Fire Operations in the Wildland/Urban Interface S-215

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary

Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary CIFFC Training Working Group December 10, 2020 i Preface The Canadian Wildland Fire Glossary provides the wildland A user's guide has been developed to provide guidance on fire community a single source for accurate and consistent the development and review of glossary entries. Within wildland fire and incident management terminology used this guide, users, working groups and committees can find by CIFFC and its' member agencies. instructions on the glossary process; tips for viewing the Consistent use of terminology promotes the efficient glossary on the CIFFC website; guidance for working groups sharing of information, facilitates analysis of data from and committees assigned ownership of glossary terms, disparate sources, improves data integrity, and maximizes including how to request, develop, and revise a glossary the use of shared resources. The glossary is not entry; technical requirements for complete glossary entries; intended to be an exhaustive list of all terms used and a list of contacts for support. by Provincial/Territorial and Federal fire management More specifically, this version reflects numerous additions, agencies. Most terms only have one definition. However, deletions, and edits after careful review from CIFFC agency in some cases a term may be used in differing contexts by staff and CIFFC Working Group members. New features various business areas so multiple definitions are warranted. include an improved font for readability and copying to word processors. Many Incident Command System The glossary takes a significant turn with this 2020 edition Unit Leader positions were added, as were numerous as it will now be updated annually to better reflect the mnemonics. -

Doi105-Archived.Pdf

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Certification of Position Approval for Retirement Under 5 use§ 8336(c) and§ 8412(d) [ x] Approved under the Civil Service Retirement System, 5 USC§ 8336(c) [ x] Approved under the Federal Employees Retirement System, 5 USC§ 8412(d) Category of Coverage: Primary/Rigorous (Firefighter), Bureau: Any DOI Bureau may use tru.s Standard PD and must use the Standard PD Number Classification Title: Range/Forestry Technician (Fire) Organization Title: Senior Wildland Firefighter Standard Position Number: DO1105 Series and Grade: GS-0455/0462-04/05 RECOMMENDATION FOR COVERAGE: Primary/Rigorous Firefighter coverage is recommended under both CSRS and FERS. This position is located on a wildland fire crew as.a senior crewmember within the fire management organization. The purpose of the position is wildland fire suppression/management/control, as a specialized firefighter on an engine, helitack module, or hand crew with responsibility for the operation and maintenance of specialized tools or equipment. Other wildland fire related duties may involve fire prevention, patrol, detection, or prescribed burning. The incumbent may be assigned for varying periods of time into one or more types of positions within the wildfire program where the individual's specialized skills are required. Primary duties are directly connected with the control and extinguishment of fires and/or maintaining and using firefighter apparatus and equipment. The duties of this position are so rigorous that employment is limited to young and physically vigorous individuals who must meet established age and physical qualification requirements. .. a4..zo10 Date ~ - 5 -/~ T Date ARCHIVED Date ~/cJro E, Chief, Branch ofWildland Fire Management, BIA Date 1 . -

Humboldt County Fire Services

Humboldt County Fire Services FIRE CHIEFS' ASSOCIATION OF HUMBOLDT COUNTY Annual Report 2011 To: Humboldt County Board of Supervisors An overview of the Humboldt County Fire Service of 2011 The Fire Service in Humboldt County continues to grow in a positive direction, constantly working towards the goal of promoting county‐wide adoption of procedures and policies through the Fire Chief’s Association with input and regulation from the various groups with‐in such as the Training Instructors, Fire Prevention Officers and the Fire/Arson Investigation Unit. This positive and forward direction is an indication of the great working relationships that have developed among the various departments over the years, and that continues to improve, a feat that is not easy in such a rural setting. These relationships have allowed the fire agencies to foster a team approach both from an operational and an administrative stand point. The effort of forming fire districts for some of the volunteer fire companies with‐in the county, along with the modification of district boundaries in an attempt to provide a better system of protection for many of the Counties’ residents, continues with the help of the Fire Safe Council and County Planning with the support of the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors. The Fire Chief’s Association would like to acknowledge their appreciation of that consideration and support from the Board. At the same time the Chief’s Association recognizes that the future of the fire service in Humboldt County is dependent upon the Board’s continued support. With fees now being levied by the State in the way of “Fire Prevention Fees” to the residents residing in State Responsibility Areas, there is major concern that funding for many of the rural departments will suffer which makes support by the Board of Supervisors a critical factor in their very survival. -

