicksburg. Its course was determined by General Grant's plan of campaign. This plan contemplated the march of his active army from Millikens Bend, La. , to a point on the river below Vicksburg, the running of the batteries at Vicksburg by a sufficient number of gunboats and transports, and the transfer of his army to the Mississippi side. These points were successfully accomplished and, May 1, the first battle of the campaign was fought near Port Gibson. Up to this time General Grant had contemplated the probability of uniting the army of General Banks with his. He then decided not to await the arrival of Banks, but to make the cam paign with his own army. May 12, at Raymond, Logan's division of Grant's army, with Crocker's division in reserve, was engaged with Gregg's brigade of Pemberton's army. Gregg was largely outnum bered and, after a stout fight, fell back to Jackson. The same day the left of Grant's army, under McClernand, skirmished at Fourteen- mile Creek with the cavalry and mounted infantry of Pemberton's army, supported by Bowen's division and two brigades of Loring's division. -

Leadership and Social Movements: the Forty-Eighters in the Civil War

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES LEADERSHIP AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS: THE FORTY-EIGHTERS IN THE CIVIL WAR Christian Dippel Stephan Heblich Working Paper 24656 http://www.nber.org/papers/w24656 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2018 We thank the editor and two referees for very helpful suggestions, as well as Daron Acemoglu, Sascha Becker, Toman Barsbai, Jean-Paul Carvalho, Dora Costa, James Feigenbaum, Raquel Fernandez, Paola Giuliano, Walter Kamphoefner, Michael Haines, Tarek Hassan, Saumitra Jha, Matthew Kahn, Naomi Lamoreaux, Gary Libecap, Zach Sauers, Jakob Schneebacher, Elisabeth Perlman, Nico Voigtländer, John Wallis, Romain Wacziarg, Gavin Wright, Guo Xu, and seminar participants at UCLA, U Calgary, Bristol, the NBER DAE and POL meetings, the EHA meetings, and the UCI IMBS conference for valuable comments. We thank David Cruse, Andrew Dale, Karene Daniel, Andrea di Miceli, Jake Kantor, Zach Lewis, Josh Mimura, Rose Niermeijer, Sebastian Ottinger, Anton Sobolev, Gwyneth Teo, and Alper Yesek for excellent research assistance. We thank Michael Haines for sharing data. We thank Yannick Dupraz and Andreas Ferrara for data-sharing and joint efforts in collecting the Civil War soldier and regiments data. We thank John Wallis and Jeremy Darrington for helpful advice in locating sub-county voting data for the period, although we ultimately could not use it. Dippel acknowledges financial support for this project from the UCLA Center of Global Management, the UCLA Price Center and the UCLA Burkle Center. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

35E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle 29 Juin – 9 Juillet 2007 001-006-Debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 2

001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 1 35e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle 29 juin – 9 juillet 2007 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 2 PRÉSIDENT D’HONNEUR Jacques Chavier PRÉSIDENT Jean-Michel Porcheron DÉLÉGUÉE GÉNÉRALE Prune Engler PUBLICATIONS DIRECTION ARTISTIQUE Anne Berrou Prune Engler assistée d’Elise Dansette Sylvie Pras TRADUCTIONS ADMINISTRATION Nathalie Carbonne Arnaud Dumatin MAQUETTE CATALOGUE CHARGÉE DE PRODUCTION Olivier Dechaud Sophie Mirouze GRAPHISME AUTRES PUBLICATIONS CHARGÉ DE MISSION À LA ROCHELLE Antichambre Stéphane Le Garff Olivier Dechaud assisté de Florence Blancho AFFICHE DU FESTIVAL DIRECTION TECHNIQUE Stanislas Bouvier Thomas Lorin BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (PARIS) assisté de David Séropian SITE INTERNET 16 rue Saint-Sabin 75011 Paris Nicolas Le Thierry d’Ennequin Tél.: 33 (0)1 48 06 16 66 COMPTABILITÉ Fax: 33 (0)1 48 06 15 40 Monique Savinaud PHOTOGRAPHIES Email: Régis d’Audeville [email protected] PRESSE Sites internet: matilde incerti ACCUEIL DES PROFESSIONNELS www.festival-larochelle.org assistée d’Andreï Von Kamarowsky Marine Sentin www.myspace.com/festivallarochelle et d’Hervé Dupont assistée de Josiane Roberge et de Sandie Ruchon BUREAU DU FESTIVAL (LA ROCHELLE) PROGRAMMATION VIDÉO Tél. et Fax: 33 (0)5 46 52 28 96 Brent Klinkum ACCRÉDITATIONS Email: assisté de Luc Brou Audrey Tazière [email protected] 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 3 35e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle 29 juin – 9 juillet 2007 001-006-debut-07 9/06/07 22:55 Page 4 FESTIVALIERS SANS FRONTIÈRES L'exercice éditorialiste exige une distance, un point de vue qui permettraient de survoler les films de cette 35e édition en n'en retenant que l'essentiel. -

