Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beautiful Cubit System I Douglas 2019 the Beautiful Cubit System

The Beautiful Cubit System I Douglas 2019 The Beautiful Cubit System Ian Douglas, B.Sc [email protected] 30 June 2019 Version 1.0.0 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3263864 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Abstract An analysis of the Egyptian Royal cubit, presenting some research and opinions flowing from that research, into what I believe was the original cubit, and how it was corrupted. I show various close arithmetic approximations and multiple ways of getting the divisions of the cubit, as well as some related measures. The cubit also encapsulates the basic components for the metric system. Keywords: Egyptology, metrology, royal cubit, cubit, metre, foot, metric system Contents 1. Introduction 2. Overview of current understanding 3. An alternative origin 4. Different ways of approximating the royal cubit 5. Different ways of getting the cubit divisions 6. Geometry, the Royal Cubit and the metric system 7. Bibliography 1. Introduction The cubit is a well-know ancient measure of length, used around various places in the Middle East and Mediterranean region in the distant past. 1 The Beautiful Cubit System I Douglas 2019 It is allegedly based on the length of a human (male) fore-arm. It is typically measured from the back of the elbow to some point between the wrist and the end of the outstretched middle finger, or in some variants, a point beyond that. The problem with this approach is that everyone’s arm is a different length. If the heights of the dynastic Egyptians is taken as representative, then their arms would have been too short to justify the accepted lengths. -

12 Huggins CAA 1983.Pdf

103 SAXON BUILDI NG MEASUREMENTS P.J.Hu99 ins 27 Grange Court, Waltham ~bbey, ~ssex. Abstract The medieval ~nglish rod of 5.OJ m has been shown to have been in use back to the 6th c~ntury.The sub-divi'sions so fa.r detected are thirds and sixths of this .rod. '1',10 particular a.spects are considered in this paper. The first is vhether the rod was divided further into feet; it is suggested that the manupes-the foot measured by hand-at 15 to the rod is the likely contender. The second aspect concerns building data from r-Juckine. At least 66 Saxon post-hole buildings have been analysed and, provisionally, it appears that 40 were set out using a rod of about 4.65 m and 25 using the 5.03 m rod. Extant rods in the Saxon bomeland likewise have a mean value of 4.65 m suggesting this measure Has brought over by the original Saxon settlers at Bucking. Introduction In a developing sub'ject new ideas are formula.ted and old ideas rightly questioned and possibly discarded. Ne," data may support established hypotheses or change or add to the picture. At any particular time one or hvo aspects of a developing subject will appear to be of special importance in a \vorker t s mind. Such is the position at the present time. The first as~ect of current interest is whether or not the 5.03 m rod, used in the Saxon period, was divided into feet. The second aspect concerns a site '''here two measuring systems appear to have been in use. -

Converting Waste Oil Palm Trees Into a Resource R O G R a M M E P N V I R O N M E N T E

w w w . u n ep. o r g United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552 Nairobi, 00100 Kenya Tel: (254 20) 7621234 Fax: (254 20) 7623927 E-mail: [email protected] web: www.unep.org CONVERTING WASTE OIL PALM TREES INTO A ESOURCE R ROGRAMME P NVIRONMENT E ATIONS N NITED U Copyright © United Nations Environment Programme, 2012 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educa- tional or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiv- ing a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Na- tions Environment Programme concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundar- ies. Moreover, the views expressed do not necessarily represent the decision or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, nor does citing of trade names or commercial processes constitute endorsement. Acknowledgement This document was developed by a team led by Dr. Wan Asma Ibrahim Head of Bioen- ergy Programme, Forest Products Division, Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) under the overall guidance and supervision of Surya Prakash Chandak, Senior Pro- gramme Officer, International Environmental Technology Centre, Division of Technol- ogy, Industry & Economics, United Nations Environment Programme. -

