Jason Epstein at the 2008 Hong Kong Book Fair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Success of the UAE Publishing Market Around the World

Success of the UAE Publishing Market around the World Over the past four decades, the UAE publishing industry has grown from a fledgling industry into a regional trade hub Timeline UAE gains independence; only 48% of the adult population is literate; 1971 38% literacy among females 1979 Number of books published in the UAE reaches 6 1980 Press and Publications Law introduced 1982 Sharjah International Book Fair held for the first time 1984 UAE Writers Union established 1992 Law on the Protection of Intellectual Works and Copyright introduced 1996 Signatory to the WTO TRIPS Agreement Signatory to the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the Berne Convention for the 2004 Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 2007 Abu Dhabi International Book Fair held for the first time in its new format 2009 Emirates Publishers Association (EPA) is established Emirates Intellectual Property Association and the UAE Board on Books 2010 for Young People established 2012 EPA becomes a full member of the International Publishers Association 2014 Book exports exceed $40 Million Literacy rate reaches 94% with literacy among females exceeding that of 2015 males by 2% Kalimat becomes first Emirati publishing house to win Bologna Children’s 2016 Book Fair Award Sharjah nominated as 2019 World Book Capital 2018 3 Sources: UNESCO Archives, Staff Analysis The Emirates Publishers Association is a national organization that was created to support capacity development of the UAE publishing industry EPA is a leading voice for change … … with 10 key priorities that guide its work . The Emirates Publishers Association (EPA) was established in 2009 1 Aligning key stakeholders to increase collaboration among publishing industry stakeholders to 2 Expanding markets address various industry challenges 3 Improving copyright and legal framework . -

Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf Publisher of Borzoi Books Fall 2009 22112_K-Fa09_f_MM.qxp:K-Fa09_1p_r1 3/6/09 3:21 PM Page 43 Alfred A.Knopf Index of Titles Page Page The American Civil War, John Keegan 85 Lincoln, Life-Size, Philip B. Kunhardt III, American Icon, Teri Thompson, Peter W. Kunhardt, and Peter W. Nathaniel Vinton, Michael O’Keeffe, and Kunhardt, Jr. 89 Christian Red 46 The Museum of Innocence, Orhan Pamuk 83 Angel Time, Anne Rice 79 The National Parks, Dayton Duncan and The Art Student’s War, Brad Leithauser 94 Ken Burns 55 The Bauhaus Group, Nicholas Fox Weber 78 News of the World, Philip Levine 74 Blood’s A Rover, James Ellroy 63 Noah’s Compass, Anne Tyler 61 The Case for God, Karen Armstrong 57 Nocturnes, Kazuo Ishiguro 53 The Children’s Book, A. S. Byatt 69 Nothing Was the Same, Kay Redfield Civil War Wives, Carol Berkin 64 Jamison 65 The Complete Lyrics of Johnny Mercer, On Thin Ice, Richard Ellis* 92 Johnny Mercer 80 The Original of Laura, Vladimir Nabokov 97 Conquering Fear, Harold S. Kushner 81 Painting Below Zero, James Rosenquist 86 Conversations with Woody Allen, Eric Lax 52 A Phone Call to the Future, Mary Jo Crossers, Philip Caputo 76 Salter 54 Crude World, Peter Maass 58 The Pleasures of Cooking for One, The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Judith Jones 62 Stories, Leo Tolstoy 98 The Queen Mother, William Shawcross 93 Defend the Realm, Christopher Andrew 77 Redeeming Features, Nicholas Haslam 96 Easy, Marie Ponsot 84 Robert Altman, Mitchell Zuckoff 73 Eating, Jason Epstein 82 Robert Redford, Michael Feeney Callan 95 The Education of a British-Protected Child, Chinua Achebe* 72 Selected Poems, Frank O’Hara 54 Endpoint and Other Poems, John Updike 45 The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior, David Allen Sibley 48 A Gate at the Stairs, Lorrie Moore 59 The Slippery Year, Melanie Gideon 51 The Godfather of Kathmandu, John Burdett 75 Sweet Thunder, Wil Haygood* 68 Half the Sky, Nicholas D. -

