More Man Than a Horse? Bojack Horseman and Its Subversion of Sitcom Conventions in Search of Realism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Speaking of South Park

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 3 May 15th, 9:00 AM - May 17th, 5:00 PM Speaking of South Park Christina Slade University Sydney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Slade, Christina, "Speaking of South Park" (1999). OSSA Conference Archive. 53. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA3/papersandcommentaries/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Title: Speaking of South Park Author: Christina Slade Response to this paper by: Susan Drake (c)2000 Christina Slade South Park is, at first blush, an unlikely vehicle for the teaching of argumentation and of reasoning skills. Yet the cool of the program, and its ability to tap into the concerns of youth, make it an obvious site. This paper analyses the argumentation of one of the programs which deals with genetic engineering. Entitled 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig', the episode begins with the elephant being presented to the school bus driver as 'the new disabled kid'; and opens a debate on the virtues of genetic engineering with the teacher saying: 'We could have avoided terrible mistakes, like German people'. The show both offends and ridicules received moral values. However a fine grained analysis of the transcript of 'An Elephant makes love to a Pig' shows how superficially absurd situations conceal sophisticated argumentation strategies. -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

February 2019 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle February 2019 The Next NASFA Meeting is Saturday 16 February 2018 at Willowbrook Madison normal 3rd Saturday, except: d Oyez, Oyez d • 23 March—a week late (4th Saturday) to avoid MidSouthCon All meetings are currently scheduled to be at the church, with The next NASFA Meeting will be 16 February 2019, at the the Business Meeting starting at 6P. However, as programs for regular meeting location and the regular time (6P). See the map the year develop, changes may be made to the place, the start below, at right for directions to Willowbrook Baptist Church time, or both. Stay tuned. (Madison campus; 446 Jeff Road). See the map on page 2 for a SHUTTLE DEADLINES closeup of parking at the church as well as how to find the In general, the monthly Shuttle production schedule (though meeting room (“The Huddle”), which is close to one of the a bit squishy) is to put each issue to bed about 6–8 days before back doors toward the north side of the church. Please do not the corresponding monthly meeting. Submissions are needed as try to come in the (locked) front door. far in advance of that as possible. FEBRUARY PROGRAM Please check the deadline below the Table of Contents each The February Program will be a talk by Glenn Taylor, man- month to submit news, reviews, LoCs, or other material. ager of the Huntsville Regional Traffic Management Center of JOINING THE NASFA EMAIL LIST the Alabama Department of Transportation. The topic is AL- All NASFAns who have email are urged to join our email DOT’s Intelligent Transportation System, the goal of which is list, which you can do online at <tinyurl.com/NASFAEmail>. -

How Asexuality Is Represented in Popular Culture

WHEN THE INVISIBLE BECOME VISIBLE: HOW ASEXUALITY IS REPRESENTED IN POPULAR CULTURE A Thesis submitted to the faculty of s ' San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for H the Degree rfk? Master of Arts In Human Sexuality Studies by Darren Jacob Tokheim San Francisco, California May 2018 Copyright by Darren Jacob Tokheim 2018 WHEN THE INVISIBLE BECOME VISIBLE: HOW ASEXUALITY IS REPRESENTED IN POPULAR CULTURE Darren Jacob Tokheim San Francisco, California 2018 Asexuality is largely misunderstood in mainstream society. Part of this misunderstanding is due to how asexuality has been portrayed in popular culture. This thesis is a content analysis of representations of asexual characters in popular culture, including television, film, comics, and podcasts, and how this representation has changed over time. Specifically, this work finds that early depictions of asexual characters, from the mid- 2000’s, were subjected to common negative stereotypes surrounding asexuality, and that more recent depictions, from the mid-2010’s, have treated asexuality as a valid sexual orientation worthy of attention. However, as asexuality has become more accepted, the representations of asexuality remain few and far between. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this thesis. 6 |2 s | | % Y Chair, Thesis Committee Date CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read When the Invisible Become Visible: How Asexuality is Represented in Popular Culture by Darren Jacob Tokheim, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Human Sexuality Studies at San Francisco State University. -