The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War ONLINE APPENDIX

Leadership and Social Movements: The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War ONLINE APPENDIX Christian Dippel* Stephan Heblich September 2, 2020 * University of California, Los Angeles, CCPR, and NBER. University of Bristol, CESifo, ifw Kiel, IZA, and SERC. Table of Contents A Extended Historical Background 4 A1 The 1848{1849 Revolutions in Germany . .4 A2 The Slavery Issue in U.S. Politics 1844{1860 . .6 A3 Additional Historiography of the Role of the Forty-Eighters and the Turner Societies in the 1860 Election and in the Civil War . .9 A4 Selected Biographical Case Studies of Forty-Eighters ................. 12 A4.1 Example of a Journalist . 12 A4.2 Example of an Artist . 13 A4.3 Example of a Turner . 14 A4.4 Example of a Military Man . 15 B Data Appendix 16 B1 The Forty-Eighters ..................................... 16 B2 The Union Army Data . 17 B2.1 Record-Linking Union Army Data to the Full-Count Census . 19 B2.2 Spatial Interpolation Based on Local Enlistment . 23 B3 Inferring Soldiers' Ancestry Using Machine Learning . 25 B4 Historical Town and County Controls . 27 B4.1 Historical County-Level Controls . 28 B4.2 Historical Voting Data . 28 B5 Factors Attracting the Forty-Eighters into Specific Towns . 28 B5.1 Metzler's Map for Immigrants .......................... 28 B5.2 Mapping the Germans to America Shipping Lists into U.S. Towns . 29 B6 Turner Societies ...................................... 29 C Matched Sample Details 31 D Robustness Checks and Additional Results 31 D1 Alternative IV Strategy . 43 2 E Event Study 46 3 A Extended Historical Background A1 The 1848{1849 Revolutions in Germany Somewhat surprised by the revolutionary movement, rulers of smaller German states|what we know as Germany today comprised 39 independent states which were part of the German Confederation| were fast to give in. -

