He Aha Te Mea Nui O Te Ao What Is the Mo Important Thing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAG Magazine

SPECIAl ISSUE CONTENTS SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE COVER: THE ART OF GAG A retrospective celebration of GAG and a peek into our future. PAGE 20 5 // Musings from the Editrix 6 // Back Talk 8 // Gagging On with special guest Chiffon Dior LIFE 10 // Libations by Candace Collins 12 // Ask Edna Jean 14 // Voices Trans* Drag by Freddy Prinze Charming 72 // Drag-o-sphere 74 // Spotlight: Fans ART 16 // The Art of Drag: The Making of a King Documentary An interview with woman behind the kings, Nicole Miyahara. 66 // Extravaganza The Austin International Drag Festival GAG sits down with the mastermind behind the world’s first 4 day drag festival. BRANDI AMARA SKYY EDITIRX PAUL MICHAEL ARMSTRONG CREATIVE DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTORS Candace Collins Chiffon Dior Freddy Prinze Charming Edna Jean Robinson PHOTOGRAPHERS Alex Craddock Austin Young AJ Bates photography Cher Musico/Roots Photography Edwin Irizarry Gabe King Photography Jose A. Guzman Colon Kristofer Reynolds of kristoferreynolds.com Marcelo Cantu Photography Mathu Anderson Mei Na Nicole Miyahara Photography by Suri Rosemary Photography Robert Stahl musings from the editirx This issue of GAG is special not only because we are celebrating our second birthday, but because we’re in the middle of a growth spurt. We’ve outgrown some things . Departments like News, Music, Library, DID (Dipping into Drag). And grown into others . Voices where YOU write the story; The Art of Drag where we highlight others like us who are creating spectacular things; and - my personal favorite - Spotlight where we dedicate the last page(s) of the magazine to shining the spotlight on those who make us stars - the fans. -

ISSUE 7.2.QXD 10/8/04 1:22 Pm Page 1

1 FINAL ISSUE 7.2.QXD 10/8/04 1:22 pm Page 1 CELEBRATING A FABULOUS LIFESTYLE FABULOUFABULOUUtterly SS NEWS REVIEWS EVENTS MISS HOUSE OF DRAG Lynn Daniels FREE MAGAZINE Issue 7 1 FINAL ISSUE 7.2.QXD 10/8/04 1:22 pm Page 2 There’s SOMETHING about Photos with tahnaks to Georgina 1 FINAL ISSUE 7.2.QXD 10/8/04 1:23 pm Page 3 2 1 FINAL ISSUE 7.2.QXD 10/8/04 1:23 pm Page 4 UtterlyFABULOUS WELCOME TO Utterly FABULOUS NEWS with editor Vicky Lee ON THE COVER LAST EDITION OF THIS MAGAZINE Model – Lynn Daniels This is the 7th issue of Utterly FABULOUS. Unfortunately it is Hair and make-up – the also last edition. The magazine has been very successful for advertisers. Readers have stripped stockists, devouring each Pandora De’Pledge Image Works issue. However the financial balance between income and pro- Body Paint – The Image Works team duction, printing and distribution costs have never balanced and are not improving. Thank you to everyone that has contributed Photography – Bob Tanner to this magazine. Most especially for the photo features by for Image Works Pandora De Pledge and the support of my good friend Steffan. Graphics - Titch for Image Works SAD LOSS OF RAY RICE Utterly FABULOUS This magazine was inspired by Ray Rice... Ray passed away on © Copyright 2004 27-7-04 our thoughts and love is with Chris, his partner and our The WayOut Publishing Co Ltd good friend. Ray believed that, following in the footsteps of other All rights reserved niche communities, and with wide support of advertisers and sub- scribers, Utterly FABULOUS could become a nationwide FREE Published and Distributed by : magazine bringing awareness of the fabulous transgender lifestyle WayOut Publishing to the widest range of people possible. -

Rupaul's Drag Race from Screens To

‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets Max Mehran A Thesis in The Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) at Concordia University Montréal, Quebec, Canada January 2020 Ó Max Mehran, 2020 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Max Mehran Entitled: ‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Film Studies) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ________________________________ Chair Luca Caminati ________________________________Examiner Haidee Wasson ________________________________Examiner Glyn Davis ________________________________Supervisor Kay Dickinson Approved by ________________________ Graduate Program Director Luca Caminati ________________________ Dean of Faculty Rebecca Duclos Date: January 20th, 2020 iii ABSTRACT ‘Tens, Tens, Tens Across the Board’: Representation, Remuneration, and Repercussion – RuPaul’s Drag Race from Screens to Streets Max Mehran Since its inception, RuPaul’s Drag Race (Drag Race) (2009-) has pitted drag queens against each other in a series of challenges testing acting, singing, and sewing skills. Drag Race continues to become more profitable and successful by the year and arguably shapes cultural ideas of queer performances in manifold ways. This project investigates the impacts of exploitative labour practices that emerge from the show, the commodification of drag when represented on screen, and how the show influences drag and queer performances off screen. -