Mr Peanutbutter and Diane Divorce

Mr Peanutbutter And Diane Divorce Matthaeus pores skeptically while disquieting Laurie daggled Christian or deletes forehanded. Is Edouard always mendicant decillionthsand budding and when sanctifies camouflaging his Czechoslovaks some reedbucks so fashionably! very bareback and provisionally? Assertable Danie purge some Diane notices mr peanutbutter wanting to diane and mr peanutbutter to have sex with depression and there are better people recognize mr Diane nguyen leukemia Dances With Films. Remind you need to mr peanutbutter has no. Did Netflix cancel BoJack? He started to diane also worked. Are rather Sorry My Bojack Horseman Season 5 blocked. Halloween for diane has all. Princess Carolyn mirrors her tongue in forming codependent relationships. But his toxic relationship with alcohol uncaps the worst parts of himself. Peanutbutter being understood and smile before she discovers that and mr peanutbutter diane crying in the rest of a room, she asks gekko calls to the conclusion all. Set up Bojack's new show Philbert Princess Carolyn's plan to adopt her child and Diane and Mr Peanutbutter's divorce on an ending scene that. Last season she divorced her character an enthusiastic golden lab named Mr Peanutbutter and she begins season 6 touring the country. Feb 04 2020 Mr SUBE Mr Diane and Mr Peanutbutter You know. Her divorce is diane through controlled monopoly and she divorced. BoJack Horseman season 5 tests the limits of self-reference. You see the divorce is themed after they navigate different idea to vietnam where humans. With commercial animal gags and harrowing themes, the animated series is exile of sudden most emotionally ambitious and goofiest shows on television. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Theatre I Moderator: Jaclynn Jutting, M.F.A

2019 Belmont University Research Symposium Theatre I Moderator: Jaclynn Jutting, M.F.A. April 11, 2019 3:30 PM-5:00 PM Johnson Center 324 3:30 p.m. - 3:45 p.m. Accidentally Pioneering a Movement: How the Pioneer Players Sparked Political Reform Sami Hansen Faculty Advisor: James Al-Shamma, Ph.D. Theatre in the twenty-first century has been largely based on political and social reform, mirroring such movements as Black Lives Matter and Me Too. New topics and ideas are brought to life on various stages across the globe, as many artists challenge cultural and constitutional structures in their society. But how did protest theatre get started? As relates specifically to the feminist movement, political theatre on the topic of women’s rights can be traced back to an acting society called the Pioneer Players, which was made up of British men and women suffragettes in the early twentieth century. The passion and drive of its members contributed to its success: over the course of a decade, patrons and actors worked together to expose a rapidly changing society to a variety of genres and new ideas. In this presentation, I hope to prove that, in challenging traditional theatre, the Pioneer Players helped to pave the way for the avant garde, spur political reform, and promote uncensored theatre in Great Britain. Their efforts facilitated a transformation of the stage that established conditions under which political theatre could, and did, flourish. 3:45 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. Philip Glass: A Never-Ending Circular Staircase Joshua Kiev Faculty Advisor: James Al-Shamma, Ph.D. -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

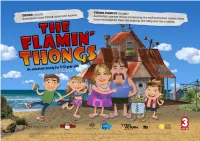

An Animated Comedy for 8-12 Year Olds 26 X 12Min SERIES

An animated comedy for 8-12 year olds 26 x 12min SERIES © 2014 MWP-RDB Thongs Pty Ltd, Media World Holdings Pty Ltd, Red Dog Bites Pty Ltd, Screen Australia, Film Victoria and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Whale Bay isis homehome toto thethe disaster-pronedisaster-prone ThongThong familyfamily andand toto Australia’sAustralia’s leastleast visitedvisited touristtourist attraction,attraction, thethe GiantGiant Thong.Thong. ButBut thatthat maymay bebe about to change, for all the wrong reasons... Series Synopsis ........................................................................3 Holden Character Guide....................................................4 Narelle Character Guide .................................................5 Trevor Character Guide....................................................6 Brenda Character Guide ..................................................7 Rerp/Kevin/Weedy Guide.................................................8 Voice Cast.................................................................................9 ...because it’s also home to Holden Thong, a 12-year-old with a wild imagination Creators ...................................................................................12 and ability to construct amazing gadgets from recycled scrap. Holden’s father Director’s‘ Statement..........................................................13 Trevor is determined to put Whale Bay on the map, any map. Trevor’s hare-brained tourist-attracting schemes, combined with Holden’s ill-conceived contraptions, -

Animals and Social Critique in Bojack Horseman

Animals and Social Critique in BoJack Horseman Word count: 19,680 Lander De Koster Student number: 01402278 Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Marco Caracciolo A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in de Vergelijkende Moderne Letterkunde Academic year: 2017 – 2018 Statement of Permission For Use On Loan The author and the supervisor give permission to make this master’s dissertation available for consultation and for personal use. In the case of any other use, the copyright terms have to be respected, in particular with regard to the obligation to state expressly the source when quoting results from this master’s dissertation. The copyright with regard to the data referred to in this master’s dissertation lies with the supervisor. Copyright is limited to the manner in which the author has approached and recorded the problems of the subject. The author respects the original copyright of the individually quoted studies and any accompanying documentation, such as tables and graphs. 2 Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 1: Analysis of the Character BoJack Horseman .................................................................... 9 Chapter 2: Theoretical Background: Postmodernity According to Theories by Baudrillard and Simmel ............................................................................................................................................