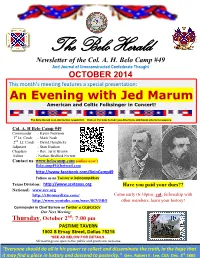

October 2014

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col. A. H. Belo Camp #49 And Journal of Unreconstructed Confederate Thought OCTOBER 2014 This month’s meeting features a special presentation: An Evening with Jed Marum American and Celtic Folksinger in Concert! The Belo Herald is an interactive newsletter. Click on the links to take you directly to additional internet resources. Col. A. H Belo Camp #49 Commander - Kevin Newsom st 1 Lt. Cmdr. - Mark Nash nd 2 Lt. Cmdr. - David Hendricks Adjutant - Stan Hudson Chaplain - Rev. Jerry Brown Editor - Nathan Bedford Forrest Contact us: www.belocamp.com (online now!) [email protected] http://www.facebook.com/BeloCamp49 Follow us on Twitter at belocamp49scv Texas Division: http://www.scvtexas.org Have you paid your dues?? National: www.scv.org http://1800mydixie.com/ Come early (6:30pm), eat, fellowship with http://www.youtube.com/user/SCVORG other members, learn your history! Commander in Chief Barrow on Twitter at CiC@CiCSCV Our Next Meeting: Thursday, October 2nd: 7:00 pm PASTIME TAVERN 1503 S Ervay Street, Dallas 75215 *SEE AD BELOW FOR DETAILS . All meetings are open to the public and guests are welcome. "Everyone should do all in his power to collect and disseminate the truth, in the hope that it may find a place in history and descend to posterity." Gen. Robert E. Lee, CSA Dec. 3rd 1865 This meeting, Oct. 2nd …. An A.H. Belo Camp 49 SPECIAL EVENT! Come Join us for a very special evening of music and Southern fellowship with American and Celtic Folk singer JED MARUM! There will be a cash bar and CD’s available Surrounding camps are encouraged to come and to bring guests for this FREE EVENT. -

February 2014

The Belo Herald Newsletter of the Col. A. H. Belo Camp #49 And Journal of Unreconstructed Confederate Thought February 2014 This month’s meeting features a special presentation: Col. John Geider Gettysburg: A Military Perspective The Belo Herald is an interactive newsletter. Click on the links to take you directly to additional internet resources. Col. A. H Belo Camp #49 Commander - Kevin Newsom st 1 Lt. Cmdr. - Mark Nash nd 2 Lt. Cmdr. - David Hendricks Adjutant - Stan Hudson Chaplain - Rev. Jerry Brown Editor - Nathan Bedford Forrest Contact us: http://belocamp.org [email protected] http://www.facebook.com/BeloCamp49 Follow us on Twitter at belocamp49scv Texas Division: www.texas-scv.org Have you paid your dues?? National: www.scv.org http://1800mydixie.com/ Come early (6:30pm), eat, fellowship with http://www.youtube.com/user/SCVORG other members, learn your history! Commander in Chief Givens on Twitter at CiC@CiCSCV Our Next Meeting: Thursday, February 6th: 7:00 pm La Madeleine Restaurant 3906 Lemmon Ave near Oak Lawn, Dallas, TX *we meet in the private meeting room. All meetings are open to the public and guests are welcome. Commander’s Report Compatriots, This January was a whirlwind of activity. The first gust was the Division Executive Council (DEC) Meeting in Lorena. A hot topic at the DEC meeting was the pledge of allegiance to the federal flag. An opinion was voiced that all camps should be required to recite the pledge before each meeting. This was followed by several minutes of passionate debate. I want to thank Division Commander Holley for re-affirming that it's up to each individual camp to make the decision to recite the pledge. -

Johnson's History of Cooper County

History of Cooper County Missouri by W. F. Johnson Pages 950 - 1000 George Bail (Transcribed by Jim Thoma) George Bail, proprietor of an excellent farm in Palestine Township is one of the substantial farmers and stockmen in that section of Cooper County. He was born in Boonville Aug. 27, 1861, son of Meirad and Gertrude (Stepner) Bail, who in 1873 moved from that city to a farm in Palestine Township, the place now owned and occupied by their son, George, and there established their home. Having been but 12 years of age when his parents moved from Boonville to the farm in Palestine Township, George Bail completed his schooling in the schools of that neighborhood and early became acquainted with the details of farm life. He continued farming there until he was 25 years of age when, in 1886, he went to California, remaining there for two years. In 1888 he returned home and began farming with his brother, renting a farm in partnership, and in 1895, he bought the old home place and has since resided there. Since taking possession of the place Mr. Bail has made extensive improvements. He is the owner of 350 acres of land and in addition to his general farming gives considerable attention to the raising of high grade live stock. Mr. Bail is an independent republican. His parents were among the organizers of the Evangelical church in that neighborhood and he has ever remained a faithful supporter of the same. Sept. 23, 1896, George Bail was married to Mary Muller, who also was born in this county and who died Sept. -