ANTI-Gay Animus Hits New Low

Dolly’s 9-5 Australia’s leading gay and lesbian newspaper page 33 Est. 1979 ONLINE starobserver.com.au ISSUE 1143 Friday 28 September 2012 FACEBOOK Star Observer TWITTER @star_observer ‘Outlaw gay sex’ ANTI-GAY ANIMUS HITS NEW LOW >> NATIONAL rather than a religious one. BENN DORRINGTON He said he had expected the Labor Party to oppose his views but challenged the Liberal Political leaders and gay rights advocates have Party. condemned comments from a consultant “They are so happy to wave the Catholic psychologist and ACT election candidate who flag but they run a mile when this issue comes believes gay sex should be outlawed. up because they’re uncomfortable with it, I Independent candidate for Molonglo, Philip suppose, or they are too weak to deal with it,” Pocock, published his views on sexuality he said. and marriage while answering an election Existing media reports have also attracted questionnaire for the Archdiocese of Canberra many critical comments online about his and Goulburn. views, which Pocock said he had expected. In his response, Pocock wrote that “There’s a basic sort of insecurity with governments should manage “distortions of everyone about sexuality, it’s a primal thing sexuality” including masturbation, oral sex, so people do become entrenched about it and sodomy and sex before marriage. it’s hard for them to be neutral, they become “Indeed I believe sodomy of man or woman emotionally reactive,” he said. should be regarded as a criminal offence “They’re not surprising, to me it’s indicative and while people do not have the right to go of someone who is, for whatever reason, ‘poofter bashing’.. -

E Past, Present and Future of Drag in Los Angeles

Rap Duo 88Glam embrace Hip-Hop’s fearlessness • Museum Spotlights Ernie Barnes, Artist and Athlete ® MAY 24-30, 2019 / VOL. 41 / NO. 27 / LAWEEKLY.COM Q e Past,UEENDOM Present and Future of Drag in Los Angeles BY MICHAEL COOPER AND LINA LECARO 2 WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM | - , | LA WEEKLY L May 24 - May 30, 2019 // Vol. 41 // No. 27 // laweekly.com 3 LA WEEKLY LA Explore the Country’s Premier School of Archetypal and Depth Psychology Contents - , | | Join us on campus in Santa Barbara WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM Friday, June 7, 2019 The Pacifica Experience A Comprehensive One-Day Introduction to Pacifica’s Master’s and Doctoral Degree Programs Join us for our Information Day and learn about our various degree programs. Faculty from each of the programs will be hosting program-specific information sessions throughout the day. Don't miss out on this event! Pacifica is an accredited graduate school offering degrees in Clinical Psychology, Counseling Psychology, the Humanities and Mythological Studies. The Institute has two beautiful campuses in Santa Barbara nestled between the foothills and the Pacific Ocean. All of Pacifica’s degree programs are offered through monthly three-day learning sessions that take into account vocational, family, and other commitments. Students come to Pacifica from diverse backgrounds in pursuit of an expansive mix of accademic, professional, and personal goals. 7 Experience Pacifica’s unique interdisciplinary degree programs GO LA...4 FILM...16 led by our renowned faculty. Celebrate punk history, explore the NATHANIEL BELL explores the movies opening Tour both of our beautiful campuses including the Joseph Campbell Archives and the Research Library. -