English Customary Weights and Measures

English Customary Weights and Measures Distance In all traditional measuring systems, short distance units are based on the dimensions of the human body. The inch represents the width of a thumb; in fact, in many languages, the word for "inch" is also the word for "thumb." The foot (12 inches) was originally the length of a human foot, although it has evolved to be longer than most people's feet. The yard (3 feet) seems to have gotten its start in England as the name of a 3-foot measuring stick, but it is also understood to be the distance from the tip of the nose to the end of the middle finger of the outstretched hand. Finally, if you stretch your arms out to the sides as far as possible, your total "arm span," from one fingertip to the other, is a fathom (6 feet). Historically, there are many other "natural units" of the same kind, including the digit (the width of a finger, 0.75 inch), the nail (length of the last two joints of the middle finger, 3 digits or 2.25 inches), the palm (width of the palm, 3 inches), the hand (4 inches), the shaftment (width of the hand and outstretched thumb, 2 palms or 6 inches), the span (width of the outstretched hand, from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the little finger, 3 palms or 9 inches), and the cubit (length of the forearm, 18 inches). In Anglo-Saxon England (before the Norman conquest of 1066), short distances seem to have been measured in several ways. -

The English Measurement System

THE ENGLISH MEASUREMENT SYSTEM The measurement system commonly used in the United States today is nearly the same as that brought by the colonists from England. These measures had their origins in a variety of cultures –Babylonian, Egyptian, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, and Norman French. The ancient "digit," "palm," "span" and "cubic" units of length slowly lost preference to the length units "inch," "foot," and "yard." Roman contributions include the use of 12 as a base number (the foot is divided into 12 inches) and the words from which we derive many of our present measurement unit names. For example, the 12 divisions of the Roman "pes," or foot were called unciae. Our words "inch" and "ounce" are both derived from that Latin word. The "yard" as a measure of length can be traced back to early Saxon kings. They wore a sash or girdle around the waist that could be removed and used as a convenient measuring device. The word "yard" comes from the Saxon word "gird" meaning the circumference of a person’s waist. Standardizing various units and combining them into loosely related systems of measurement units sometimes occurred in fascinating ways. Tradition holds that King Henry I decreed that a yard should be the distance from the tip of his nose to the end of his outstretched thumb. The length of a furlong (or furrow-long) was established by early Tudor rulers as 220 yards. This led Queen Elizabeth I to declare in the 16th century, that henceforth the traditional Roman mile of 5000 feet would be replaced by one of 5280 feet, making the mile exactly eight furlongs and providing a convenient relationship between the furlong and the mile. -

Vitruvian Man

Activity 1A: Ratio Calculations: Vitruvian Man Students complete a table of ideal human proportions based on Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic drawing of Vitruvian Man. Students use the ratios to calculate dimensions of body features for different-sized individuals with Vitruvian Man’s proportions. Students measure dimensions of head and height for humans and animated characters and calculate their head : height ratios. Understandings • The relationships between body parts can be expressed mathematically using ratios. • Human body ratios vary. • A person’s or character’s appearance can be altered by varying his or her body ratios. Materials Needed • Optional: Printed or digital images of animated characters with varying body proportions (see Advance Preparation) • Handout 1: Unit Overview • Assessment Checklist: Character Design • Handout 2: Vitruvian Man Proportions • Optional: Proportion Matters slide presentation (see Advance Preparation) • Handout 3: Calculating Vitruvian Man Measurements • Handout 4: Human Head : Height Ratios • Rulers • Images of people and animated characters from Appendix A: Head : Height Proportion Images (one per student) (see Advance Preparation) • Handout 5: Journal Assignment DIGITAL/MEDIA/ARTS: MATHEMATICS 8 PROPORTION MATTERS © Education Development Center, Inc. 2011 1. Optional: Show students animated characters with varying proportions. Display the images of animated characters. Ask students: • What do you notice about the differences in the sizes of these characters’ heads in relation to their bodies? What about the sizes of their facial characteristics, such as eyes and mouths? • What effect do you think these visual properties have on your perception of the character? 2. Introduce the concept of proportion. Tell students that in this unit they will look at how body and facial proportions can be quantified mathematically. -