Johnson's History of Cooper County

History of Cooper County Missouri by W. F. Johnson Pages 650 - 700 Alvin J. Bozarth (Transcribed by Laura Paxton) Alvin J Bozarth, a well-known wholesale dealer in butter, eggs, poultry, hides and cream at 415 Chestnut street in Boonville is one of the leading business men of Cooper County. Mr. Bozarth entered business Jan 1 1916 at his present location purchasing the business of the Wilson Produce Co. He mastered his trade under F M Stamper of the F M Stamper CO. at Moberly MO and George Legg of the George Legg Poultry establishment at Mattoon Ill. Since he began business three years ago, Mr. Bozarth has prospered and his trade has yearly grown. The receipts for the three years enumerated successively, were: $98,000, $108,000, and $150,000. He ships his produce to New York, Chicago and other leading markets, shipping in carload lots. Mr. Bozarth deserves much praise and credit for the excellent market he has established for all the countryside bordering Boonville. Bottom of Page 650 Mr. Bozarth was born in Cairo MO, Nov 21 1891 a son of F R and Frances (Robers) Bozarth, both of whom are natives of Monroe County, Missouri and settled in Monroe County in the early days. Mr. and Mrs. F R Bozarth reside at Cairo MO. They are the parents of eight children as follow: Lucy the wife of Albert Snodgrass of Moberly MO; Alvin J, the subject of this sketch; Harry J of Moberly MO; Floyd C of Detroit Michigan; Deston L, of Cairo MO; Pearl, Eulah Mae, and Roy Marshal of Cairo MO. -

Adolf Cluss Und Die Turnbewegung. Vom Heilbronner Turnfest 1846 Ins Amerikanische Exil

Online-Publikationen des Stadtarchivs Heilbronn 19 Adolf Cluss und die Turnbewegung. Vom Heilbronner Turnfest 1846 ins amerikanische Exil. Vorträge des gleichnamigen Symposiums am 28. und 29. Oktober 2005 in Heilbronn. Herausgegeben von Lothar Wieser und Peter Wanner Kleine Schriftenreihe des Archivs der Stadt Heilbronn 54 2007 Stadtarchiv Heilbronn urn:nbn:de:101:1-2014012714766 Die Online-Publikationen des Stadtarchivs Heilbronn sind unter der Creative Commons-Lizenz CC BY-SA 3.0 DE lizenziert. Stadtarchiv Heilbronn Eichgasse 1 74072 Heilbronn Tel. 07131-56-2290 www.stadtarchiv-heilbronn.de Adolf Cluss und die Turnbewegung Kleine Schriftenreihe des Archivs der Stadt Heilbronn Im Auftrag der Stadt Heilbronn herausgegeben von Christhard Schrenk 54 Adolf Cluss und die Turnbewegung 2007 Stadtarchiv Heilbronn Adolf Cluss und die Turnbewegung Vom Heilbronner Turnfest 1846 ins amerikanische Exil Vorträge des gleichnamigen Symposiums am 28. und 29. Oktober 2005 in Heilbronn Herausgegeben von Lothar Wieser und Peter Wanner 2007 Stadtarchiv Heilbronn Erschienen in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Institut für Sportgeschichte Baden-Württemberg e.V., Maulbronn Das Symposium am 28. und 29. Oktober 2005 wurde gefördert durch das Transatlantik-Programm der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus Mitteln des European Recovery Program (ERP) des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Arbeit Redaktion: Lothar Wieser, Martin Ehlers, Michael Krüger und Peter Wanner © Stadtarchiv Heilbronn 2007 Satz: design_idee_erfurt Herstellung: Medien Druck Unterland, Weinsberg Das Werk einschließlich aller Abbildungen ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Stadtarchivs Heilbronn unzulässig und straf- bar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeiche- rung und Bearbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. ISBN 978-3-928990-97-4 Inhalt Zum Geleit ........................................................................................................................