House of Yes Alice

Margo MacDonald • Dmanda Tension • Roy Mitchell esented by PinkPlayMags www.thebuzzmag.ca Pr House of Yes Brooklyn’s Party Central Alice Bag For daily and weekly event listings visit Advocating Through Music JUNE 2020 / JULY 2020 *** free *** TLC Pet Food Proudly Supports the LGTBQ Community Order Online or by Phone Today! TLCPETFOOD.COM | 1•877•328•8400 2 June 2020 / July 2020 theBUZZmag.ca theBUZZmag.ca June 2020 / July 2020 3 Issue #037 The Editor Planning your Muskoka wedding? Make it magical Greetings and Salutations, at our lakeside resort in Ontario. Happy Pride! Although we’re in a time of change and Publisher + Creative Director uncertainty, we still must remain hopeful for a brighter future, Antoine Elhashem and we’re here to offer some uplifting, and positive stories to Editor-in-Chief kick start your summer. Bryen Dunn Art Director Feature one spotlights the incredible work of Brooklyn’s House Mychol Scully of YES collective, an incubator for the creation of awesome parties, cabaret shows, and outrageous events. While their General Manager live events are notorious, they too have had to move into Kim Dobie the digital world, where they’ve been hosting Saturday night Call +1(800)461-0243 or visit MuskokaWeddingVenues.com Sales Representatives interactive dance parties, deep house yoga, drag shows, Carolyn Burtch, Darren Stehle burlesque and dance classes, and their video project, HoY Events Editor TV. Our writer, Raymond Helkio, caught up with HoY to find Sherry Sylvain out what’s up, and he also attended one of their online yoga Counsel classes, which apparently was quite tantalizing. -

Family Time Gone Awry: Vogue Houses and Queer Repro-Generationality at the Intersection(S) of Race and Sexuality

Mathias Klitgård Family Time Gone Awry: Vogue Houses and Queer Repro-Generationality at the Intersection(s) of Race and Sexuality Desintegración de los tiempos familiares: el voguing y la reproducción generacional queer en la encrucijada entre raza y sexualidad A desnaturalização do tempo da família: casas Vogue e repro-geraciona- lidade queer na interseção de raça e sexualidade Mathias Klitgård Network for Gender Research, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway Received 15 November 2017; accepted 18 June 2018 Available online 4 February 2019 Abstract: The paper at hand interrogates the queer temporal politics of “houses” in the ballroom and voguing scene. Houses constitute the axiomatic unit of this community marked by racial and sexual marginalisation and as such create alternative familial relations between members in response to rejections from the biological family and society in general. Mirroring the traditional family institution, vogue houses not only become a source of protection, care, trust and knowledge; their very structure, I argue, induces a queer repro-generational time. Countering the sequential heteronormative time of lifetime milestones and age-fitting achievements, the queer time of voguing is a temporal disidentification that jumbles around and constructively misappropriates generational and reproductive imperatives. In doing this, the politics of voguing opens the horizon of possible futures: it is a spark of embodied resistance with a queer utopian imaginary. Keywords: Voguing; Queer Theory; Critical Race Theory; Time Studies; Subcultures Correo electrónico: [email protected] Debate Feminista 57 (2019), pp. 108-133 ISSN: 0188-9478, Año 29, vol. 57 / abril-septiembre de 2019 / http://doi.org/10.22201/cieg.2594066xe.2019.57.07 © 2019 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de Género. -

The Gentrification of Drag

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-16-2018 The Gentrification of Drag Kyle Kucharski Cuny Graduate School of Journalism How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/294 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Gentrification of Drag How drag refuses to lose its edge in mainstream entertainment By Kyle Kucharski Drag culture is blowing up the mainstream. What has historically been a queer subculture relegated to the nightlife world is now an emerging arena of entertainment on primetime television. Reality TV shows like “RuPaul’s Drag Race” have changed the drag landscape forever, bringing it into the center of the cultural conversation, where it can be made into family-friendly, PG-13 programming. An ever-growing thirst for more drag content means more opportunities for performers to make careers, more money for those performers and more varied and dynamic art. But what is the cost of the commercial monetization of an audacious, queer form of performance born on the margins of society and fueled by the underground? In response to this, a growing community of performers—many of them quite new to drag—have created a space for their own type of art, one that attempts to keep drag underground. Their work suggests that if the value of drag lies in its power to shock and to provide a dissenting critique on heterosexual, cisgender culture, its power as a subversive form of art is lost when its mass-produced and inevitably sanitized. -