African Publisher Networks

AFRICANPUBLISHING REVIEW A Newsletter of the African Publishers Network • ISSN: 2665-0959 • VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 1 • FEB 2019 INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION IN THIS ISSUE TO ORGANIZE THE SECOND EDITION OF International Publishers Association REGIONAL SEMINAR IN NAIROBI to organize the second edition of Re- 01 he second edition of Interna- Kenyan Publishers Association, gional Seminar in Nairobi tional Publishers Associa- the host, is the umbrella body T APNET offers publishing training to tion (IPA) Seminar is being held for book publishers in Kenya. two Burundian delegates 02 on 14th and 15th June, 2019 at The Association is the largest the Movenpick Hotel and Res- publishers association in East- The Turkish Press & Publishers Copy- right & Licensing Society (TBYM) to idences, Nairobi, Kenya. The ern Africa. Its contributions 05 Seminar is themed: “Africa Ris- organize the 4th Istanbul Fellowship including capacity building, Programme ing: Realising Africa’s Potential advocacy, restructuring of pub- as a Global Publishing Leader lishing, trade promotion have APNET participates in the 28th Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, 2018 06 in the 21st Century.” The host of advanced the Kenyan book in- the Seminar is Kenyan Publish- dustry and it is also the leader Tunis International Book Fair invites ers Association (KPA). in Eastern Africa. Kenya is one APNET for collective exhibition 07 of the few countries in Africa This upcoming seminar will 2019 World International Book Fair that has attained 1:1 book ratio Calendar 08 bring together presidents of Af- of educational books to pupils/ rican publishers’ associations, students. This Nairobi Seminar APNET participates in the 70th Frank- 11 executives of IPA and some vet- is building on the first seminar furt Book Fair eran African and foreign book to increase success in the pub- APNET signs an MoU with Turkish industry players to discuss issues lishing landscape of Africa. -

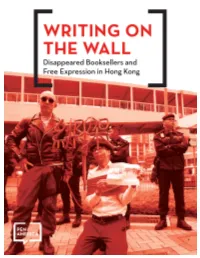

Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1

Writing on the Wall: Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong 1 WRITING ON THE WALL Disappeared Booksellers and Free Expression in Hong Kong November 5, 2016 © 2016 PEN America. All rights reserved. PEN America stands at the intersection of literature and human rights to protect open expression in the United States and worldwide. We champion the freedom to write, recognizing the power of the word to transform the world. Our mission is to unite writers and their allies to celebrate creative expression and defend the liberties that make it possible. Founded in 1922, PEN America is the largest of more than 100 centers of PEN International. Our strength is in our membership—a nationwide community of more than 4,000 novelists, journalists, poets, essayists, playwrights, editors, publishers, translators, agents, and other writing professionals. For more information, visit pen.org. Cover photograph: Artist Kacey Wong protests the Causeway Bay Books disappearances bound and gagged, sporting a red noose bearing the Chinese characters for "abduction." The sign in his hand says "Hostage is well. " Photo courtesy of Kacey Wong. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 “One Country, Two Systems” Under Threat ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Hong Kong’s Legal Framework -

In Search of Books in Hong Kong and Taipei

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 9 2-1-2003 In Search of Books in Hong Kong and Taipei Wen-ling Liu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Liu, Wen-ling (2003) "In Search of Books in Hong Kong and Taipei," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. SEARCH BOOKS HONG KONG TAIPEI wenlingwen ling liu indiana university newly appointed librarian east asian studies I1 eager leableamlearn book trade publishing trends east asia hong kong book fair july 2002 offered me good chance broadening my knowledge led frank xu brooklyn public library sixteen librarians united states participated event opportunity partially owed hong kong book fairus librarian invitation program jointly sponsored american library association hong kong book fair I1 very glad three CEAL members traveling me karen wei university illinois urbana champagne ping situ university arizona library annie lin university california davis annie I1 planned make best use trip moment heard both us team inspired tips our colleagues contacted libraries chinese university hong kong hong kong university both gifts -