History of Measurement

History of Measurement by Table of Contents Egyptians 1 Leonardo Da'Vinci 2 Roman Empire 3 Units of Measurement 4 English Standards & King James 5 Units of Measurement 6 French Academy 7 Units of Measurement 8 Pivotal Moments 9 References 10 Cover 11 Egyptians 1 cubit = 6 palms = 24 fingers Palm = 4 fingers Hand = 5 fingers Fist = 6 fingers Span = 14 fingers Rod = 100 cubits 1. Shaftment 2. Hand 3. Palm 4. Span 5. Finger 6. Digit Leonardo Da'Vinci Roman Empire 1 foot = 16 fingers (digitus in Latin) or 12 thumbs (inch in Latin) 1 mile = 1000 paces 1 yard = 1 pace Henry I of England His Foot, Thumb, etc. (inch in Latin) became the standard unit size as established by the Office of Weights and Measures Units of Measurement Length • 12 lines = 1 inch • 12 inches = 1 foot • 3 feet = 1 yard • 1760 yards = 1 mile • 36 inches = 1 yard • 440 yards = quarter mile • 880 yards = half mile • 100 links = 1 chain • 10 chains = 1 furlong • 8 furlongs = 1 mile • 4 inches = 1 hand • 22 yards = 1 chain • 5.5 yards = 1 rod, pole or perch • 4 poles = 1 chain • 40 poles = 1 furlong King James Bible Biblical Units of Measurement • Bath = 5.8 gallons Cubit = 17 – 21 inches Ephah = 20 quarts Farthing = ¼ cents Gerah = .02 ounces Hin = 1 gallon Homer = 58 gallons Mina = 1.26 pounds Mite = 1/8 cents Omer = 2 quarts Penny = 16 cents ■ Pound = 100 shekels or 16 dollars Shekel = .4 ounces Span = 9 inches Talent = 75 pounds French Academy of Science Rather than based on human proportions and ratios, Metric system’s: • length (miter) was based on the dimensions of the Earth (one ten- millionth of the distance from the equator to the North Pole) • mass (kilogram) was based on water with volume of 1 liter • temperature based on boiling point and freezing point of water. -

Ancient Egyptian Cubits – Origin and Evolution

Ancient Egyptian Cubits – Origin and Evolution by Antoine Pierre Hirsch A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto © Copyright by Antoine Pierre Hirsch 2013 i Ancient Egyptian Cubits – Origin and Evolution Antoine Pierre Hirsch Doctor of Philosophy Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This thesis suggests that prior to Ptolemaic and Roman times, ancient Egypt had two distinct and parallel linear systems: the royal system limited to official architectural projects and land measurements, and a great (aA) system used for everyday measurements. A key 1/3 ratio explains ancient Egyptian linear measurements and their agricultural origin. Emmer is 1/3 lighter than barley, consequently, for an equal weight, a container filled with emmer will be 1/3 greater than a container filled with barley. The lengths derived from both containers share the same 1/3 ratio. The second chapter, Previous Studies, lists the work of scholars involved directly or indirectly with ancient Egyptian metrology. The third chapter, The Royal Cubit as a Converter and the Scribe’s Palette as a Measuring Device, capitalizes on the colour scheme (black and white on the reproduction of Appendix A) appearing on the Amenemope cubit artifact to show the presence of two cubits and two systems: the black (royal system) and the white (great [aA] system) materialized by the scribe's palette of 30, 40, and 50 cm. The royal cubit artifacts provide a conversion bridge between the royal and the great systems. The information derived from the visual clues on the Amenemope cubit artifact are tested against a database of artifacts scattered in museums around the world. -

African Art at the Portuguese Court, C. 1450-1521

African Art at the Portuguese Court, c. 1450-1521 By Mario Pereira A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Mario Pereira VITA Mario Pereira was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1973. He received a B.A. in Art History from Oberlin College in 1996 and a M.A. in Art History from the University of Chicago in 1997. His master’s thesis, “The Accademia degli Oziosi: Spanish Power and Neapolitan Culture in Southern Italy, c. 1600-50,” was written under the supervision of Ingrid D. Rowland and Thomas Cummins. Before coming to Brown, Mario worked as a free-lance editor for La Rivista dei Libri and served on the editorial staff of the New York Review of Books. He also worked on the curatorial staff of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum where he translated the exhibition catalogue Raphael, Cellini and a Renaissance Banker: The Patronage of Bindo Altoviti (Milan: Electa, 2003) and curated the exhibition Off the Wall: New Perspectives on Early Italian Art in the Gardner Museum (2004). While at Brown, Mario has received financial support from the Graduate School, the Department of History of Art and Architecture, and the Program in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies. From 2005-2006, he worked in the Department of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design. In 2007-2008, he received the J. M. Stuart Fellowship from the John Carter Brown Library and was the recipient of an Andrew W. -