Oregon Department of Forestry

STATE OF OREGON POSITION DESCRIPTION Position Revised Date: 04/17/2019 This position is: Classified Agency: Oregon Department of Forestry Unclassified Executive Service Facility: Central Oregon District, John Day Unit Mgmt Svc - Supervisory Mgmt Svc - Managerial New Revised Mgmt Svc - Confidential SECTION 1. POSITION INFORMATION a. Classification Title: Wildland Fire Suppression Specialist b. Classification No: 8255 c. Effective Date: 6/03/2019 d. Position No: e. Working Title: Firefighter f. Agency No: 49999 g. Section Title: Protection h. Employee Name: i. Work Location (City-County): John Day Grant County j. Supervisor Name (optional): k. Position: Permanent Seasonal Limited duration Academic Year Full Time Part Time Intermittent Job Share l. FLSA: Exempt If Exempt: Executive m. Eligible for Overtime: Yes Non-Exempt Professional No Administrative SECTION 2. PROGRAM AND POSITION INFORMATION a. Describe the program in which this position exists. Include program purpose, who’s affected, size, and scope. Include relationship to agency mission. This position exists within the Protection from Fire Program, which protects 1.6 million acres of Federal, State, county, municipal, and private lands in Grant, Harney, Morrow, Wheeler, and Gilliam Counties. Program objectives are to minimize fire damage and acres burned, commensurate with the 10-year average. Activities are coordinated with other agencies and industry to avoid duplication and waste of resources whenever possible. This position is directly responsible to the Wildland Fire Supervisor for helping to achieve District, Area, and Department-wide goals and objectives at the unit level of operation. b. Describe the primary purpose of this position, and how it functions within this program. -

PASS / FAIL Firefighter II NFPA 1001, 2013 Edition Practical Skills Test JPR

CANDIDATE # Firefighter II NFPA 1001, 2013 Edition Station #: FF2-1 Practical Skills Test JPR: NFPA 1001 6.3.4 First Second Identify and Protect Evidence of Fire Cause Attempt Attempt Pass Fail Pass Fail 1 Secures the scene using barriers and/or guards Recognizes potential evidence 2 Item #1 3 Item #2 4 Item #3 Evaluator must ask: “What steps should be taken to avoid disturbing the 5 evidence you have identified?” Accept any answer that includes: Don’t touch it Keep hose lines and personnel away from it Avoid use of excessive water Don’t move it unnecessarily Evaluator states: “With the materials you have available, show me how you would 6 protect these items of evidence from being destroyed.” Covers foot prints and tire tracks (example: with cardboard boxes, traffic cones, etc.) Covers loose papers and other evidence lightly (example: with plastic sheeting) to protect against drafts and water Provides security for evidence Does not move any item of evidence 11 Describe two noteworthy observations about the scene Evaluator Name: Evaluator Signature: PASS / FAIL (Circle one) Rev 02/17 CANDIDATE # Firefighter II NFPA 1001, 2013 Edition Station #: FF2 - 1 Practical Skills Test STATION: Identify and Protect Evidence of Fire Cause Protect evidence of fire cause and origin, given a flashlight and overhaul tools, so that the OBJECTIVE: evidence is properly noted and protected from further disturbance until investigators can arrive on the scene. JPR: NFPA 1001 6.3.4 Simulated fire scene with at least 3 items of evidence, including tire tracks or footprints, EQUIPMENT: and charred, loose papers. -

