Subcontinental Nuclear Instability: the Spiralling Nightmare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown Introduction During the summer of 1781, British general Lord Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, Virginia, the seat of York County and Williamsburg’s closest port. Cornwallis’s commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, ordered him to establish a naval base for resupplying his troops, just after a hard campaign through South and North Carolina. Yorktown seemed the perfect choice, as at that point, the river narrowed and was overlooked by high bluffs from which British cannons could control the river. Cornwallis stationed British soldiers at Gloucester Point, directly opposite Yorktown. A British fleet of more than fifty vessels was moored along the York River shore. However, in the first week of September, a French fleet cut off British access to the Chesapeake Bay, and the mouth of the York River. When American and French troops under the overall command of General George Washington arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis pulled his soldiers out of the outermost defensive works surrounding the town, hoping to consolidate his forces. The American and French troops took possession of the outer works, and laid siege to the town. Cornwallis’s army was trapped—unless General Clinton could send a fleet to “punch through” the defenses of the French fleet and resupply Yorktown’s garrison. Legend has it that Cornwallis took refuge in a cave under the bluffs by the river as he sent urgent dispatches to New York. Though Clinton, in New York, promised to send aid, he delayed too long. During the siege, the French and Americans bombarded Yorktown, flattening virtually every building and several ships on the river. -

India's Military Strategy Its Crafting and Implementation

BROCHURE ONLINE COURSE INDIA'S MILITARY STRATEGY ITS CRAFTING AND IMPLEMENTATION BROCHURE THE COUNCIL FOR STRATEGIC AND DEFENSE RESEARCH (CSDR) IS OFFERING A THREE WEEK COURSE ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. AIMED AT STUDENTS, ANALYSTS AND RESEARCHERS, THIS UNIQUE COURSE IS DESIGNED AND DELIVERED BY HIGHLY-REGARDED FORMER MEMBERS OF THE INDIAN ARMED FORCES, FORMER BUREAUCRATS, AND EMINENT ACADEMICS. THE AIM OF THIS COURSE IS TO HELP PARTICIPANTS CRITICALLY UNDERSTAND INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY INFORMED BY HISTORY, EXAMPLES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE. LED BY PEOPLE WHO HAVE ‘BEEN THERE AND DONE THAT’, THE COURSE DECONSTRUCTS AND CLARIFIES THE MECHANISMS WHICH GIVE EFFECT TO THE COUNTRY’S MILITARY STRATEGY. BY DEMYSTIFYING INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY AND WHAT FACTORS INFLUENCE IT, THE COURSE CONNECTS THE CRAFTING OF THIS STRATEGY TO THE LOGIC BEHIND ITS CRAFTING. WHY THIS COURSE? Learn about - GENERAL AND SPECIFIC IDEAS THAT HAVE SHAPED INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY ACROSS DECADES. - INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORKS AND PROCESSES. - KEY DRIVERS AND COMPULSIONS BEHIND INDIA’S STRATEGIC THINKING. Identify - KEY ACTORS AND INSTITUTIONS INVOLVED IN DESIGNING MILITARY STRATEGY - THEIR ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES. - CAUSAL RELATIONSHIPS AMONG A MULTITUDE OF VARIABLES THAT IMPACT INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. Understand - THE REASONING APPLIED DURING MILITARY DECISION MAKING IN INDIA - WHERE THEORY MEETS PRACTICE. - FUNDAMENTALS OF MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND ESCALATION/DE- ESCALATION DYNAMICS. - ROLE OF DOMESTIC POLITICS IN AND EXTERNAL INFLUENCES ON INDIA’S MILITARY STRATEGY. - THREAT PERCEPTION WITHIN THE DEFENSE ESTABLISHMENT AND ITS MILITARY ARMS. Explain - INDIA’S MILITARY ORGANIZATION AND ITS CONSTITUENT PARTS. - INDIA’S MILITARY OPTIONS AND CONTINGENCIES FOR THE REGION AND BEYOND. - INDIA’S STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS AND OUTREACH. -

The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 8-22-2013 Book Review of The eV rdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War Robert Sloane Boston Univeristy School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Robert Sloane, Book Review of The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War, No. 13-29 Boston University School of Law, Public Law Research Paper (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/24 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REVIEW OF JAMES Q. WHITMAN, THE VERDICT OF BATTLE: THE LAW OF VICTORY AND THE MAKING OF MODERN WAR (2012) Boston University School of Law Worrking Paper No. 13-39 (August 22, 2013) Robert D. Sloane Boston University Schoool of Law This paper can be downloaded without charge at: http://www.bu.edu/law/faculty/scholarship/workingpapers/2013.html The Verdict of Battle: The Law of Victory and the Making of Modern War. By James Q. Whitman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012. Pp. vii, 323. Index. For evident reasons, scholarship on the law of war has been a growth industry for the past two decades. -