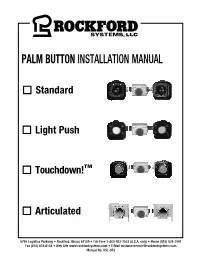

Palm Button Ksl073

PALM BUTTON INSTALLATION MANUAL o Standard o Light Push ™ o Touchdown! o Articulated 5795 Logistics Parkway • Rockford, Illinois 61109 • Toll-Free 1-800-922-7533 (U.S.A. only) • Phone (815) 874-7891 Fax (815) 874-6144 • Web Site www.rockfordsystems.com • E-Mail [email protected] Manual No. KSL-073 TABLE OF CONTENTS Palm Buttons SECTION 1—IN GENERAL ......................................................................................................................................................................3-4 SE CTION 2—OSHA AND ANSI REQUIREMENTS .....................................................................................................................................5-7 SECTION 3—ASSEMBLIES ...................................................................................................................................................................8-13 Standard Assemblies ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Light-Push Assemblies ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Touchdown!™ Assemblies ............................................................................................................................................................10-11 Articulated Assemblies ..................................................................................................................................................................12-13 -

Brief History and Use of the ENGLISH and METRIC SYSTEMS of MEASUREMENT with a CHART of the MODERNIZED METRIC SYSTEM

AUG 13 1971 -^4 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE 161670 C. R. SMITH, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS / a. v. astin, Director Special Publication 304A. Issued 1968. lUj h Brief History and Use of THE ENGLISH AND METRIC SYSTEMS OF MEASUREMENT with a CHART OF THE MODERNIZED METRIC SYSTEM "Weights and measures may be ranked among the necessaries of life to every individual of human society. They enter into the eco- nomical arrangements and daily concerns of every family. They are necessary to every occupation of human industry; to the distribution and security of every species of property; to every transaction of trade and commerce ; to the labors of the husbandman ; to the in- genuity of the artificer; to the studies of the philosopher ; to the researches of the antiquarian, to the navigation of the mariner, and the marches of the soldier; to all the exchanges of peace, and all the operations of war." —JOHN QUINCY ADAMS When the American Colonies sepa- sembly of France on May 8, 1790, of the length of a great circle of the rated from the mother country to to enact a decree, sanctioned by Louis earth. This idea found favor with the assume among the nations of the XVI, which called upon the French French philosophers at the time of the earth a separate and individual sta- Academy of Sciences in concert with French Revolution, men who were tion, they retained, among other the Royal Society of London to "de- generally opposed to any vestige of things, the weights and measures duce an invariable standard for all of monarchical authority and preferred that had been used when they were the measures and all weights." Hav- a standard based on a constant of colonies, namely, the weights and ing already an adequate system of nature. -

Section 02930 – Palm Tree Salvage and Planting

The University of Arizona Manual of Design and Specification Standards DIVISION 2 – SITEWORK Section 02930 – Palm Tree Salvage and Planting Introduction This section contains standards for the identification, removal, storage and replanting of existing palm trees on site. Part 1 - General Create a reference sheet for identification of trees to be salvaged. Provide backflow prevention devices for the temporary irrigation system if required by governing codes. Holding Yard: The holding yard for this project will be on the project site, as indicated on the drawings. Water shall be provided by the Contractor. Identification of salvage material The contractor, Architect and Owner's representatives will determine the final selection of salvage specimens based on specimens already identified, current health, accessibility, viability and appearance. These trees shall be final-tagged with colored tape in conspicuous locations, irrigated, and fenced with temporary construction fence to avoid construction damage until they are removed. Contractor is not to remove or work on any salvage material until after the Owner, or designated agent, has determined the limits of the salvage and work area, and has given the Contractor written consent to proceed. Removal of salvage material Description of Work: The Contractor shall provide all labor, tools and materials necessary to remove salvage plants from the ground, frond- and rootball-protect them (when required) and transport them to the holding yard. If it is determined that any of the trees to be transplanted can be immediately located to their new location, the Contractor may do so, but must water, maintain and protect the trees during construction. If any trees are to be installed directly onto another site on UA property, the final site will need to be Bleu staked.