Firefighting in the New Economy: Changes in Skill and the Impact of Technology

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FIREFIGHTING IN THE NEW ECONOMY: CHANGES IN SKILL AND THE IMPACT OF TECHNOLOGY Brian W. Ward, Ph.D., 2010 Directed By: Dr. Bart Landry, Department of Sociology To better understand the shift in workers’ skills in the New Economy, a case study of professional firefighters ( n= 42) was conducted using semi-structured interviews to empirically examine skill change and the impact of technology. A conceptual model was designed by both introducing new ideas and integrating traditional and contemporary social theory. The first component of this model categorized firefighters’ skills according to the job-context in which they occurred, including: fire related emergencies, non-fire related emergencies, the fire station, and non-fire non-emergencies. The second component of this model drew from Braverman’s (1998/1974) skill dimension concept and was used to identify both the complexity and autonomy/control-related aspects of skill in each job-context. Finally, Autor and colleagues’ (2002) hypothesis was adapted to determine if routinized components of skill were either supplemented or complemented by new technologies. The findings indicated that skill change among firefighters was clearly present, but not uniform across job-contexts. A substantial increase in both the complexity and autonomy/control-related skill dimensions was present in the non-fire emergency context (particularly due to increased EMS-related skills). In fire emergencies, some skills diminished across both dimensions (e.g., operating the engine’s pump), yet others had a slight increase due to the introduction of new technologies. In contrast to these two contexts, the fire station and non-fire non- emergency job-contexts had less skill change. -

Vehicles for Fire Management

Project Number 48 June 1990 Vehicles for Fire Management Roscommon Equipment Center Northeast Forest Fire Supervisors In Cooperation with Michigan's Forest Fire Experiment Station Acknowledgements Participation in the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG) Fire Equipment Working Team (FEWT) Engine Study Subcommittee contributed greatly to this report. Members of that subcommittee during its Phase I - Cab & Chassis portion included: J.P. Greene (Florida) Charles Norberg (General Services Administration) Jim Stumpf(USFS) Ted Rex (BLM) Tom Uphill (USFS) Frank Winer (USFS) Brian Hutchins (Michigan) Larry Segretto (Fonnerly BLM) Bill Legan (Ventura Co. FD) Inquires, comments and suggestions regarding this project may be directed to: Fire Protection Roscommon Equipment Center U.S. Forest Service, NA c/o Forest Fire Experiment Station 5 Radnor Corporate Center, Suite 200 P.O. Box 68 100 Matsonford Road Roscommon, MI 48653 Radnor, PA 19087 Disclaimer Infonnation contained in this report has been developed for the guidance of the member states, provinces and Federal agencies. The use of trade, firm or corporation names is for the information and convenience of the user. Such use does not constitute an official evaluation, conclusion, recommendation, endorsement or approval of any product or service to the exclusion ofothers which may be suitable. Table o_f Contents Introduction 1 Definitions 1 Payload and Weight Ratings: ............................................................................................... 1 Dimensional Definitions: -

Emergency Services Wildlnd FF

Course Descriptions ESWF 1420 ESWF 2150 Emergency Services Wildland Firefighter Internship II S215 Fire Operations in the Wildland Urban 5 Interface Wildlnd FF (ESWF) * Prerequisite(s): ESWF 1410 2 * Prerequisite(s): Deparmental approval ESWF 1310 Provides students with the training and S131 Wildland Firefighter Type I experience that will assist them in gaining a job Designed to assist structure and wildland .5 in wildland fire management and suppression. firefighters who will be making tactical decisions * Prerequisite(s): Departmental approval Features participation in a 20-person wildland when confronting wildland fire that threatens fire suppression crew sponsored by the Utah life, property, and improvements in the wildland/ Meets the training needs of a Type 1 Division of Forestry, Fire and State Lands. urban interface. Includes interface awareness, Wildland Firefighter (FFT1). Presents several Also teaches about wildland fire behavior as size-up, initial strategy and incident action plan, tactical decision scenarios designed to facilitate well as fire suppression strategies and tactics. structure triage, structure protection tactics, learning the objectives and class discussion. Requires students to participate in physically incident action plan assessment and update, Introduces the student to the Fireline Handbook demanding assignments with long periods of follow up and public relations, and firefighter and provides an overview of its application. time away from home. Exposes students to safety in the interface. Meets and/or exceeds ESWF 1330 wildland fire and the various organizational NWCG standards for S-215. Look Up Look Down Look Around and mechanical tools used to manage and ESWF 2212 .5 suppress them, such as; aircraft, bulldozers, S212 Chain Saw Use in Wildland Fire * Prerequisite(s): Meet NWCG pre- large engines and other fire management and Operations qualifications or departmental approval suppression equipment. -