A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations from 1941 to the Present

CRM D0006297.A2/ Final July 2002 Charting the Pathway to OMFTS: A Historical Assessment of Amphibious Operations From 1941 to the Present Carter A. Malkasian 4825 Mark Center Drive • Alexandria, Virginia 22311-1850 Approved for distribution: July 2002 c.. Expedit'onaryyystems & Support Team Integrated Systems and Operations Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N0014-00-D-0700. For copies of this document call: CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 0 2002 The CNA Corporation Contents Summary . 1 Introduction . 5 Methodology . 6 The U.S. Marine Corps’ new concept for forcible entry . 9 What is the purpose of amphibious warfare? . 15 Amphibious warfare and the strategic level of war . 15 Amphibious warfare and the operational level of war . 17 Historical changes in amphibious warfare . 19 Amphibious warfare in World War II . 19 The strategic environment . 19 Operational doctrine development and refinement . 21 World War II assault and area denial tactics. 26 Amphibious warfare during the Cold War . 28 Changes to the strategic context . 29 New operational approaches to amphibious warfare . 33 Cold war assault and area denial tactics . 35 Amphibious warfare, 1983–2002 . 42 Changes in the strategic, operational, and tactical context of warfare. 42 Post-cold war amphibious tactics . 44 Conclusion . 46 Key factors in the success of OMFTS. 49 Operational pause . 49 The causes of operational pause . 49 i Overcoming enemy resistance and the supply buildup. -

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry Under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias

The Crucial Development of Heavy Cavalry under Herakleios and His Usage of Steppe Nomad Tactics Mark-Anthony Karantabias The last war between the Eastern Romans and the Sassanids was likely the most important of Late Antiquity, exhausting both sides economically and militarily, decimating the population, and lay- ing waste the land. In Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium, Walter Kaegi, concludes that the Romaioi1 under Herakleios (575-641) defeated the Sassanian forces with techniques from the section “Dealing with the Persians”2 in the Strategikon, a hand book for field commanders authored by the emperor Maurice (reigned 582-602). Although no direct challenge has been made to this claim, Trombley and Greatrex,3 while inclided to agree with Kaegi’s main thesis, find fault in Kaegi’s interpretation of the source material. The development of the katafraktos stands out as a determining factor in the course of the battles during Herakleios’ colossal counter-attack. Its reforms led to its superiority over its Persian counterpart, the clibonarios. Adoptions of steppe nomad equipment crystallized the Romaioi unit. Stratos4 and Bivar5 make this point, but do not expand their argument in order to explain the victory of the emperor over the Sassanian Empire. The turning point in its improvement seems to have taken 1 The Eastern Romans called themselves by this name. It is the Hellenized version of Romans, the Byzantine label attributed to the surviving East Roman Empire is artificial and is a creation of modern historians. Thus, it is more appropriate to label them by the original version or the Anglicized version of it. -

Department of Defence (PDF 1287KB)

Submission No 20 Inquiry into Australia’s relationship with India as an emerging world power Organisation: Department of Defence Address: Russell Offices Canberra ACT 2600 Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Foreign Affairs Sub-Committee MINISTER FOR DEFENCE THE HON DR BRENDAN NELSON MP Senator Alan Ferguson Chair t18 JKiJ Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear SepCAQCA~~Ferguson Thank you for your lefter of 31 March 2006 regarding the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Inquiry into Australia ‘s relationsIU~ with India as an emerging world power I am pleased to enclose for you, the Defence submission on the Australia — India defence relationship. The subject ofAustralia’s relationship with India is obviously important to Australia’s strategic and national interests, and I look forward to seeing the results ofyour Committee’s inquiry. I trust you will find the Defence submission of interest to the Inquiry. Yours sincerely Brendan Nelson End Parliament House, Canberra ACT 2600 Tel: (02) 6277 7800 Fax: (02)62734118 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE SUBMISSION Arntr4iau Govvnnncnt JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, DEFENCE AND TRADE INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA’S RELATIONSHIP WITH INDIA AS AN EMERGING WORLD POWER DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE SUBMISSION JOINT STANDING COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS, DEFENCE AND TRADE INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA’S RELATIONSHIP WITH INDIA AS AN EMERGING WORLD POWER Page Executive Summary 3 Introduction 4 Policy Basis for theAustralia — India defence relationship 4 India ‘s strategic outlook and military modernisation 5 Defence engagement between Australia and India 6 Outlookfor the Australia — India defence relationship 8 Annexes: A. -