2008 ೠҵޙߣਗࢎসোх Lti Korea Annual Report 2008

ISSN 1976-9997 2008 ೠҴޙߣਗࢎসোх LTI KOREA ANNUAL REPORT 2008 ӝദౠ ӝࠄߑೱীࢲ ಝࠄ ֙ ࢎসѾ 2008 Annual Report : Three Main Directions ೱز ನழझ ]Ҵղ ӂ ೧৻ࣻ оٜsಕझ౭ߥ അܰನ ]rࢲ Ԙ ޛ ޙӂী ೠҴۉࣁ҅৬ ೣԋ ] ই Sharing Korean Literature With The World Korea Literature Translation Institute ޙೠҴ חࣁ҅৬ ೣԋೞ ݾର Contents 04 06 दझమ ҳ୷u 02 A Message from Dr. Joo Youn Kim, the New Director of LTI Korea ܨਬӝ Ү חߊрࢎ ]tࣁ҅৬ ҕਬೞ 14 ӝࠄߑೱীࢲ ಝࠄ ֙ ࢎসѾ 04 2008 Annual Report : Three Main Directions [ ӝദౠ ೱ 08 Domestic Copyright Exports Trendز ನழझ ]Ҵղ ӂ ೧৻ࣻ Ԙ 12 Spreading Korean Literature to the Arabic World, a Jump Startޛ ޙӂী ೠҴۉࣁ҅৬ ೣԋ ]ই оٜs 16 2008 Seoul Young Writers' Festival അܰನ ]rࢲ 16 ೠҴޙߣਗ ࣗѐ 20 Introduction to LTI Korea ࢎস ࣗѐ ] ߣ߂౸ਗ 24 Translation & Publication Grants ֙ International Exchange Programs 46 ܨ ೧৻Үޙࢎস ࣗѐ ]ೠҴ ֙ 48 ਭࢿࢎস 66 Fostering Professional Translators ۱ੋޙࢎস ࣗѐ ] ֙ ഘࠁ 78 Promoting Korean Literatureޙࢎস ࣗѐ ]ೠҴ ֙ नр উղ 82 New Books 2008 72 Director’s Column | ߊрࢎ 02 חtࣁ҅৬ ҕਬೞ ਬӝ Үܨ दझమ ҳ୷u ೠҴޙߣਗࢎসোх 2008 ߊрࢎ פߣਗ ӣোੑޙө ೠҴפউ֞ೞभ פߣਗ ֙ ೠ ೧ ࣁ҅৬ ഐ൚ೞӝ ਤೠ ৈ۞ о ࢎসਸ ӝദೞҊ पୌী ҂णޙೠҴ פਸ ղ ֬णߣਗ ࢎসোхޙ֙ ೠҴ ઁ Ӓ Ѿपਸ ೠ ӂ ଼ী ݽই ই ߣਗ ߧ റޙೠҴפࢿҗٜ ঋण ܘ݅ ӘԈ ૣ ח ೧৻Үࢼ ࢎޙܻ ࣁ҅౸द ۽ઁ ࠄѺਵ ࣗѐରਗ ߣ౸ࢎসীࢲ द೧ޙୡӝ ೠҴ بۄࠁ؊ ݅ ചࣿ బஎ ߣਸ ਤೠrӝޙ חܖ೧ ӝୡܳ ޙ ਸ ೱೠr౸ӂ ࣻഝࢿച ࢎসs ߣޙ؊ աইо ೠҴ ಕझ౭ߥ ѐ୭ޙ ߂ Ҵઁ ܨࣁ҅ оٜҗ Ү ୡࣿߣਗࢎসs ࢎস নҗ ী য Ӓ և৬ Өо ؊೧оҊ ١ ۔Ӓ۽झ ؍о নࢿ ߂ ӝߣоٜ ۨ פण ۽ӒܻҊ ߄פ അप ࣁ҅о ೞաਸ ࠁ ؊ ӓݺೞѱ ࠁৈҊ णטয় חә߸ೞҊ ೠ ೧ Ѧ ӝ ೧ੑ ী۽ࢲפӘ ࢚ഐ ࣗాҗ ೧ ਃࢿ ؊ ழҊ ण ۧ٠פয ࣻ হणܖ ۽ઁ חೞ ঋҊࢲా ܳܨఋੋҗ Ү חೞ݅ ӝ ೧פ פѪ ਗജ ࢿѺਸ ыण חചܳ ܲ ٜҗ ҕਬೠޙ ߂ޙܻ ই ۽ ߊਵ۽ োх ࢎসٜਸ द ೠߣ ԝԝ ಝ ࢜ޘ դ ೠ ೧ ࢿҗܳ ח൞ ਬӝ חࣁ҅৬ ҕਬೞ ਸ ֫Ҋ ཫฯ ߥ ҃੬۱ ъചܳ ా೧ ҴѺ۽ࢲ Ӗب ߂ޙೠҴ بೠ ೧ ৢ ೧৻ࣗѐ ঌ য়ݫоੋrࣻೠ ߣоsܳ নࢿೞҊ ޙೠҴ दझమਸ ҳ୷ೞݴ ܨ Ү פؘ ֢۱ೞѷणחਗೞ פҊणפ౸ࢎ ৈ۞࠙ ࢿਗҗ ҙबਸ ࠗఌ٘݀ ߣо ੋ оޙೠҴ ਘ ֙ ೠҴޙߣਗ ӣো 03 A Message from Dr. -