2015 Temporary/Seasonal Fire Positions

2015 TEMPORARY/SEASONAL FIRE POSITIONS USDA Forest Service, R-2 (Rocky Mountain Region) Black Hills National Forest The Black Hills National Forest is advertising and filling several Temporary positions for the following duty stations: Bearlodge Ranger District – Sundance, WY | Northern Hills Ranger District – Spearfish, SD Mystic Ranger District – Rapid City, SD and Hill City, SD Hell Canyon Ranger District – Custer, SD and Newcastle, WY Supervisor’s Office – Custer, SD | Boxelder Job Corps – Nemo, SD Applicants are strongly encouraged to select all duty stations to increase their chances of gaining employment on the Black Hills National Forest. If you have any questions regarding these positions please contact the individual(s) listed as the point of contact (by duty station) at the end of this document. The Black Hills National Forest has one of the largest fire programs in the Rocky Mountain region and includes: an average of 105 ignitions per year burning 10,400 acres per year (in short return interval ponderosa pine), and staffs 8 Type VI, 3 Type IV Engines, 3 Type III Engines, two 10 person IA modules, an exclusive use Type III helicopter, a National exclusive use T1 Helicopter, an Interagency Hotshot Crew, airtanker base and an interagency dispatch center. Forestry Aid (Fire) GS-0462-3 Announcement # 15-TEMP-R20462-3-FIRE-DT-JB (Announcement open 1/6/2015) You will be able to access this job in USAJOBS / www.usajobs.gov. These positions are part of a wildland fire crew, performing firefighting work on an engine or hand crew. Assignments include developing a working knowledge of fire suppression and fuels management techniques, practices and terminology. -

Fireterminology.Pdf

Abandonment: Abandonment occurs when an emergency responder begins treatment of a patient and the leaves the patient or discontinues treatment prior to arrival of an equally or higher trained responder. Abrasion: A scrape or brush of the skin usually making it reddish in color and resulting in minor capillary bleeding. Absolute Pressure: The measurement of pressure, including atmospheric pressure. Measured in pound per square inch absolute. Absorption: A defensive method of controlling a spill by applying a material that absorbs the spilled material. Accelerant: Flammable fuel (often liquid) used by some arsonists to increase size or intensity of fire. Accelerator: A device to speed the operation of the dry sprinkler valve by detecting the decrease in air pressure resulting in acceleration of water flow to sprinkler heads. Accountability: The process of emergency responders (fire, police, emergency medical, etc...) checking in as being on-scene during an incident to an incident commander or accountability officer. Through the accountability system, each person is tracked throughout the incident until released from the scene by the incident commander or accountability officer. This is becoming a standard in the emergency services arena primarily for the safety of emergency personnel. Adapter: A device that adapts or changes one type of hose thread, type or size to another. It allows for connection of hoses and pipes of incompatible diameter, thread, or gender. May contain combinations, such as a double-female reducer. Adapters between multiple hoses are called wye, Siamese, or distributor. Administrative Warrant: An order issued by a magistrate that grants authority for fire personnel to enter private property for the purpose of conducting a fire prevention inspection or similar purpose. -