Barry Strauss

Faith for the Fight BARRY STRAUSS At a recent academic conference on an- cient history and modern politics, a copy of Robert D. Ka- plan’s Warrior Politics was held up by a speaker as an example of the current influence of the classics on Washing- ton policymakers, as if the horseman shown on the cover was riding straight from the Library of Congress to the Capitol.* One of the attendees was unimpressed. He de- nounced Kaplan as a pseudo-intellectual who does more harm than good. But not so fast: it is possible to be skeptical of the first claim without accepting the second. Yes, our politicians may quote Kaplan more than they actually read him, but if they do indeed study what he has to say, then they will be that much the better for it. Kaplan is not a scholar, as he admits, but there is nothing “pseudo” about his wise and pithy book. Kaplan is a journalist with long experience of living in and writing about the parts of the world that have exploded in recent decades: such places as Bosnia, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Russia, Iran, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan. Anyone who has made it through those trouble spots is more than up to the rigors of reading about the Peloponnesian War, even if he doesn’t do so in Attic Greek. A harsh critic might complain about Warrior Politics’ lack of a rigorous analytical thread, but not about the absence of a strong central thesis. Kaplan is clear about his main point: we will face our current foreign policy crises better by going *Robert D. -

1 Civil-Military Relations in India the Soldier and the Mantri1 by Vice

This article is forthcoming in the November 2012 issue of Defence and Security Alerts. All rights reserved. No part of this article may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the author, except in the case of a reviewer, who may quote brief passages embodied in critical articles or in a review. Author’s email: [email protected] Civil-Military Relations in India The Soldier and the Mantri1 by Vice Admiral (Retd.) Vijay Shankar The Curzon-Kitchener Imbroglio Between April 1904 and August 1905, an intriguing incident occurred in the governance of the Raj, the tremors of which are felt to this day. The then Viceroy Lord Curzon, emphasizing the need for dual control of the Army of India, deposed before the Secretary of State, at Whitehall, imputing that the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Kitchener was “subverting the military authority of the Government of India” (almost as if) “to substitute it with a military autocracy in the person of the Commander-in-Chief.” This was in response to Kitchener having bypassed the Viceroy and placing a minute before the home Government where he described the Army system in India, as being productive of “enormous delay and endless discussion, while the military member of the (Viceroy’s Executive) Council rather than the Commander-in-Chief, was really omnipotent in military matters.” He further remarked that “no needed reform can be initiated and no useful measure be adopted without being subjected to vexatious and, for the most part, unnecessary criticism, not merely as regards the financial effect of the proposal but as to its desirability or necessity from a purely military point of view.” 2 In the event, both Viceroy Curzon and the Military Member of his Council, Sir Elles, on receipt of the Imperial Government’s direction subordinating the Military Member to the Commander-in- Chief, resigned. -

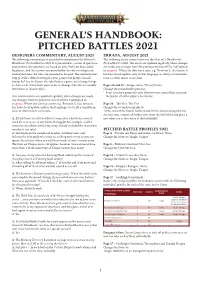

General's Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021

® GENERAL’S HANDBOOK: PITCHED BATTLES 2021 DESIGNERS COMMENTARY, AUGUST 2021 ERRATA, AUGUST 2021 The following commentary is intended to complement the General’s The following errata correct errors in the General’s Handboook: Handbook: Pitched Battles 2021. It is presented as a series of questions Pitched Battles 2021. The errata are updated regularly; when changes and answers; the questions are based on ones that have been asked are made, any changes from the previous version will be highlighted by players, and the answers are provided by the rules writing team in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it and explain how the rules are intended to be used. The commentaries has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation help provide a default setting for your games, but players should issue or other minor correction. always feel free to discuss the rules before a game, and change things as they see fit if they both want to do so (changes like this are usually Pages 24 and 25 – Savage Gains, Victory Points referred to as ‘house rules’). Change the second bullet point to: ‘- Score 2 victory points for each objective you control that is not on Our commentaries are updated regularly; when changes are made, the border of either player’s territories.’ any changes from the previous version will be highlighted in magenta. Where the date has a note, e.g. ‘Revision 2’, this means it Page 36 – The Vice, The Vice has had a local update, only in that language, to clarify a translation Change the second paragraph to: issue or other minor correction. -