International Leads

ISSN 0892-4546 International Leads A Publication of the International Relations Round Table of the American Library Association Volume 17 March 2003 Number 1 The Central University Library Rises from the Ashes in Bucharest, Romania By James P. Niessen he dominant image for Romanian librarians of the events for this purpose already in 1931. As the result of this work, Tof 1989 is of the smoking ruin of the Central the library’s total internal space and reading room area more University Library (BCU), caught in the crossfire on than tripled; the stacks space more than quadrupled and can what is today officially Revolution Square. The fire now accommodate two million volumes, and there are 150 consumed 500,000 volumes, including the Department of public computers where there were none previously. Rare Books and Manuscripts with the papers of many leading writers, most traumatically those of Mihai The restoration of the building Eminescu, and various incunabula and other early imprints. Library Director Ion Stoica rededicated the library in the presence of the country’s political leaders and The old building distinguished foreign guests on November 20, 2001, The ruined building had been dedicated in 1914. It gained a 110 years after its founding. He recounted with justifiable central role in the life of the country’s leading university, as a pride the earlier history and recent reconstruction of the host for distinguished public lectures. After 1948, it was library and spoke eloquently of its future. The new library regarded as a national center for Romanian literary was more than “a large documentary entity. -

July 2020 Newsletter

ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY NEWSLETTER HONG KONG July 2020 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: + (852) 5435 5754 GPO Box 3864, Hong Kong www.royalasiaticsociety.org.hk http://www.facebook.com/RoyalAsiaticSocietyHongKong Twitter: RASHK 1959 Michel Maruca presents the history of Hong Kong’s Botanical and Zoological Gardens to RASHK Members- June 2020 Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong | 2020 Contents MESSAGE FROM YOUR PRESIDENT 3 FUTURE ACTIVITIES Sun, 5th July 2020 Local Visit Blue Lotus Gallery – Back to Nature Exhibition 4 Fri, 10th July 2020 Online Lecture Three Asian Divas: Women, Art and Culture in Shiraz, Delhi 6 and Yangzhou Fri, 24th July 2020 Online Lecture Trading Places: 12 Years and 2,784,010 Steps Later! 8 Sat, 15th Aug 2020 Online Lecture A Stormy Petrel: The Life and Times of John Pope Hennessy 10 Sat, 5th Sept 2020 Local Visit (Revisit) Julie and Jesse / Latitude 22N Ceramics Studio 11 RECENT ACTIVITIES Sat, 9th May 2020 China’s Russian Princess: The Silent Wife of Chiang Ching-kuo 13 Sat, 23rd May 2020 The Last Journey of the San Bao Eunuch, Admiral Zheng He 14 Sat, 29th May 2020 Heaven, Earth and Man in Harmony: Chinese Art Appreciation 14 and Spirituality Fri, 5th June 2020 Murders of Old China 15 Sat, 20th June 2020 History of the Hong Kong Botanical and Zoological Gardens – 15 Guided Walk The Sir Lindsay and Lady Ride Memorial Fund The Ride Fund testimonial Stephen Davies 17 Letter from the RASHK President Helen Tinsley 18 OF GENERAL INTEREST Hong Kong Book Fair 19 Book presentation - Painter and Patron: Illustrations of the Maritime Silk Road in 16th century Códice 19 Casanatense by Peter Gordon & Juan José Morales Book Presentation - Journeys with a Mission (2018) and Over the Years (2017) by Dr. -