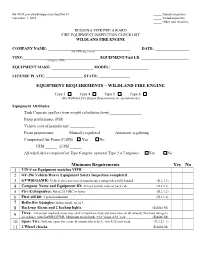

WILDLAND FIRE ENGINE Minimum Requirements Yes No 9

R6 VIPR pre-award inspection checklist v1 _____ Passed inspection December 1, 2015 _____ Failed inspection _____ Other (see remarks) REGION 6 VIPR PRE-AWARD FIRE EQUIPMENT INSPECTION CHECKLIST WILDLAND FIRE ENGINE COMPANY NAME: __________________________________________ DATE: (On VIPR Agreement) VIN#:_______________________________________ EQUIPMENT/Unit I.D. (Complete VIN) EQUIPMENT MAKE: _____________________ MODEL: ___________________ LICENSE PLATE: STATE: EQUIPMENT REQUIREMENTS – WILDLAND FIRE ENGINE Type 3 Type 4 Type 5 Type 6 (See Wildland Fire Engine Requirements for specifications) Equipment Attributes: Tank Capacity (gallons from weight calculation form) Pump performance (PSI) Vehicle year of manufacture Foam proportioner ____ Manually regulated ____ Automatic regulating Compressed Air Foam (CAFS) Yes No CFM ______ @ PSI ______ All wheel drive (required on Type 6 engine, optional Type 3,4,5 engines) Yes No Minimum Requirements Yes No 1 VIN # on Equipment matches VIPR 2 OF-296 Vehicle/Heavy Equipment Safety Inspection completed 3 GVWR/GAWR: Vehicle does not exceed manufactures rating when fully loaded (D.2.1.2) 4 Company Name and Equipment ID: Affixed to both sides of truck cab (D.2.2.3) 5 Fire Extinguisher, Rated 2A 10BC or better (D.2.1.2) 6 First aid kit: 5 person minimum (D.2.1.2) 7 Reflective triangles: bidirectional, set of 3 8 Back-up Alarm and 2 backup lights (Exhibit M) Tires: All season mud and snow tires (4x4’s must have mud and snow tires on all wheels) Tire load ratings in 9 accordance with GAWR/GVWR. Minimum tread depth: 4/32” front, 2/32” rear (Exhibit M) 10 Spare Tire: Full size spare tire securely mounted to vehicle, min 4/32 inch tread (D.2.2.1.1) 11 2 Wheel chocks (Exhibit M) R6 VIPR pre-award inspection checklist v1 December 1, 2015 Minimum Requirements – continued Yes No 12 Water Tank: Firmly attached to frame or structurally sound flatbed (D.2.1.2) Tank baffling: Must have longitudinal and transverse baffles; distance between vertical tank walls and baffles or between parallel baffles shall not exceed 52”. -

NKCTC Firefighter Fundamentals Manual

NKCTC Firefighter Fundamentals SEPTEMBER 2020 North King County Training Consortium TABLE OF CONTENTS (Click on any title to jump to that SECTION) SECTION SECTION TITLE 1 Hand Tools 2 Rope 3 Power Equipment 4 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) 5 Self-Contained Breathing Apparatus (SCBA) 6 Forcible Entry 7 Search & Rescue 8 Firefighter Survivability 9 Ladders 10 Ventilation 11 Hose & Appliances Click the button to return to this page HAND TOOLS Alan wrench set/Hex key/ Allen key: because the flat head can be used as a striking tool. Long arching swings should not be used with axes. This method increases the danger of hitting other members or overhead obstructions. When using a A tool with a hexagonal cross-section used wooden handled axe, due to the grain of to drive bolts and screws that have a the wood, the strongest axis when using the hexagonal socket in the head (internal axe to pry is in line with the head or pick of wrenching hexagon drive). They may be the axe. Care must be used when prying in either American or Metric sizes. the direction of either side of the head of the axe. AXES Pry Axe: Pick Head Axe: The pry axe has features not normally found Comes with a 28-36” handle with a 6-8 lb. on traditional rescue tools. The head of the axe head on one side and a pick head on tool has a shortened pick head axe with the other. This is an excellent prying tool serrated teeth on the underside of the axe when the pick end is engaged.