The Death of the Knight

Academic Forum 21 2003-04 The Death of the Knight: Changes in Military Weaponry during the Tudor Period David Schwope, Graduate Assistant, Department of English and Foreign Languages Abstract The Tudor period was a time of great change; not only was the Renaissance a time of new philosophy, literature, and art, but it was a time of technological innovation as well. Henry VII took the throne of England in typical medieval style at Bosworth Field: mounted knights in chivalric combat, much like those depicted in Malory’s just published Le Morte D’Arthur. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, warfare had become dominated by muskets and cannons. This shift in war tactics was the result of great movements towards the use of projectile weapons, including the longbow, crossbow, and early firearms. Firearms developed in intermittent bursts; each new innovation rendered the previous class of firearm obsolete. The medieval knight was unable to compete with the new technology, and in the course of a century faded into obsolescence, only to live in the hearts, minds, and literature of the people. 131 Academic Forum 21 2003-04 In the history of warfare and other man-vs.-man conflicts, often it has been as much the weaponry of the combatants as the number and tactics of the opposing sides that determined the victor, and in some cases few defeated many solely because of their battlefield armaments. Ages of history are named after technological developments: the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Our military machine today is comprised of multi-million dollar airplanes that drop million dollar smart bombs and tanks that blast holes in buildings and other tanks with depleted uranium projectiles, but the heart of every modern military force is the individual infantryman with his individual weapon. -

SOUTH ASIA Post-Crisis Brief

SOUTH ASIA Post-Crisis Brief June 2019 Table of Contents Contributors II Introduction IV Balakot: The Strike Across the Line 1 Vice Admiral (ret.) Vijay Shankar India-Pakistan Conflict 4 General (ret.) Jehangir Karamat Lessons from the Indo-Pak Crisis Triggered by Pulwama 6 Manpreet Sethi Understanding De-escalation after Balakot Strikes 9 Sadia Tasleem Signaling and Catalysis in Future Nuclear Crises in 12 South Asia: Two Questions after the Balakot Episode Toby Dalton Pulwama and its Aftermath: Four Observations 15 Vipin Narang The Way Forward 19 I Contributors Vice Admiral (ret.) Vijay Shankar is a member of the Nuclear Crisis Group. He retired from the Indian Navy in September 2009 after nearly 40 years in service where he held the positions of Commander in Chief of the Andaman & Nicobar Command, Commander in Chief of the Strategic Forces Command and Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet. His operational experience is backed by active service during the Indo-Pak war of 1971, Operation PAWAN and as chief of staff, Southern Naval Command during Operation ‘VIJAY.’ His afloat Commands include command of INS Pa- naji, Himgiri, Ganga and the Aircraft Carrier Viraat. He is the recipient of two Presidential awards. General (ret.) Jehangir Karamat is a retired Pakistani military officer and diplomat and member of the Nuclear Crisis Group. He served in combat in the 1965 and 1971 India-Pakistan wars and eventually rose to the position of chairman of the Pakistani Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee before retiring from the armed forces. Karamat was the Pakistani ambassador to the United States from November 2004 to June 2006. -

To Which in Pitched Battle Every General Is Liable- Especially As Grant

132 MILITARY HISTORY OF to which in pitched battle every general is liable- especially as Grant felt assured that he could ac- complish his purpose by other means and with less loss of life, even if it took a little longer. The same strategy, even the same daring, appropriate enough in a subordinate commander in a distant theatre, would have been unseasonable and inexpedient in the general-in-chief, at the head of the principal army of the nation, and at a critical moment in the history of the state, when every check was magni- fied by disloyal opponents into irremediable disaster, and a serious defeat in the field might entail political ruin to the cause for which all his battles were fought. For, with all his willingness to take risks in cer- tain contingencies, with all his preference for aggres- sive operations, Grant was no rash or inconsiderate commander. He was able to adapt his strategy to the slow processes of a siege as well as to those imminent crises of battle when fortune hangs upon the decision of a single moment. At times audacious in design or incessant in attack, at others he was cautious, and deliberate, and re- strained; and none knew better than he when to remain immovable under negative or apparently unfavorable circumstances. At present he be- lieved the proper course in front of Petersburg to be-to steadily extend the investment towards the Southside road, while annoying and exhaust- ing the enemy by menaces and attacks at various points, preventing the possibility of Lee's detach- ing in support of either Hood or Early, and him- self waiting patiently till the moment should come to strike a blow like those he had dealt earlier in the war..