Hab123 Controlling Officer’S Reply

Examination of Estimates of Expenditure 2020-21 Reply Serial No. HAB123 CONTROLLING OFFICER’S REPLY (Question Serial No. 2259) Head: (95) Leisure and Cultural Services Department Subhead (No. & title): (-) Not Specified Programme: (5) Public Libraries Controlling Officer: Director of Leisure and Cultural Services (Vincent LIU) Director of Bureau: Secretary for Home Affairs Question: With regard to the public library services of the Leisure and Cultural Services Department (LCSD), please inform this Committee of the following: (a) What were the respective numbers of loans of Chinese and English books from public libraries in the past year? What were the respective numbers of loans of locally published Chinese and English books? (b) What was the total expenditure on the acquisition of books by public libraries in the past year? What were the respective expenditures on the acquisition of locally published Chinese and English books? What are the estimated expenditures on the acquisition of locally published Chinese and English books and the total expenditure on book acquisition for the coming year? (c) For the English books for adults/English books for children/Chinese books for adults/Chinese books for children which are available for loan, please list under the categories in the table below titles of the top 10 books in terms of copies acquired in the past financial year. What was the number of books acquired and the expenditure incurred, as well as the number of loans for the books in the financial year? (Note: please exclude the publications -

Complete 8.2.Qxd

NOTESVolume 8, Number 2, March 2001 E THE NEW YORK SOCIETY LIBRARY BOOK AWARDS, 2000 D The New York Society Library Book Awards were established in 1996 to honor current authors who capture the essence of New York City. This year’s jury comprises Constance Rogers Roosevelt, Chair; Richard B. Bernstein, Barbara Cohen, Joan K. Davidson, Hope Cooke, Christopher Gray, Tom Mellins, Roger Pasquier, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Jean Strouse, and Wendy Wasserstein. The 2000 Book Awards will be presented Wednesday, May 2 at 5:30 P.M. in the Members’ Room. The presenters will be Wendy Wasserstein, Eric Foner, Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Christopher Gray, and Tony Hiss. Library members are cordially invited to the award ceremony and reception, but space is limited. Reservations must be placed with the Events Office (212-717-0357) by April 26. E AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT D E AWARD FOR FICTION D Vincent Seyfried, The Amazing Adventures Historian Seyfried’s monu- of Kavalier and Clay Weber-Ziel mental work Michael Chabon focuses on Queens before it (Random House) became part of greater New “The depth of Chabon's thought, his York and on the history of sharp language, his inventiveness and the Long Island Rail Road. his ambition make this a novel of Christopher Gray calls him towering achievement.” “the grand old man of -The New York Times Book Review From Seyfried’s Queens: A Pictorial E AWARD FOR HISTORY D E AWARD FOR NATURAL HISTORY D Working-Class New York: Heartbeats in the Muck: The Life and Labor Since History, Sea Life, and World War II Environment Joshua B. -

Contributors

Contributors Mashey Bernstein holds a PhD in American Literature from the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he currently teaches in the Writing Program and in the Film and Media Studies Department. He has written extensively on Mailer in The Mailer Review, Studies in American-Jewish Literature, the San Francisco Review of Books, and the London Jewish Chronicle. He also writes on film, especially Jewish aspects of the media. Scott Duguid is in the process of completing his Doctoral Thesis on Norman Mailer and the aesthetics/politics of the avant-garde at the University of Edinburgh. His interests include twentieth-century fic- tion, with a particular focus on America; intersections between liter- ature and art history; theories of modernism and postmodernism. He has published articles on Norman Mailer, and on Warhol’s films. Jason Epstein was Editorial Director at Random House for forty years, where he developed the Vintage paperbacks series and pub- lished Norman Mailer, Vladimir Nabokov, E.L. Doctorow, Gore Vidal, Philip Roth, Elaine Pagels, and Richard Holbrook. In 1952 he created the Anchor Books imprint; in 1963 he cofounded the New York Review of Books, and in 1979 he became one of the cofounders of the Library of America, which was intended to market archival quality editions of American classic literature. The first volumes were published in 1982, and the company now prints about 250,000 vol- umes per year. Epstein is the first winner of the National Book Award for Distinguished Service to American Letters (1988) and, in 2007, he has won the Philolexian Award for Distinguished Literary Achievement.