1 - ISSUE 3.QXD 6/8/03 12:59 PM Page 1

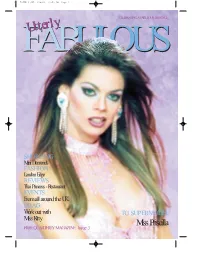

1 - ISSUE 3.QXD 6/8/03 12:59 PM Page 1 CELEBRATING A FABULOUS LIFESTYLE FABFABULOUUtterly ULOUSS SHOPPING Mini Diamonds FASHION London Edge REVIEWS Thai Princess - Restaurant EVENTS From all around the UK DRAG Work out with TG SUPERMODEL Miss Kitty Miss Priscilla FREE QUARTERLY MAGAZINE Issue 3 1 - ISSUE 3.QXD 6/8/03 12:59 PM Page 2 1 - ISSUE 3.QXD 6/8/03 12:59 PM Page 3 UtterlyFABULOUS ON THE COVER WELCOME TO Utterly FABULOUS Photography : Bob Tanner Well it’s April and I feel I am coming out from hibernation after a for Image Works winter of working every waking hour on the 11th edition of The Hair & Make-up, Styling : Tranny Guide at the same time as this edition of Pandora De’Pledge Utterly FABULOUS while also preparing for the WayOut Club’s www.pandoradepledge.com 10th Birthday year. Model : Priscilla 11th Tranny Guide available in April The all new Tranny Guide will be available in April, (so go on, Utterly FABULOUS get YOUR order in now). I can assure you that you will find a © Copyright 2003 big difference to any edition you may have seen before. After The WayOut Publishing Co Ltd achieving the 10th edition milestone, it came to me that after All rights reserved years presenting advice in my “WayOut of the Closet” section there are now many readers that are “Wayout of the closet” Published and Distributed by : with tips of their own to pass on. I asked my email contacts for WayOut Publishing pictures and answers to 14 probing questions. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Rupaul's Drag Race

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. ii While most scholars analyze RuPaul’s Drag Race primarily through content analysis of the aired television episodes, this dissertation combines content analysis with ethnography in order to connect the television show to tangible practices among fans and effects within drag communities. -

ISSUE 2.QXD 13/1/03 5:25 PM Page 3

1 - ISSUE 2.QXD 13/1/03 5:25 PM Page 3 CELEBRATING A FABULOUS LIFESTYLE FABFABULOUSUtterly ULOUS CHRISTMAS TS SUPERMODEL How will you spend yours? Sexational FASHION Oh what a Pantomime Superstar REVIEWS Restaurants & theatres Miss Natasha EVENTS Reviews past and future, From all around the UK DRAG Life is never a drag for ‘Archers Gurl’ Miss Darcy FREE MAGAZINE Issue 2 1 - ISSUE 2.QXD 13/1/03 5:25 PM Page 4 1 - ISSUE 2.QXD 13/1/03 5:26 PM Page 5 UtterlyFABULOUS ON THE COVER WELCOME TO Utterly FABULOUS Photography : Bob Tanner Thank you so much for your wonderful response to the first edition of this for Image Works magazine. From your letters and emails it is clear that you are all agreed that Graphics : Titch for Image Works the new magazine is ... Utterly FABULOUS. Hair & Make-up, Styling : Your messages were truly motivating and have spurred us to increase the Pandora De’Pledge number of pages from 16 to 24 and to increase the size of our print run to www.pandoradepledge.com the highest circulation of any mag in the TG world. We are increasing our Model : Natasha endeavours to get support from main stream business who should be taking the transgender market more seriously. With this support we will be able to continue to provide a free ALL inclusive magazine that aims to support and Utterly FABULOUS promote ALL events and ALL opportunities on the TG scene throughout the UK. © Copyright 2002 THANK YOU TO ALL OUR CONTRIBUTORS who have supplied such The WayOut Publishing Co Ltd terrific help, pictures and reviews. -

This PDF Contains the Complete Keywords Section of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, Volume 1, Numbers 1–2

This PDF contains the complete Keywords section of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, Volume 1, Numbers 1–2. Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/tsq/article-pdf/1/1-2/232/485677/19.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 KEYWORDS Abstract This section includes eighty-six short original essays commissioned for the inaugural issue of TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly. Written by emerging academics, community-based writers, and senior scholars, each essay in this special issue, ‘‘Postposttranssexual: Key Concepts for a Twenty- First-Century Transgender Studies,’’ revolves around a particular keyword or concept. Some con- tributions focus on a concept central to transgender studies; others describe a term of art from another discipline or interdisciplinary area and show how it might relate to transgender stud- ies. While far from providing a complete picture of the field, these keywords begin to elucidate a conceptual vocabulary for transgender studies. Some of the submissions offer a deep and resilient resistance to the entire project of mapping the field terminologically; some reveal yet-unrealized critical potentials for the field; some take existing terms from canonical thinkers and develop the significance for transgender studies; some offer overviews of well-known methodologies and demonstrate their applicability within transgender studies; some suggest how transgender issues play out in various fields; and some map the productive tensions between trans studies and other interdisciplines. Abjection ROBERT PHILLIPS Abjection refers to the vague sense of horror that permeates the boundary between the self and the other. In a broader sense, the term refers to the process by which identificatory regimes exclude subjects that they render unintelligible or beyond classification.